Box 27: Managing Expenditures Proactively: An Example from Sombor

A proactive approach to managing expenses can make a difference. The Sombor courts used to pay a local mechanic 8,500 RSD for testifying as an expert witness on the condition of vehicles involved in accidents. Upon taking over the criminal investigation function from the courts, the PPOs started bearing such costs.

The Chief Prosecutor was puzzled by their magnitude and obtained comparative rates from the neighboring areas, and was able to renegotiate the mechanic’s rate down by 60 percent. The PPO reduced the costs of procedure while the mechanic retained a high volume customer.

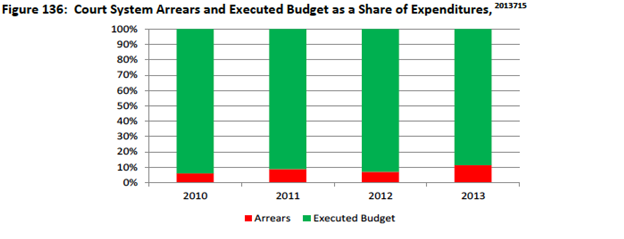

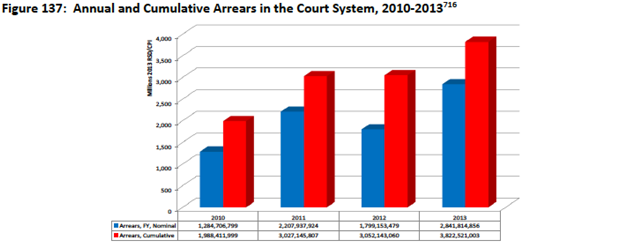

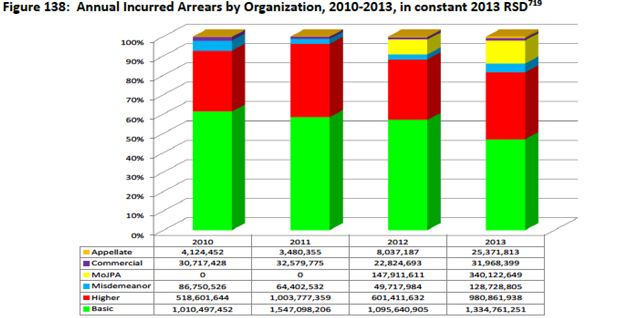

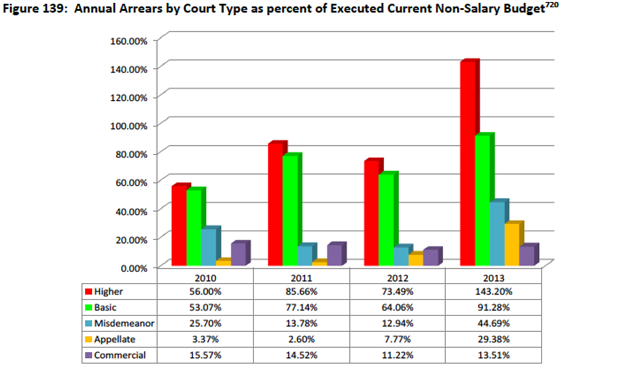

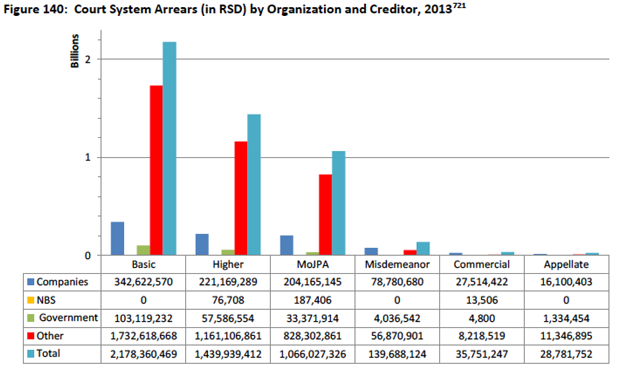

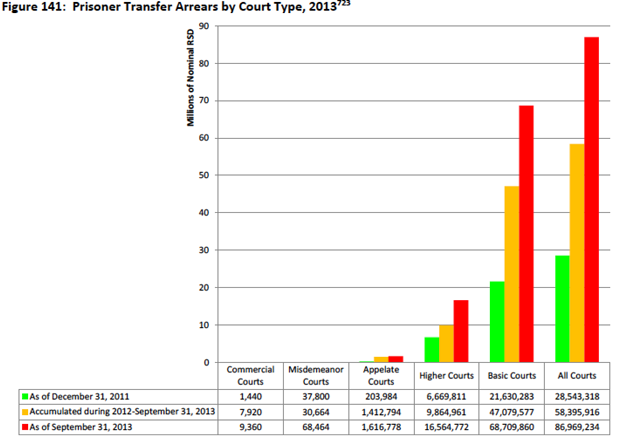

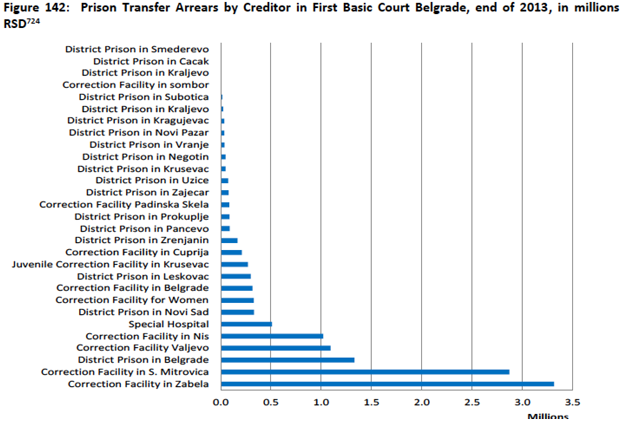

The prevalence of large arrears and corresponding enforcement judgments against courts create a

massive amount of unnecessary work. Creditors are required to pursue their claims in the court system, and the courts are required to process the cases and ironically defend them too. Staff in courts, the MOJ, the MOF and elsewhere must administer, reconcile and report on the judgments. The time of all parties involved could be better spent supporting more productive activities such as budget planning, expenditure control and reporting.