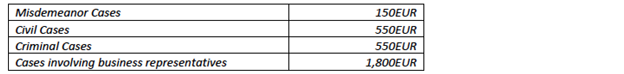

Box 14: How Much on Average Do Court Users Pay?

Average total costs as reported by court users in the Multi-Stakeholder Justice Survey 2013 including all court fees, lawyers’ fees, and travel costs, but not including fines.

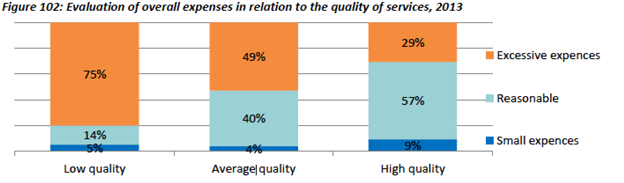

Box 15: Costs vs. Quality – An Insight into Court Users’ Perceived Willingness to Pay

Whilst court users complain about the costs of going to court, they are far more willing to pay if they are satisfied with the quality of justice services delivered. As shown in Figure 98, 75 percent of court users who report that the quality of services they received was low also reported that the costs were excessive. By contrast, the 29 percent of court users who reported that quality was high considered the costs to be excessive.

The above results lead to the conclusion that improvements in quality would increase not only user satisfaction but also access to justice. These results highlight the interaction between efficiency, quality and access. Users who experience a lengthy time to resolution are likely to have paid more and be less satisfied with the service. By contrast, users who receive a prompt high-quality service are more likely to be satisfied and to perceive value in that service.

‘(...) I can’t do my job and do this [pursue the case in court] at the same time, so I lose money. That’s why it’s very expensive, really time consuming and burdening.’505

‘As had been the case during the 2007 visit, several detained persons who had benefited from the services of ex-officio lawyers complained about the quality of their work; in particular, the ex- officio lawyers apparently met their clients only once (in court), and often tried to convince them to confess to the offence for which they were being charged. Once again, the delegation heard allegations that the choice of a particular lawyer had been imposed on the persons concerned by the police.’ 534