Serbia Justice Functional Review

External Performance Assessment > Quality of Justice Services Delivered

f. Effectiveness of the Appeal System in Ensuring Quality of Decision-Making

- Although appeals are an important mechanism for accountability and control,379 system-wide data on appeal and reversal rates can indicate poor quality in decision-making.380 Appeals also relate to efficiency, as appeals prolong the overall duration of a case and increase caseloads.381 In general terms, a steady and high-performing judiciary is likely to have low appeal rates and high rates of reversal of decisions gravitating around 50 percent,382 and decisions to reverse comprise a combination of amended decisions and remanded decisions.

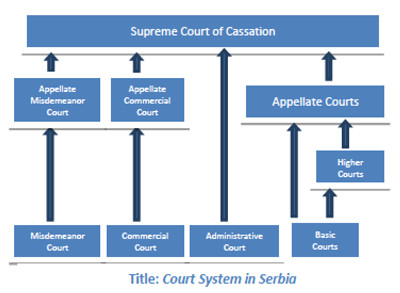

- This section analyses available appeals data through three dimensions: appeals by court type and case type, and then appeals by location, corresponding to Indicator 2.5 of the Performance Framework. The section then analyzes the possible reasons that drive up appeals and options to improve the appeal environment.

Making assessments about appeals is a delicate area of performance measurement in

Serbia. While this is an important indicator monitored for Chapter 23, it is also an area on

which stakeholders expressed strong and varying views. Several stakeholders report that the biggest problem in Serbia’s judiciary is its ‘appeals problem’. Yet (or perhaps because of this), hard data within the system are difficult to track.

Making assessments about appeals is a delicate area of performance measurement in

Serbia. While this is an important indicator monitored for Chapter 23, it is also an area on

which stakeholders expressed strong and varying views. Several stakeholders report that the biggest problem in Serbia’s judiciary is its ‘appeals problem’. Yet (or perhaps because of this), hard data within the system are difficult to track.

- Appeals data are particularly fragmented within the system, and the issue of appeals highlights all the weaknesses of existing case management approaches, including inflation and duplication of case numbers, fragmentation and lack of electronic exchange between ICT systems and lack of coordination between courts. The Review team was required to undertake detailed and very time-consuming data processing and analysis in cooperation with several judges to develop this section, suggesting that such data are not routinely analyzed.383 It is essential that the system improve data collection and analysis in this important field.

i. Appeals by Court Type and Case Type

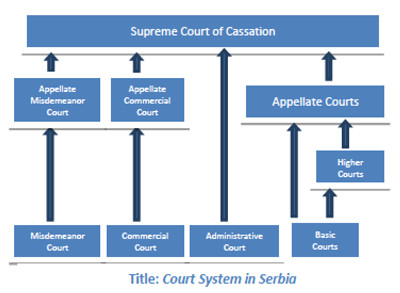

- As expected, the Higher Courts and Appellate Courts receive the most appeals, and some types of cases are more likely to be appealed than others. The following analysis tracks appeals by court type, and then offers some views on reasons for the perceived ‘appeals problem’ in Serbia.

a. Appeals from Basic Court Decisions

- Precise data on lodged appeals from the Basic Courts to the Higher Courts and Appellate Courts are not available.384 The Review team has carefully estimated the number of appeals lodged from Basic court decisions, which required significant data processing and consultations with relevant stakeholders.385

- Most appeals from the Basic Court go directly to the Appellate Court for review (big appellation), while some go to the Higher Court for review (small appellation). It is estimated that appeals against Basic Court decisions comprise around 90 percent of the Appellate Court’s inflow.386

- Appeals against Basic Court decisions in civil litigious cases are high, with an appeal rate of around 22.84 percent.387 Most of the appeals pertain to ‘P’ (civil litigation) and ‘P1’ (labor law disputes) case codes, where the appeal rate against merit decisions is estimated to be around 45 percent.

- Appeals rates against Basic Court decisions in criminal matters are also high at 23 percent.388 Of appeal decisions made in 2013, around 66.42 percent were confirmed, 19.66 percent were remanded to the lower court, 12.05 percent were amended, and 1.85 percent were partially amended. Criminal cases for which the maximum penalty is 10 years appear to be more likely to be appealed, with an estimated appeal rate of 36 percent.389

- Appeals against civil non-litigious cases appear to be very low, with an appeal rate of around 1 percent.390 This is due to fact that non-litigious cases do not involve a dispute between the parties, so unfavorable decisions by the court are less likely to happen. Also, not all non-litigious decisions of the Basic Courts can be appealed, so the number is somewhat deflated.

- Appeals against enforcement decisions are also very low.391 Out of this number. 69.56 percent were confirmed, 36.2 percent were remanded to the lower court, 2.5 percent were amended, and 0.7 percent were partially amended. An additional 28,733392 decided cases should also be included in the analysis on enforcement appeals as this number represents cases in which a panel of three judges decides on objections on certain procedural decisions in enforcement proceedings.

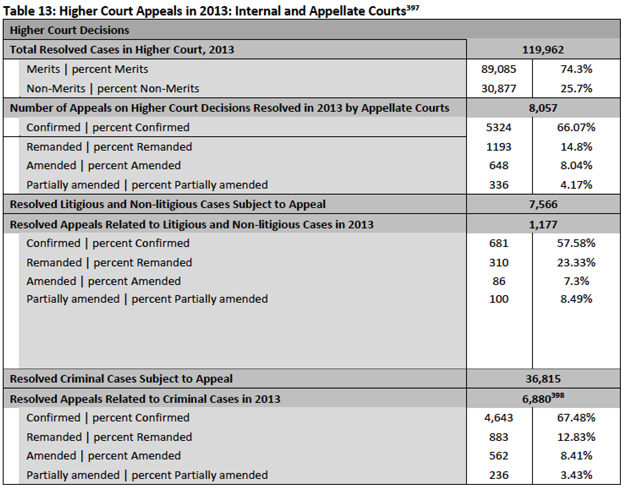

b. Appeals from Higher Court Decisions to the Appellate Court

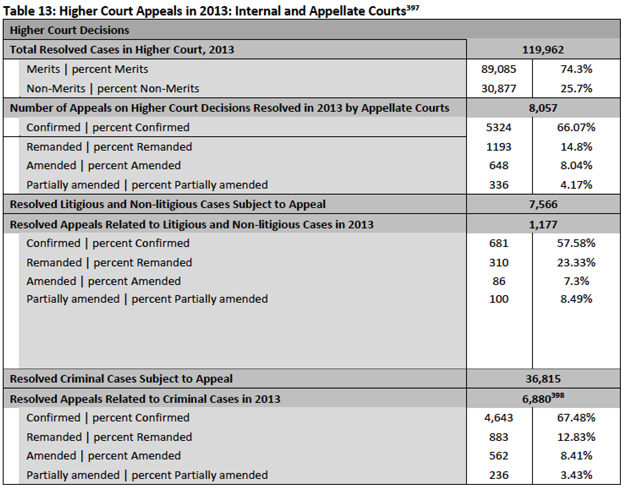

- The appeal rate from Higher to Appellate Courts is relatively low and the remand rate is moderate. In 2013, of the 44,381 civil and criminal related decisions made by the Higher Courts, an estimated 8,300 cases were appealed to the Appellate Courts394 representing around 8.8 percent of those decisions. Of the appeals decided in 2013, 66.07 percent were confirmed, 14.08 percent were remanded to the lower court, 8.04 percent were amended, and 4.17 percent were partially amended.

- Of the High Court decisions that are appealed, most relate to criminal matters. Civil cases are estimated to comprise only around 15.5 percent of the caseload.395 Of civil appeals resolved in 2013, 57.58 percent appeals were confirmed, 23.33 percent were remanded to the lower court, 7.3 percent were amended, and 8.49 percent were partially amended. Certain criminal cases are much more likely to be appealed, particularly in the ‘K’ case category, where approximately 65.62 percent of decisions get appealed. Other criminal cases do not show such a high percentage of appealed decisions and are more similar to civil cases with an appeal rate of approximately 18.68 percent.396 Of appeals cases resolved, 67.48 percent were confirmed, 12.83 percent were remanded to the lower court, 8.41 percent were amended and 3.43 percent were partially amended.

- A large number of these appeals appear to lack merit. In civil litigation cases, 57.58 percent of appeals are rejected, and in criminal cases 67.48 percent. This may suggest that appeals are being pursued for instrumental purposes, for example to prolong the enforcement of the decision (see below).

- Existing statistical reporting formats published by the Supreme Court of Cassation do not show the number of appeals lodged. Instead, they show the number of decided appeals in the reporting period, and the outcomes of these decisions (confirmed, remanded, amended and partially amended). Furthermore, these statistics include decisions related to appeals lodged not only in the reporting period, but two or three years prior as well. Additionally, the Appellate Court statistics do not make distinctions between cases received from Basic Courts and cases received from Higher Courts.

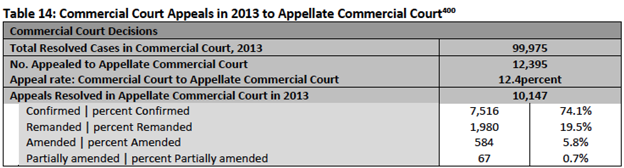

c. Appeals of Commercial Court Decisions

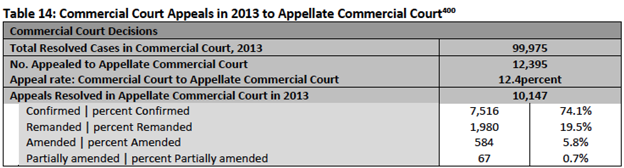

- In the commercial jurisdiction, appeal rates are moderate and remand rates are also moderate. In 2013, of the total of 99,975 Commercial Courts decisions made, 12,395 were appealed to the Appellate Commercial Courts, representing around 12.4 percent of the Commercial Court’s decisions for that year.399 Of the 10,147 appeals decisions made by the Appellate Commercial Court in 2013, 74.1 percent were confirmed, 19.51 percent were remanded to the lower court, 5.76 percent were amended, and 0.66 percent were partially amended. Again, the low rate of amended and partially amended decisions is some cause for concern.

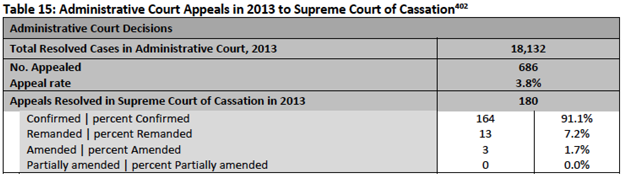

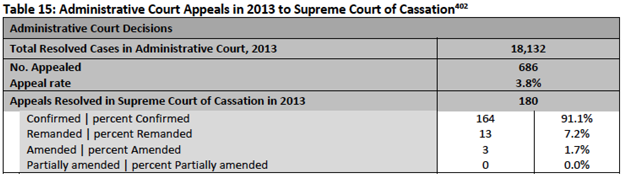

- In the administrative jurisdiction, appeal and remand rates are low. In 2013, 686 Administrative Court decisions were appealed to the SCC representing approximately 3.8 percent of all Administrative Court decisions for that year. Of the 180 administrative appeals decided by the SCC in 2013, 91.11 percent of the decisions were confirmed.401 This suggests that there is a higher level of uniformity and consistency in the administrative law field than in other fields in Serbia. It may also suggest that a large number of appeals are lodged without merit, for example by institutions with overly-zealous appeal policies.

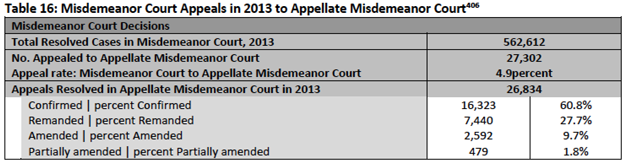

e. Appeals of Misdemeanor Court Decisions

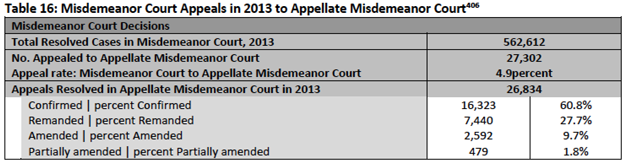

- In the misdemeanor jurisdiction, appeal rates are low and remand rates fairly high. In 2013, 27,302 decisions of the Misdemeanor Court were appealed to the Appellate Misdemeanor Court, representing approximately 4.9 percent of all of the Misdemeanor Courts’ decisions rendered for that year. At the Appellate Misdemeanor Court, 26,834 appeals were resolved.403 Of them, 60.83 percent were confirmed, 9.66 percent were amended, 27.73 percent were remanded to the lower court, and 1.79 percent were partially amended. The percentage rates are roughly comparable to the 2012 data 404 (see Table 16 below).

- The appeals data are unsurprising, and likely reflect a balanced performance in the Misdemeanor and Appellate Misdemeanor Courts.405 However, one surprising finding is the low amendment rate. In only approximately 10.5 percent of cases, the Appellate Misdemeanor Court replaced the first instance decision with its own. Misdemeanor cases should be relatively straightforward, so the Appellate Misdemeanor Court would be well placed to amend the decision and save the parties and the Misdemeanor Courts the necessity of a retrial. Reasons for this low amendment rate should be further explored, and options developed to equip the Appellate Misdemeanor Courts better to amend decisions.

ii. Appeals by Location

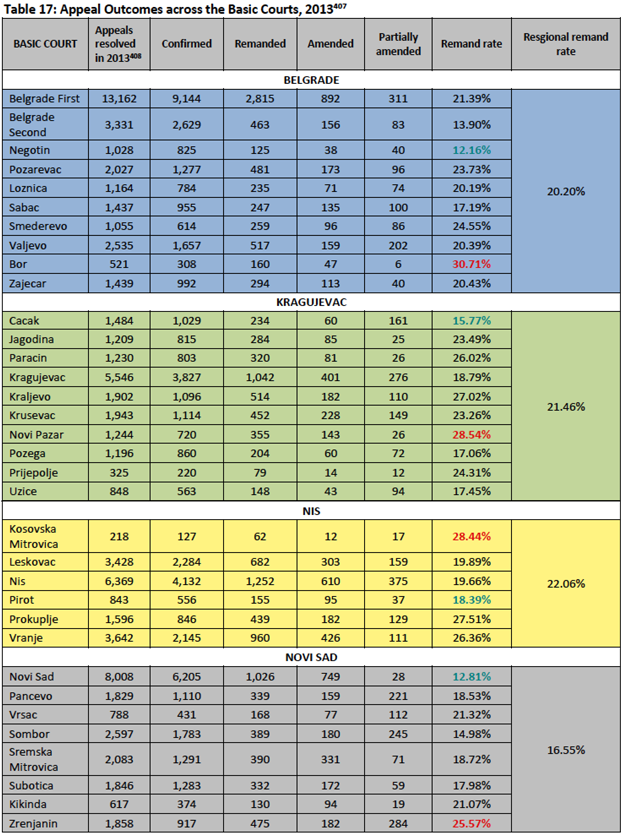

- The Review analyzed variations in appeal rates across the various Basic and Higher Courts. Significant variation in appeals data can indicate a lack of uniformity in the application of the law across the territory.

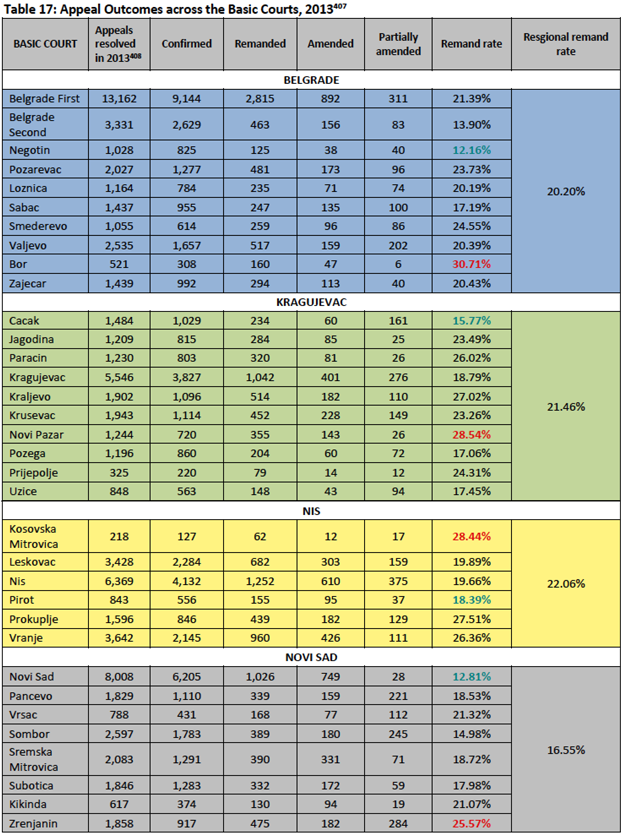

- Outcomes of appeal vary across the Basic Courts. In the Novi Sad appellate region for example, Basic Court decisions are remanded back to the Basic Court in around 16.5 percent of appeals, whereas in Nis nearly 50 percent are more often remanded back to the court in around 22 percent of appeals. Within regions, appeals from Higher Courts vary. Basic Court decisions in Negotin are remanded back to the court in 12 percent of appeals, but down the road in Bor, they are remanded back to the court in 30.71 percent of appeals. Basic Court decisions in Cacak are remanded back to the court in 15.7 percent of appeals, whereas in Novi Pazar they are remanded back to the court in 28.5 percent of appeals. Basic Court decisions in Novi Sad are remanded back to the court in as few as 12.8 percent of appeals, whereas in Zrenjanin decisions are remanded back to the court twice as often, in 25.6 percent of appeals. In Table 17 below, the Basic Court with the highest percentage of remanded back to the court decisions is marked in red, while the court with the lowest number of appeal decisions is marked in green.

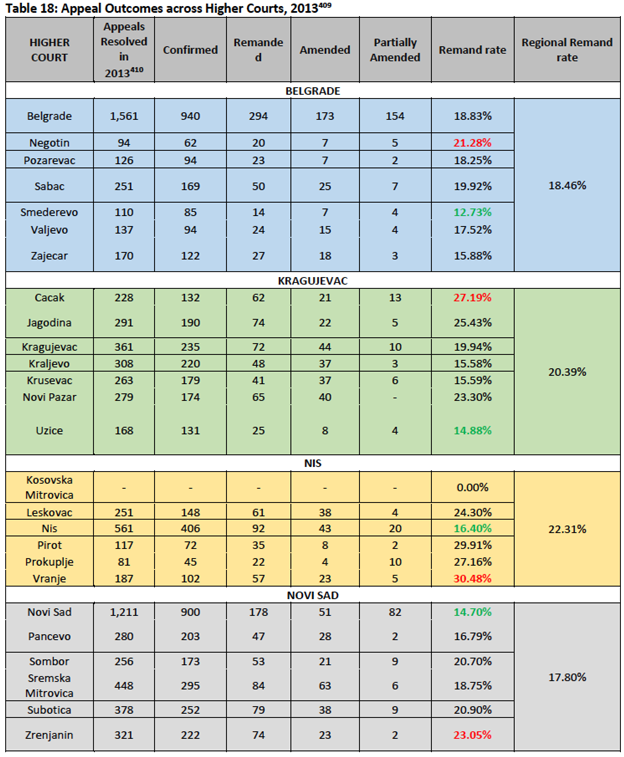

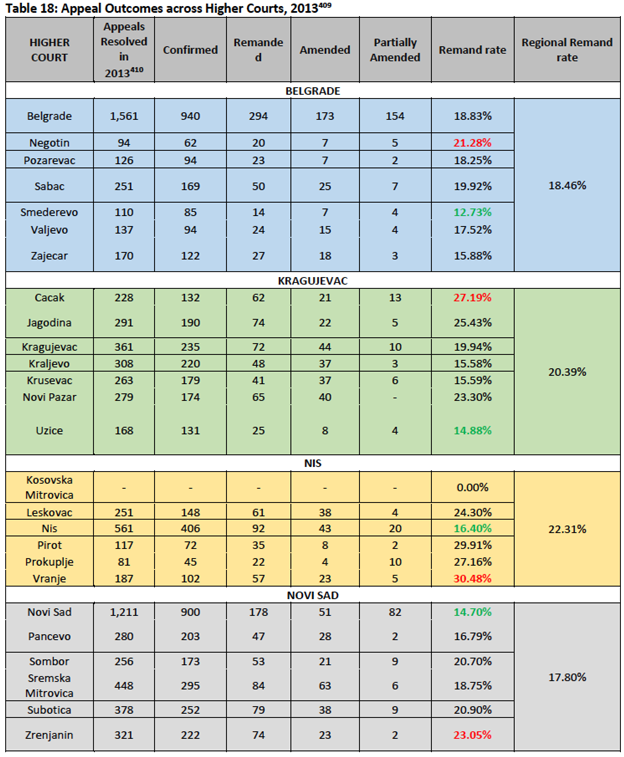

- Outcomes on appeal also vary across the Higher Courts. Remand rates are fairly consistent across the appellate regions, ranging from 17.8 to 22.3 percent. However, appeals within regions vary more widely. Higher Court decisions in Smederevo are remanded back to the court in 12.7 percent of appeals, but in Negotin they are remanded back to the court in 21.31 percent of appeals. Higher Court decisions in Uzice are remanded back to the court in 14.9 percent of appeals, whereas in Cacak they are remanded back to the court nearly twice as often, in 27.2 percent of appeals. Higher Court decisions in Nis are remanded back to the court in as few as 16.4 percent of appeals, whereas in Vranje decisions are remanded back to the court nearly twice as often in 30.5 percent of appeals. Higher Court decisions in Novi Sad are remanded back to the court in as few as 14.7 percent of appeals, whereas down the road in Zrenjanin, decisions are remanded back to the court in 27.1 percent of appeals.

iii. User Perceptions of Appeals

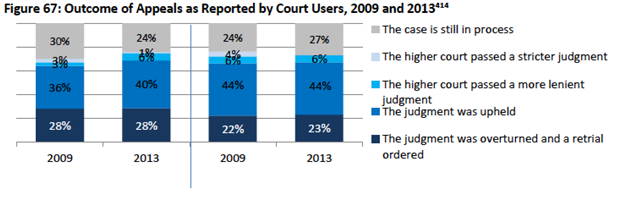

- The Multi-Stakeholder Justice Survey provides some additional insights to the statistical data outlined above.411 According to survey data, around one-third of court proceedings with the public, in which first instance judgment was rendered between January 2011 and November 2013, were appealed.412 For the business community, 38 percent were appealed. In comparison with cases in which first instance judgment was rendered in the period starting January 2007 up to the end of 2009, the percentage of appeals involving the public decreased by 3 percent. By contrast, the percentage of appeals involving the business community increased by 5 percent.

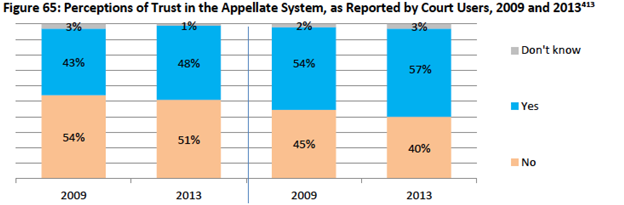

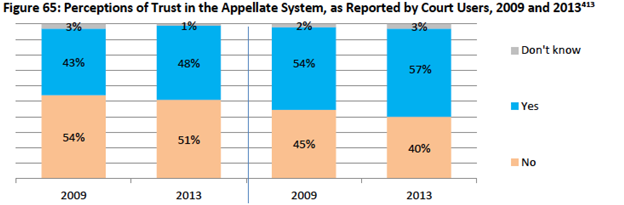

- Trust in the appellate system among court users is low. In 2013, less than half (48 percent) of the public with recent experience in court cases stated that they trust the appellate system. Meanwhile, a slightly higher 57 percent of business sector representatives with court case experience stated that they trust the appellate system. What remains unclear from these perceptions is whether this lack of trust either encourages or discourages court users to lodge appeals.

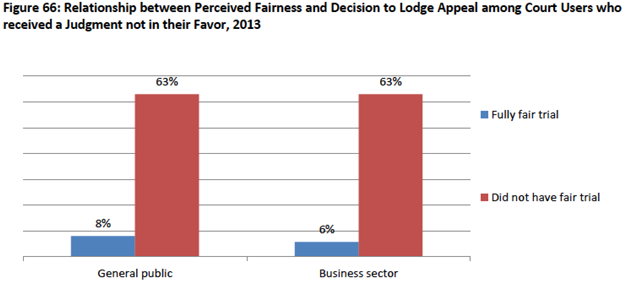

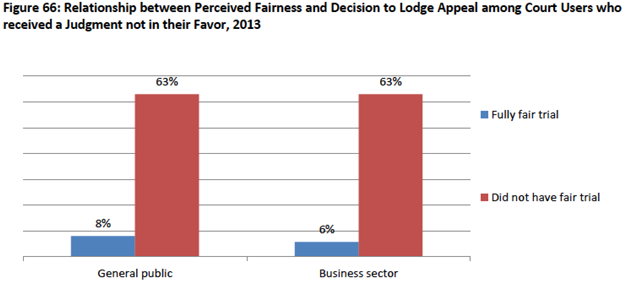

- The decision of a party to file an appeal related strongly to that party’s perception of the fairness of the first-instance trial. Court users who received a judgment that was not in their favor were on average 10 times more likely to file an appeal if they considered the decision to be not fully fair. In contrast, court users who received a judgment that was not in their favor but who considered the decision to be fair appealed in only 8 percent of cases for general court users and 6 percent of cases for business users.

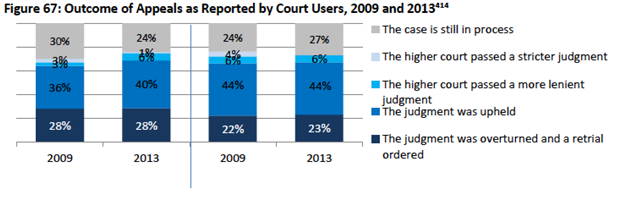

- In most cases, court users reported that the second-instance court upheld the judgment. However, in 28 percent of cases with the public the judgment was overturned and a retrial was ordered. In 22 percent of cases with the business sector the judgment was overturned and a retrial was ordered (Figure 67). In very few cases did the Appellate Court amend the lower court’s decision.

- When a retrial is ordered, in most of the cases court users reported that a retrial occurs only once. This was the case for over 70 percent of retried cases with the public, and over 60 percent of retried cases with business sector. However, a retrial was ordered twice in 12 percent of cases with the public and 22 percent of cases with business sector. Re-trials were ordered three or more times in around 10 percent of the cases, although it is not clear whether these are successive appeals on the same or different issues.

- Fortunately, recent procedural reforms limited the possibility of successive retrials. Under new criminal and civil procedural laws, and after the second appeal, the appellate court is obliged to replace the lower court’s judgment with its own. Over time, this should reduce the overall number of appeals in the system and limit this ‘ping-pong’ effect, which causes much frustration for practitioners and court users. As a result, the figures above are unlikely to be replicated in the future416 (see Figure 68).

iv. Factors Explaining High Appeal Rates and High Variation in Appeals

- High appeal rates suggest a range of problems. Overwhelmingly, the issue is likely to be perceived lack of uniformity in the law among, which encourages parties to appeal. However, there are additional factors.

- Some suggest that appeal rates are high because the court fees for lodging appeals are low, creating little disincentive for litigants to ‘throw the dice’ and lodge an appeal without merit. However, the data do not strongly support this theory. A party’s decision to lodge an appeal is likely also to consider lawyer’s fees, which represent a large portion of the overall cost of legal action and are higher on appeal. Further, if it were true, one would expect to see higher appeal rates in misdemeanor cases and for criminal cases than civil cases because the fees for lodging criminal appeals are significantly lower.417 The figures show that when criminal appeals are lodged, it is more likely to be at the request of the Prosecutor than the defendant, likely due to prosecutorial appeal policies.

- Lawyers may play a hand in driving up appeal rates. In the Multi-Stakeholder Justice Survey, unrepresented litigants were far less likely to appeal their cases. Attorneys have a financial incentive to draw out their clients’ case, 418 and can also advise on the likelihood of success on appeal and the tactical advantages of appeals, including delays in enforcement.419 Ex-officio attorneys appointed by the state are reported to do so more than private attorneys, perhaps because their work goes largely unmonitored. Some parties (and their attorneys) may be pursuing frivolous or vexatious appeals for instrumental purposes (i.e. to harass the other party or to prolong the inevitable final judgment.420

- Some suggest that appeal rates are high because of cultural reasons, but again the data do not support this. Had there been a general Serbian cultural preference to use the court (and its appeal process) as an instrument of retribution, one would expect high appeal rates across all cases, including for example in misdemeanor cases.421

- Looking forward, appeals in criminal cases will likely continue and may rise with the introduction of the new CPC. Stakeholders report confusion regarding the application of the law in adversarial proceedings, creating fertile ground for criminal appeals. Appeals against sentences, which are more common than appeals against conviction, will not abate without other mechanisms that provide greater consistency in sentencing.422

- Yet the low remand rate on appeal suggests that appeals do not often ‘pay off’ for the appellant. In civil litigious cases, the 67.9 percent of the 51,140 civil litigious second instance decisions made in 2013 by the Higher and Appellate were confirmed,423 18.8 percent were remanded to the lower court, 6.8 percent were amended, and 6.5 percent were partially amended.

- Of particular concern across Serbia is the reluctance of appellate courts to replace the lower instance decision with their own. In only a small percentage of cases are higher instance courts amending the decisions of lower courts. One would expect in smaller cases that the appellate judges could, in the interests of justice and in compliance with the law, save the parties the trouble of re-litigating the matter back in the lower instance court. Doing so would also assist other judges and courts, and over time would increase uniformity in the law’s application.

- Several reasons may explain the reluctance of appellate judges to replace decisions with their own. One explanation is that appellate judges are highly driven by productivity norms, which require monthly clearance targets. This creates an incentive for judges to deal with their appeals cases quickly, and it takes longer to amend the original decision than to send the case back for re-trial.424 Similarly, lower instance judges may prefer re-trials to amendments as they benefit in their productivity norms as well. Each returning ‘recycled’ case is treated as an ‘incoming case’, and judges are already familiar with the cases and can make a new decision relatively quickly by following directions given by the appeals judge.425 The decision is later counted again as a resolved case in the lower court.

- Reasons for geographic variation are also likely to be due to lack of uniformity in the application of the law across the territory. While it is true that even neighboring courts of the same jurisdiction may have a different mixes of cases, and this can affect appeals in a given year, however, the more likely explanation is that similar cases are decided differently in different locations.426 Interviews with judges, prosecutors, attorneys and other stakeholders corroborated this view, and many examples and anecdotes were provided to the Review Team where like cases are treated differently around the country. For example, stakeholders highlighted a recent instance where three Misdemeanor Courts decided similar cases relating to public officials’ failure to lodge asset declarations. The three courts each took a different approach, resulting in three different merits decisions.

- This lack of uniformity manifests in several ways. First, there is variation in the quality of first instance decisions in particular courts, which can drive up appeals and remand rates from those locations as appellate courts rectify the work of particular lower courts. Second, variation in the quality of appeal decisions, where courts exercising appellate jurisdiction have greater or lesser capacity, or are more or less lenient in their decision-making. Variations in practice and approach to case management can also play a factor – judges in Novi Sad, for example, claim their more proactive approach to case management reduces the appeal rates and reversal rates of their cases, as files are dealt with expeditiously, leaving less room for error.

- The argument that some places are simply ‘bad’ is not supported by the data. For example, Cacak’s Basic Courts had the lowest remand rate in 2013 in the Kragujevac region but its Higher Court had the highest. Similarly Negotin’s Basic Courts had the lowest remand rate in the Belgrade region but its Higher Court had the highest. In the Novi Sad region, the Novi Sad Basic and s both had the lowest remand rates in region, and the Zrenjanin Basic and Higher Court both had the highest remand rates in the region. It is also notable that the Belgrade Basic and Higher Court were well within the range, which goes against the anecdotes that Belgrade attorneys unnecessarily drive up appeals more often than attorneys in other places. Rather than resting on generalizations, the reasons for geographic variation are more likely to be nuanced. Interviews suggest that the reasons may well be related to the practices of individual courts at both first instance and appellate level, and the approach of individual Court Presidents to promoting high quality in case management and decision-making.

- Looking forward, efforts to improve consistency and uniformity in the application of the law should be a top priority.

v. Efforts to Enhance Uniformity in the Application of the Law

- Efforts are underway to improve uniformity, led by the SCC in its authority as the most authoritative court. The SCC proposed Certification Commissions, whereby panels of judges and other experts will endorse particular decisions as contributions to jurisprudence. Some concern was voiced by stakeholders that this mechanism will be insufficient to guide jurisprudence and achieve consistency because the work of the Commissions is not binding. However, it is a good start, particularly if combined with other measures. The SCC is also hosting meetings of judges to discuss procedures and issues, so the uniformity of court practice is formalized.

- To complement these efforts, more meetings of judges and heads of department should occur to review recent cases and trends. For example, some Appellate Misdemeanor Court judges hold weekly meetings to review recent cases, and they report that this practice is useful to keep abreast of legal developments. Appellate Courts are also beginning to host periodic meetings of the Basic Court Presidents and Heads of Department in their jurisdiction to discuss recent cases and reforms. These activities are low cost and can help to promote uniformity. Such efforts should be intensified and expanded.427

- Case Law and Preparatory Departments can also enhance consistency. Larger Serbian courts also have what they call Case Law Departments, managed by a judge designated by the Court President, which follow and study recent domestic and international court cases, and inform judges, judicial assistants, and trainees about the results. While those subjects interviewed for this report indicated several courts do have active case law departments, the practice is not consistently applied and there has been little collaboration between the case law departments of various courts.

- In certain substantive topic areas, Bench Books may be valuable to guide court practice. Given the recent overhaul of the new CPC, a criminal procedure Bench Book for criminal trials may improve consistency of practice and reduce the number of criminal appeals. Bench Books could be prepared by a committee of relevant stakeholders and form the basis of ongoing training.

- Other simple advancements would enhance consistency and gradually normalize the appeals system. These include: standardized judgment writing; the use of forms, checklists and templates; greater access to information about laws, procedures and cases, as well as legal research tools; public outreach and proactive rollout of new laws; and intensified continuing training for judges. These basic measures should be prioritized. See Recommendations and Next Steps. Should they be monitored over time and found insufficient, further consideration could be given to more structural reforms to unify the application of law.

Making assessments about appeals is a delicate area of performance measurement in

Serbia. While this is an important indicator monitored for Chapter 23, it is also an area on

which stakeholders expressed strong and varying views. Several stakeholders report that the biggest problem in Serbia’s judiciary is its ‘appeals problem’. Yet (or perhaps because of this), hard data within the system are difficult to track.

Making assessments about appeals is a delicate area of performance measurement in

Serbia. While this is an important indicator monitored for Chapter 23, it is also an area on

which stakeholders expressed strong and varying views. Several stakeholders report that the biggest problem in Serbia’s judiciary is its ‘appeals problem’. Yet (or perhaps because of this), hard data within the system are difficult to track.