The ‘shadow workforce’ is reported to be extensive, numbering thousands, but their precise numbers and roles are unknown.

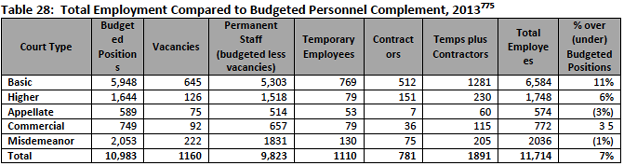

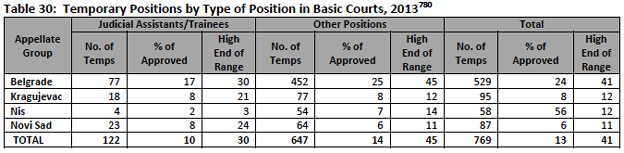

The judiciary employs over 1,100 temporary employees, representing 10 percent of the total

workforce. In some instances, they are utilized to backfill vacant

positions rather than substantively filling those positions. In other

cases however, the use of temporaries results in a total workforce

significantly exceeding the systematization. There is no effective

position control for individual courts, court types, or court levels.

However, consistent with statute, the MOJ has required that those

temporary staff exceeding 10 percent of the overall workforce be removed by June 30th, 2014.767