Courts

This chapter examines the performance of the Serbian courts for

judicial efficiency/effectiveness. The methodology used in this chapter

corresponds to the one used in 2014 Serbia Judicial Functional Review,

and data and findings of the 2014 Judicial Functional Review were used

as a baseline. Data in this chapter were collected from the SCC and

international reports, as explicitly noted in the corresponding text.

The 2020 data, collected from the SCC report, are used herein only to

demonstrate particular general trends as the effect of the Covid-19

health crisis made the year 2020 unprecedented and unfit for

year-over-year comparisons. For more information see sections

‘Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Court Efficiency’ and

'Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on PPOs Efficiency in

2020'.

Main Findings ↩︎

- From 2014 to 2019, the productivity in Serbian courts

improved in many areas, but there were still domains that needed

considerable attention. Most clearance rates were over 100

percent and the implementation of reforms that transferred most of the

enforcement cases to private bailiffs and probate cases to public

notaries. However, ‘bulk’ dispositions of enforcement cases made the

largest contributions to the favorable clearance rates; without them,

the improvements would not have been as remarkable.

- Cases delegated by one court to another inflated the

apparent number of cases nationally because these appeared in the

statistics both as cases being disposed of in the originating courts and

as cases registered in the courts receiving them. The total number of delegations

were seen in SCC’s reports, but individual court reports did not report

how many cases were delegated from or to that court.

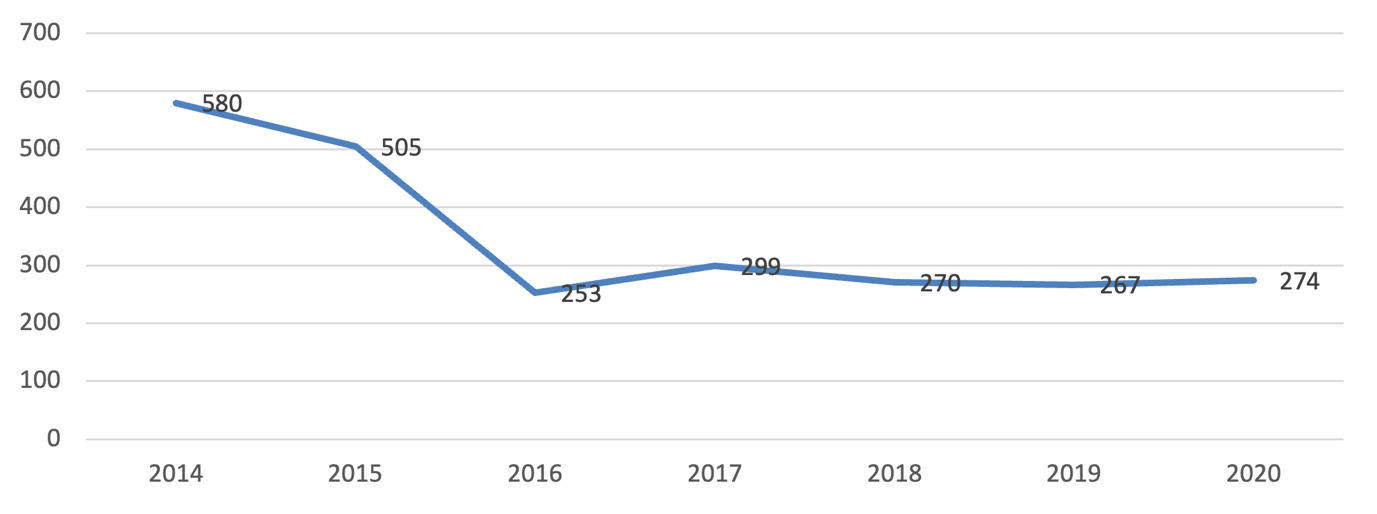

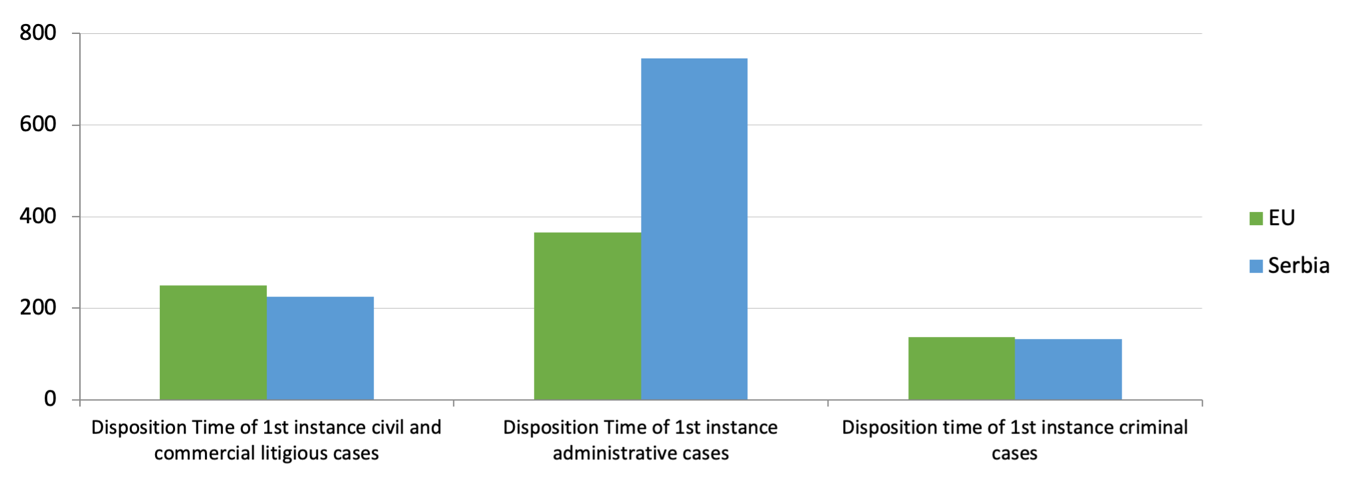

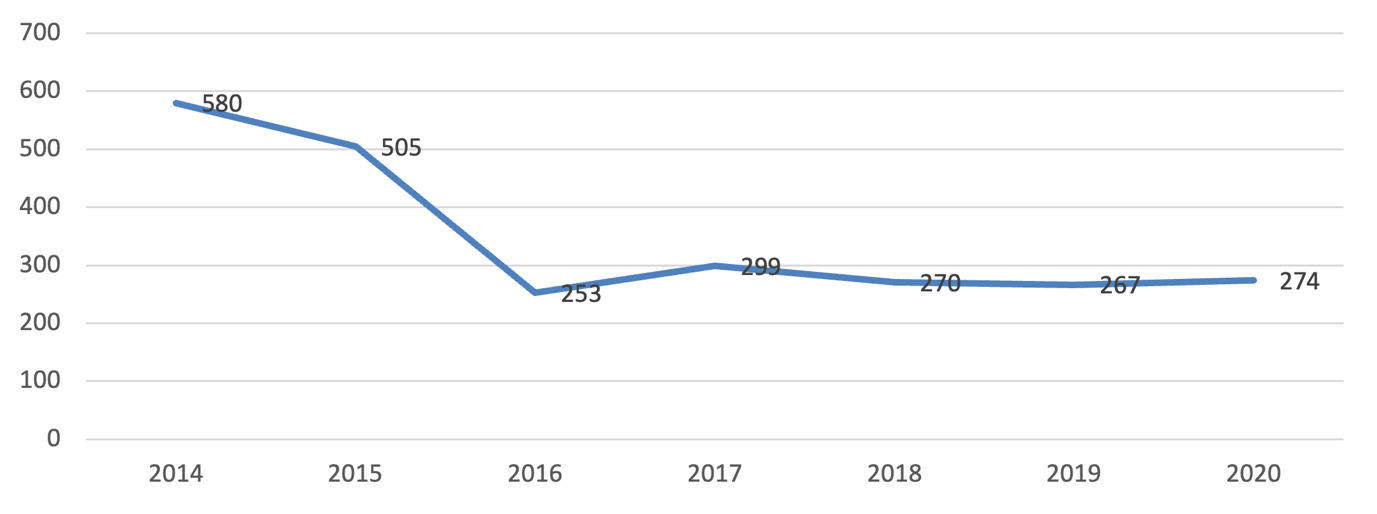

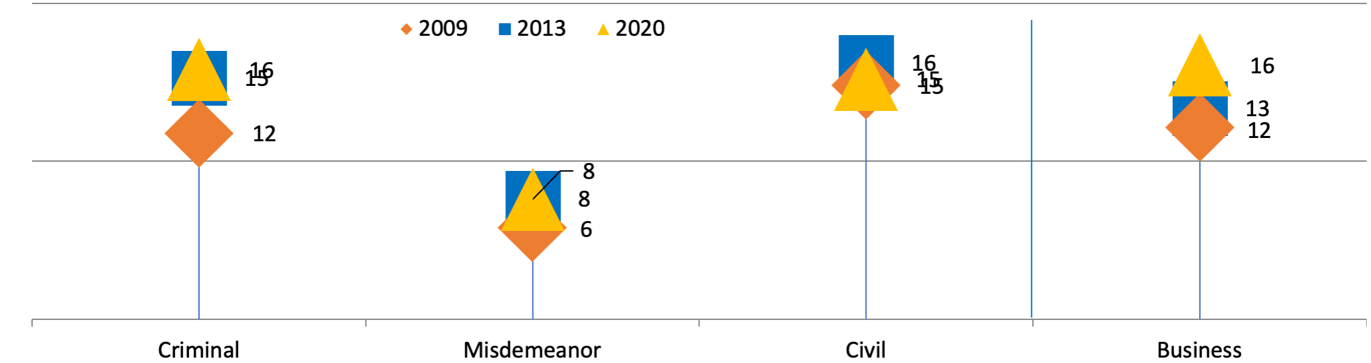

- The timeliness of case processing, measured through the

CEPEJ disposition time indicator, dramatically and continually improved

from 2014 to 2019, but with remarkable variations by case and court

type. The total disposition time for Serbian courts decreased

from 580 days in 2014 to 267 days in 2019. The total congestion ratio of

courts in Serbia improved considerably, dropping to 0.73 in 2019. The pending stock was reduced by

more than 40 percent from 2014 to 2018, or from 2,849,360 cases at the

end of 2014 to 1,656,645 cases at the end of 2019. In 2020, the total

disposition time reached 274 days, and the congestion ratio decreased

slightly to 0.75, while the courts ended the year with 1,510,472

unresolved cases.

- The National Backlog Reduction Programme that started in

2014 markedly reduced the massive backlogs in Serbian courts even if it

did not reach its stated goals.

At the outset, the goal was to reduce the backlog to 355,000 cases by

the end of 2018, from 1.7 million at the end of 2013. However, 781,000

backlogged cases were still pending at the close of 2018. The strategy

was amended in 2016 to include a goal of approximately 350,000

backlogged cases for the end of 2020, which was not met, according to

the SCC.

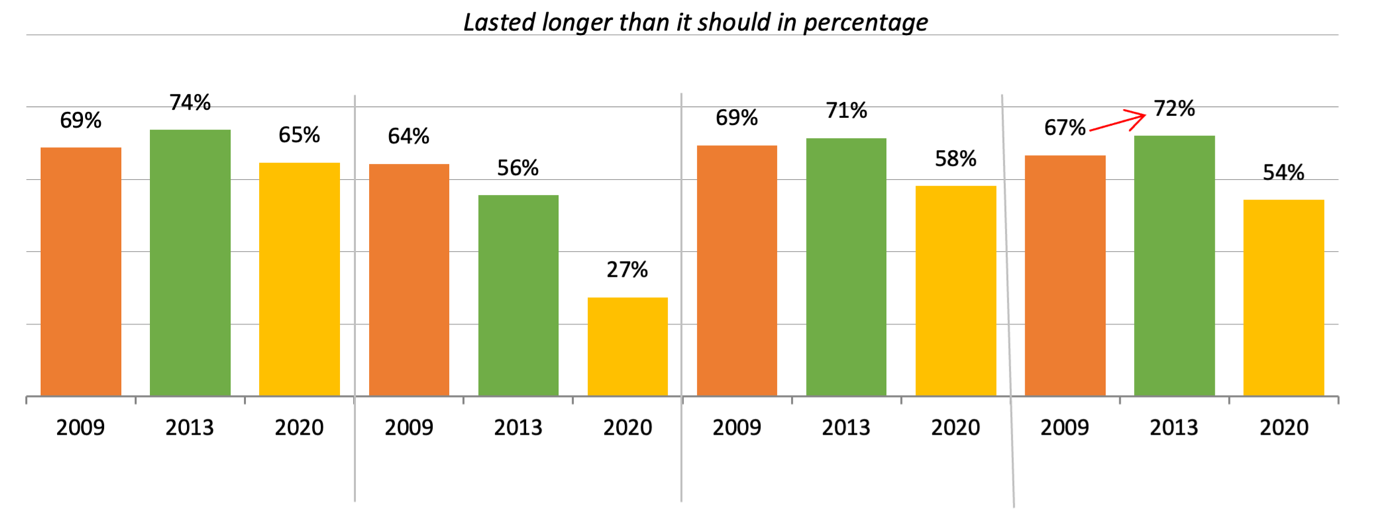

- The Law on Protection of the Right to a Trial Within

Reasonable Time may not have achieved its intended purpose.

There is no evidence the Law has shortened court proceedings, and

enforcing it requires more judicial resources to determine violations

and penalties.

- There was significant progress in reducing the courts’

backlogs of enforcement cases, but it was not clear how effective

private bailiffs had been in cases that had started as enforcement cases

in the courts. The congestion ratio of enforcement cases in

Basic Courts improved from 4.88 in 2014 to 1.47 in 2019, but many old

enforcement cases were still in the courts as of 2019, the last year for

which comparable data was available as of early 2021. The lack of

genuinely effective and timely enforcement, particularly for cases

arising in large courts, remained one of the biggest challenges for the

Serbian court system.

- The transfer of administrative tasks and probate cases to

public notaries significantly reduced the work of many judges, although

the transferred probate cases were still included in statistics about

court caseloads, workloads, and dispositions. In 2013, Basic

Courts received and resolved more than 700,000 verification cases,

compared to roughly 110,000 in 2019. Also, in 2019, 91 percent of the

134,226 newly filed probate cases were transferred to public notaries,

which was an increase of 38 percentage points from 2018. Although the

transferred probate cases were still included in court statistics,

courts had little or no work to do with them once they were

transferred.

- Except for the Administrative Court, Serbia’s clearance

rates for first-instance cases in 2018 exceeded those of EU

courts. The Administrative Court’s clearance rate for 2018 was

notably lower than in other nations, but it improved in 2019.

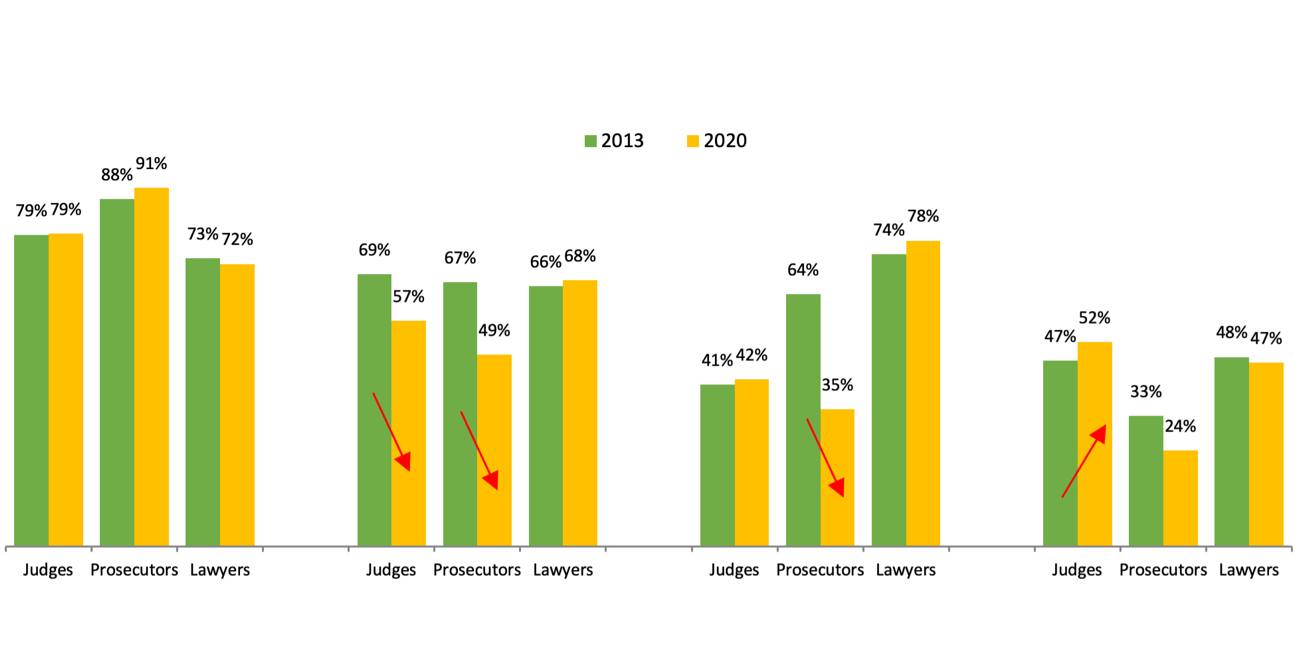

- While the number of judges on a court is a factor in the

court’s efficiency, it is not the only one. The addition of eight judges

(one-fifth of the total) in 2018 was not enough for the Administrative

Court to deal effectively with the increased number of cases and falling

dispositions that year. By contrast, the Administrative Court

increased its dispositions and clearance rate in 2019 despite losing

seven judges (and only partly due to a decrease in incoming

cases).

- Dispositions per judge displayed substantial variations

over time and between courts. The most stable dispositions per

judge were recorded in the Appellate Misdemeanor Court, while

dispositions per judge continuously increased in the Higher Courts and

the Commercial Courts. Dispositions per judge in the Administrative

Court declined sharply in 2018 and recovered in 2019.

- The practice in Serbia of evaluating judges’ productivity

based on quotas for disposition is in tension with the need to resolve

older and more complicated cases. The age structure of pending

cases indicates how courts prioritize cases for processing and whether

they are disposing of a significant number of new cases relatively

quickly, while more complicated cases are left in part of the pending

stock that may never be resolved.

- The transfer of investigative responsibilities from

courts to prosecutors was intended to improve courts’ efficiency as well

as objectivity. Because prosecutors’ offices have required some

time to implement the transfer, the short-term result has been some

delays in case disposition by courts.

- Enforcement of contracts lags behind that in other

nations.

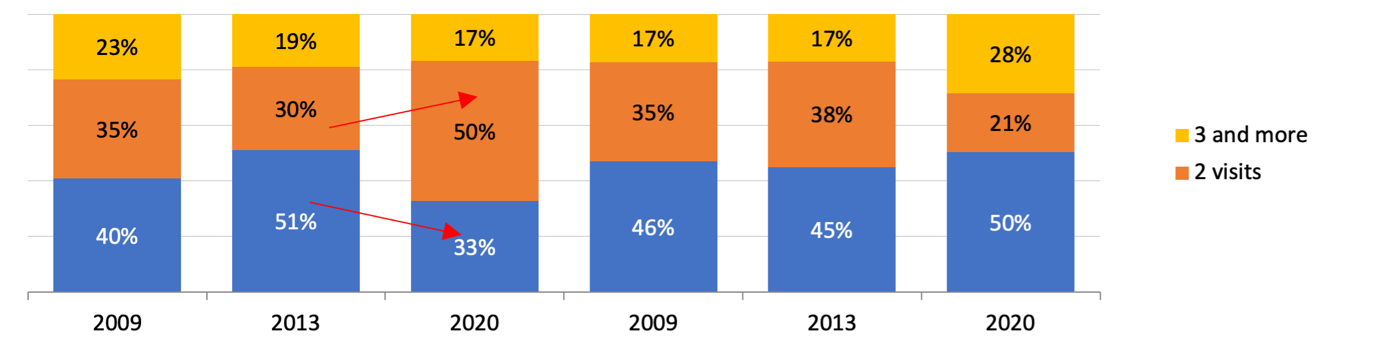

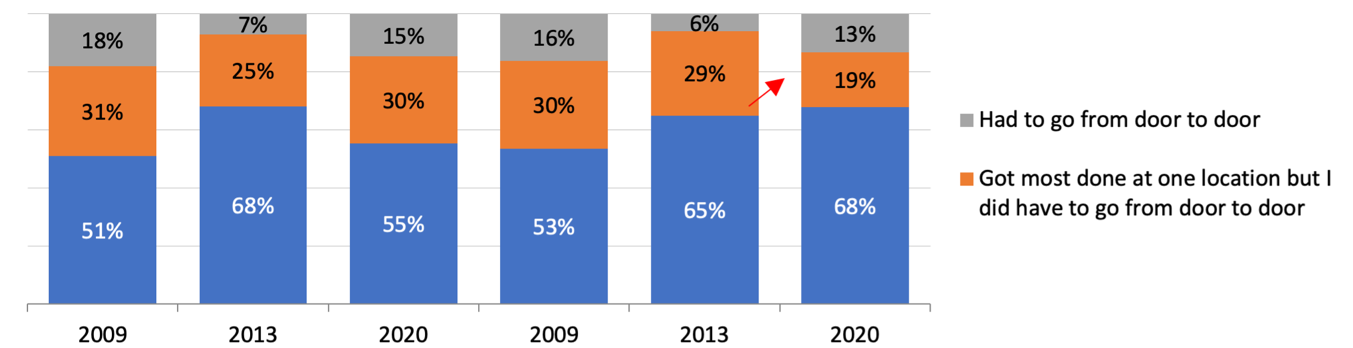

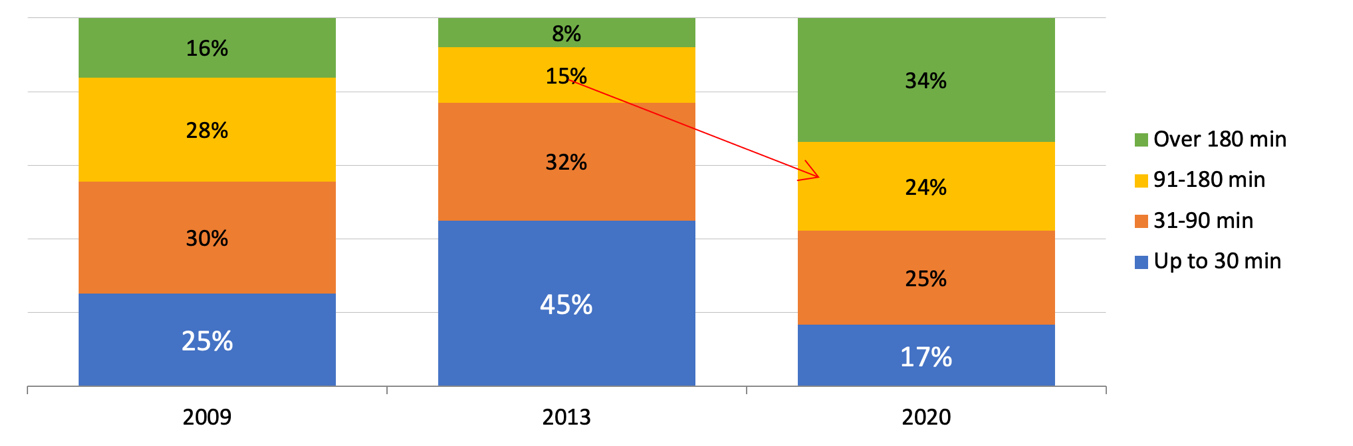

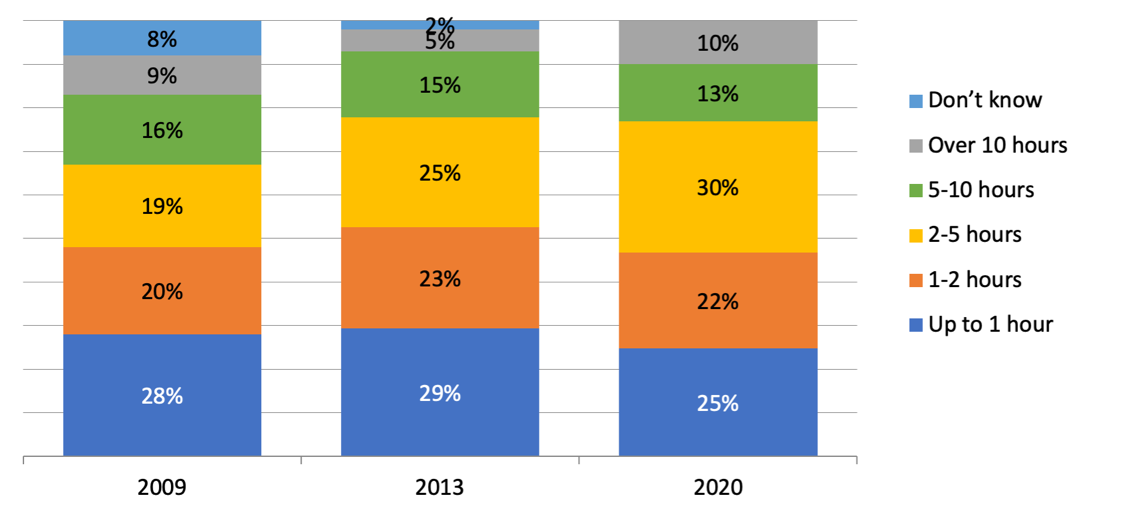

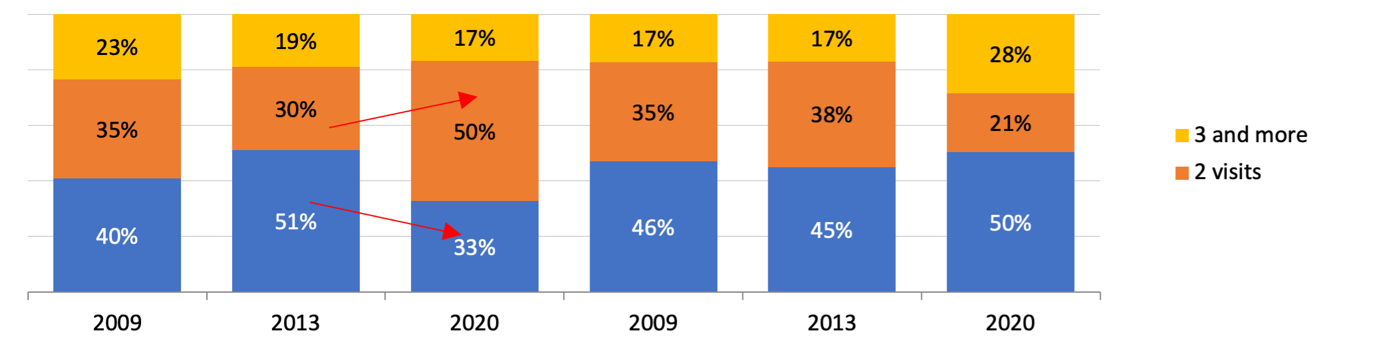

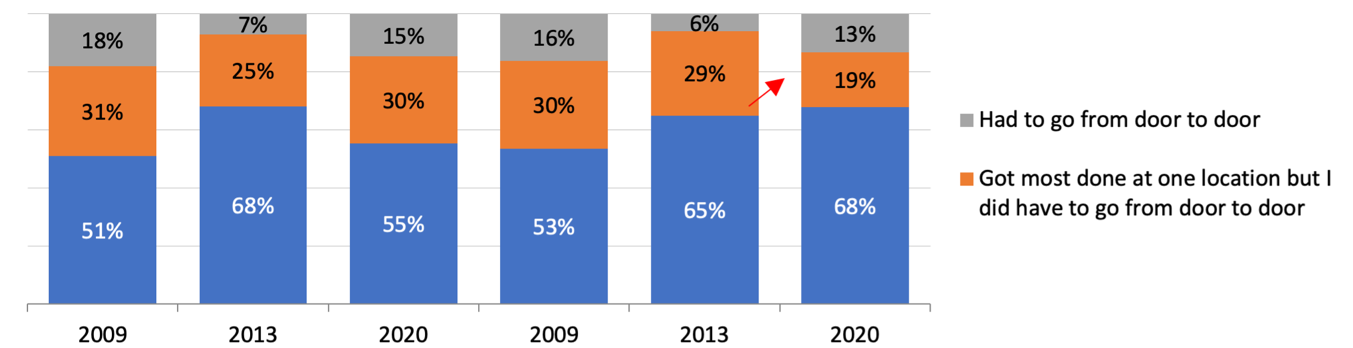

- There is room for improvement in the efficiency of

administrative tasks. Surveyed users indicated continuing

issues with having to make multiple visits, visit multiple offices, or

wait for a long time during court visits.

- Courts still had too few and inadequate means to sanction

parties and their attorneys for introducing delays in the progress of a

case. In most circumstances, it is not mandatory for judges to

discipline expert witnesses, parties, and attorneys for missing

deadlines. As well as affecting inefficiency, inconsistent application

of discipline can affect perceptions of fairness, and should be

considered in light of the chapter on Quality, which stresses the

importance of consistent application of laws.

- The SCC’s competitive Court Rewards Program put Serbia at

the forefront of innovation among European judiciaries in incentivizing

court performance. The program rewards improvement where it is

most needed.

- Meanwhile, court performance was intensely constrained by

court management and organization, practice and procedure, and party

discipline. Service of process has improved lately, but avoiding it is

still quite easy. Discipline by opposing parties in meeting

deadlines is still widely recognized as one of the main impediments of

procedural efficiency. Scheduling of hearings, the number of hearings

per case, the timeliness of their scheduling, and the frequency of

cancellations and adjournments hinder the efficiency of courts and cause

lengthy trials. The advantages of ICT tools are recognized but still not

adequately utilized.

Demand for

Justice Services (Workloads and Caseloads) ↩︎

Chapter Summary ↩︎

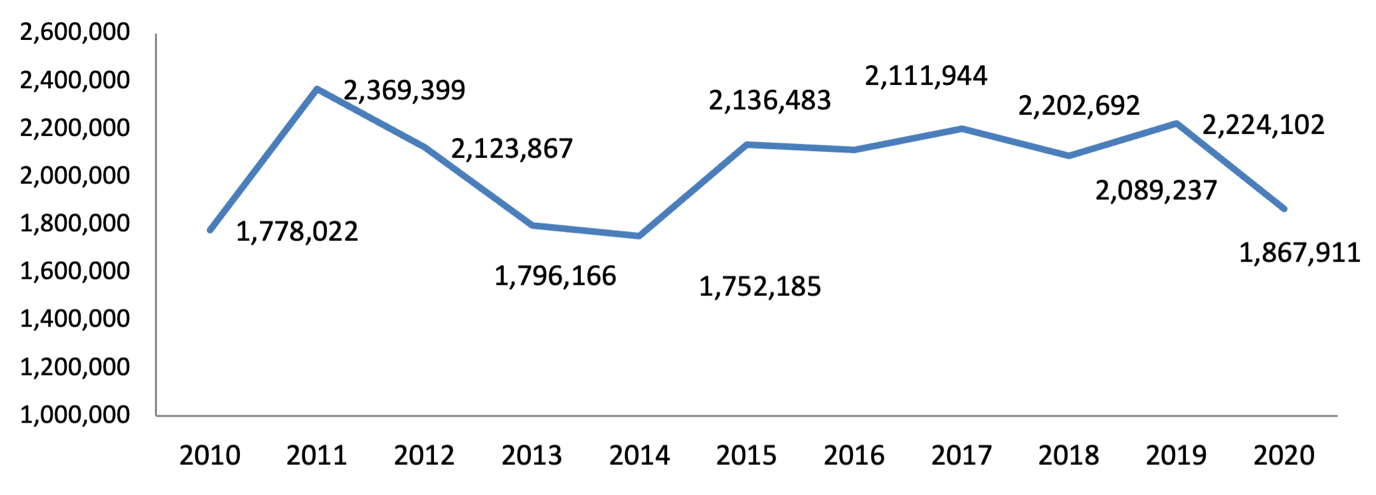

- The demand for court services in Serbia increased by 25

percent from 2010 to 2019, from a total of 1,778,022 to 2,224,102 cases

(including complex and simple matters). In 2019, 76 percent of

all incoming cases were received by Basic and Misdemeanor Courts. The

formal rise in the demand for court services in Serbia was caused partly

by recent procedural reforms and case registration practices. Judges and

court presidents interviewed by the FR team reported that judges and

staff were overburdened with work and believed that the only solution

was adding more personnel to the system. With 1,867,911 cases received

in 2020, the year heavily impacted by COVID-19 restrictions, the

incoming caseload decreased by 16 percent.

- According to the CEPEJ 2020 Report (2018 data), the

overall demand for court services in non-criminal cases in Serbia, as

reflected in its incoming cases (caseload), was higher than the EU

average, but Serbia had almost double the ratio of judges-to-population

than the EU average. Relative to population, Serbian courts

received 14.52 non-criminal cases per 100 inhabitants, while 12.34 cases

were received in EU Member States. However, with 37 judges per 100,000

inhabitants, Serbian incoming caseloads per judge were, in fact, nearly

half the EU averages.

- Caseloads were distributed unevenly among courts and

court types. Some small courts were extremely

busy, whilst larger ones were less so. Appellate Courts received a

smaller caseload on average than the SCC. In short, reforms and court

reorganizations have done little to address the uneven caseload

distributions.

- In 2019, workloads of Serbian courts reached the lowest

level in the observed period from 2010, primarily due to backlog

reductions. However, there were significant differences among

court types. The workload of Basic Courts decreased by 35 percent from

2014 to 2019, i.e., there were more than 1 million pending cases fewer,

while the workloads of Higher Courts more than doubled from 2014 to

2019, from a total of 145,345 cases to 344,205. The overall courts'

workload decreased further in 2020 as a direct consequence of lower

incoming cases and a favorable clearance rate of over 100

percent,

Introduction ↩︎

- Understanding the demand for court services as reflected

in the incoming caseloads of courts, including the type and quantity of

cases, court workloads, and their variations over time, is essential for

proper assessment of court performance. Absolute numbers should

always be put into context. To reach relevant conclusions, questions

that need to be answered are always relative and expressed in ratios,

percentages, and indicators. Whenever possible, case types are in this

FR analyzed separately, in a manner disaggregated by available

statistical reports.

Box 4: Case Weighting – the Serbian Experience

Overall Workloads and

Caseloads ↩︎

- As was true for the FR2014, overall demand for court

services is assessed in this report through caseloads and workloads

with ‘caseload’ defined as the number of incoming cases

for a given year, and ‘workload’ as the sum of the number of incoming

and pending cases for a given year.

- The rise in the demand for court services in Serbia from

2014 to 2019 was partly inflated by recent procedural reforms and case

registration practices, while caseloads and workloads continued to be

unevenly distributed among courts. Judges and court presidents

interviewed by the FR team repeatedly said that judges and staff were

overburdened with work and the only solution would be adding more

staff. The 2014 Judicial Functional Review

found a falling demand for court services in Serbia (when defined as

decreased caseloads), highly inflated caseload figures, and an uneven

distribution of cases. Serbia’s demand for court services was weaker

than EU averages; still, judges and staff throughout the system reported

feeling busy and overburdened with work. In the period covered by this

FR, the demand exceeded the EU average, while the number of judges

per capita remained one of the highest among the Council of

Europe (CoE) the Member States.

- In 2019 Serbian courts received 2,224,102 cases across

all courts. These included a large number of small matters that

should have required very little judicial work as well as a lower number

of complex cases. However, if Serbia’s court statistics did a more

sophisticated job of differentiating between simple and complex cases,

the system would have a more accurate view of its caseloads.

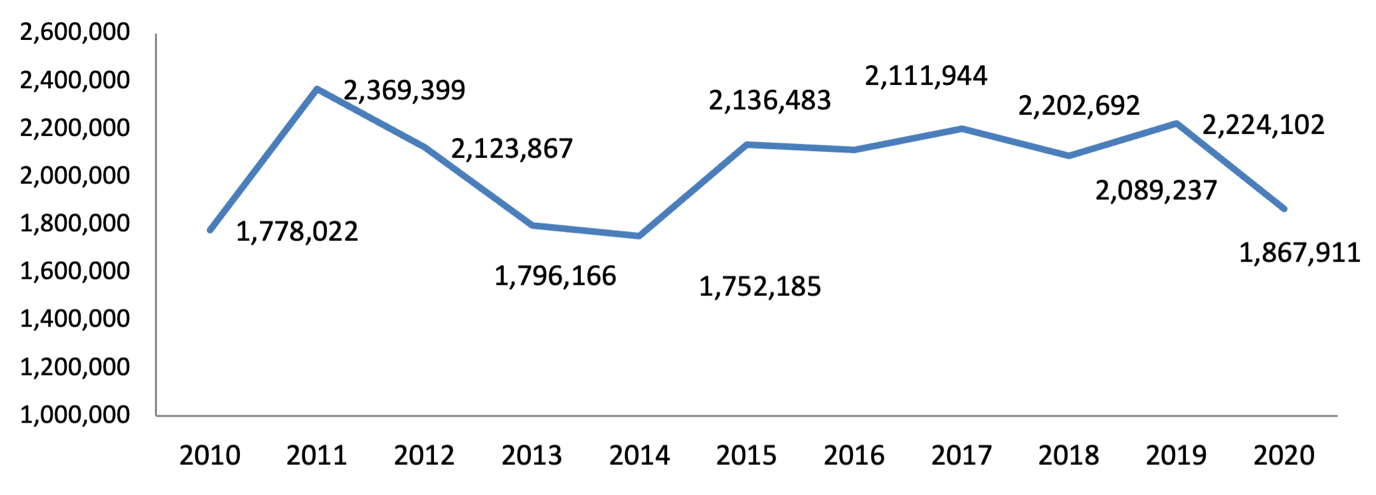

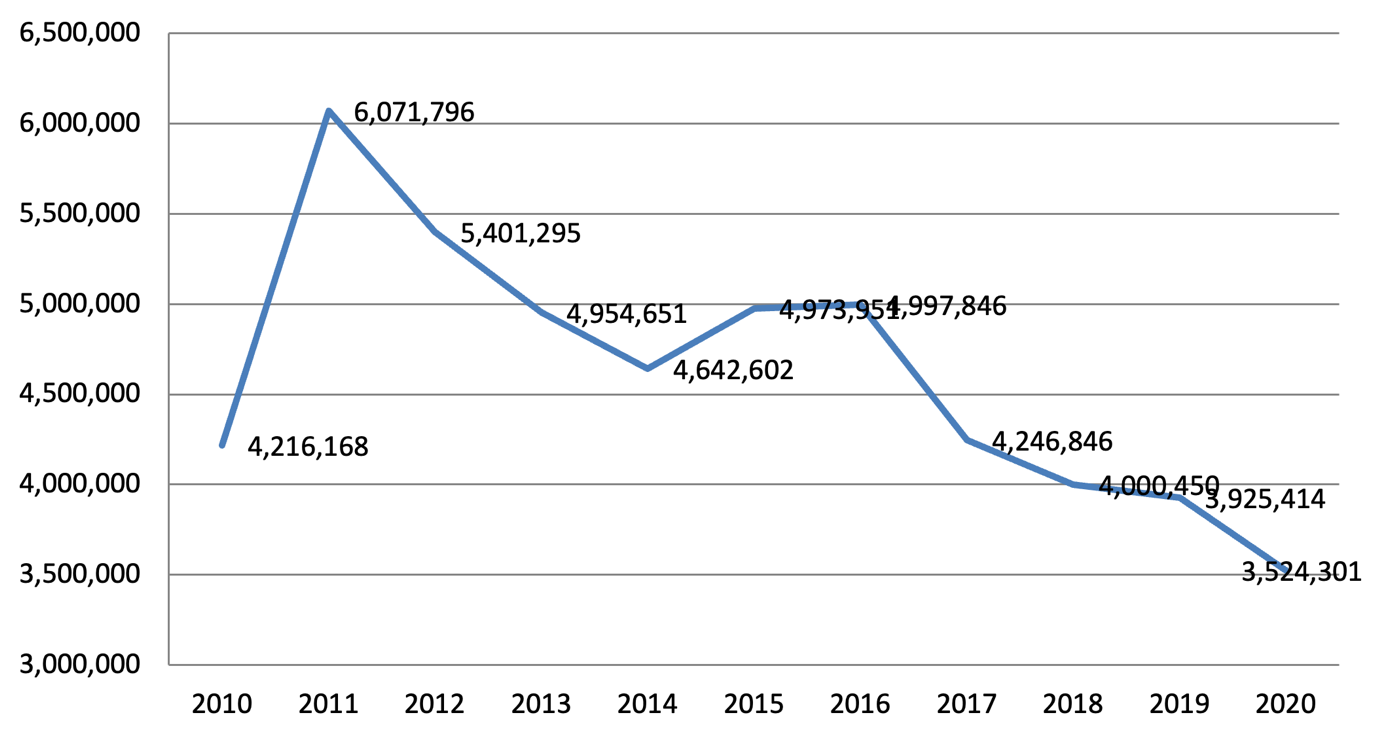

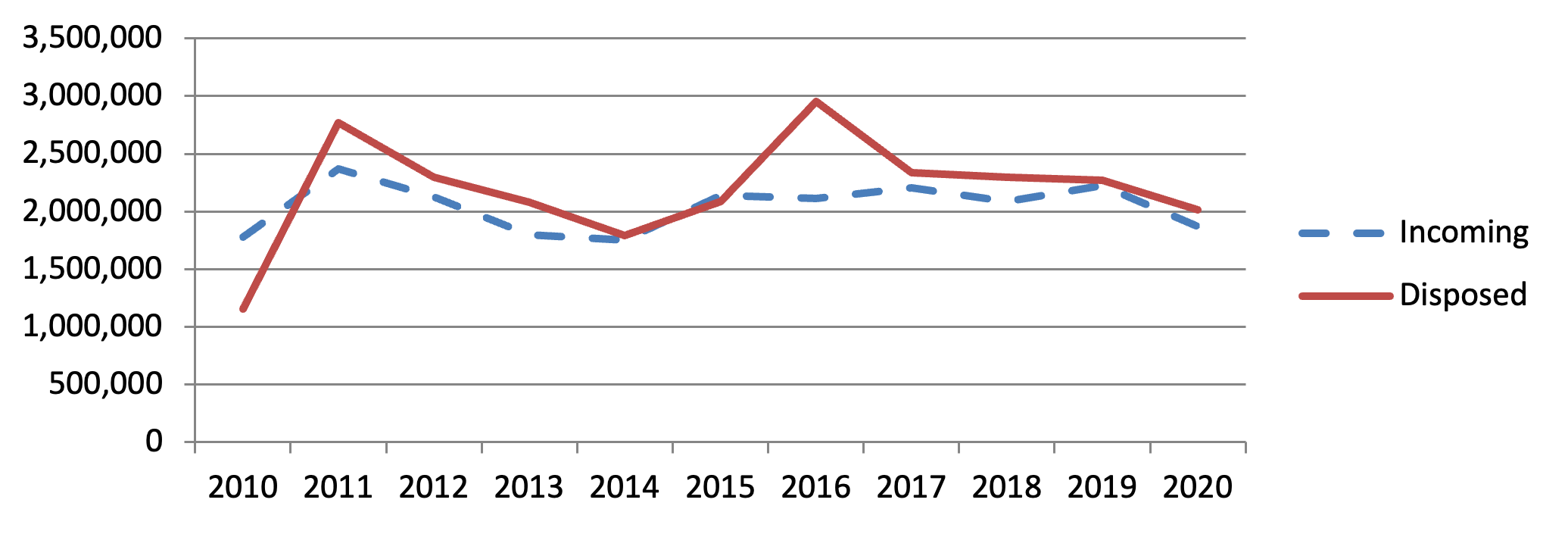

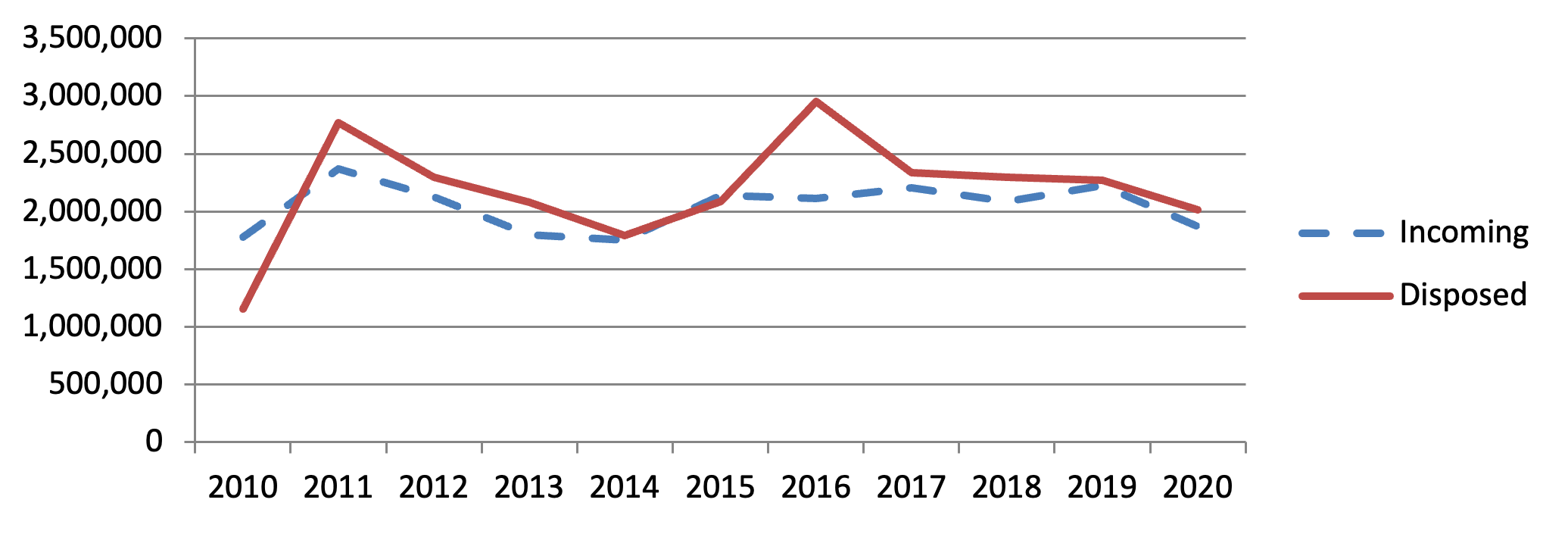

- The number of incoming cases increased by 25 percent from

2010 to 2019, as displayed in Figure 8. From 2010 to 2013 (2014

Judicial Functional Review data), these numbers had

fallen due to cuts in the types of cases being handled by courts.

Several services and types of cases were transitioned to other providers

(e.g. land registries, enforcement cases, and criminal investigations).

The decline in coming cases from 2011 to 2013 was approximately 24

percent. This pattern changed radically from 2014 to 2019; more than

400,000 more cases were received in 2019 compared to 2013. Noteworthy

portions of the increase that started in 2014 were due to case

migrations from one court to another (which often resulted in misleading

statistics about the number of cases in the system), new simple case

types, and other changed practices, as analyzed in more detail below. In

2020¸ 1,867,911 cases were received, 16 percent cases fewer in

comparison to 2019, primarily due to COVID-19 restrictions that caused

lower demand for court services.

Figure 8: Incoming Cases in Serbia from 2010 to 2020

Source: SCC Data

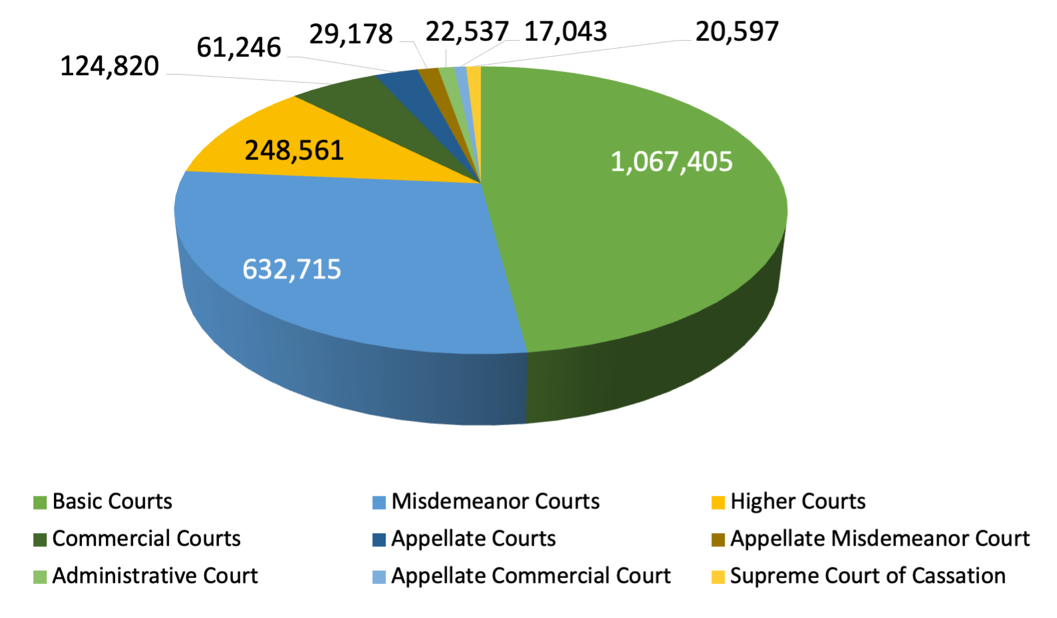

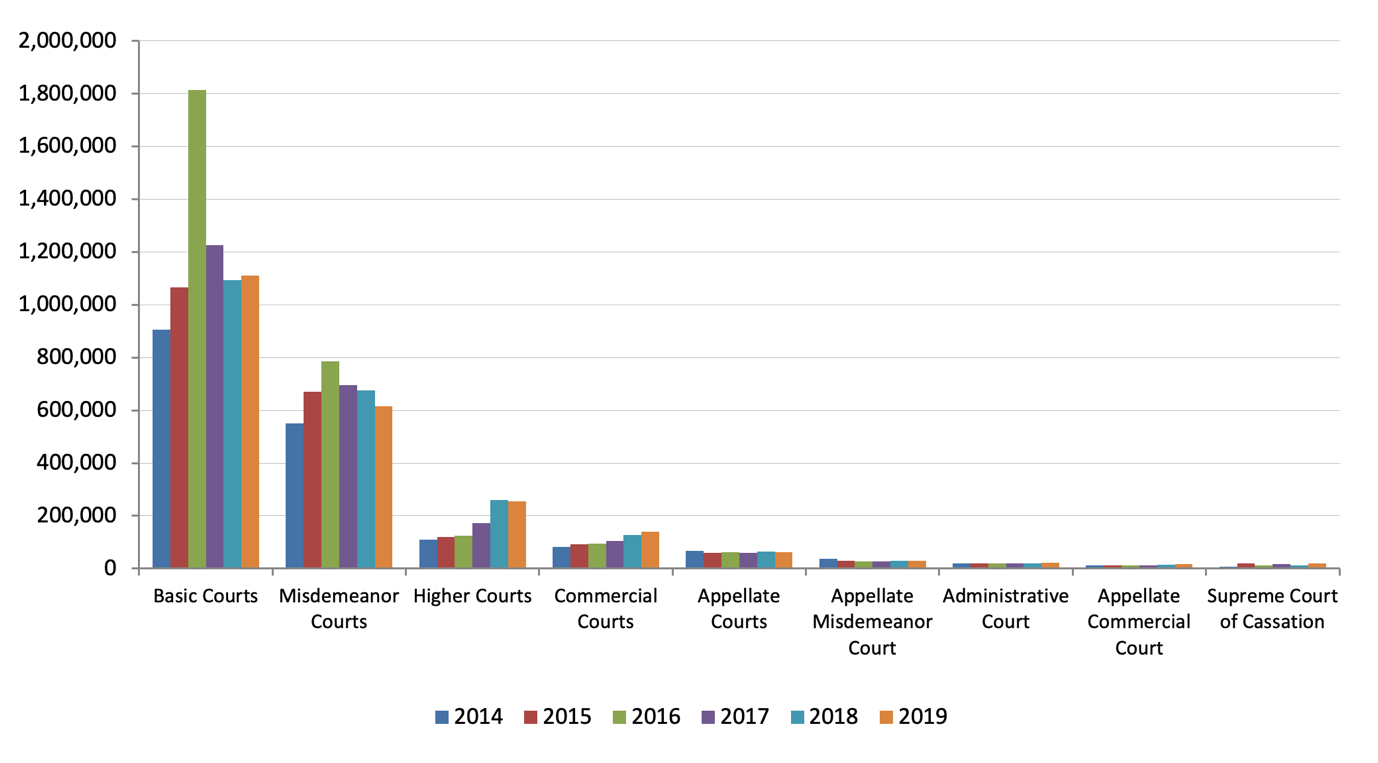

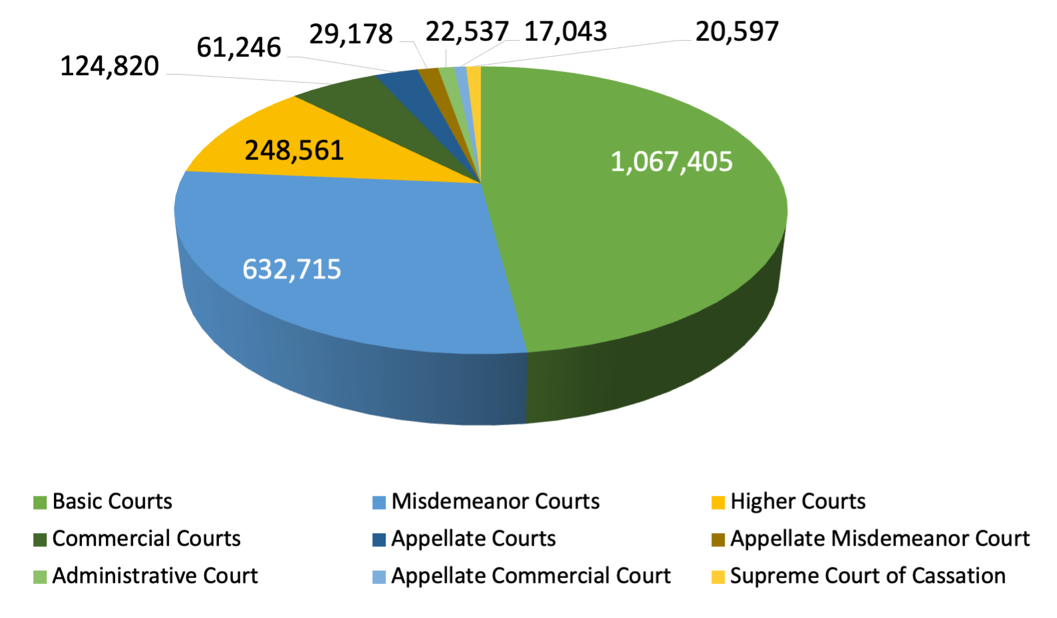

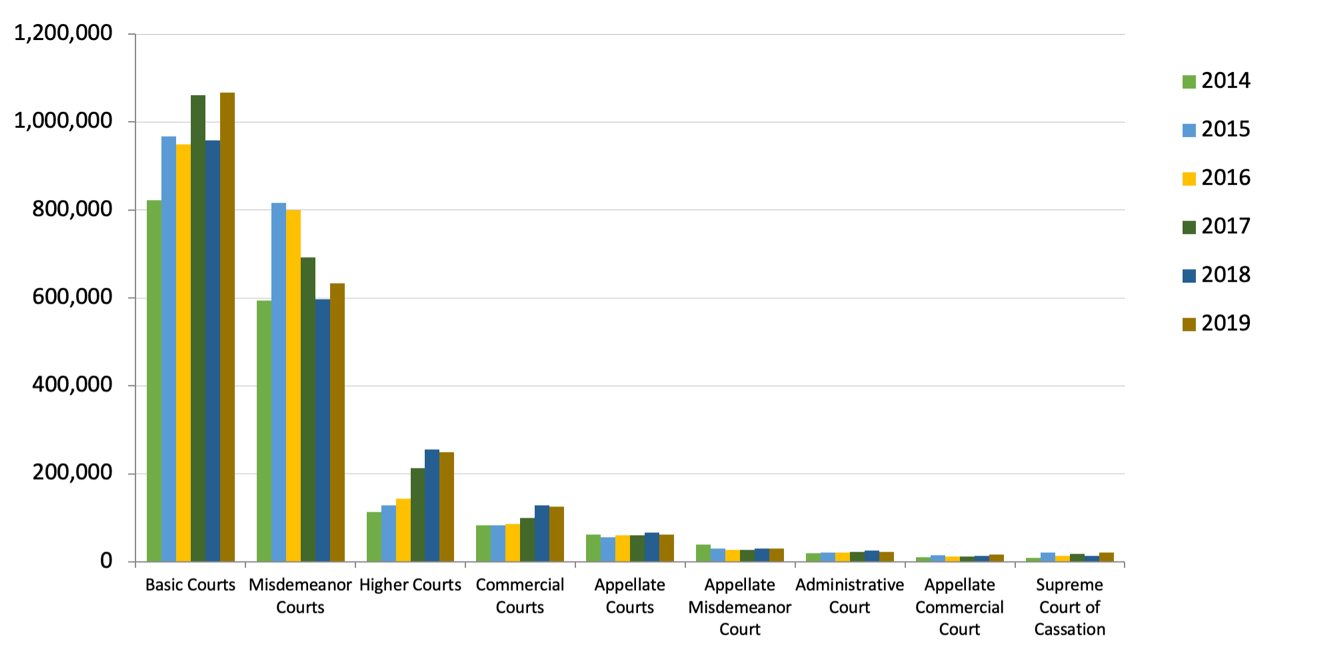

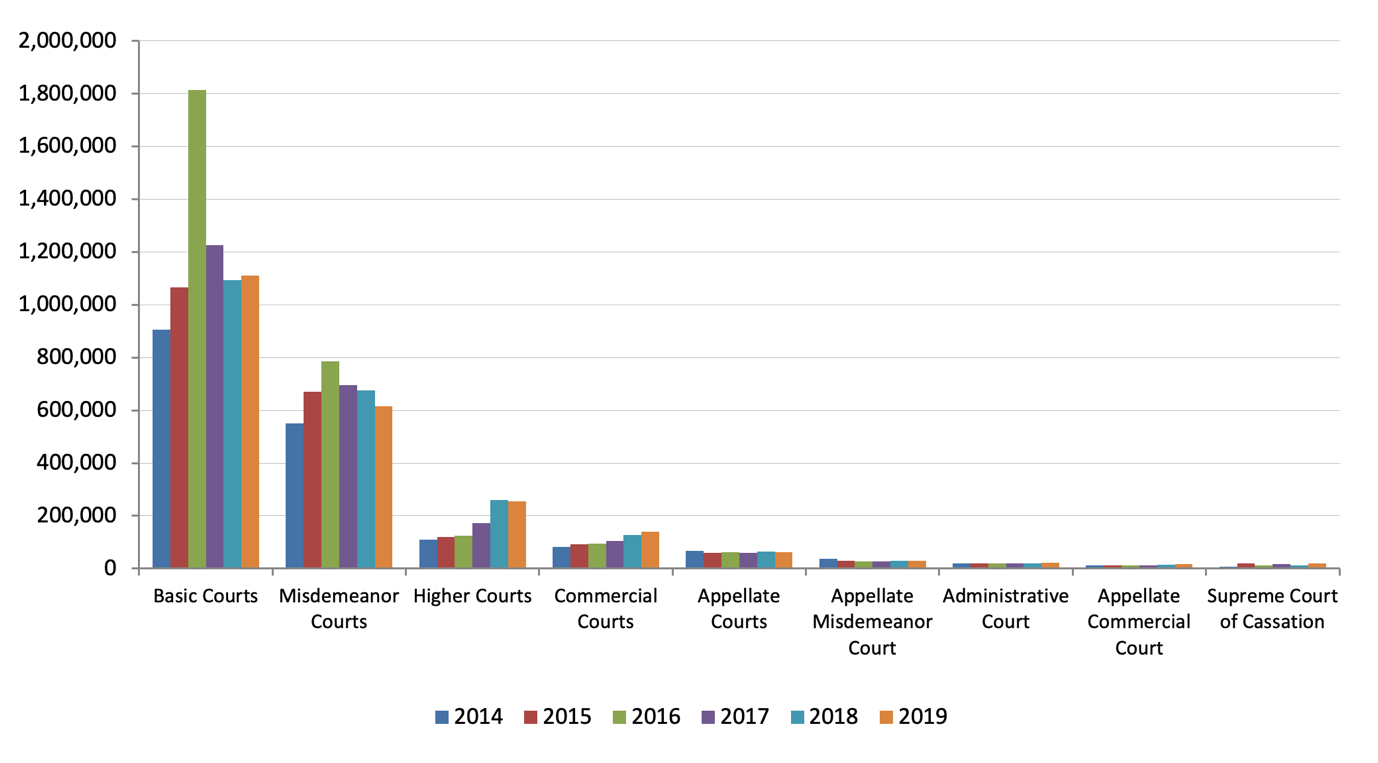

- Basic and Misdemeanor Courts received the highest number

of cases in 2019, together accounting for 76 percent of all incoming

cases. Basic Courts received more than 1 million cases; the

Misdemeanor Courts received approximately 600,000 cases and the Higher

Courts just under 250,000 cases. Commercial Courts received more than

124,000 cases, and the total for other court categories was 150,601,

although none of the other court types had more than 100,000 cases.

Figure 9 displays the breakdown of incoming cases across court types in

2019.

Figure 9: Incoming by Court Type in 2019

Source: SCC Data

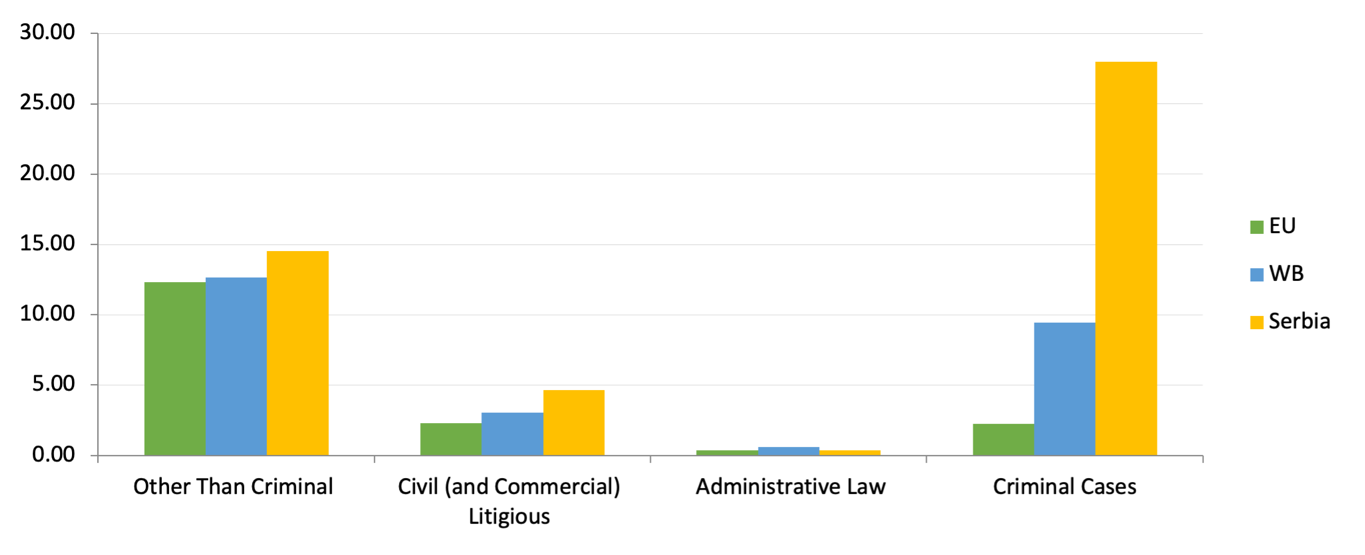

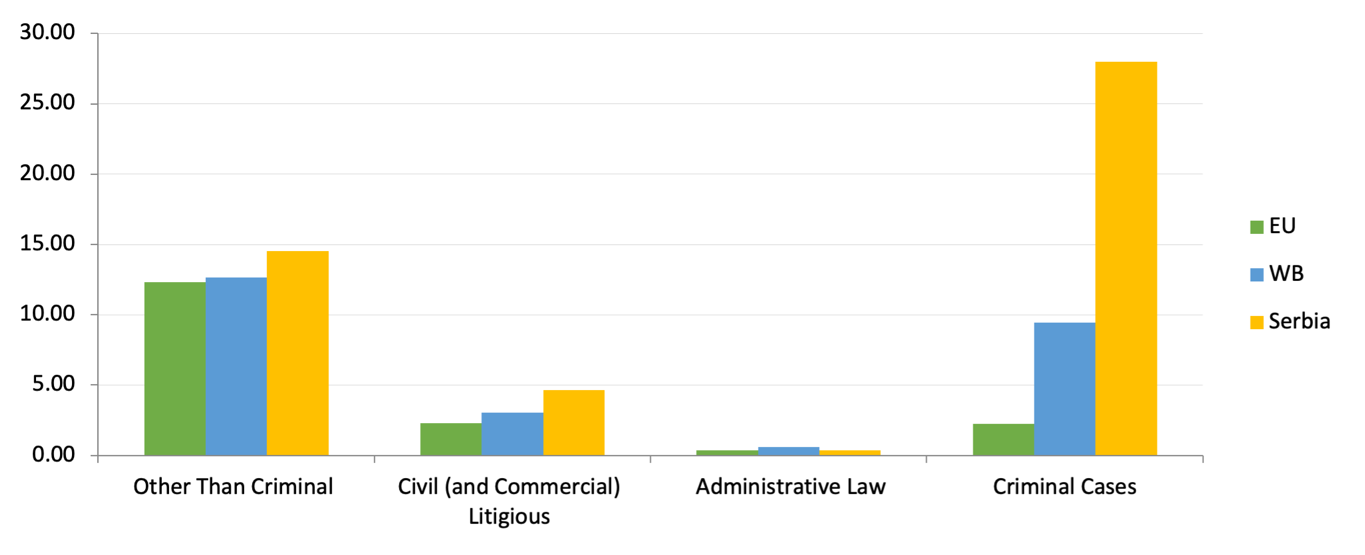

- According to the CEPEJ 2020 Report (2018 data) the overall demand for

court services in Serbia, as reflected in incoming non-criminal cases,

was higher than the EU average. Relative to population, the

Serbian courts received 14.52 non-criminal cases per 100 inhabitants,

while 12.34 cases were received in the EU Member States and 12.65 in the

Western Balkans. Serbia’s demand for non-criminal

cases, as defined above, increased by seven percent compared to the

CEPEJ 2018 report (2016 data). This means that in 2018 around one in

seven Serbians had a non-criminal case in court.

- The CEPEJ 2020 Report found the demand for court services

in criminal cases in Serbia was 12 times greater than the EU

average. According to the CEPEJ, the number of incoming

criminal cases per 100 inhabitants increased by 12 times from 2012 to

2014 (from 0.88 to 10.60) and then reduced somewhat in 2016 (although

the number remained high at 7.07). The 2014 increase was caused by

Serbia’s new reporting methodology, which included misdemeanor cases and

commercial offenses in the category of criminal cases.

It is also probable that the differences in criminal case numbers were

affected by the variety of legal systems and reporting methodologies in

CoE Member States. For instance, in the 2020 evaluation cycle that used

2018 data, CEPEJ introduced a new subcategory of criminal cases named

“other” which in Serbia’s case most probably inflated the average with

various criminal cases, some of them mentioned in this

Functional Review as so-called ‘KR’ cases.

Figure 10: Incoming First Instance Cases per 100 Inhabitants (CEPEJ

2020 report)

Source: CEPEJ 2020 Report (2018 data)

- For severe criminal cases,

as reported by CEPEJ Serbia was under the EU average.

Serbia reported 0.74 incoming severe criminal cases per 100 inhabitants

in the 2020 Report (2018 data), while the EU average was 0.82. There

were 51,708 incoming cases of this type in 2018, representing one-tenth

of the reported total of criminal cases. This essentially was the same

percentage as severe criminal cases occupied in 2016.

- Meanwhile, with 37

judges per 100,000 inhabitants, Serbia reported almost double

the ratio of judge-to-population of the EU average. The only EU

Member States and Western Balkans countries with higher

judge-to-population ratios were Serbia’s neighbors Slovenia (42),

Croatia (41), and Montenegro (50). The incoming caseloads

per judge in Serbia were, in fact, nearly half the EU averages.

- Caseload statistics in Serbia remained highly

inflated. As the 2014 Judicial Functional Review reported,

Serbia counts many matters as ‘cases’ that would not be considered as

cases in comparative systems (i.e., in COE or EU Member States), so the

case numbers reported in this FR were inflated by matters that require

very little or no attention from judges rather than their staffs.

Serbia’s numbers were even more inflated by double-counting since the

same legal matter can be assigned multiple case numbers over time. For

instance, cases were counted as dispositions in one court when the

matter was delegated or transferred to another, and the receiving court

would assign a new number to the case and count it as an incoming

matter. The number of cases susceptible to double-counting during the

period analyzed in this FR meant no one in the judiciary could have a

reliable sense of how many cases requiring the attention of a judge were

in the system. This impedes the reliability of statistical reports,

especially when it comes to probate cases entrusted to public notaries

or enforcement cases transferred among courts,

as discussed further in this analysis.

- Rather than correcting inflated numbers of ‘cases’ and

their implications for judicial workloads, many if not most stakeholders

in Serbia accepted the reported numbers at face

value. The reported failure of some courts to

apply the applicable rules about court statistics consistently made the

reliability of the statistics even more questionable, for the system as

a whole, across categories of courts, and for individual

courts.

Caseloads and Workloads

by Court Type ↩︎

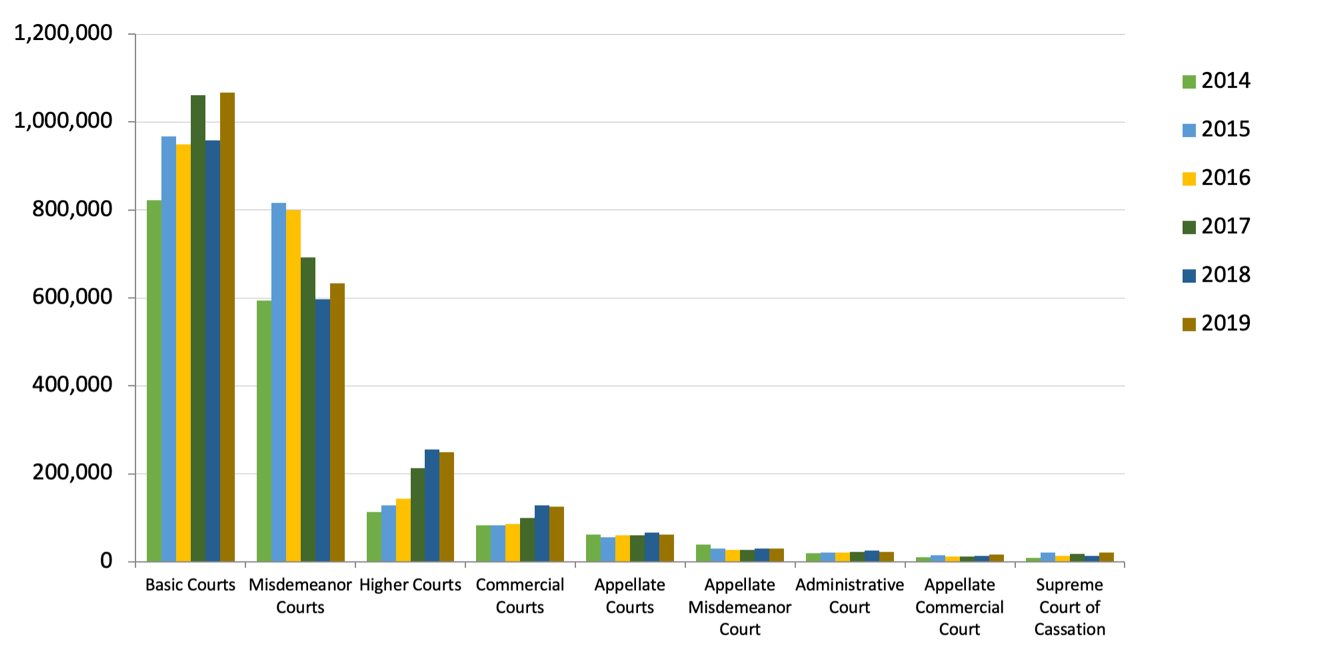

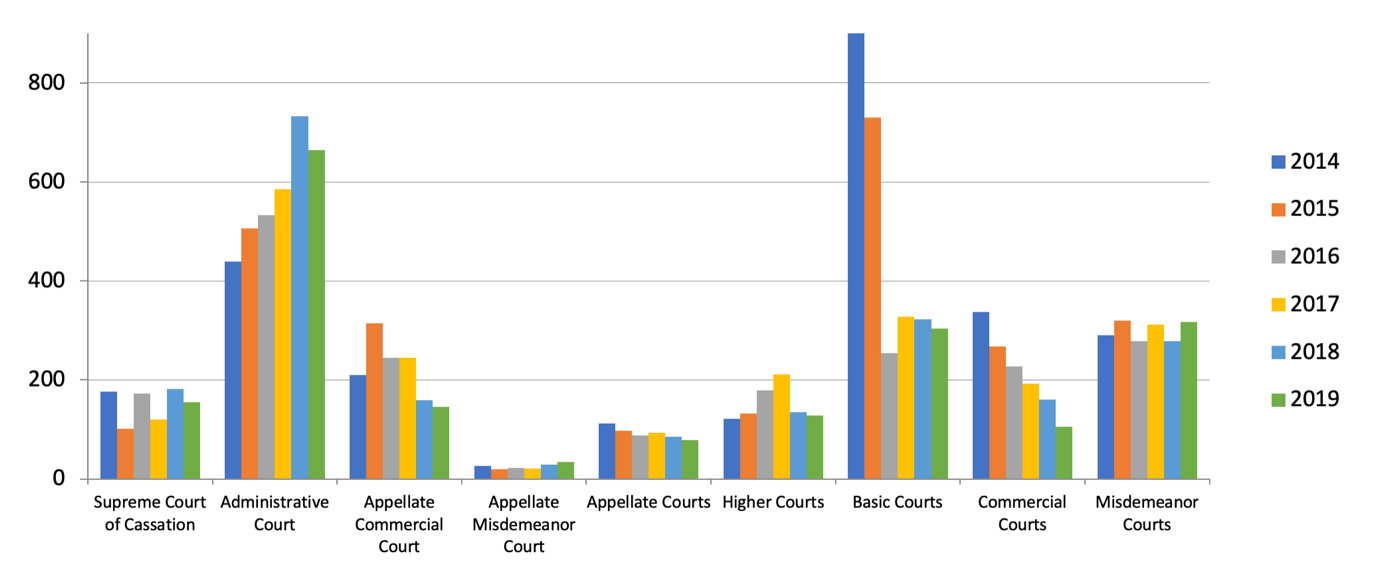

- The demand for justice services varied among court types

over the years from 2014 to 2019. The Higher Courts, the

Commercial Courts, and the Administrative Court reported increases each

year from 2014 to 2018, but in 2019 these court types all recorded a

slight decline. In other types of courts, demand fluctuated. Trends are

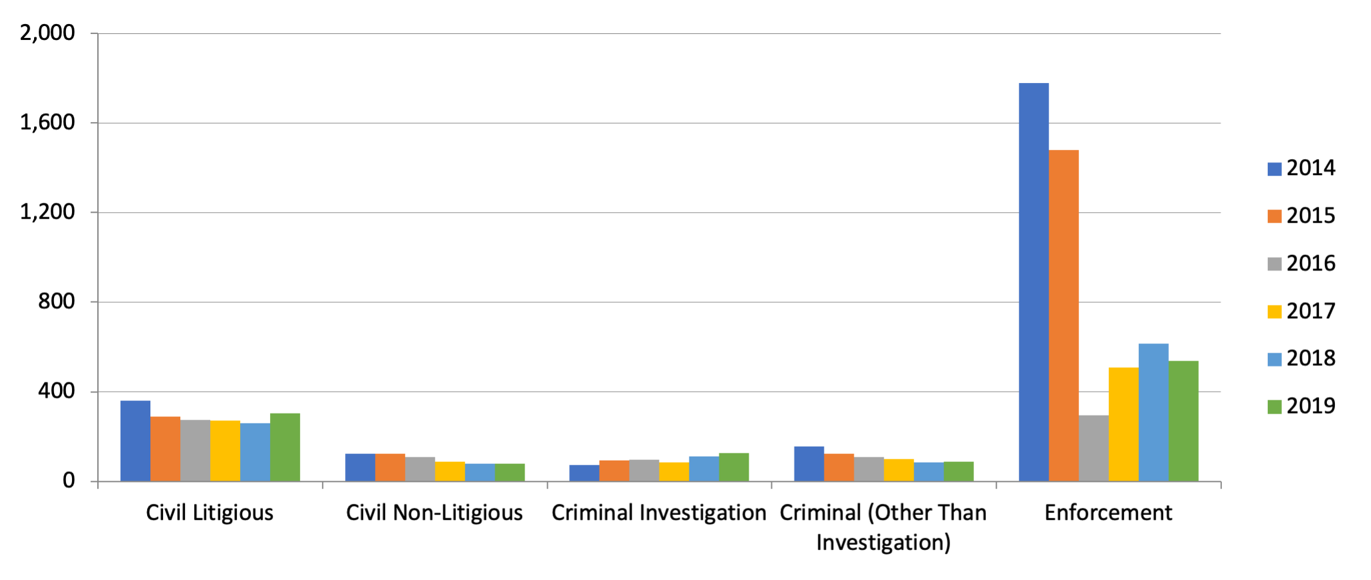

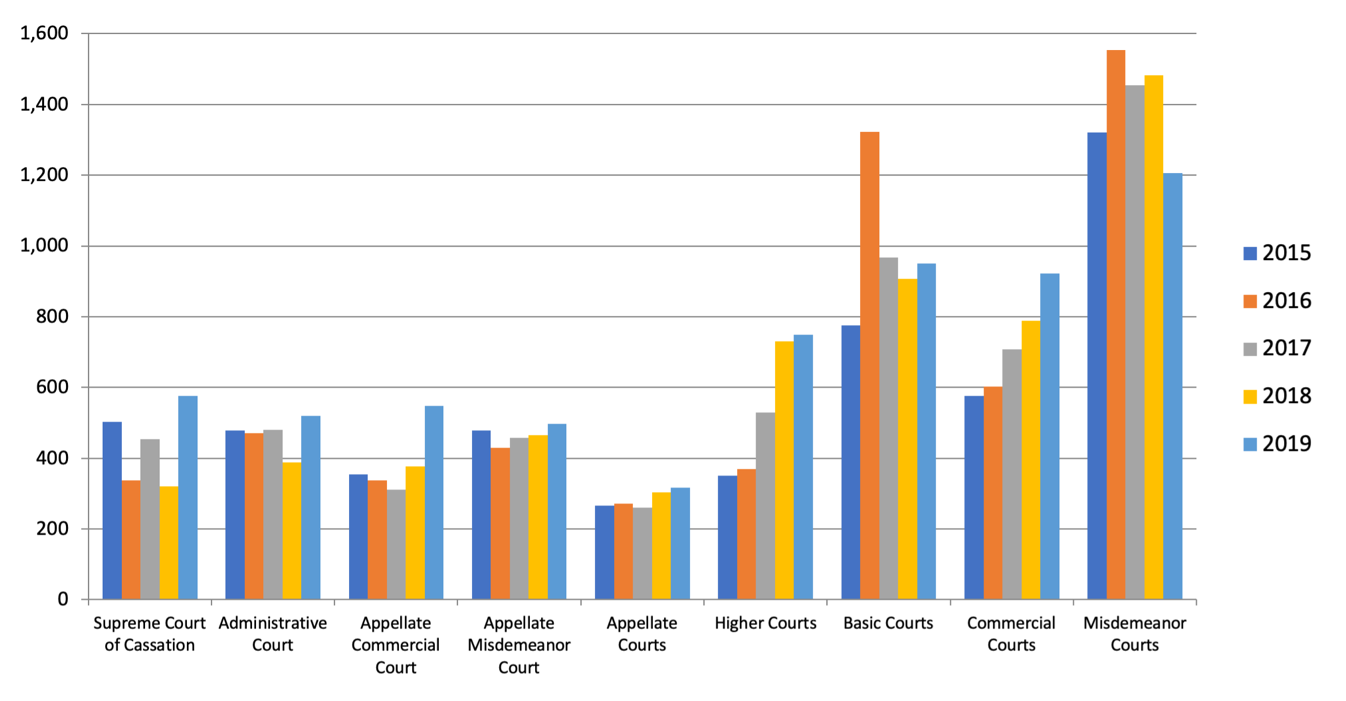

displayed in Figure 11 below.

Figure 11: Incoming Cases by Co$urt Type from 2014 to 2019

Source: SCC Data

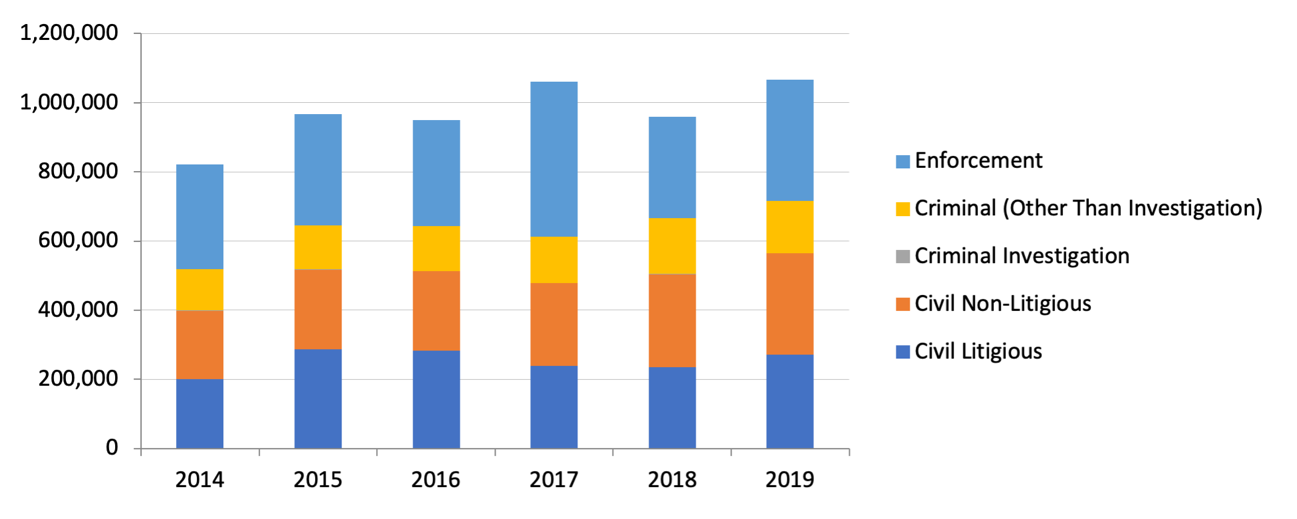

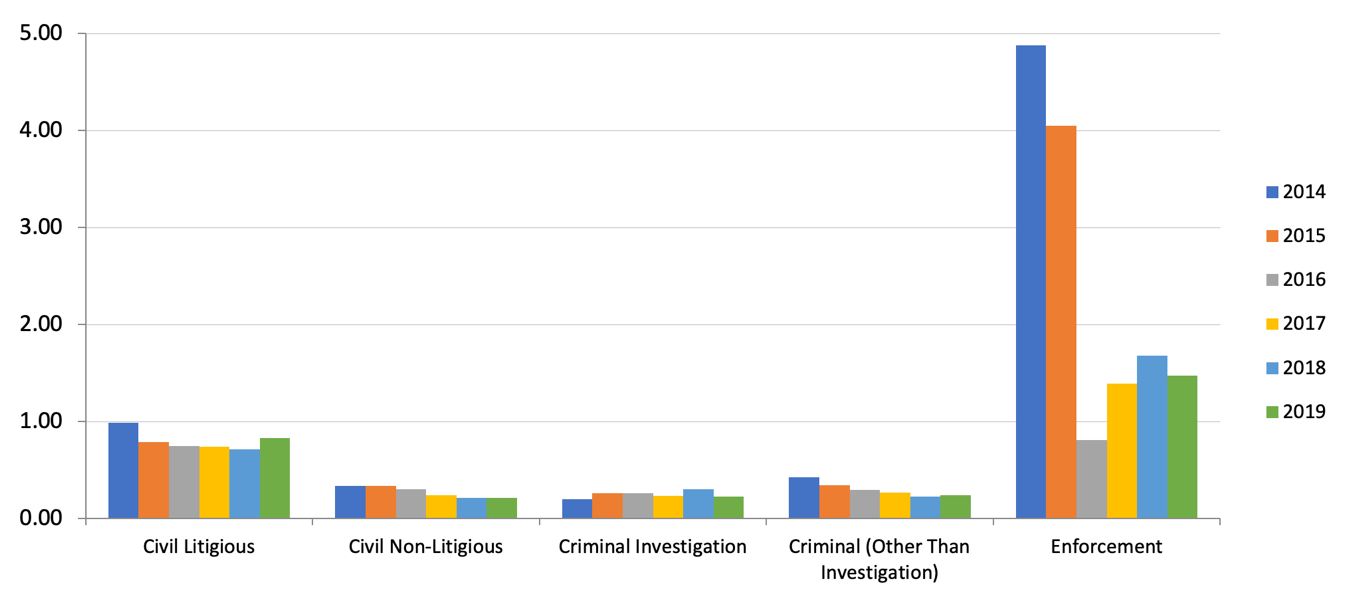

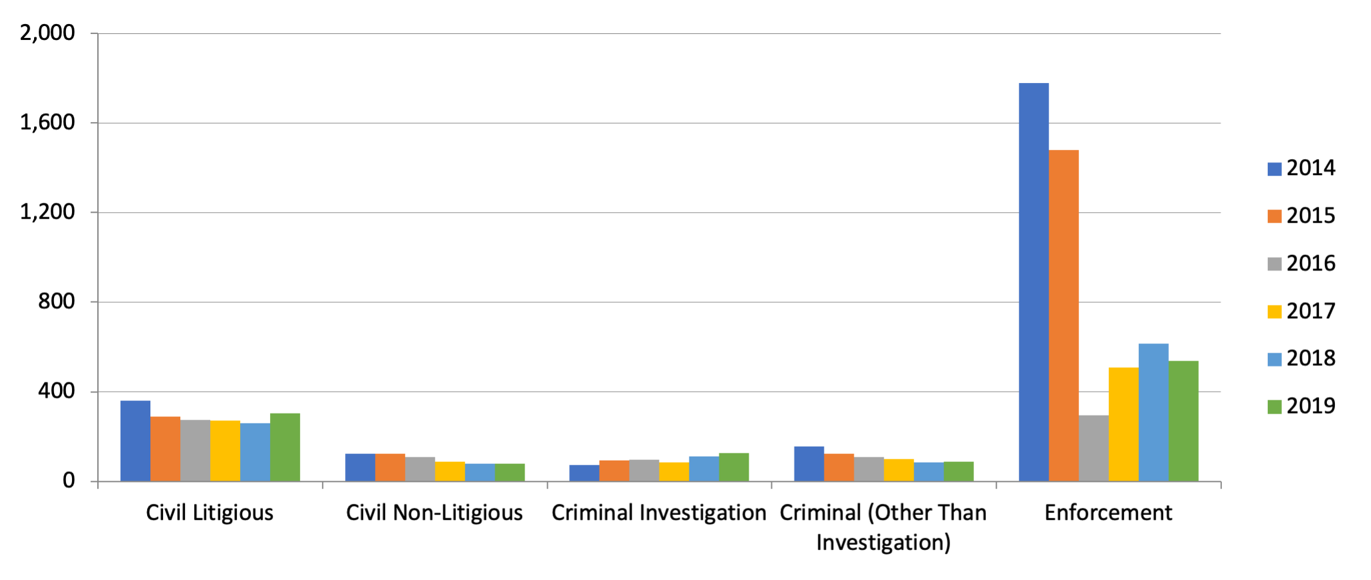

- The number of incoming cases in Basic Courts rose after

2014, which was not foreseen in the 2014 Judicial Functional

Review. In 2019 the number of incoming

cases increased by 30 percent compared to 2014 and there was a similar

increase in 2017. Although all incoming case types grew (excluding

criminal investigations), the most significant contributors

to the rise in demand were litigious and non-litigious civil cases, as

displayed in Figure 12 below. The primary cause of the reduction in

demand recorded in 2018 was the decrease in the number of incoming

enforcements.

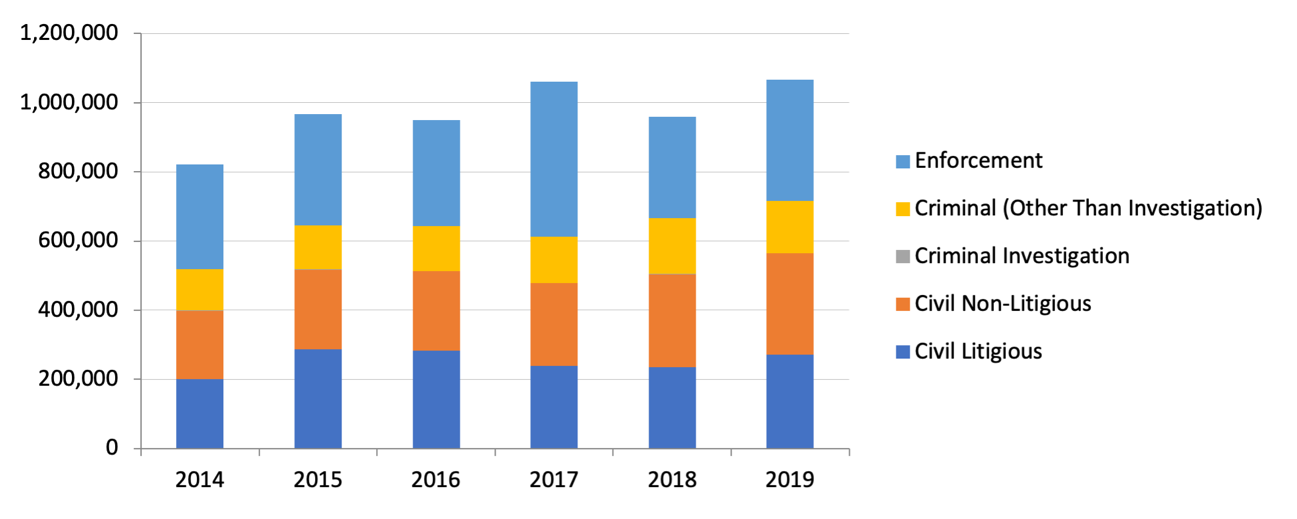

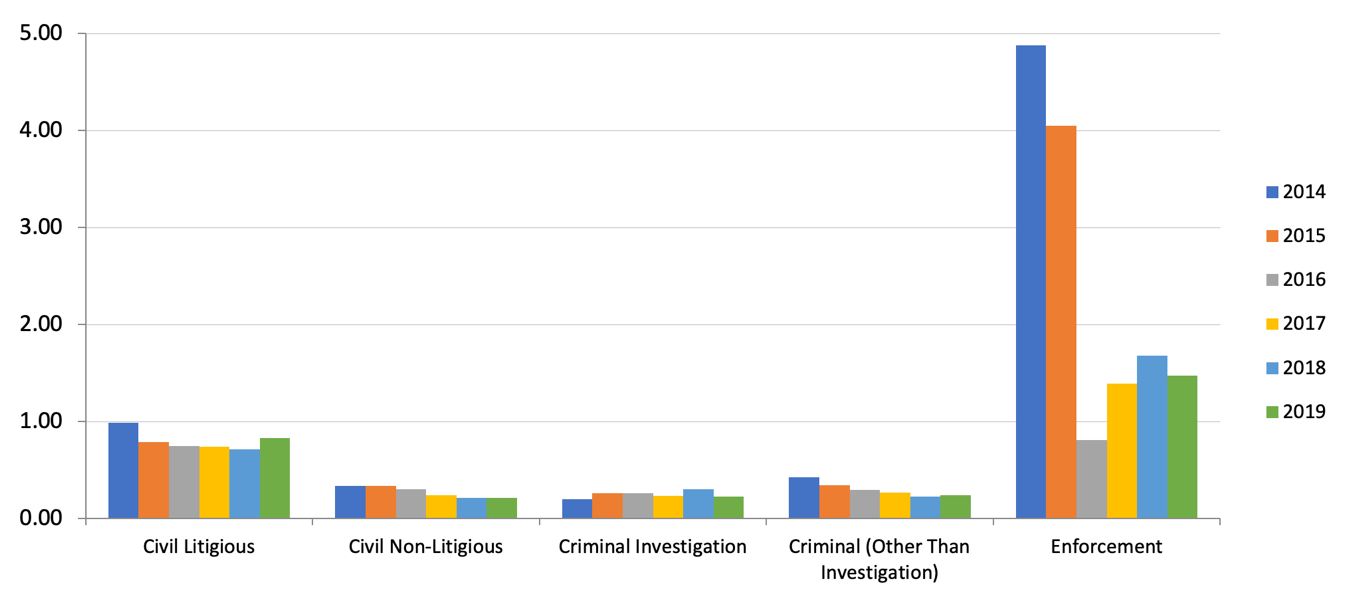

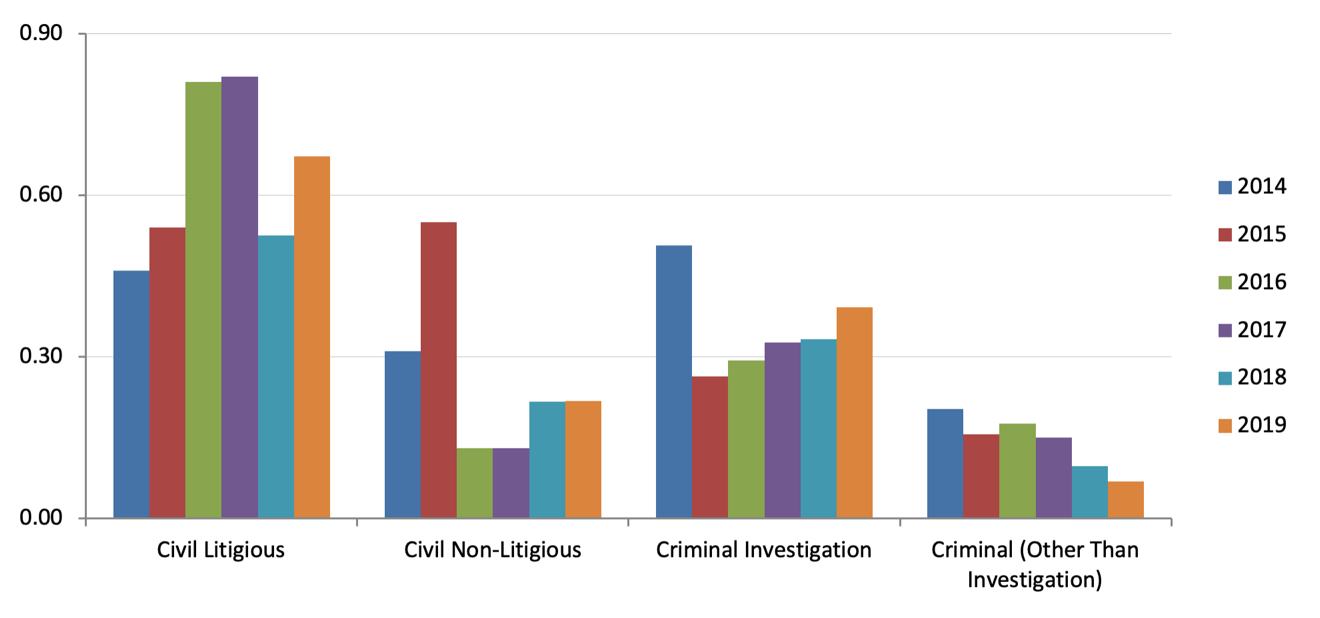

Figure 12: Incoming Cases by Case Type in Basic Courts from 2014 to

2019

Source: SCC Data

Table 3: Incoming Cases by Case Type in Basic Courts from 2014 to

2019

| Civil Litigious |

200,576 |

287,320 |

282,433 |

238,290 |

235,801 |

270,765 |

| Civil Non-Litigious |

198,294 |

230,275 |

230,029 |

240,375 |

268,532 |

294,255 |

| Criminal Investigation |

998 |

527 |

383 |

127 |

127 |

80 |

| Criminal (Other Than Investigation) |

118,599 |

126,616 |

130,055 |

133,465 |

161,347 |

151,146 |

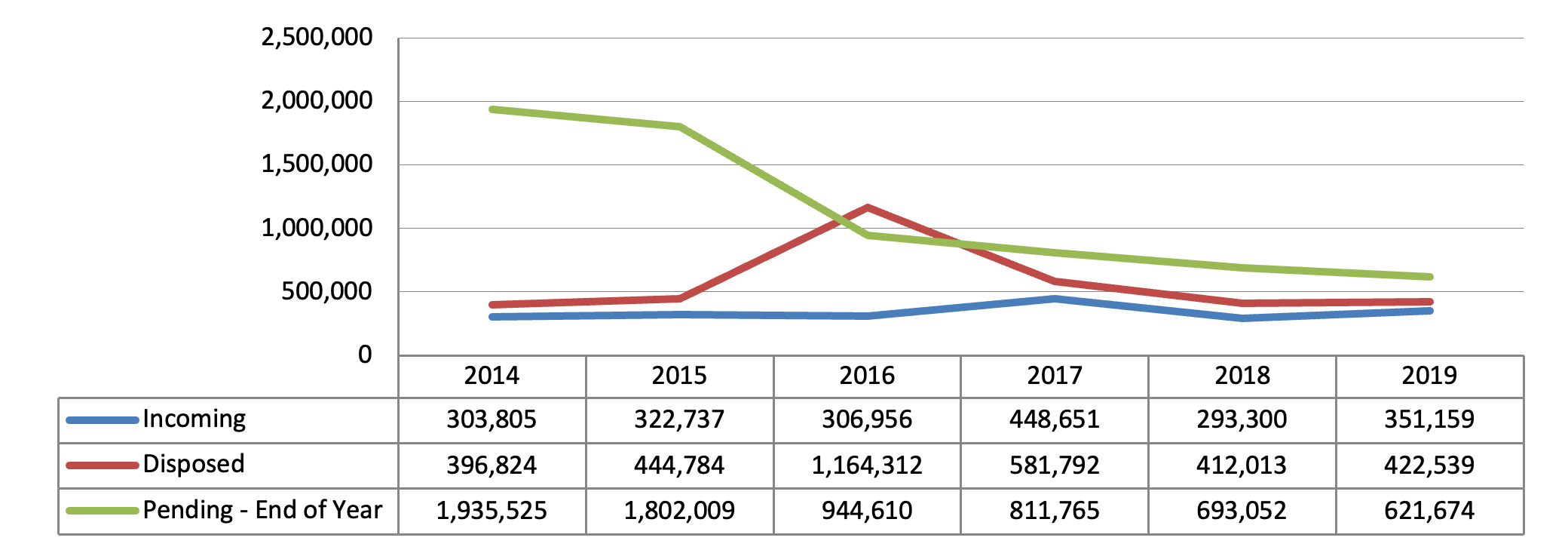

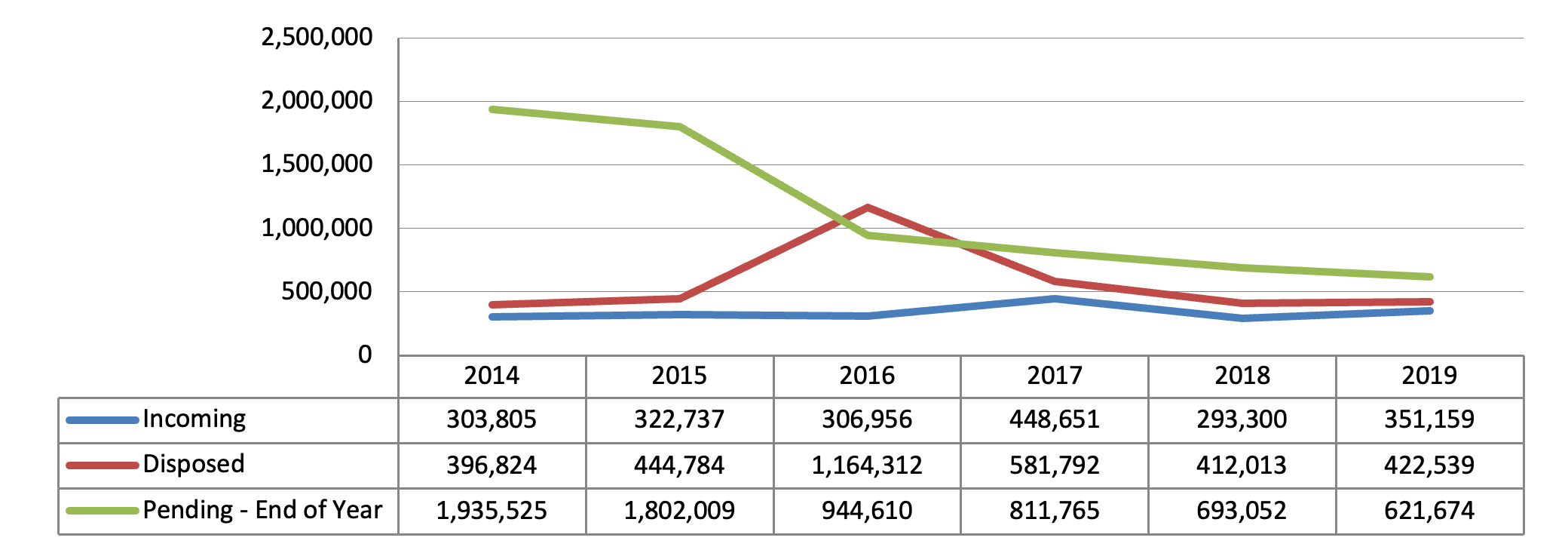

| Enforcement |

303,805 |

322,737 |

306,956 |

448,651 |

293,300 |

351,159 |

Source: SCC Data

Box 5: Enforcement Cases and Their Impact on Overall Court

Results

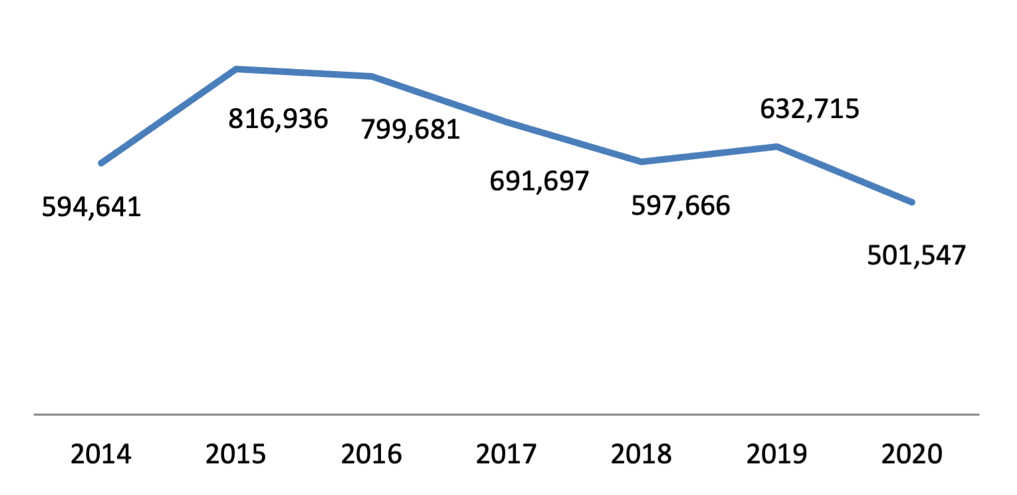

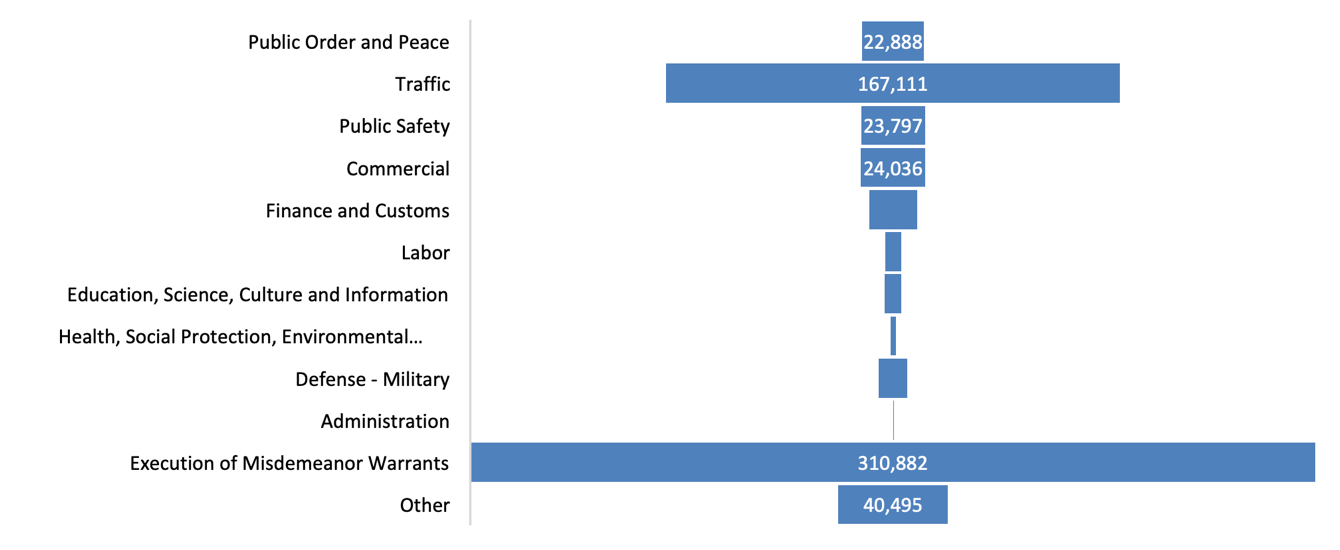

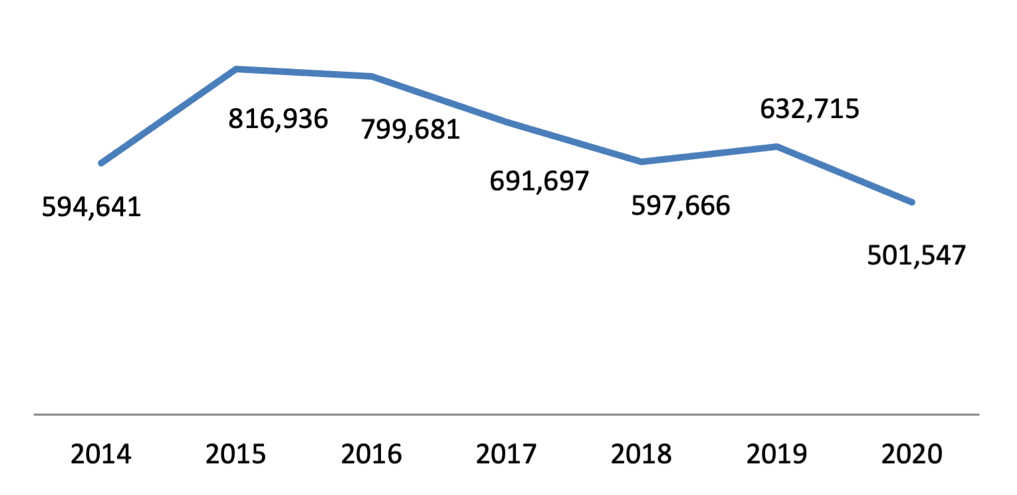

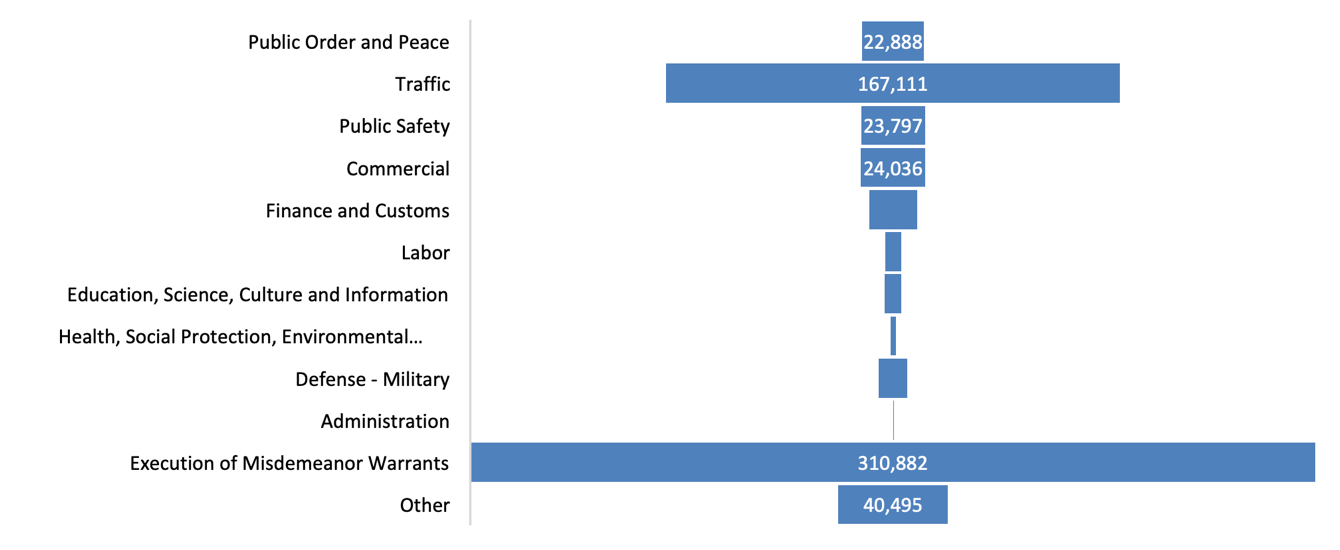

- Incoming caseloads of Misdemeanor Courts increased

dramatically in 2015 and 2016, primarily due to a specific types of

execution cases. In 2019, Misdemeanor Courts received 632,715

cases. Expectedly, most of the courts’ caseload (almost one-third) was

related to 167,111 incoming traffic cases. As displayed in Figure 13

below, peaks were recorded in 2015 and 2016, when approximately 200

thousand more cases were received. The increase was generated by

traffic, public safety, and finance and customs matters. And what was

even more significant by extreme jumps in misdemeanor execution cases of

so-called ‘misdemeanor warrants’. Around 39 percent of

all misdemeanor cases in 2019 were received in Belgrade’s Misdemeanor

Court (247,222), while the lowest numbers were received in Misdemeanor

Courts in Presevo (1,709) and Sjenica (1,232). The caseload of

Misdemeanor Courts decreased by 21 percent in 2020.

Figure 13: Incoming Cases in Misdemeanor Courts from 2014 to 2020

Source: SCC Data

Box 6: The New Law on Misdemeanors

Figure 14: Incoming Cases in Misdemeanor Courts by Case Type in

2019

Source: SCC Data

- The growth of commercial offenses in Commercial Courts is

a prime example of how poorly planned legislative changes can create

even more burdens for the judicial system. In the Commercial

Courts incoming cases have grown steadily, amounting to 124,820 in 2019,

which was a 51 percent increase from 2014 but a three percent drop from

2018. This effect was driven by a five-fold increase in received

commercial offenses, which increased to seven-fold in 2018. The

Accounting Act requires the Business Register

Agency to submit complaints about commercial offenses against all legal

entities that did not submit annual financial statements or statements

of inactivity. In 2014, prior to the application of this provision, the

Commercial Courts received just over 4,000 commercial offenses. By 2018

this figure had grown to almost 31,000. In 2019 it declined for the

first time since 2014 to 23,000. These cases posed a burden not only to

courts but also for the assigned public prosecutors.

- The Higher Courts’ caseload more than doubled from 2014

to a total of 248,561 in 2019. Incoming cases grew each year of

the period from 2014 to 2018 by 13, 12, 48, and 20 percent,

respectively. In 2019, a slight decline of three percent was

recorded.

- Incoming criminal cases (other than investigations) in

Higher Courts were stable at around 50,000 until 2018, when almost

90,000 criminal cases were received, and in 2019 the incoming caseload

jumped again to more than 120,000. The majority of the increase

consisted of purely bureaucratic cases related to inquiries of other bodies whether criminal

proceedings are being conducted against an individual, received in the

Higher Court in Belgrade registered under 'KR Po1’. In 2018 25,846

incoming 'KR Po1’ cases were reported (43 times more than in 2017) and

in 2019 there were 55,842 (93 times more than in 2017). The other

category with significant increases consisted of the same case type

registered under ‘KR’ (6,883 in 2019 incoming cases, twice as many as in

2017). It caused significant increases in 'KR’ cases among eight of the

25 Higher Courts, while others

received only a few or none of them. Criminal investigation cases

remained at around 3,000, although with a slightly increasing

tendency.

- The number of civil litigious

cases in Higher Courts grew rapidly, as presented in

Figure 15 below. From 2016 to 2017, the number

of incoming litigious cases almost doubled, while in 2018 it grew by

only two percent. Conversely, in 2019 a drop of 31 percent was reported.

Overall, civil non-litigious cases more than tripled from 2014 to 2019,

from 5,428 to 18,173.

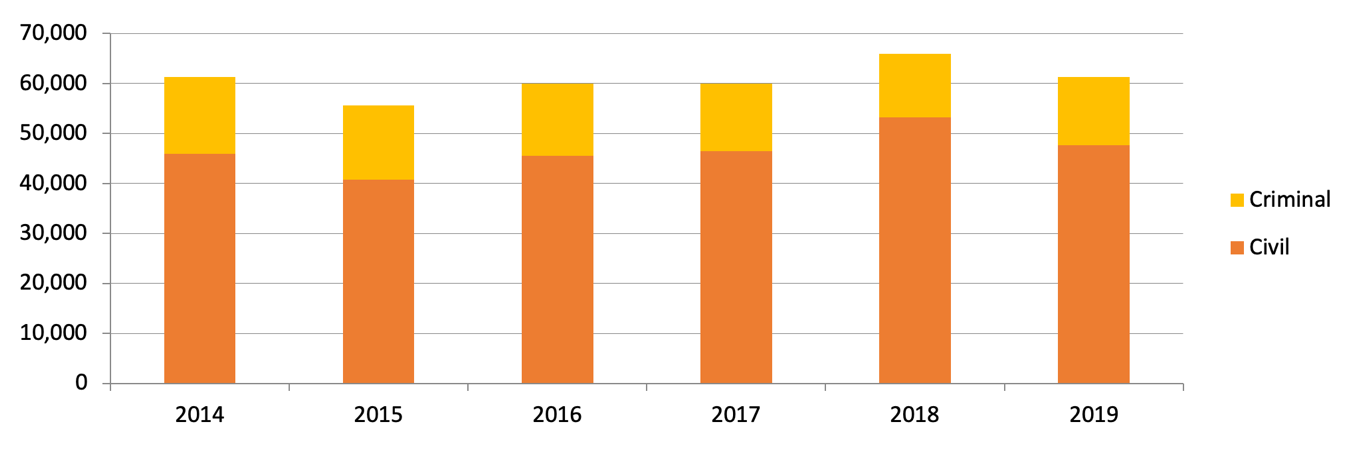

Figure 15: Incoming Cases by Case Type in Higher Courts from 2014 to

2019

Source: SCC Data

- According to the SCC

the primary cause of the increased caseload of litigious cases

in 2017 was the glut of 56,342 first-instance civil

matters filed by military reservists. These repetitive cases,

which challenged the amount reservists were receiving as financial

benefits, could have been be disposed of by a so-called ‘pilot decision’

of the SCC which has been, according to the Civil Procedure Code, used

for case law unification. These 56,000 cases probably were not the only

cause for the high number of new civil litigious cases in 2017 and 2018,

but the available data and interviews did not identify any other single

driver behind them.

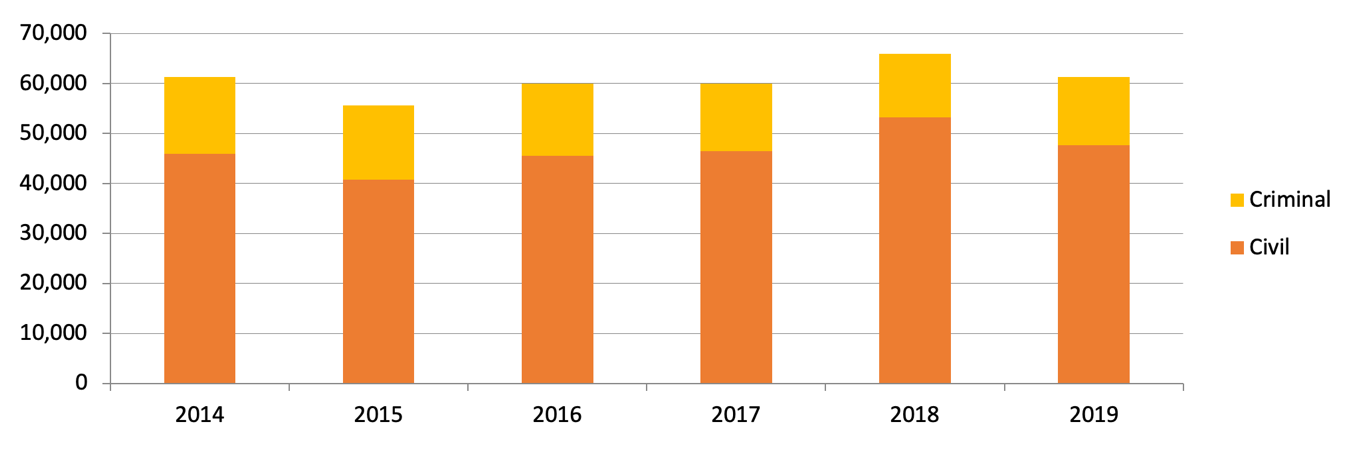

- The Appellate Courts had a reasonably stable caseload

throughout the period, as displayed in Figure 16

below. Nevertheless, compared to the period covered by the 2014

Judicial Functional Review their caseload decreased by roughly 40

percent, mostly due to the reduced numbers of incoming criminal cases.

Still, the SCC reported in its 2017 Report that

the effects of the military reservist cases had started to spill over to

the Appellate Courts, and that more should be expected in 2018. In fact,

2018 incoming civil cases in Appellate Courts did grow by 14 percent

over the previous year, but available data did not show if it was the

reservist cases that caused the growth.

Figure 16: Incoming Cases by Case Type in Appellate Courts from 2014

to 2019

Source: SCC Data

- The SCC’s caseload of civil cases more than doubled from

2014 to 2019 – from 6,971 to 18,182, largely due to an expansion of the

Court’s jurisdiction in 2014.

Revision cases grew each year; from 3,735

in 2014, to 5,480 in 2015, 5,732 in 2016, 7,102 in 2017, 9,907 in 2018

and 10,531 in 2019. The revision threshold was reduced to 40,000 EUR and

a so-called ‘special revision’ was introduced as a

new extraordinary legal remedy, causing the caseload to increase. Nevertheless, the overall civil

caseload of the SCC was, to some extent, inflated by delegation cases

registered under ‘R’ (issues posed by delegations also are discussed at

Section 1.3.2.2. Case Dispositions, below). In 2015 there were

7,123, in 2017 there were 6,734, and in 2019 there were 6,469 ‘R’ cases

included in the incoming caseload of the SCC, while in the other

observed years, there were no more than 200 of these simple matters.

Criminal incoming cases in the SCC varied modestly over the years from a

minimum of 1,539 cases (registered in 2015) to a maximum of 1,898 cases

(registered in 2016).

- The Administrative Court experienced a constant increase

in its incoming caseload until 2019, when it declined by 11

percent. It received 19,423 cases in 2014, 20,315 in 2015,

21,548 in 2016, 21,741 in 2017, 25,426 in 2018, and 22,537 in 2019. This

increase was consistent with the continuous expansion of the Court's

jurisdiction through new laws relating to restitution, protection of

labor rights of employees working in local government and electoral

cases, among others.

- The 25 percent reduction in the caseload of the Appellate

Misdemeanor Court from 2014 to 2019 was instigated by the elimination of

two types of cases from its jurisdiction related to public procurement

and sentencing. The Appellate Misdemeanor Court received 39,103

cases in 2014, 29,583 cases in 2015, 26,658 cases in 2016, 26,444 cases

in 2017, 29,702 cases in 2018, and 29,178 cases in 2019. The reduction

was attributable to the elimination of appeals in the court lodged

against decisions of the Republic Commission for Protection of Rights in

Public Procurement Procedures and appeals concerning the substitution of

a fine for imprisonment. The former category dropped from 9,879 incoming

cases to only nine, while the latter decreased from 3,059 to 340

incoming cases. Other incoming case types varied through the period, but

their influence on the total caseload of the Court was much weaker. For

instance, there were almost 10 percent more traffic cases received in

2018 than in 2014.

Box 7: Misdemeanors Related to Public Procurement

Demographic Differences in

Demand ↩︎

- Calculated for all courts, Serbia’s incoming caseload

grew from 24.38 cases per 100 inhabitants in 2014 to 30.95 cases per 100

inhabitants in 2019. Not surprisingly,

the highest incoming numbers by court type in 2019 were recorded in

Basic and Misdemeanor Courts with 14.85 and 8.80, respectively. Trends

in demand per 100 inhabitants per court type are detailed in Figure 17

below.

Figure 17: Incoming Cases by Court Type per 100 Inhabitants in First

Instance Courts from 2014 to 2019

Source: SCC Data and WB Calculations

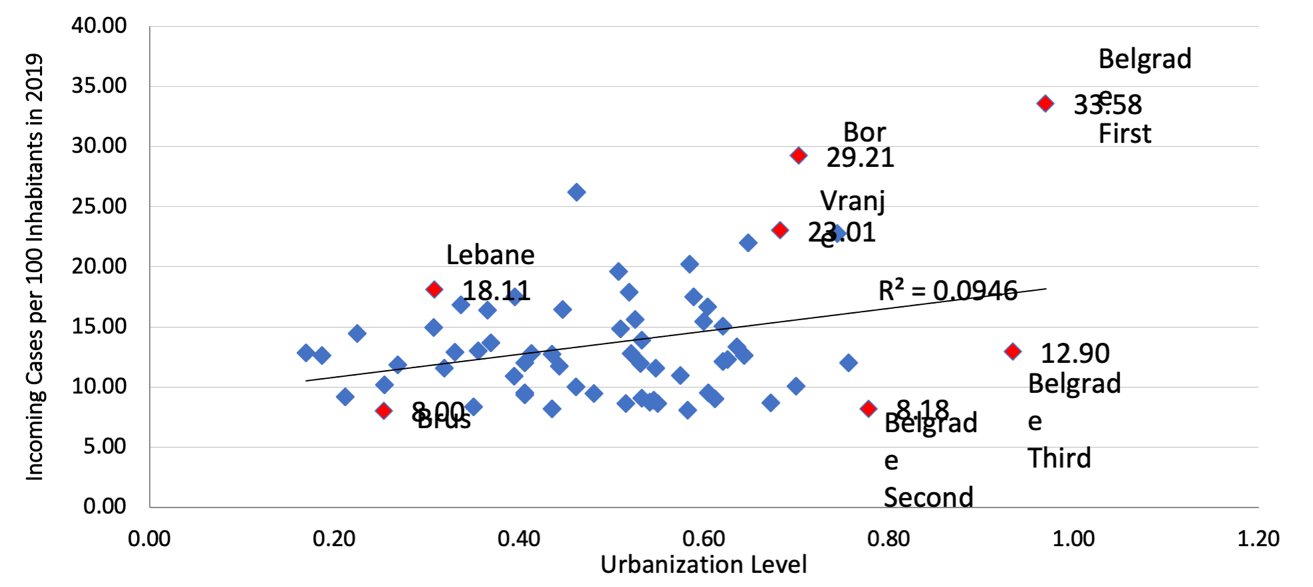

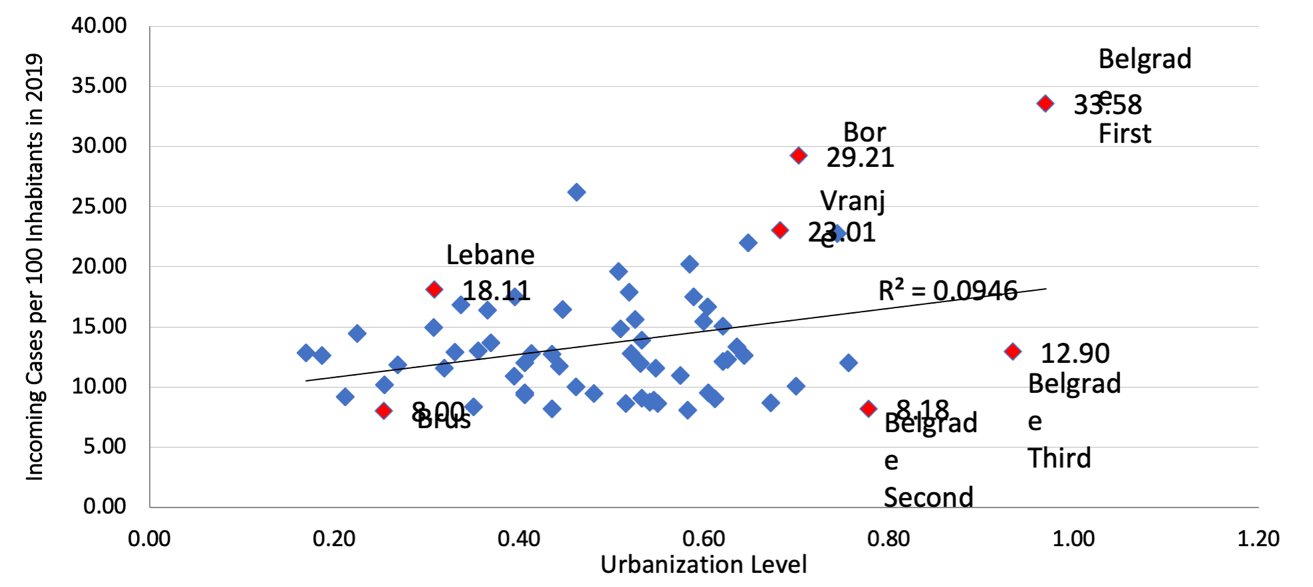

- Contrary to a view commonly heard in Serbia, there was no

firm correlation between court size and the burden posed by incoming

cases - some areas covered by smaller courts had relatively higher

caseloads than courts of the same types in larger cities. The

misconception that courts in capitals and regional centers faced

significantly higher demand was very typical among those interviewed by

the FR team, mostly because of the higher absolute number of cases in

the larger courts. Figure 18 demonstrates the lack of correlation

between urbanization levels and per capita caseload regardless of the

available number of judges. Caseloads per judge are analyzed in the

following section.

Figure 18: Basic Courts – Incoming Cases per 100 Inhabitants in 2019

vs. Urbanization Level

Source: SCC Data, Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia

and WB Calculations

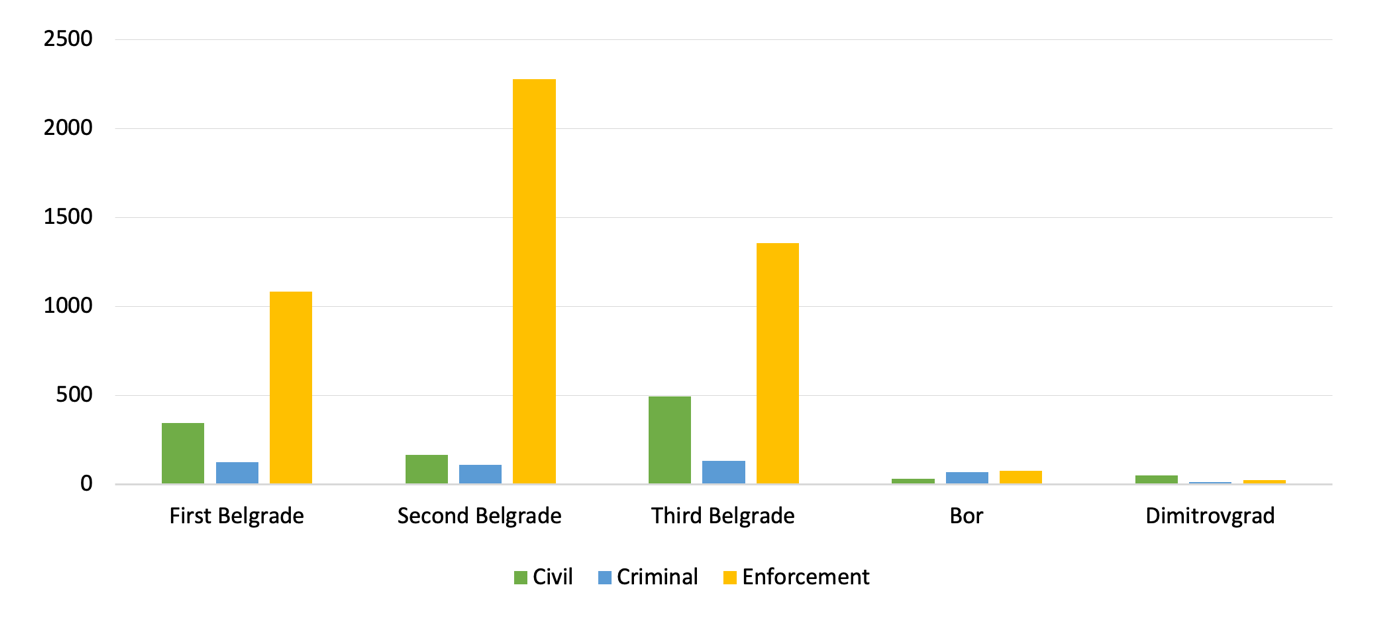

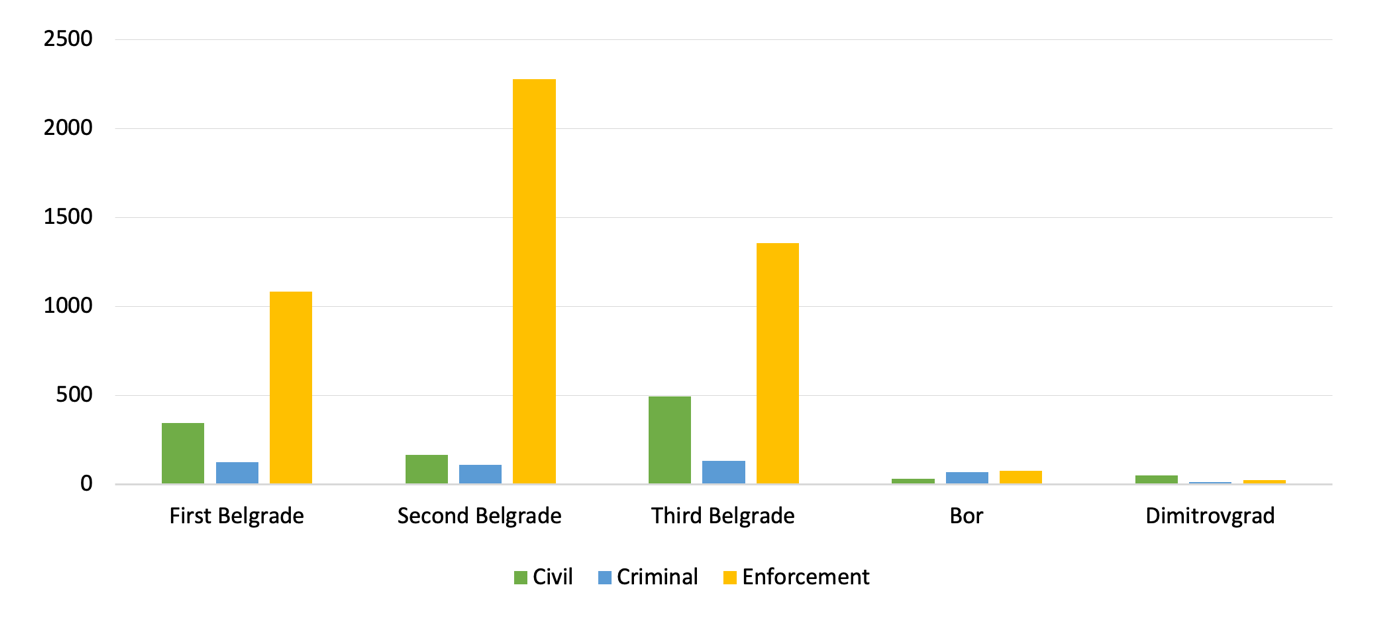

- Of all Belgrade’s courts, only its First Basic Court and

Higher Court were the highest among their peers in terms of received

cases per 100 inhabitants. The Second and the Third Basic

Courts were 62nd and 28th, respectively. As for

the Appellate, Misdemeanor and Commercial

Courts, Belgrade’s courts were second.

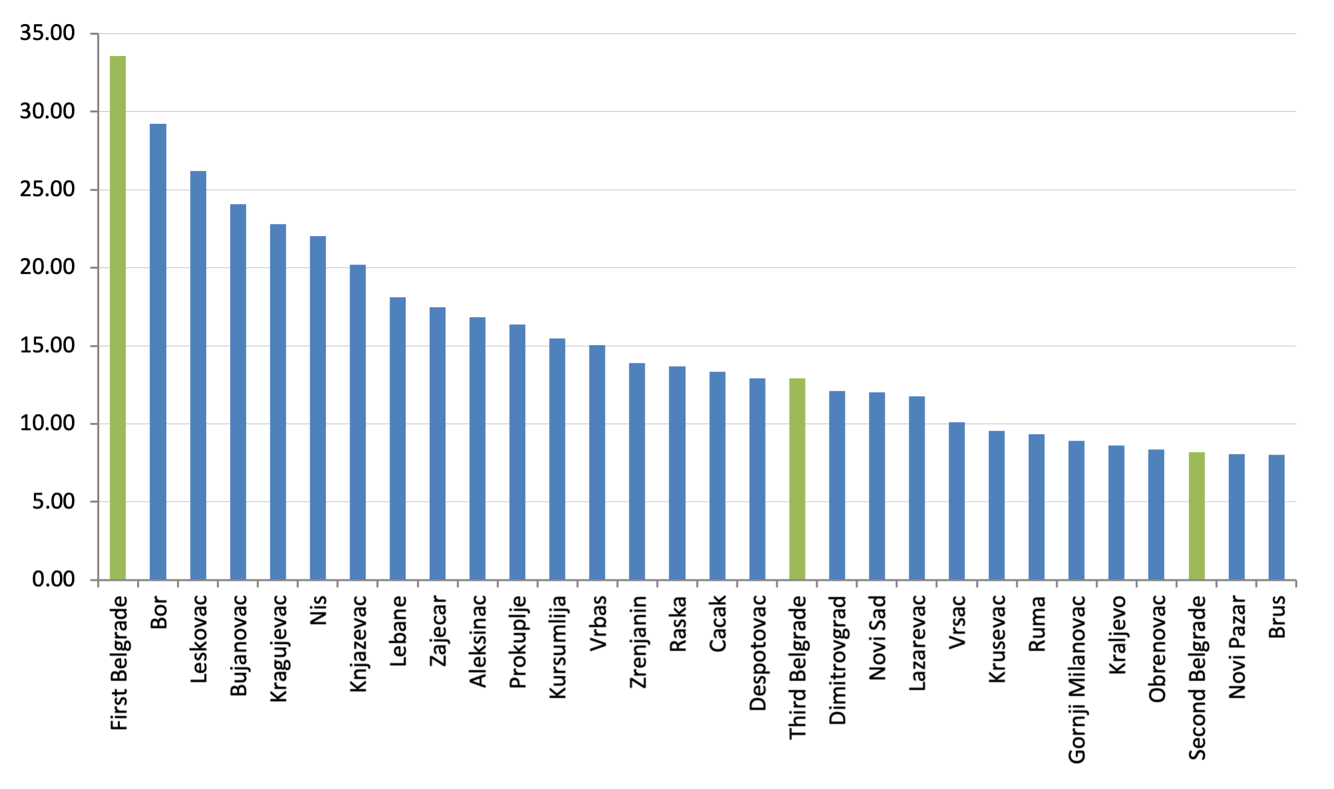

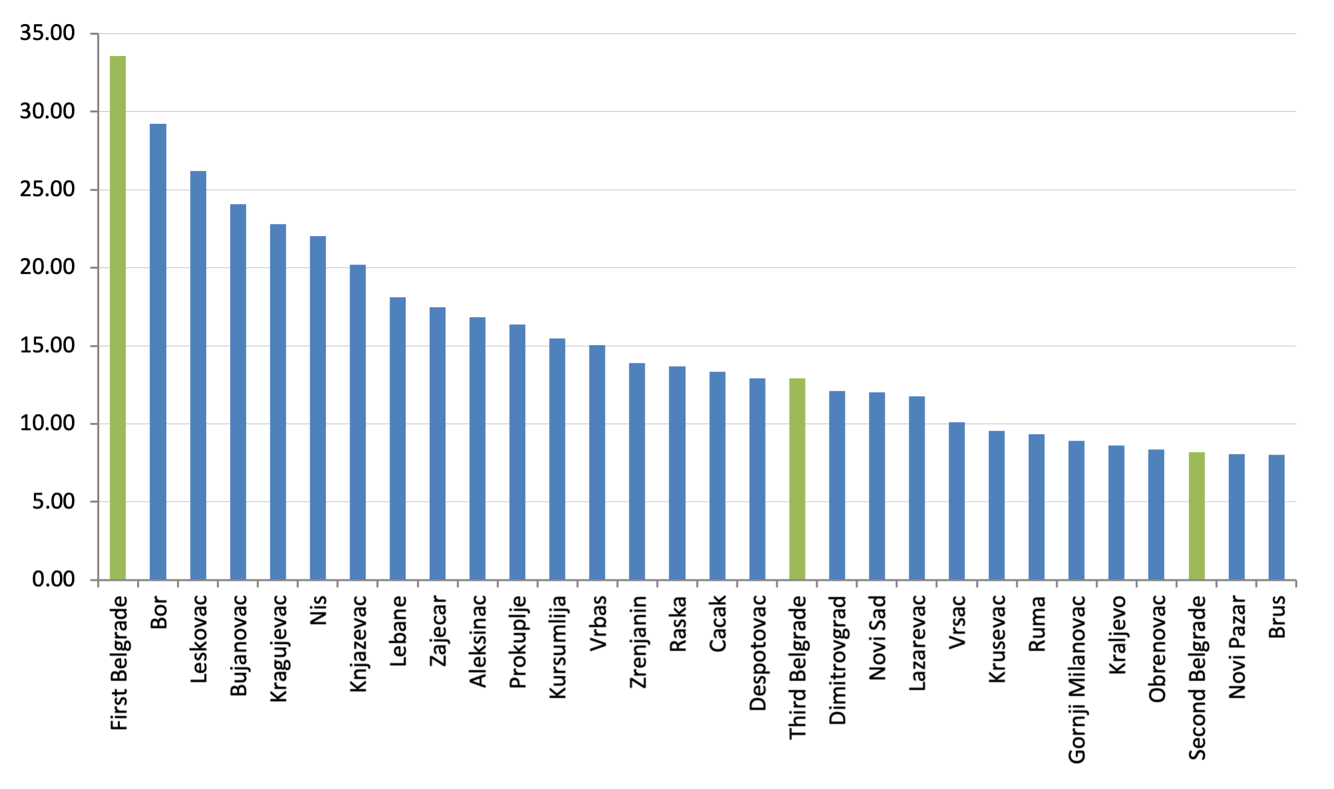

- The highest caseload per 100 inhabitants in 2019 was

recorded in the First Basic Court in Belgrade – 33.58 incoming cases per

100 inhabitants. Interestingly, the second-highest demand at

29.21 incoming cases per 100 inhabitants was recorded in Basic Court in

Bor, which covered only one-tenth of the population covered by the First

Basic Court in Belgrade. Examples of smaller courts with higher

caseloads were found in other court types as well. In Figure 19 below,

Belgrade’s courts are displayed in green.

Figure 19: Incoming Cases in Selected

Basic Courts per 100 Inhabitants in 2019

Source: SCC Data and WB Calculations

Caseloads per Judge ↩︎

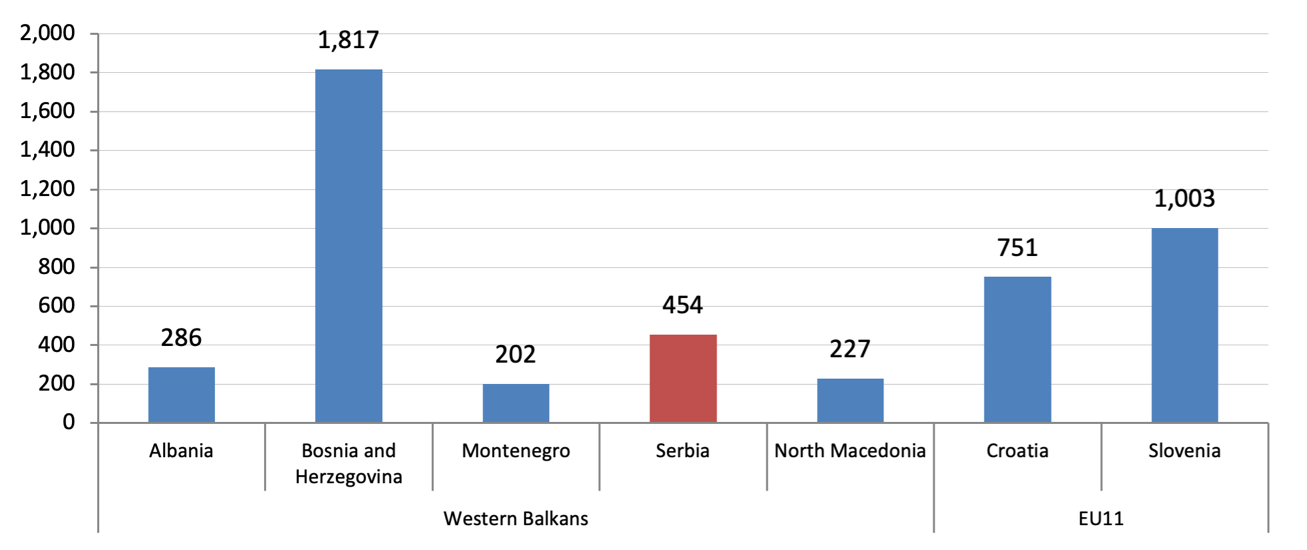

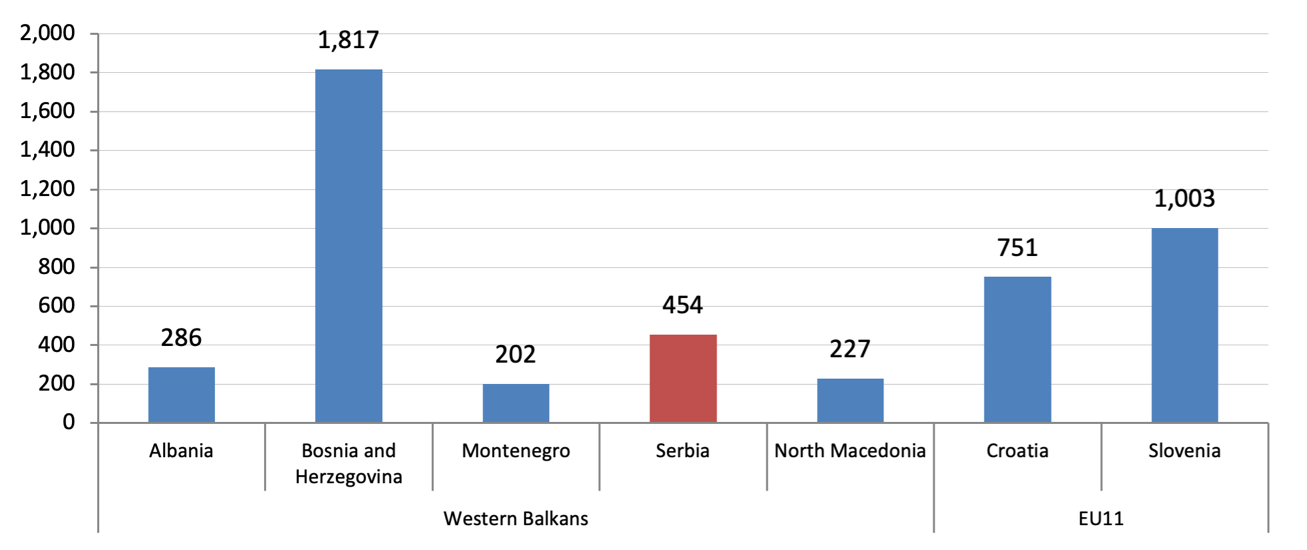

- CEPEJ data reveal that

Serbia’s average number of incoming, non-criminal first-instance cases

per judge was lower than of some of Serbia’s Western Balkans and EU11

regional peers. Incoming caseload per judge is measured by

dividing the number of received cases by the number of judges. As

displayed in Figure 20, judges from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia,

and Croatia received several times more cases than Serbian judges. These

countries usually serve as appropriate comparisons to Serbia because

their similar legal traditions, but that may not be as true for

caseloads since legislative reforms have changed the jurisdictions of

courts in these countries over time. For example, both Croatia and

Slovenia count land registry and company registry cases as non-criminal

cases (although most of the work on these matters is entrusted to the

courts’ administrative staff), while in Serbia, these matters are

handled by specialized agencies rather than courts. In addition, some of

the peer countries’ enforcement cases have remained in the courts to a

much greater extent than they have in Serbia.

Figure 20: Non-Criminal Caseload per Judge in Selected Countries in

2018

Source: CEPEJ 2020 Report (2018 Data)

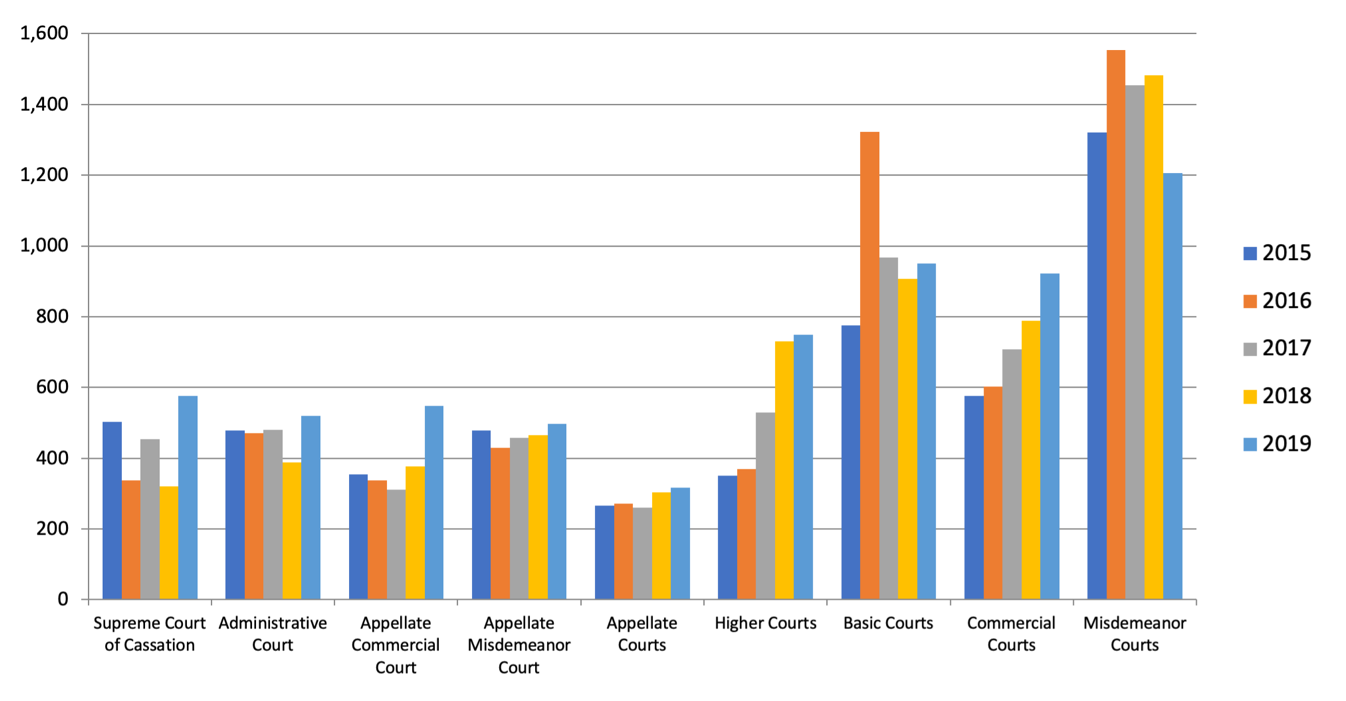

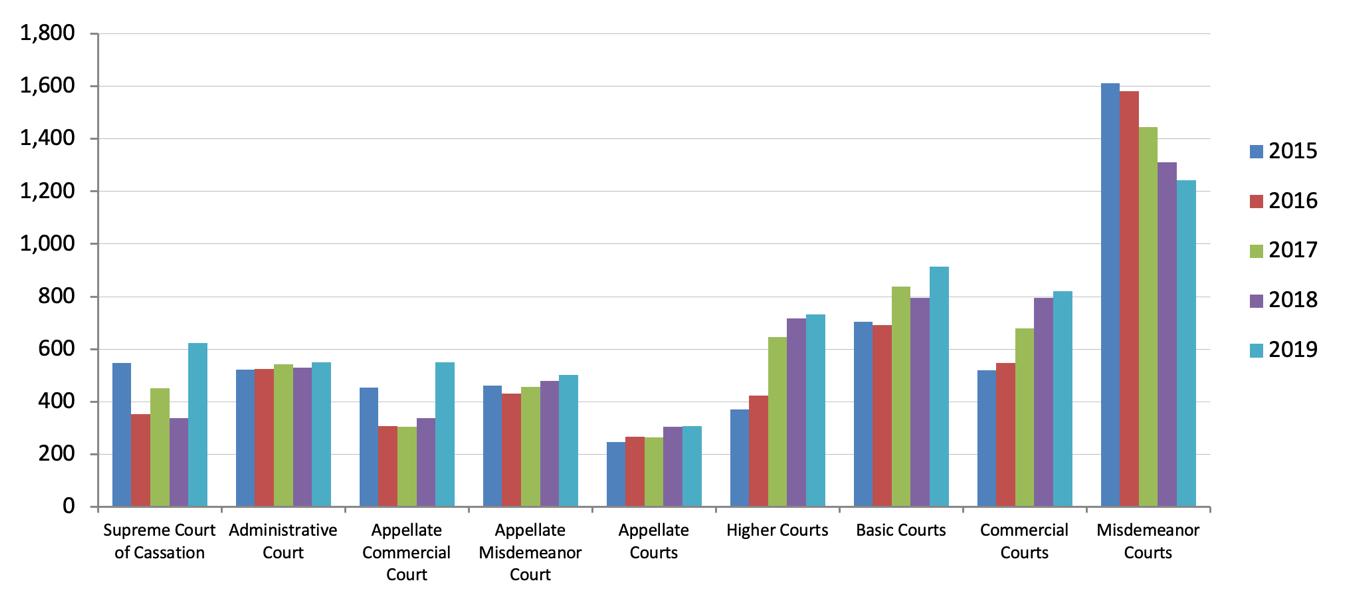

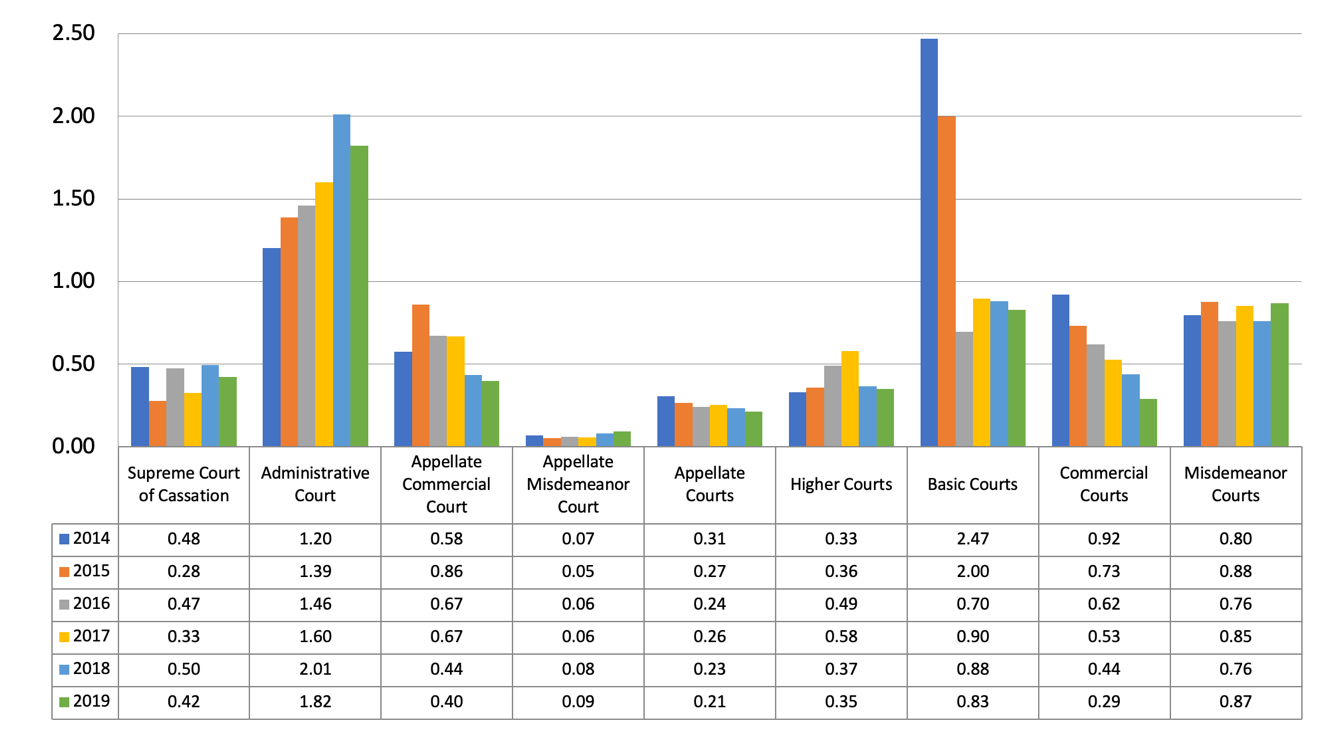

- Incoming caseloads per judge varied in Serbia across

court types from 2015 to

2019. They increased consistently only in the Higher and

Commercial Courts. In contrast, there was a persistent decline among

Misdemeanor Courts. For other court types, the caseload per judge varied

from year to year, as displayed in Figure 21 below.

Figure 21: Caseload per Judge by Court Type from 2015 to 2019

Source: SCC Data and WB Calculations

- The caseload per judge in Misdemeanor Courts in 2015 was

the largest caseload covered by this FR, at 1,611. Misdemeanor

Courts’ caseload per judge decreased after that due to a combination of

falling incoming cases and an increasing number of filled judge

positions. What had been a relatively stable rate of around 450 incoming

cases per judge for the Appellate Misdemeanor Court started increasing

in 2018: it reached 479 in 2018 and 503 in 2019.

- In Basic Courts, the average caseload per judge in 2019

was 914 cases; however, there were substantial differences among

individual courts that did not correspond to their size, as shown in

Table 4 below. The 2019 caseload per judge grew by 15 percent

compared to 2014, due to increased civil and enforcement cases and a

slight reduction in the number of sitting judges. Of the 66 courts

analyzed below, only 15 percent were within average values while 38

percent were above average and 47 percent below average.

Table 4: Average Caseloads per Judge in Basic Courts in 2019

| Lebane |

7,342 |

5 |

1,468 |

Vranje |

20,387 |

26 |

784 |

| Third Belgrade |

55,039 |

38 |

1,448 |

Obrenovac |

6,076 |

8 |

760 |

| Aleksinac |

12,951 |

9 |

1,439 |

Despotovac |

6,040 |

8 |

755 |

| Leskovac |

46,026 |

33 |

1,395 |

Backa Palanka |

6,599 |

9 |

733 |

| First Belgrade |

157,551 |

115 |

1,370 |

Mladenovac |

10,256 |

14 |

733 |

| Pozega |

10,596 |

8 |

1,325 |

Cacak |

15,364 |

21 |

732 |

| Knjazevac |

6,361 |

5 |

1,272 |

Senta |

5,702 |

8 |

713 |

| Sombor |

21,497 |

18 |

1,194 |

Novi Pazar |

10,624 |

15 |

708 |

| Bor |

14,201 |

12 |

1,183 |

Lazarevac |

6,895 |

10 |

690 |

| Subotica |

23,608 |

20 |

1,180 |

Brus |

3,428 |

5 |

686 |

| Uzice |

19,783 |

17 |

1,164 |

Mionica |

3,417 |

5 |

683 |

| Sremska Mitrovica |

10,210 |

9 |

1,134 |

Ub |

4,086 |

6 |

681 |

| Kragujevac |

48,599 |

43 |

1,130 |

Prokuplje |

12,244 |

18 |

680 |

| Loznica |

14,616 |

14 |

1,044 |

Raska |

3,373 |

5 |

675 |

| Nis |

66,349 |

64 |

1,037 |

Zajecar |

12,669 |

19 |

667 |

| Vrbas |

15,288 |

15 |

1,019 |

Ruma |

7,937 |

12 |

661 |

| Zrenjanin |

21,324 |

21 |

1,015 |

Gornji Milanovac |

3,958 |

6 |

660 |

| Kraljevo |

13,189 |

13 |

1,015 |

Pancevo |

16,197 |

25 |

648 |

| Kikinda |

11,065 |

11 |

1,006 |

Paracin |

13,267 |

21 |

632 |

| Prijepolje |

6,855 |

7 |

979 |

Vrsac |

8,145 |

13 |

627 |

| Velika Plana |

11,632 |

12 |

969 |

Surdulica |

8,109 |

13 |

624 |

| Second Belgrade |

43,519 |

45 |

967 |

Stara Pazova |

12,334 |

20 |

617 |

| Kursumlija |

4,787 |

5 |

957 |

Ivanjica |

6,107 |

10 |

611 |

| Veliko Gradiste |

3,753 |

4 |

938 |

Krusevac |

14,889 |

25 |

596 |

| Trstenik |

5,596 |

6 |

933 |

Novi Sad |

54,029 |

92 |

587 |

| Sabac |

26,233 |

29 |

905 |

Bujanovac |

5,087 |

10 |

509 |

| Pozarevac |

22,290 |

25 |

892 |

Negotin |

5,793 |

12 |

483 |

| Pirot |

10,127 |

12 |

844 |

Sjenica |

2,398 |

5 |

480 |

| Becej |

5,848 |

7 |

835 |

Priboj |

2,344 |

5 |

469 |

| Jagodina |

14,816 |

18 |

823 |

Sid |

2,789 |

6 |

465 |

| Smederevo |

16,395 |

20 |

820 |

Valjevo |

11,284 |

27 |

418 |

| Petrovac on Mlava |

5,641 |

7 |

806 |

Majdanpek |

1,629 |

5 |

326 |

| Arandjelovac |

9,636 |

12 |

803 |

Dimitrovgrad |

1,226 |

5 |

245 |

Source: SCC Data and WB Calculation

Box 8: Impact of the Reappointment of Judges and the Past Reform of

the Court Network

Workloads ↩︎

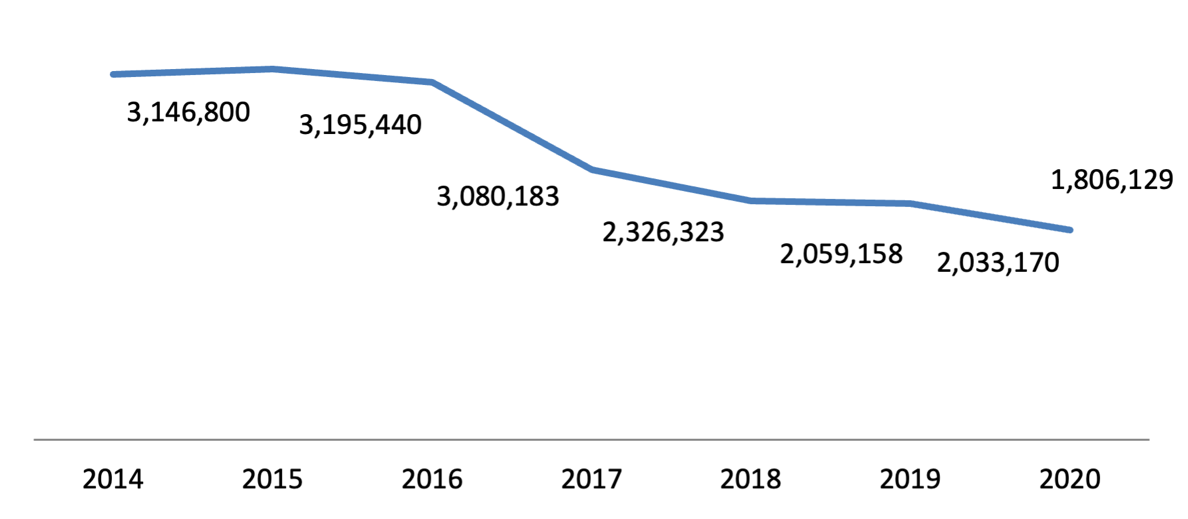

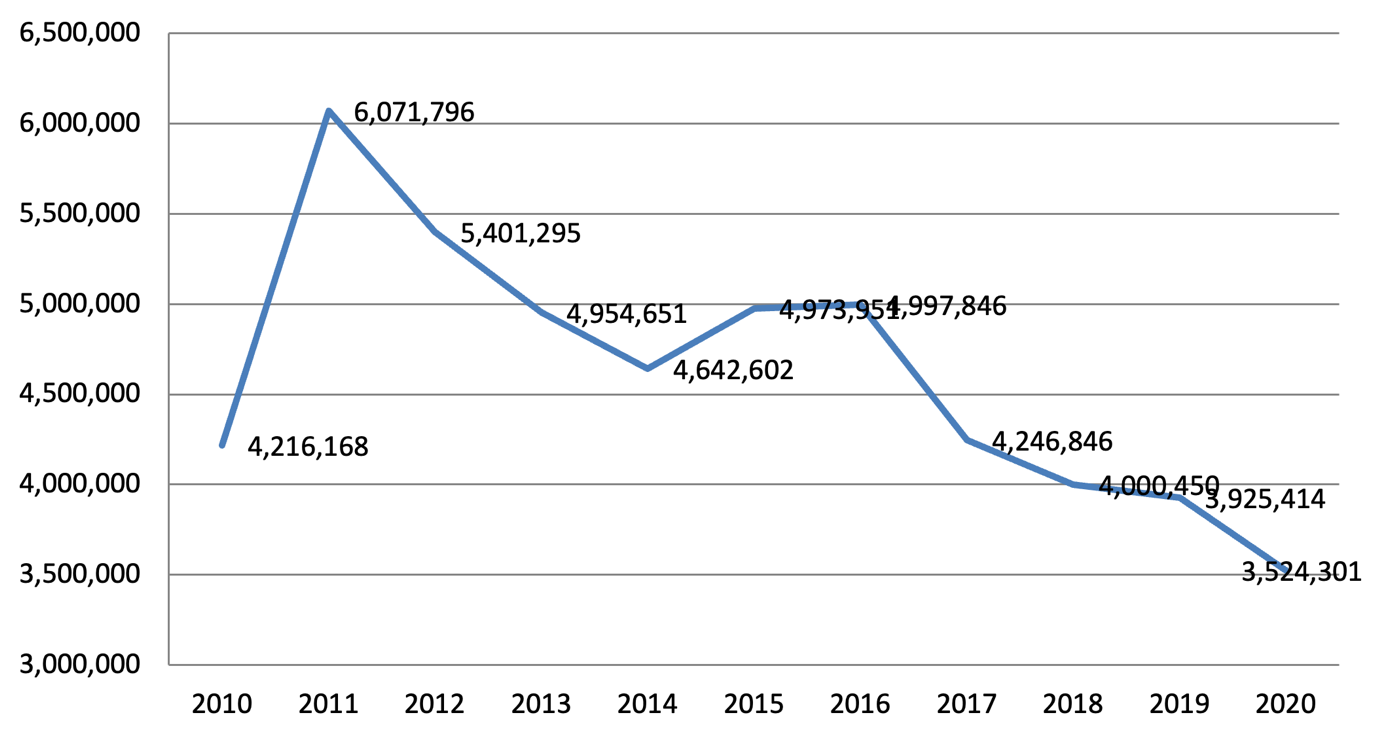

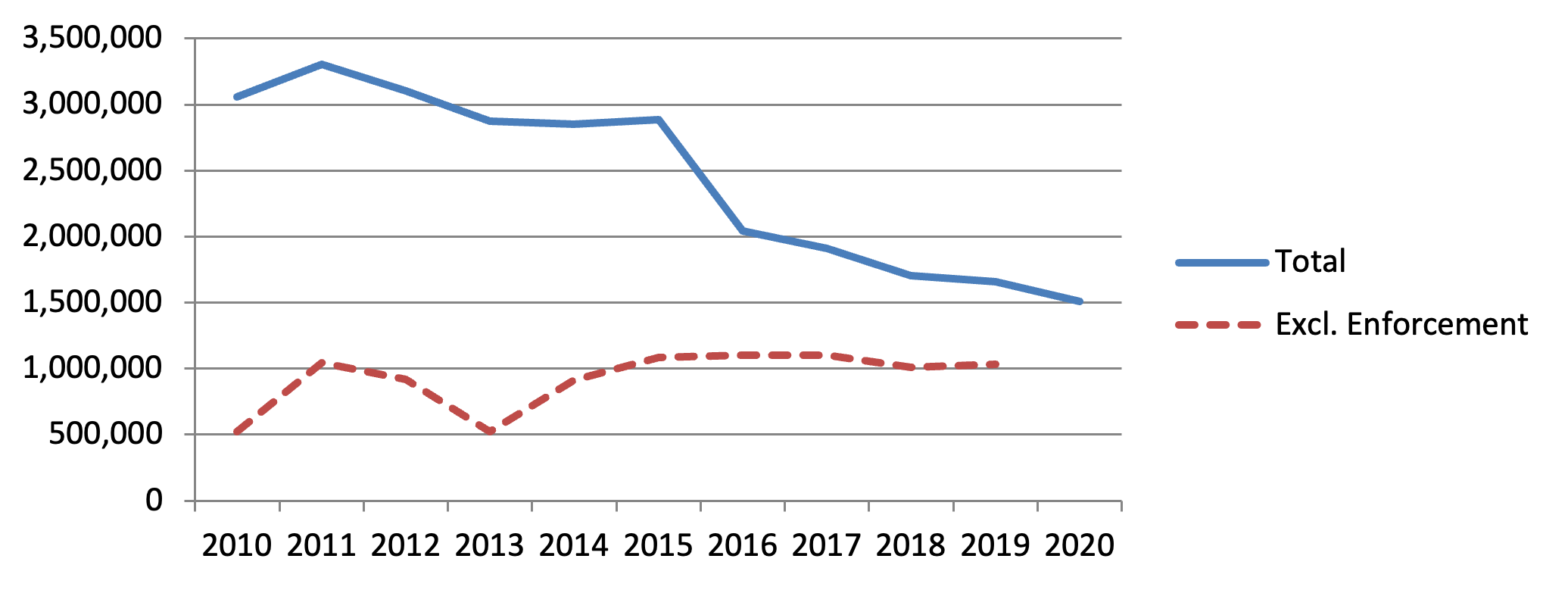

- Overall court workloads, defined as the sum of received

cases and carried-over cases from previous years, as noted above,

declined by seven percent in Serbia from 2010 to 2019. In 2014 the workload comprised

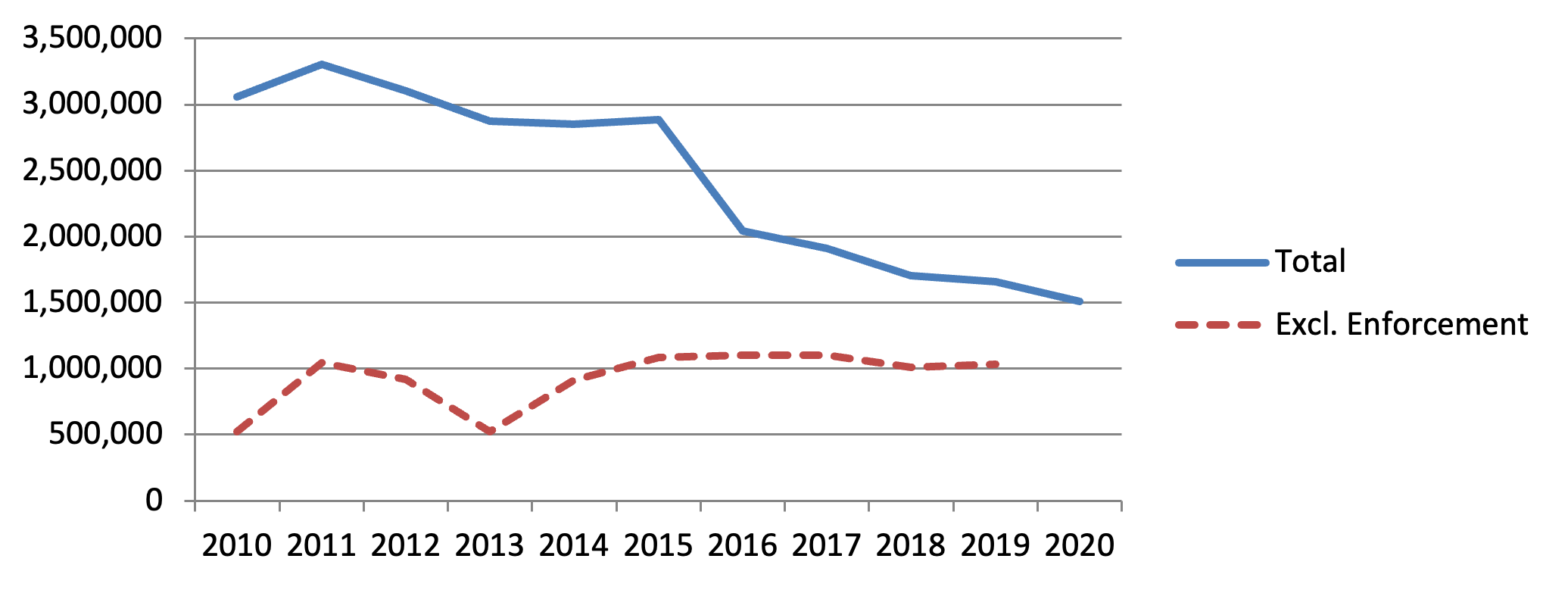

4,642,602 cases, 3,925,414 cases were handled in courts in 2019, while

3,524,301 cases were pending in 2020. See Figure 22.

Figure 22: Workloads in Serbian courts from 2010 to 2020

Source: SCC Data

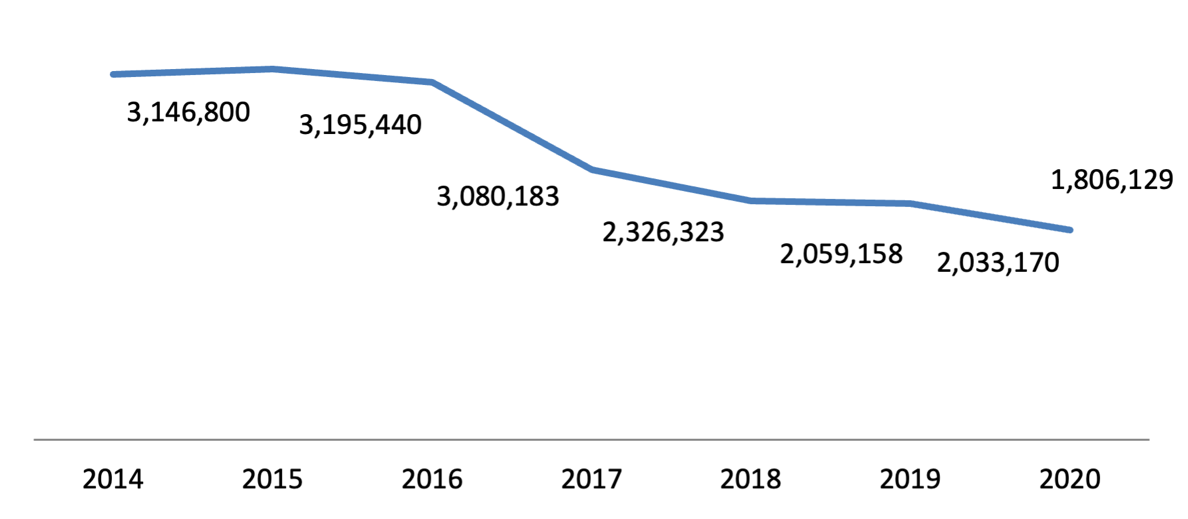

- Fifty-two percent of the total court workload in 2019

consisted of Basic Court cases. Basic Courts’ workload

decreased by 35 percent from 2014, i.e., there were more than 1 million

pending cases fewer in 2019. As discussed elsewhere in this FR, the

reduction was caused primarily by falling enforcement workloads in Basic

Courts. In 2020, the workload of Basic Courts fell further, by 11

percent, to 1,806,129 cases. See Figure 23.

Figure 23: Workloads in Basic Courts from 2014 to 2020

Source: SCC Dana

- Workloads of Higher Courts more than doubled from 2014 to

2019, from 145,345 cases to 344,205. The numbers increased each

year except 2019, but the most drastic increases occurred in 2017 and

2018, by 47 and 30 percent, respectively.

- All other types of court workloads also increased from

2014 to 2019, except for the Appellate Misdemeanor Court and the

Appellate Courts. The Appellate Misdemeanor Court and the

Appellate Courts reduced their workloads by 22 and 12 percent,

respectively.

Efficiency in

the Delivery of Justice Services ↩︎

Chapter Summary

- From 2014 to 2019, the productivity in Serbian courts

improved in many areas, but there were still domains that needed

considerable attention. Most clearance rates were over 100

percent due to the increase in dispositions, and implementation of

reforms that transferred enforcement cases to private bailiffs and

probate cases to public notaries. However, ‘bulk’ dispositions of

enforcement cases made the largest contributions to the favorable

clearance rates and without them, the improvements would not have been

as remarkable.

- As noted in the previous section, delegated cases

inflated the number of cases nationally. These appeared in the

statistics both as cases being disposed of in the originating courts and

as cases registered in the courts receiving them. The total number of

delegations were seen in SCC’s reports but individual court reports did

not report how many cases were delegated from or to that court.

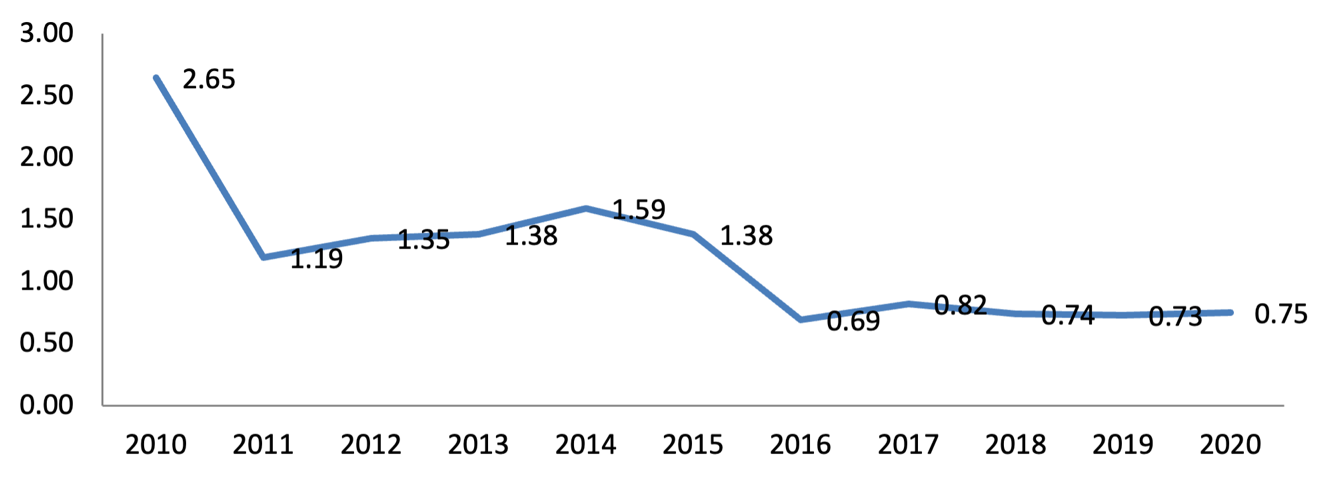

- The timeliness of case processing, measured through the

CEPEJ disposition time indicator, continually improved from 2014 to

2019, but with remarkable variations by case and court

type. The total disposition time for Serbian courts decreased

from 580 days in 2014 to 267 days in 2019 and the total congestion ratio

of courts in Serbia improved considerably, dropping to 0.73 in 2019. The pending stock was reduced by

more than 40 percent from 2014 to 2018, or from 2,849,360 cases at the

end of 2014 to 1,656,645 cases at the end of 2019. In 2020, the total

disposition time reached 274 days, the congestion ratio decreased

slightly to 0.75, while the courts ended the year with 1,510,472

unresolved cases.

- The National Backlog Reduction Programme that started in

2014 markedly reduced the massive backlogs in Serbian courts even if it

did not reach its stated goals.

At the outset, the goal was to reduce the backlog to 355,000 cases by

the end of 2018, from 1.7 million at the end of 2013. However, 781,000

backlogged cases were still pending at the end of 2018. The strategy was

amended in 2016 to include a goal of approximately 350,000 backlogged

cases for the end of 2020, which was not met, according to the

SCC.

- There was significant progress in reducing the courts’

backlogs of enforcement cases, but it was not clear how effective

private bailiffs had been in cases that had started as enforcement cases

in the courts. The congestion ratio of enforcement cases in

Basic Courts improved from 4.88 in 2014 to 1.47 in 2019, but many old

enforcement cases were still in the courts as of 2019, the last year for

which comparable data was available as of early 2021. The lack of

genuinely effective and timely enforcement, particularly for cases

arising in large courts, remained one of the biggest challenges for the

Serbian court system.

- The transfer of administrative tasks and probate cases to

public notaries significantly reduced the work of many judges, although

the transferred probate cases were still included in statistics about

court caseloads, workloads, and dispositions. In 2013, Basic

Courts received and resolved more than 700,000 verification cases,

compared to roughly 110,000 in 2019. Also In 2019, 91 percent of the

134,226 newly filed probate cases were transferred to public notaries,

which was an increase of 38 percentage points from 2018. Although the

transferred probate cases were still included in court statistics,

courts had little or no work to do with them once they were

transferred.

- Meanwhile, court performance was intensely constrained by

court management and organization, practice and procedure, and party

discipline. Service of process has improved lately, but

avoiding it is still quite easy. Party discipline is still widely

recognized as one of the main impediments of procedural efficiency.

Scheduling of hearings, the number of hearings per case, the timeliness

of their scheduling, and the frequency of cancellations and adjournments

hinder the efficiency of courts and cause lengthy trials. The advantages

of ICT tools are recognized but still not adequately utilized.

Production and

Productivity of Courts ↩︎

- The terms ‘production’ and ‘productivity’ are based on

the indicators of clearance rates, total dispositions, and dispositions

per judge. These indicators are actionable, meaning they can be

used as the bases for various measures to improve court efficiency. They

also enable objective comparison between and among different courts and

court types. Each indicator is described in more detail below.

Clearance Rates

- Clearance rates, which measure the number of resolved

cases as a percentage of the number of incoming cases, are among the

most commonly used indicators to monitor court performance both inside

and outside of Europe. A clearance rate indicates whether the

court is keeping up with its caseload or generating pending stock. A

clearance rate below 100 percent indicates that pending stock is being

generated, while a clearance rate of over 100 percent suggests that the

it is being reduced.

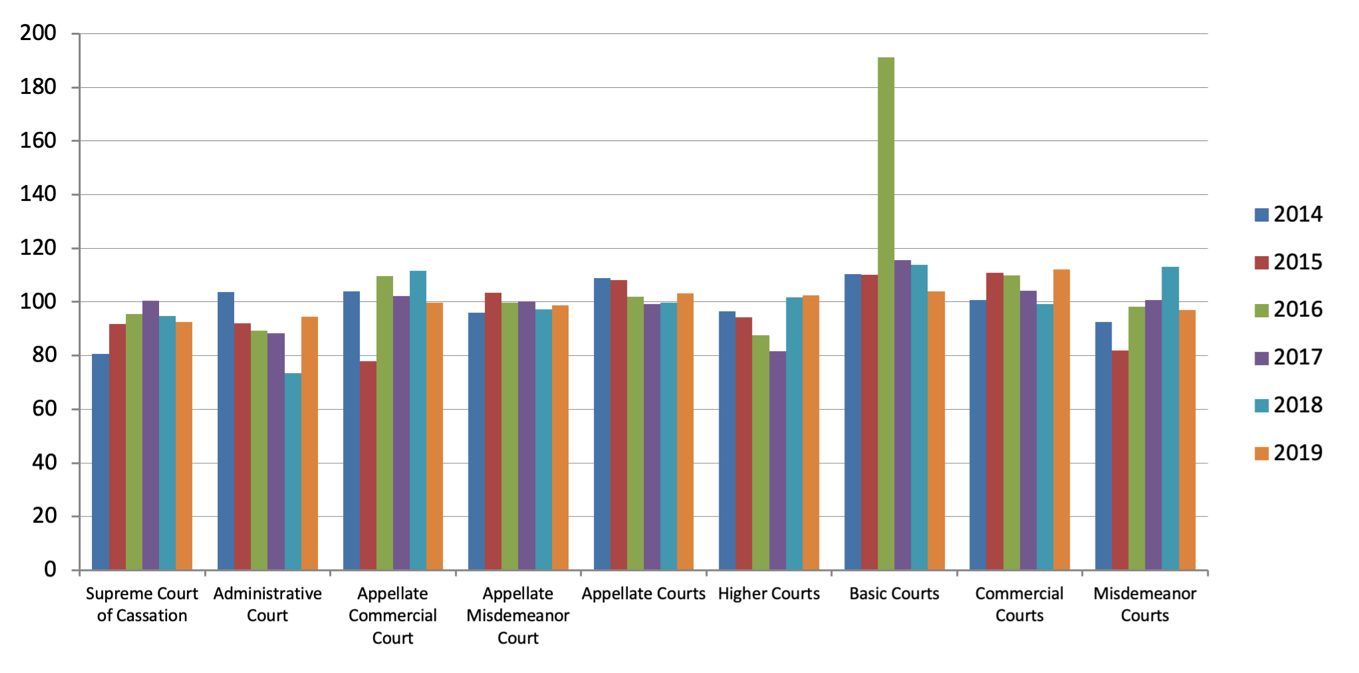

- The combined clearance rate for all courts in Serbia from

2014 to 2019 remained at over 100 percent, although it temporarily

decreased to 98 percent in 2015. The most exceptional year

during the period was 2016, when numerous enforcement cases were

dismissed, as noted above, and as a result, the overall clearance rate

for 2016 was 140 percent. In 2017, the combined rate was still over 100,

at 106 percent, while in 2020, it reached 108 percent.

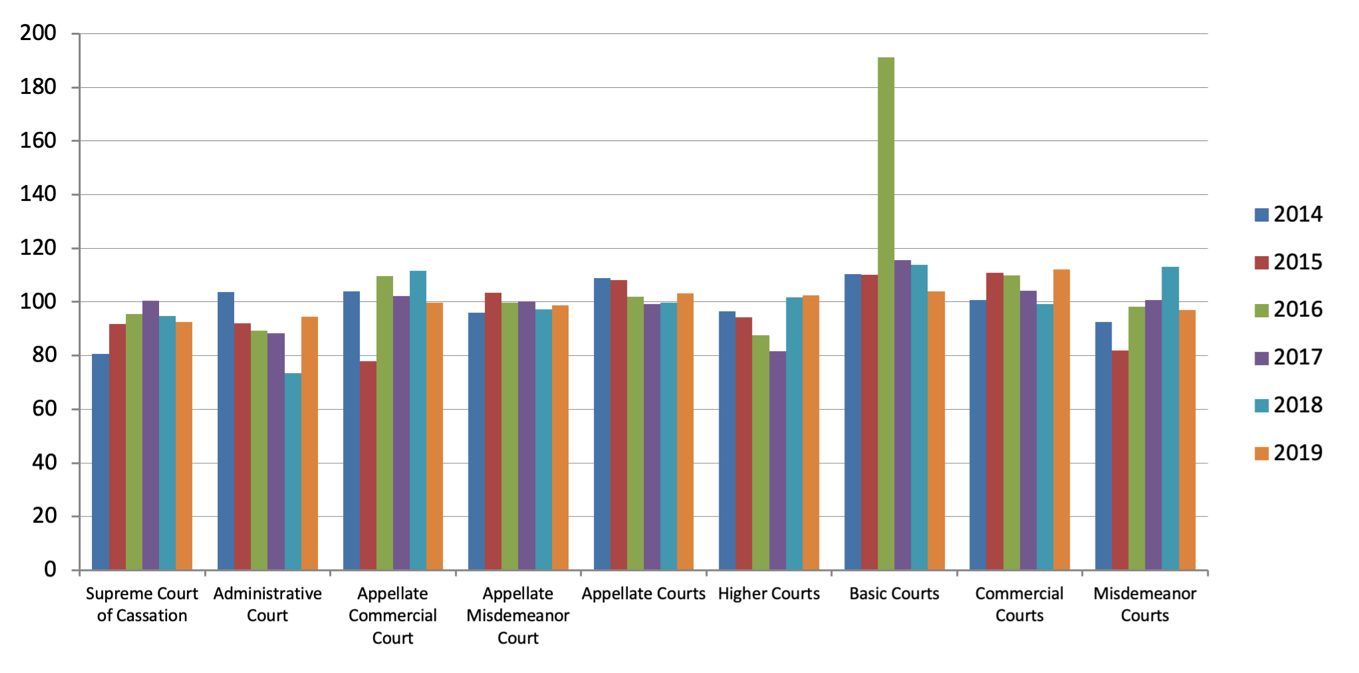

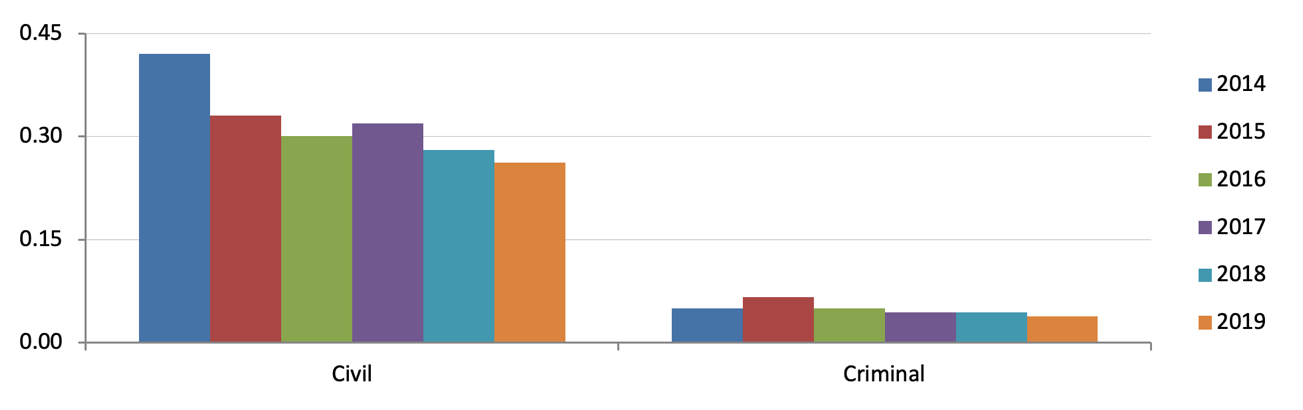

Figure 24:Clearance Rates by Court Types from 2014 to 2019

Source: SCC Data and WB Calculations

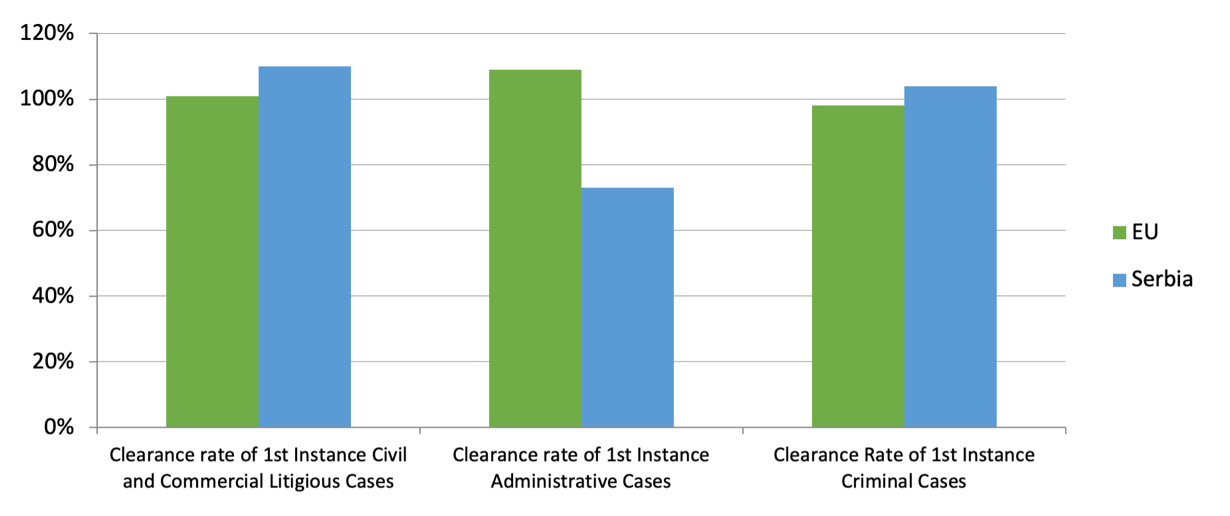

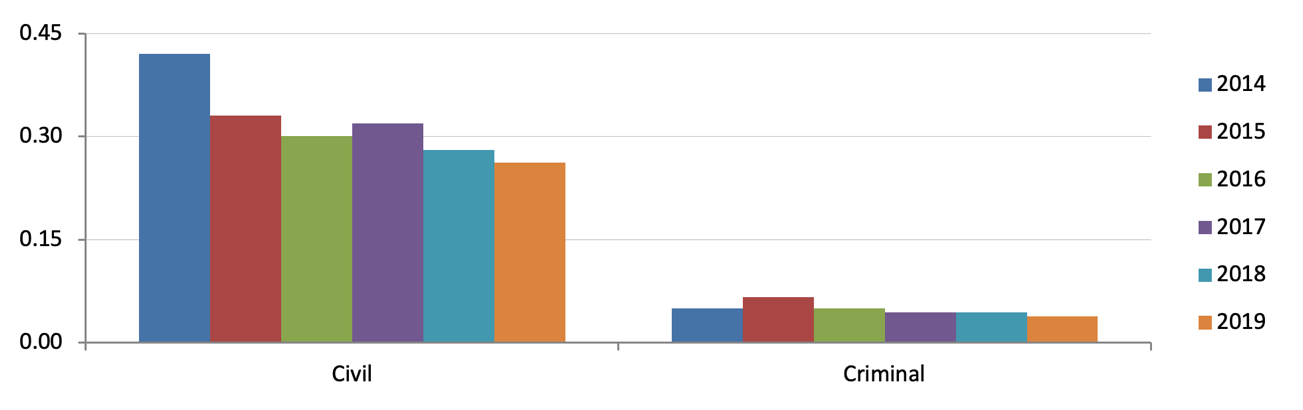

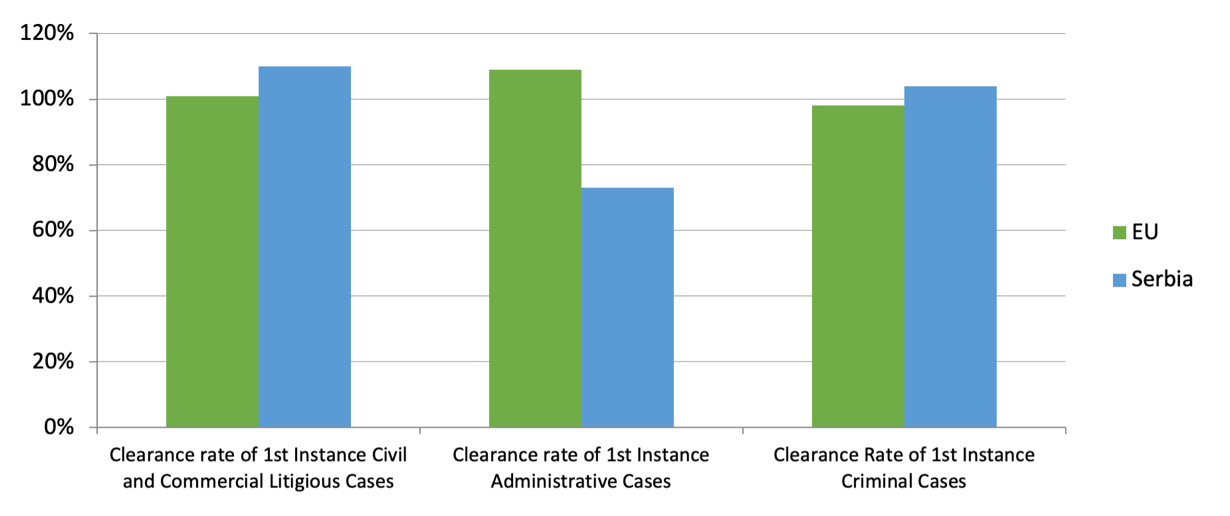

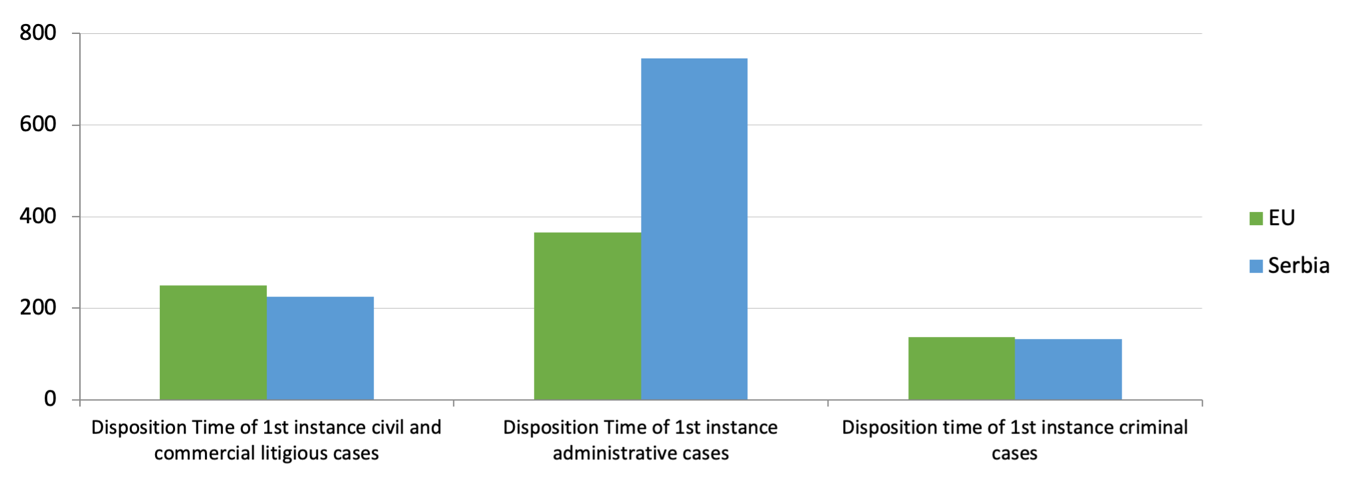

- Except for administrative cases, Serbia’s clearance rates

for first-instance cases in 2018 exceeded those of EU courts, according

to the CEPEJ 2020 Report. In 2018, Serbia’s

clearance rate of 73 percent for administrative matters was 36

percentage points lower than the rate for cases in the EU. In civil and

litigious commercial cases, Serbia achieved an overall clearance rate of

110 percent, as opposed to the EU average of 101 percent. Serbia’s

clearance rate for criminal cases was 104 percent, six percentage points

higher than the EU average. Compared to the CEPEJ evaluation cycle that

examined data from 2016, these results represented an improvement in the

civil, commercial, and criminal domains but a decline for administrative

cases. However, available data was not enough to explain the variations

in clearance rates among courts within the same categories, which

underlines the need for individual courts and the SCC to conduct and

publish more analyses of the reasons for the often extreme differences

in court productivity.

Figure 25: Clearance Rates of 1st Instance Cases According to CEPEJ

2020 Report (2018 data)

Source: CEPEJ Report 2020

- Overall clearance rates of Serbia’s Basic Courts from

2014 to 2019 were well above 100 percent; even more impressively,

starting in 2017 the results show the Basic Courts owed their favorable

clearance rates to results achieved in non-enforcement civil and

criminal cases, rather than the dismissal of backlogged enforcement

cases. Dismissal of enforcement cases was the primary factor in

the positive clearance rates from 2014 through 2016. Setting enforcement

cases aside, Basic Courts resolved fewer civil cases than they received

in 2014 and 2015, while the calculated clearance rate for 2016 was 101

percent. The Basic Court overall rates were

110 percent in 2014 and 2015, 191 percent in 2016, 116 percent in 2017,

114 percent in 2018 and 104 percent in 2019.

- Clearance rates of many individual Basic Courts were

close to or higher than 100 percent but with substantial variations even

among courts of similar size and/or urban setting. For example,

the First Basic Court in Belgrade achieved 92 percent in 2014, while in

2015, this rose to 123 percent. The unfavorable clearance rate of the

First Basic Court in Belgrade in 2014 probably was due in large part to

the reorganization of the court network (see Box 8). Unsurprisingly, the

influence of enforcement dismissals was considerable in this court,

causing extremely high clearance rates in 2016 (470 percent) and 2017

(295 percent). In contrast, both the Second and Third Basic Courts in

Belgrade had positive clearance rates in 2016, but in 2017 this changed

dramatically solely because of the high number of enforcement cases

transferred to them from the First Basic Court in Belgrade: this was

done, at least in part, to align the distribution of these cases with

the territorial limits of those courts. For 2017, the Second Basic Court

reported a clearance rate of 39 percent, while the Third Basic Court’s

clearance rate was only 34 percent. In 2018, clearance rates recovered

to 127 percent for the Second Basic Court and 99 percent for the Third.

While much of this improvement was due to the dismissal or transfer to

private bailiffs of many of the transferred enforcement cases, there

were improvements in clearance rates for other types of cases as

well.

- Thirteen Basic Courts

of varying sizes and locations did not achieve 100 percent clearance

rates in 2019. However, half of these ‘underperformers’ were

very close to 100 percent, with clearance rates of 97 percent or higher.

The lowest clearance rate among them was that of the Basic Court in

Leskovac at 88 percent, which was caused by the combination of an

increased incoming caseload mainly of civil litigious cases and a 13

percent reduction in the number of judges at the Court compared to 2015

and 2016.

Figure 26: Clearance Rates of Selected Basic Courts from 2014 to

2019

Source: SCC Data and WB Calculations

- The Higher Courts’ clearance rates were relatively low

and decreased from 2014 to 2017, but the overall results increased

rapidly in 2018 and 2019, when their combined rate was 102

percent. In 2017 only the Higher Court in Prokuplje managed to

reach a clearance rate above 100 percent (at 101 percent). All other

courts were well below 100 percent, even down to 66 percent in the

Higher Courts in Kragujevac and Pirot. In 2018 the variations were

particularly extreme -- from 70 percent in Kragujevac to 172 percent in

Krusevac. In 2019, 68 percent of Higher Courts had clearance rates of

100 percent or more, but the SCC did not release any analysis that

accounted for the more uniform results, if one was done.

- From each year from 2014 to 2019, only the Higher Court

in Belgrade reported a clearance rate below 100 percent, while no single

Higher Court had a clearance rate of 100 percent or higher throughout

the period. In 2019, Higher Courts in Valjevo and Kragujevac

reversed a negative series of clearance rates that stretched back to

2014 by achieving 123 and 119 percent, respectively. Both of those

courts received fewer cases and disposed of more civil first-instance

cases in 2019 than in the previous years.

- The Appellate Courts’ overall clearance rate dropped from

109 percent in 2014 to 99 percent in 2017 and then increased to 103

percent in 2019. In 2019, each of the four Appellate Courts

produced favorable results with clearance rates equal to or over 100

percent: 106 percent in Belgrade, 103 percent in Kragujevac and Nis, and

100 percent in Novi Sad.

- Clearance rates for the Misdemeanor Courts varied widely

from 2014-2019, and not all of the reasons for the variations were clear

from available data. There also was no available information

from the judiciary about the cause of the fluctuations. From 2014 to

2018 Misdemeanor Courts improved their overall clearance rate to 113

percent, but it dropped it to 97 percent in 2019, without any apparent

regard to the number of judges in the courts. The number of judges in

Misdemeanor Courts fell by 10 percent from 2015 to 2018, but the

remaining judges still resolved more cases each year and improved their

productivity during that period. In contrast, the number of judges then

increased by 12 percent in 2019, but dispositions decreased by nine

percent. The highest clearance rate in 2019 was produced by the

Misdemeanor Court in Vranje (126 percent), while the lowest was that of

the Misdemeanor Court in Sremska Mitrovica (74 percent). Of the 44

Misdemeanor Courts in Serbia, 30 of them, or 68 percent, achieved

clearance rates of 100 percent or higher in 2019, which was a reduction

of 19 percentage points compared to 2018.

- In 2019 the Appellate Misdemeanor Court clearance rate

improved by two percentage points compared to 2018 but was still

negative due to increased incoming caseloads in 2018 and 2019.

With a rate of 99 percent in 2019, the Court still did not manage to

match the positive rates it had from 2015 to 2107.

- Commercial Courts’ overall clearance rates varied between

100 to 110 percent, and the same generally was true of the Appellate

Commercial Court. The highest clearance rate of Commercial

Courts was 112 percent recorded in 2019. The lowest was 99 percent in

2018, a year when 44 percent of the Commercial Courts could not reach

the 100 percent clearance rate. These were Commercial Courts in

Belgrade, Kraljevo, Sombor, Valjevo, Sremska Mitrovica, Cacak, and

Leskovac (which had the lowest clearance rate of the group at 89

percent). In 2019, only the Commercial Court in Pancevo did not achieve

a clearance rate of 100 percent, and it came close at 98 percent. The

one-year drop in its clearance rate reported by the Appellate Commercial

Court in 2015 was caused primarily by a jump in incoming cases

(particularly claims involving the right to trial within a reasonable

time in bankruptcy cases), while the number of dispositions remained

unchanged.

- Clearance rates for the Administrative Court decreased

each year from 2014 (104 percent) to 2018 (73 percent): 2019 brought

signs of a limited recovery with a clearance rate of 94

percent. The declines in the clearance rates for the

Administrative Court were accompanied by the constant growth of the

Court’s pending cases. The addition of eight judges (one-fifth of the

total) in 2018 was not enough for the Court to deal effectively with the

increased number of cases and falling dispositions that year. In 2019,

the court lost seven judges, so the increased clearance rate for 2019

had to be due to the 11 percent decrease in incoming cases and a 14

percent increase in dispositions.

- The SCC significantly improved its clearance rate each

year from 2014 (81 percent) to 2017 (101 percent in 2017), but the rate

declined in 2018 (95 percent) and 2019 (92 percent), apparently due to

increased numbers of civil cases. The SCC reported its

declining clearance rates in 2018 and 2019 were due to “changes in

regulation on the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of Cassation,

reduction of the review threshold to EUR 40,000 € in RSD equivalent, the

introduction of a special revision as a new extraordinary legal remedy,

as well as the expansion of the jurisdiction of the highest court to

decide on the revision, i.e. to decide on the new extraordinary legal

remedies.”

Case Dispositions

- Many judicial systems use case dispositions - the total

number of cases resolved each year – as an indicator of court production

and productivity, but these statistics were inflated to some extent in

Serbia for the period under review. For purposes of this FR,

“dispositions” refer to the resolution of cases in a particular court.

As this chapter already has shown, many of Serbia’s reported

dispositions are not final resolutions because the case may have been

delegated or transferred, appealed or remanded to a lower court for

further proceedings. As an incoming case in the new court, those cases

would have received a new number, so the same legal matter may have had

several case numbers during its lifetime and be counted as a

“disposition” several times.

- Significant variations in dispositions may demonstrate

the need to reallocate resources, adjust targets or budget allocations,

and can be used to assess the effects of specific reforms. For

example, in Serbia, the number of case dispositions was heavily

influenced by the introduction of the Criminal Procedure Code 2013 (CPC)

with its transfer of investigative responsibilities from courts to

prosecutors in late 2013, and the introduction in 2012 of private

bailiffs for the enforcement of court decisions.

Both of these reforms enabled judges to reallocate their efforts to

other case types.

- In 2019 the SCC delegated approximately 6,200 cases from overburdened

courts. This intervention aimed to (ad

hoc) distribute cases more evenly among courts and thus facilitate

faster resolutions. In 2015, 2017 and 2019 this possibility was used to

a greater extent. Although this is not clear from

the available reports, considerably fewer resolved delegations

registered in other studied years is a result of conflicts of

jurisdiction cases reported under the same category.

There is no adequate mention of delegations in Serbian annual court

reports, and the criteria applied for it remained unknown for this

analysis. Yet, since data confirm that certain smaller courts tend to be

busier than the larger ones, it would be essential to consider that

factor while deciding on delegations.

- Variations in disposition numbers also were due in part

to factors that were exogenous to the judiciary, such as the attorney

strike in Belgrade of 2014-15 (see Box 9 below), and perhaps the rumored

tendency of some judges to concentrate on cases that are the most easily

resolved.

Box 9: The Attorney Strikes in 21st Century Serbia

- In 2019 Serbian courts reported the disposition of

2,268,769 cases, a 27 percent increase from 2014. As incoming caseloads

grew in the Misdemeanor, Basic, Higher and Appellate Commercial Courts,

as well as the SCC, so did their dispositions. Figure 27 below

displays variations in annual dispositions of Serbian courts from 2010

to 2019 and illustrates that, for the most part, the system reported

disposing of more cases than it received. The Basic Courts’ positive

results produced a major spike in 2011, which the FR2014 attributed to

the withdrawal of large numbers of cases involving unpaid utility bills,

and there were remarkable numbers of disposed of cases again from 2014

to 2016 (2016 being a prime year for the disposition of enforcement

cases). Dispositions started declining in 2017 with a 21 percent drop.

This was followed by a two percent drop in 2018, an additional one

percent drop in 2019, and an 11 percent drop in 2020.

Figure 27: Total Dispositions of Serbian Courts from 2010 to 2020

Source: SCC Data

- As shown in Table 5 and Figure 28 below, total annual

dispositions varied noticeably across court and case types, with the

Basic and Misdemeanor Courts having the strongest influence on the

overall numbers. Dispositions consistently increased only in

Commercial Courts. The previously impressive improvements in the Higher

Courts ended in 2019, with a decline of two percent.

Table 5: Total Dispositions by Court Type and Case Type from 2014 to

2019

| Basic Courts |

906,843 |

1,065,071 |

17percent |

1,815,045 |

70percent |

1,226,428 |

-32percent |

1,093,219 |

-11percent |

1,110,393 |

2percent |

| Civil Litigious Cases |

186,372 |

263,288 |

41percent |

279,302 |

6percent |

257,627 |

-8percent |

249,228 |

-3percent |

245,459 |

-2percent |

| Civil Non-Litigious Cases |

187,032 |

219,321 |

17percent |

234,560 |

7percent |

249,897 |

7percent |

270,444 |

8percent |

290,623 |

7percent |

| Criminal Investigation |

4,046 |

1,056 |

-74percent |

520 |

-51percent |

213 |

-59percent |

136 |

-36percent |

90 |

-34percent |

| Criminal (Other than Investigation) |

132,569 |

136,622 |

3percent |

136,351 |

0percent |

136,899 |

0percent |

161,398 |

18percent |

151,682 |

-6percent |

| Enforcement |

396,824 |

444,784 |

12percent |

1,164,312 |

162percent |

581,792 |

-50percent |

412,013 |

-29percent |

422,539 |

3percent |

| Higher Courts |

109,037 |

120,817 |

11percent |

125,132 |

4percent |

173,319 |

39percent |

259,716 |

50percent |

254,759 |

-2percent |

| Civil Litigious Cases |

49,287 |

54,134 |

10percent |

62,239 |

15percent |

110,566 |

78percent |

160,243 |

45percent |

113,547 |

-29percent |

| Civil Non-Litigious Cases |

4,315 |

9,074 |

110percent |

9,630 |

6percent |

7,395 |

-23percent |

9,998 |

35percent |

16,694 |

67percent |

| Criminal Investigation |

3,103 |

3,705 |

19percent |

2,851 |

-23percent |

2,708 |

-5percent |

2,833 |

5percent |

2,903 |

2percent |

| Criminal (Other than Investigation) |

52,332 |

53,904 |

3percent |

50,412 |

-6percent |

52,650 |

4percent |

86,642 |

65percent |

121,615 |

40percent |

| Appellate Courts |

66,817 |

60,032 |

-10percent |

61,191 |

2percent |

59,474 |

-3percent |

65,757 |

11percent |

63,187 |

-4percent |

| Misdemeanor Courts |

551,039 |

669,559 |

22percent |

786,261 |

17percent |

696,607 |

-11percent |

676,361 |

-3percent |

614,246 |

-9percent |

| Appellate Misdemeanor Court |

37,563 |

30,597 |

-19percent |

26,604 |

-13percent |

26,520 |

0percent |

28,856 |

9percent |

28,786 |

0percent |

| Administrative Court |

20,149 |

18,681 |

-7percent |

19,274 |

3percent |

19,180 |

0percent |

18,666 |

-3percent |

21,285 |

14percent |

| Commercial Courts |

83,021 |

92,151 |

11percent |

95,152 |

3percent |

104,080 |

9percent |

127,720 |

23percent |

140,082 |

10percent |

| Appellate Commercial Court |

11,347 |

11,315 |

0percent |

12,805 |

13percent |

12,470 |

-3percent |

15,446 |

24percent |

16,993 |

10percent |

| Supreme Court of Cassation |

7,396 |

19,109 |

158percent |

12,457 |

-35percent |

17,682 |

42percent |

13,129 |

-26percent |

19,038 |

45percent |

| TOTAL |

1,793,212 |

2,087,332 |

16percent |

2,953,921 |

42percent |

2,335,760 |

-21percent |

2,298,870 |

-2percent |

2,268,769 |

-1percent |

Source: SCC Data

Figure 28: Total Dispositions by Court Type from 2014 to 2019

Source: SCC Data

- The sudden peak in dispositions of Basic Courts in 2016

was caused by an almost three-fold increase in resolved enforcement

cases. This extraordinary result arose from the passage of the

Law on Enforcement and Security , which produced a

dramatic number of dismissals of enforcement cases, as discussed above,

particularly in 2016 (see Box 5). If enforcement cases are not

considered, Basic Courts disposed of only five percent more cases in

2016 than in 2015.

- Probate cases entrusted to public notaries inflated the

disposition numbers for Basic Courts. The SCC mentioned in its

2019 Annual Report that Basic Courts delegated 122,708

of the 134,226 probate cases they had received to public notaries, and

the only work done by the courts was processing the delegations. The

delegations represented around 40 percent of the Basic Courts’ 290,623

civil non-litigious cases in 2019. For more on the activities of

notaries, see the discussion in section 1.3.4 Public Notaries: A

Promising Start below.

- The limited issues involved in many cases handled by

Higher, Commercial, and Misdemeanor Courts contributed to the higher

number of dispositions in these courts. Repetitive issues were

notable in military reservist cases in Higher Courts, commercial

offenses in Commercial Courts, and commercial, traffic, and misdemeanor

warrant execution cases in Misdemeanor Courts.

- Available data does not explain the decreasing number of

dispositions in the Administrative Court through 2018. The

Court’s caseload increased through 2018, but its dispositions declined,

even though its number of judges remained fairly stable through those

years. In 2019 the Court had seven fewer

judges than it had in 2018, and the incoming caseload declined by 11

percent while dispositions grew by 14 percent. However, even this

increase in dispositions was not enough to stop the accumulation of more

pending cases.

Box 10: Innovative Ideas for Better Caseload Distribution

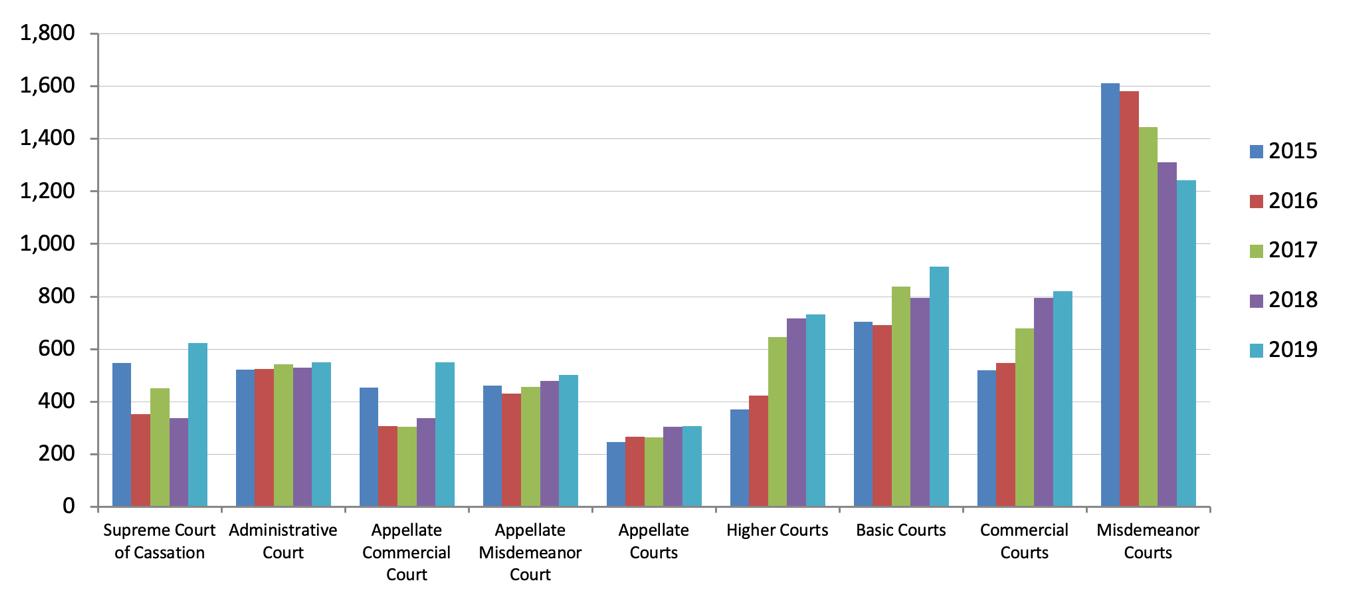

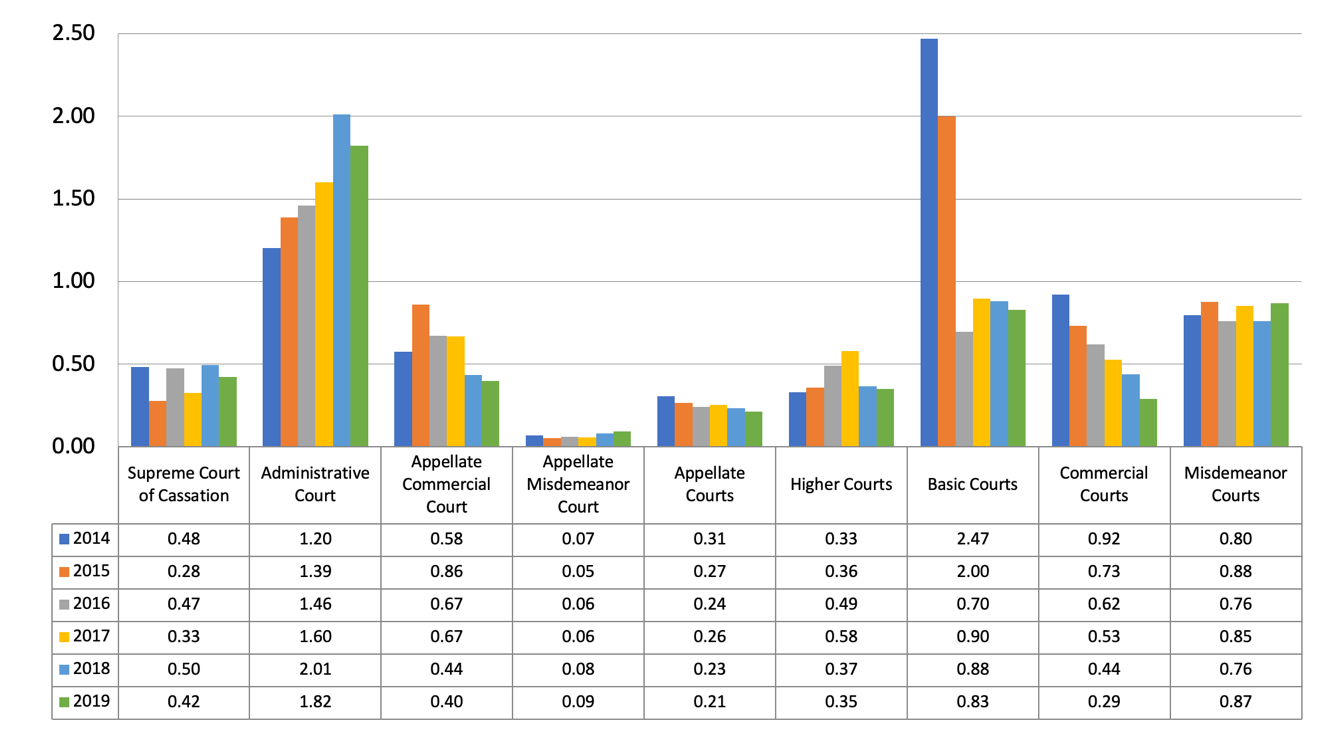

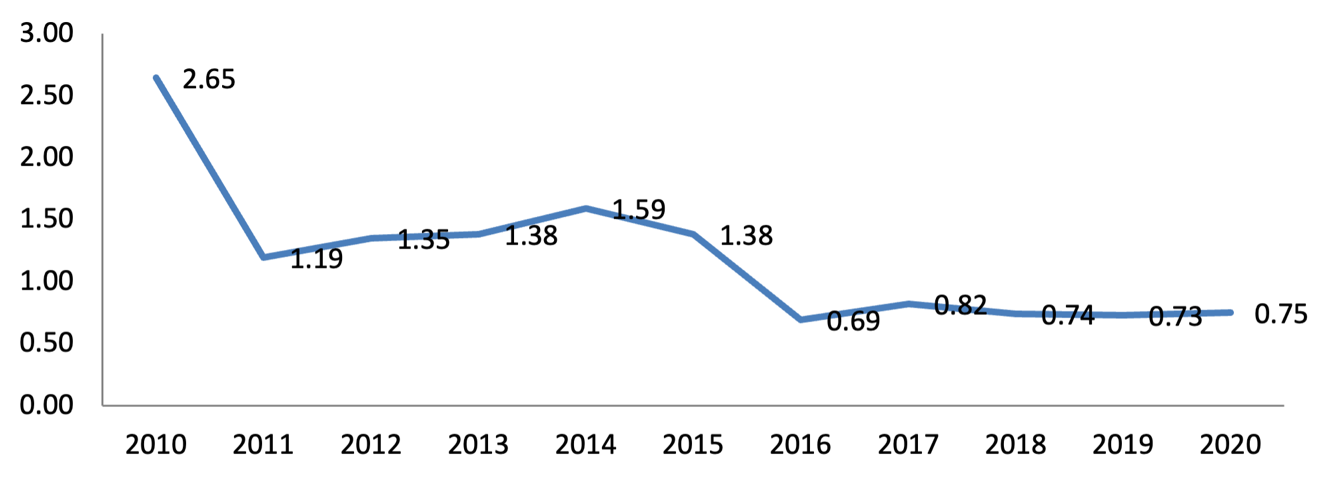

Dispositions per Judge

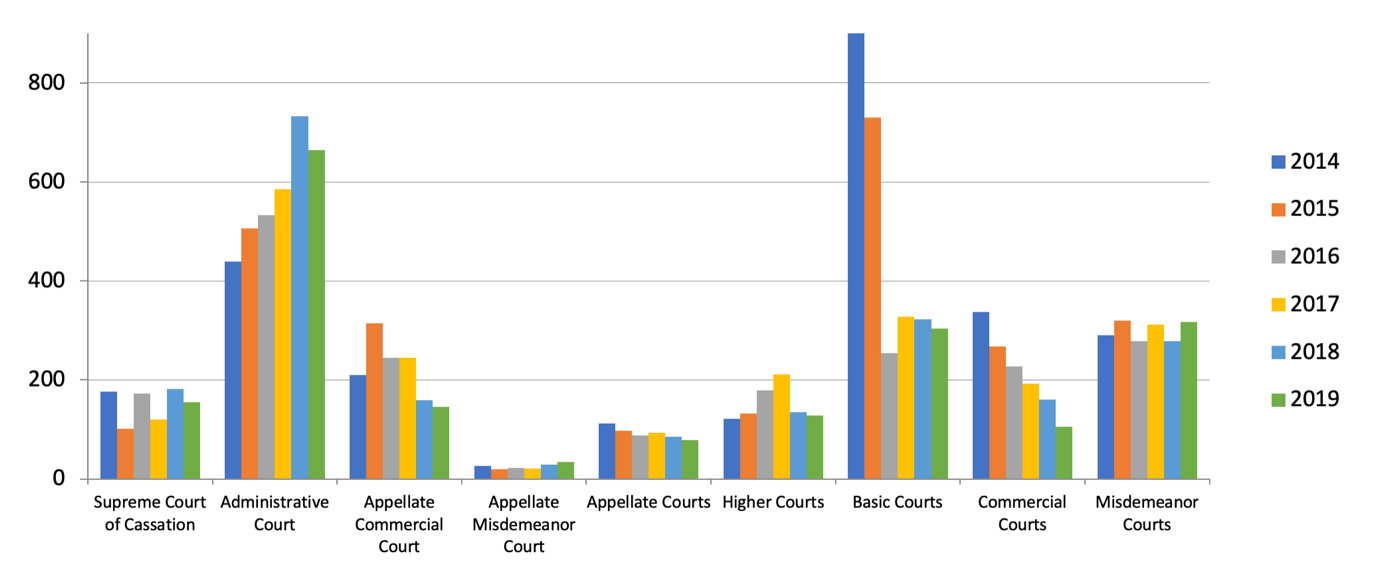

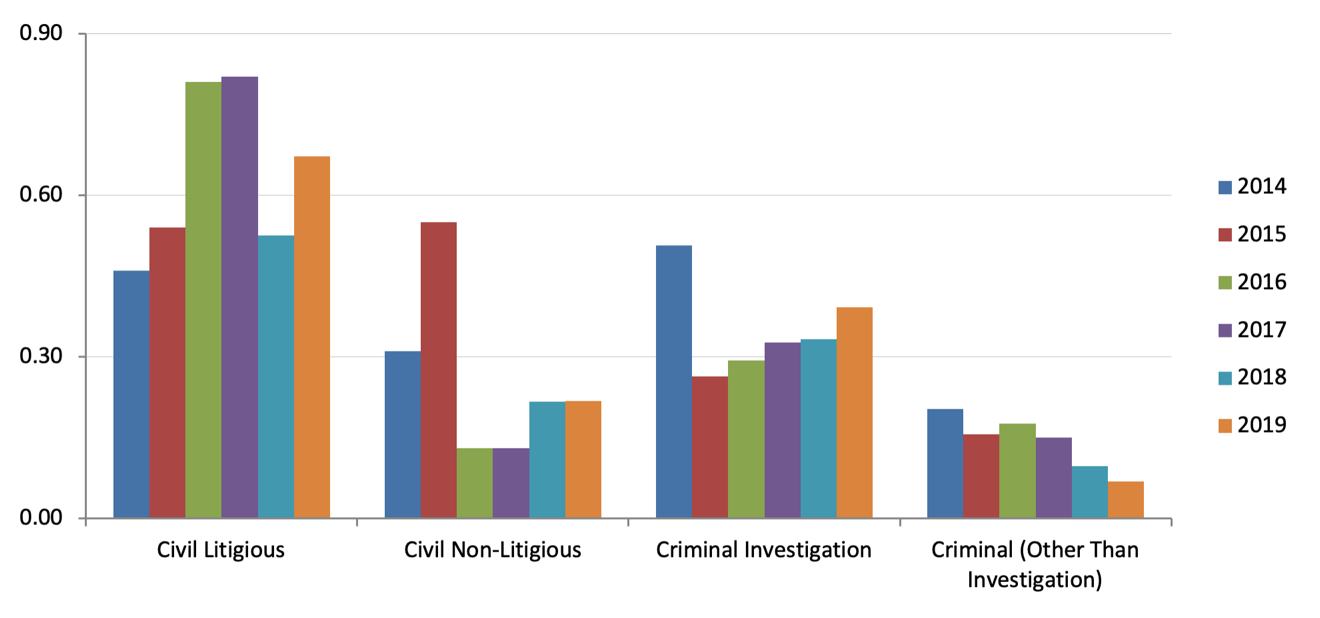

- Dispositions per judge, measured by dividing the number

of disposed of cases by the number of judges, displayed substantial

variations over time. In absolute numbers, Basic and

Misdemeanor Courts had the most significant differences in dispositions

among their judges, while the most stable dispositions per judge were

recorded in the Appellate Misdemeanor Court. Dispositions per judge

continuously increased in the Higher Courts and the Commercial Courts.

In the SCC, dispositions per judge varied from year to year, while in

the Administrative Court they declined sharply in 2018 only to recover

again in 2019. Figure 29 below gives an overview.

Figure 29: Average Dispositions per Judge from 2015 to 2019

Source: SCC Data and WB Calculations

- Dispositions per judge in Basic Courts peaked in 2016 to

1,322, due to the high number of dismissed enforcement cases.

In other observed years, the average number of dispositions varied

within less dramatic values. Without enforcement cases, the averages of

Basic Court reported dispositions per judge would have been far lower

but still increased consistently (452 in 2015, 474 in 2016, 509 in 2017,

565 in 2018, and 589 in 2019).

- As with the averages for caseload per judge, there was no

correlation between court size and the disposition per judge ratio, as

displayed in Table 6 below. Of 66 analyzed courts, 23 percent

were within the average values, 38 percent were above average, and 39

percent were below average. Belgrade’s Basic Courts fell into the

above-average category, together with other courts of various

sizes.

Table 6: Average Dispositions per Judge in Basic Courts in 2019

| Lebane |

7,437 |

5 |

1,487 |

Pirot |

10,514 |

12 |

876 |

| Aleksinac |

12,669 |

9 |

1,408 |

Despotovac |

6,796 |

8 |

850 |

| Third Belgrade |

53,229 |

38 |

1,401 |

Prokuplje |

15,221 |

18 |

846 |

| First Belgrade |

148,671 |

115 |

1,293 |

Brus |

4,093 |

5 |

819 |

| Knjazevac |

6,437 |

5 |

1,287 |

Jagodina |

14,661 |

18 |

815 |

| Mladenovac |

18,021 |

14 |

1,287 |

Krusevac |

20,298 |

25 |

812 |

| Kragujevac |

54,945 |

43 |

1,278 |

Novi Pazar |

12,155 |

15 |

810 |

| Sombor |

22,603 |

18 |

1,256 |

Raska |

3,889 |

5 |

778 |

| Pozega |

9,900 |

8 |

1,238 |

Petrovac on Mlava |

5,289 |

7 |

756 |

| Uzice |

20,958 |

17 |

1,233 |

Ub |

4,502 |

6 |

750 |

| Leskovac |

40,376 |

33 |

1,224 |

Surdulica |

9,513 |

13 |

732 |

| Bor |

14,197 |

12 |

1,183 |

Obrenovac |

5,808 |

8 |

726 |

| Kraljevo |

15,202 |

13 |

1,169 |

Senta |

5,744 |

8 |

718 |

| Subotica |

23,155 |

20 |

1,158 |

Lazarevac |

7,163 |

10 |

716 |

| Nis |

70,202 |

64 |

1,097 |

Backa Palanka |

6,430 |

9 |

714 |

| Second Belgrade |

48,413 |

45 |

1,076 |

Gornji Milanovac |

4,281 |

6 |

714 |

| Sremska Mitrovica |

9,647 |

9 |

1,072 |

Mionica |

3,527 |

5 |

705 |

| Vrbas |

16,069 |

15 |

1,071 |

Vrsac |

8,940 |

13 |

688 |

| Velika Plana |

12,796 |

12 |

1,066 |

Paracin |

14,248 |

21 |

678 |

| Zrenjanin |

22,382 |

21 |

1,066 |

Ruma |

8,080 |

12 |

673 |

| Loznica |

14,621 |

14 |

1,044 |

Zajecar |

12,689 |

19 |

668 |

| Veliko Gradiste |

4,163 |

4 |

1,041 |

Ivanjica |

6,406 |

10 |

641 |

| Prijepolje |

7,249 |

7 |

1,036 |

Pancevo |

15,953 |

25 |

638 |

| Kikinda |

11,370 |

11 |

1,034 |

Stara Pazova |

12,512 |

20 |

626 |

| Kursumlija |

4,933 |

5 |

987 |

Bujanovac |

6,017 |

10 |

602 |

| Becej |

6,802 |

7 |

972 |

Novi Sad |

51,869 |

92 |

564 |

| Trstenik |

5,811 |

6 |

969 |

Sjenica |

2,757 |

5 |

551 |

| Vranje |

24,643 |

26 |

948 |

Negotin |

6,525 |

12 |

544 |

| Cacak |

19,563 |

21 |

932 |

Sid |

2,858 |

6 |

476 |

| Arandjelovac |

10,920 |

12 |

910 |

Priboj |

2,369 |

5 |

474 |

| Pozarevac |

22,736 |

25 |

909 |

Valjevo |

11,832 |

27 |

438 |

| Sabac |

26,146 |

29 |

902 |

Majdanpek |

1,682 |

5 |

336 |

| Smederevo |

17,922 |

20 |

896 |

Dimitrovgrad |

1,584 |

5 |

317 |

Source: SCC Data and WB Calculation

- Misdemeanor Courts produced an average of 1,207 disposed

cases per judge in 2019, which was a decrease of 22 percent from 2016

although there were many variations among courts. This 22

percent drop occurred even though these courts overall had the same

numbers of judges in 2019 as they did in 2016, after two years of

considerably fewer judges. Dispositions per judge in

Misdemeanor Courts peaked temporarily in 2016 as judges worked to

resolve an increased inflow of traffic, commercial, and misdemeanor

warrant execution cases. In contrast, average dispositions for the

Appellate Misdemeanor Court were relatively stable overall: 478 cases

resolved per judge In 2015, 429 in 2016, 457 in 2017, 465 in 2018, and

496 in 2019.

- The Higher Courts’ disposition per judge increased

steadily in 2015 and 2016, with jumps of roughly 40 percent in 2017 and

2018. These judges each disposed of 350 cases on average in

2015, 370 in 2016, 528 in 2017, 730 cases in 2018, and 749 in 2019, even

though the total number of judges varied by only five percent over the

same period. The 2017 disposition per judge increased primarily due to

cases filed by military reservists that flooded the Higher Courts. In

2018 and 2019, this ratio was heavily influenced by ‘KR’ cases (see para

30).

- Disposition per judge in Commercial Courts grew

consistently, with notable increases in 2017, 2018, and 2019 despite

fluctuating numbers of judges. From 2015 to 2017, Commercial

Courts lost 13 judges and then gained 15 in 2018, only to lose 10 in

2019. The average number of disposed of cases for Commercial Court

judges was 576 cases in 2015, 602 cases in 2016, 708 in 2017, 788 in

2018, and 922 in 2019. The increases were triggered by a rising incoming

caseload of commercial offenses, which involved relatively limited

issues. Concurrently, the Appellate Commercial Court had 32 judges in

2015, 41 judges in 2018, and 31 in 2019. Their average disposition per

judge ranged from a minimum of 312 in 2017 to a maximum of 548 cases in

2019.

- Appellate Courts exhibited lower dispositions per judge

than the SCC from 2015 to 2019 since the SCC had higher incoming

caseloads. Similar situations can be seen in comparator

jurisdictions (e.g. in Montenegro). Nevertheless, this calls for greater

attention, possibly, the SCC’s jurisdiction needs to be revised because

too many cases reach it or the caseload is inflated by simple matters.

The numbers per judge for the SCC were 503 in 2015, 337 in 2016, 453 in

2017, 320 in 2018 and 577 in 2019. For Appellate Courts, the average

dispositions per judge were 267 in 2015, 272 in 2016, 261 in 2017, 304

in 2018, and 318 in 2019.

Court Rewards Program

- The SCC’s competitive Court Rewards Program, which put

Serbia at the forefront of innovation among European judiciaries in

incentivizing court performance, deserves to be expanded to recognize

the benefits of more initiatives by lower courts. The Rewards

Program was included in the Supreme Court of Cassation’s Court Book of

Rules to motivate courts and the people working in them to improve court

operations. Launched by the SCC in 2016, the Rewards Program had gone

through four cycles by the end of 2019. There was no competition in 2020

presumably because of the difficulties all courts had in executing even

routine operations in the face of Covid-19 concerns and

restrictions.

- Monetary prizes were set at a level the SCC hoped would

attract entries and which could be used for the benefit of winning

courts as a whole. The awards also bestowed recognition and

prestige on all entrants. Winning courts could choose to spend their

prize money on ICT hardware, office equipment, or materials for the

beautification of the court.

- The Program appropriately focused on solving some of the

most troublesome issues facing the Misdemeanor, Basic, Higher and

Commercial Courts by making awards for the “most

considerable improvement in backlog reduction” and the “largest

improvement in the number of resolved cases per judge.” Winners

have been drawn from each group of courts, as shown in Table 7 below. By

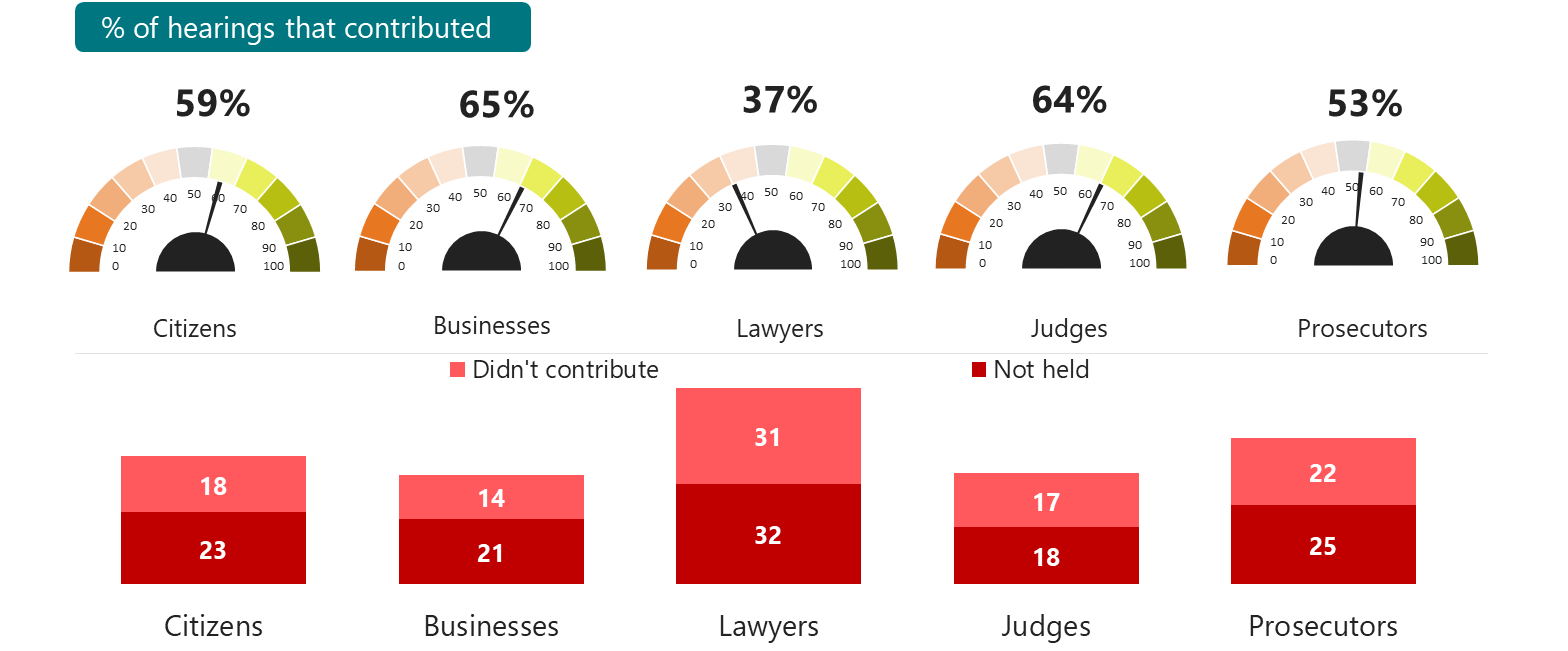

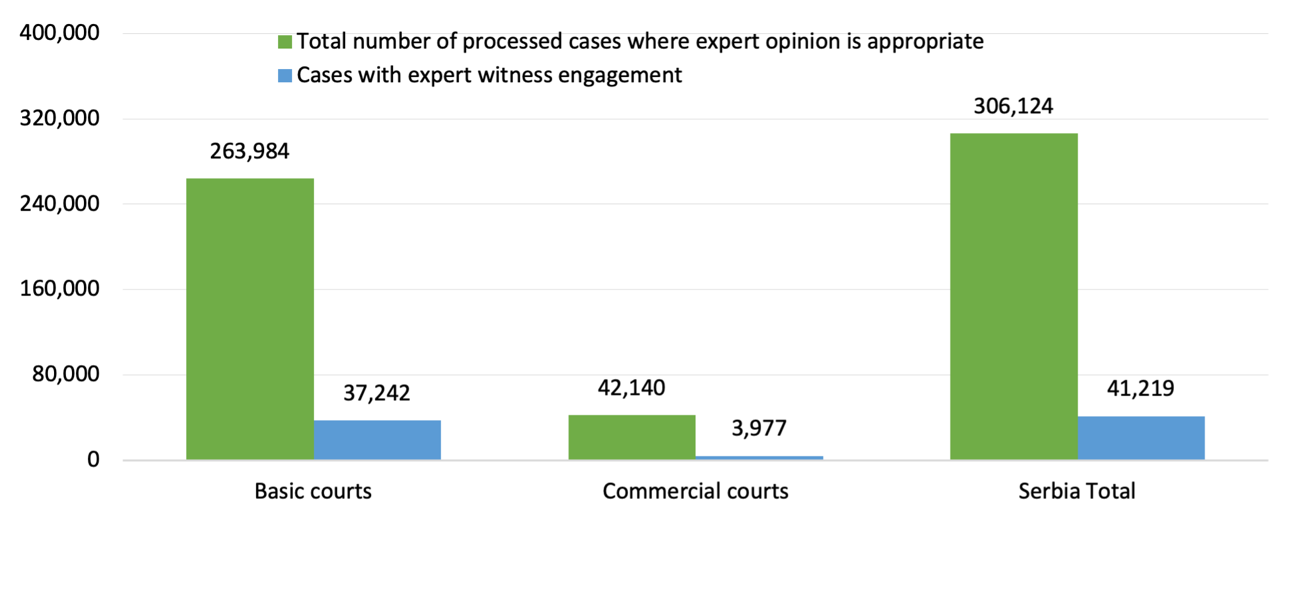

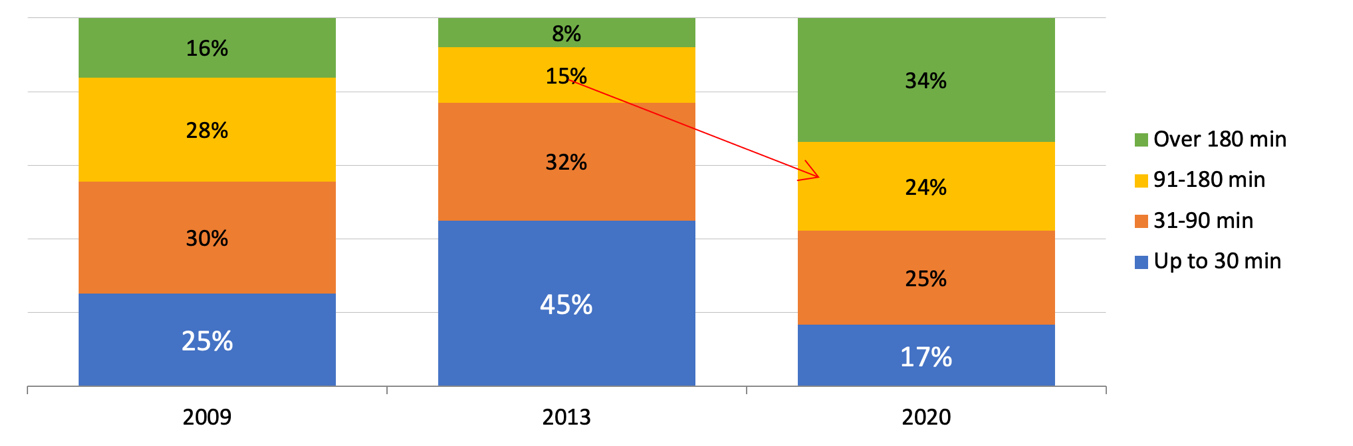

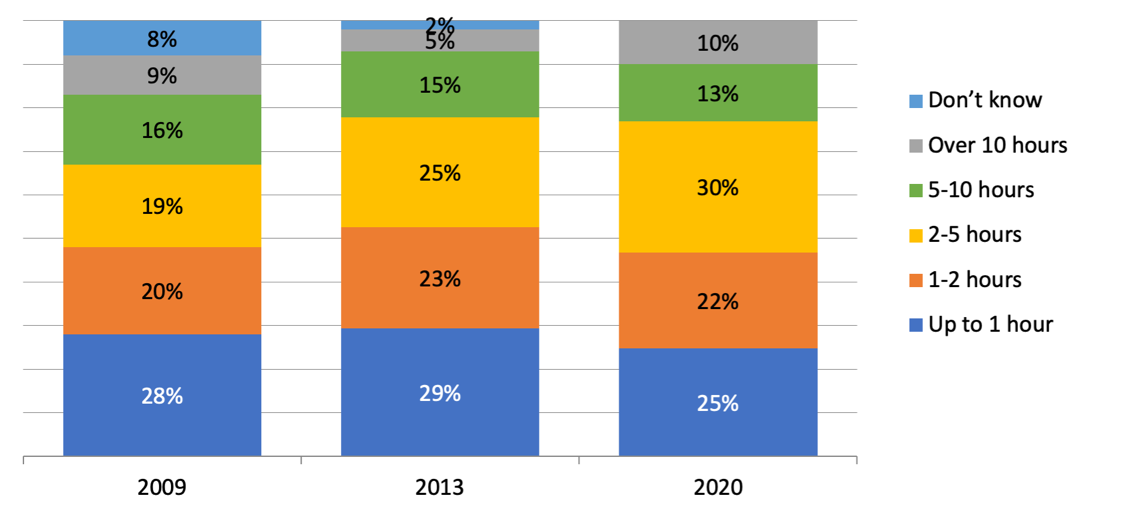

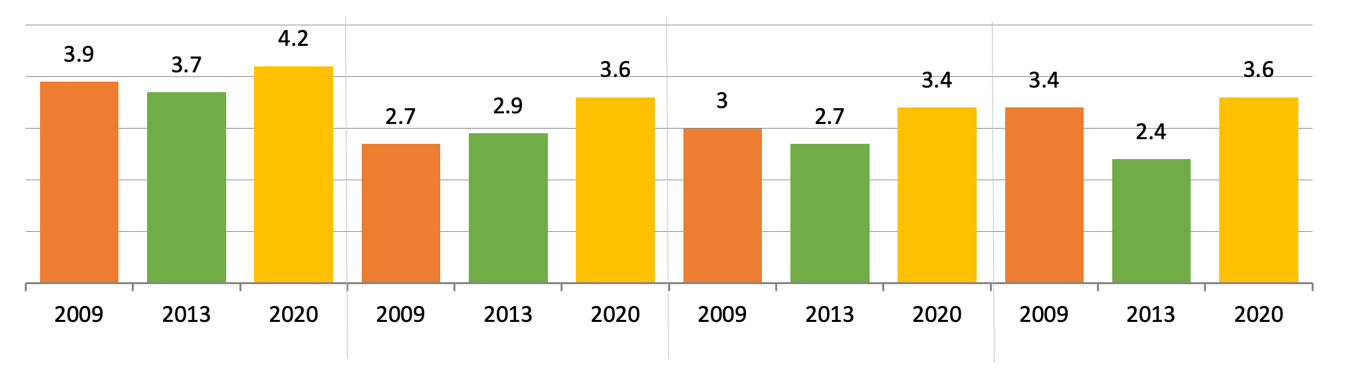

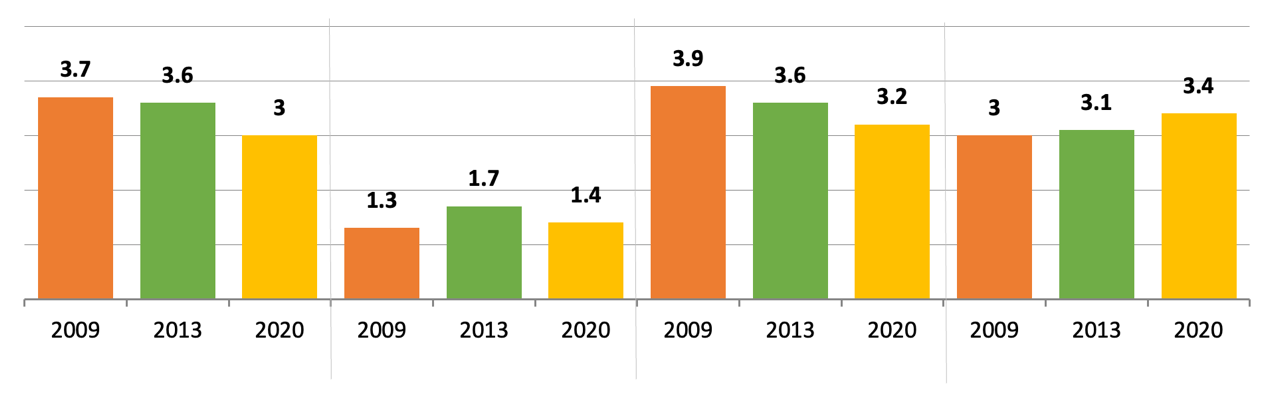

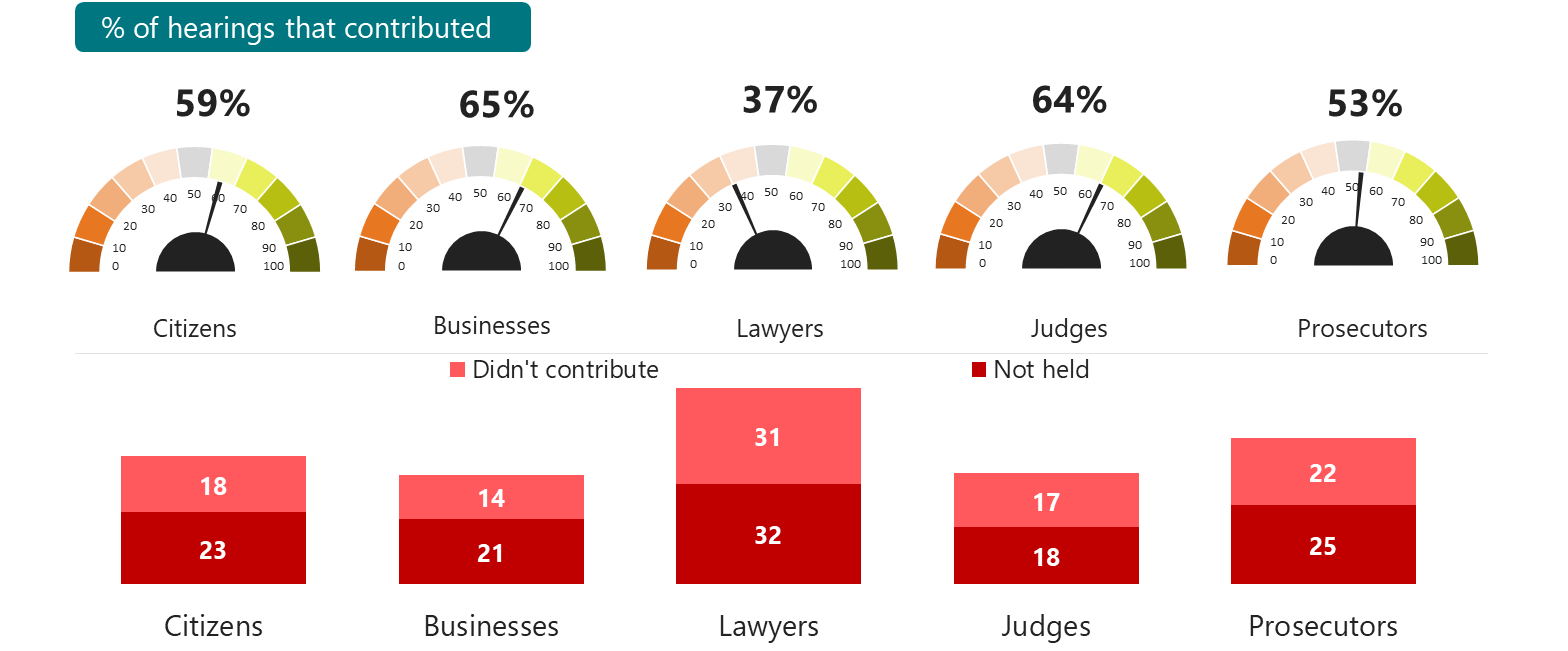

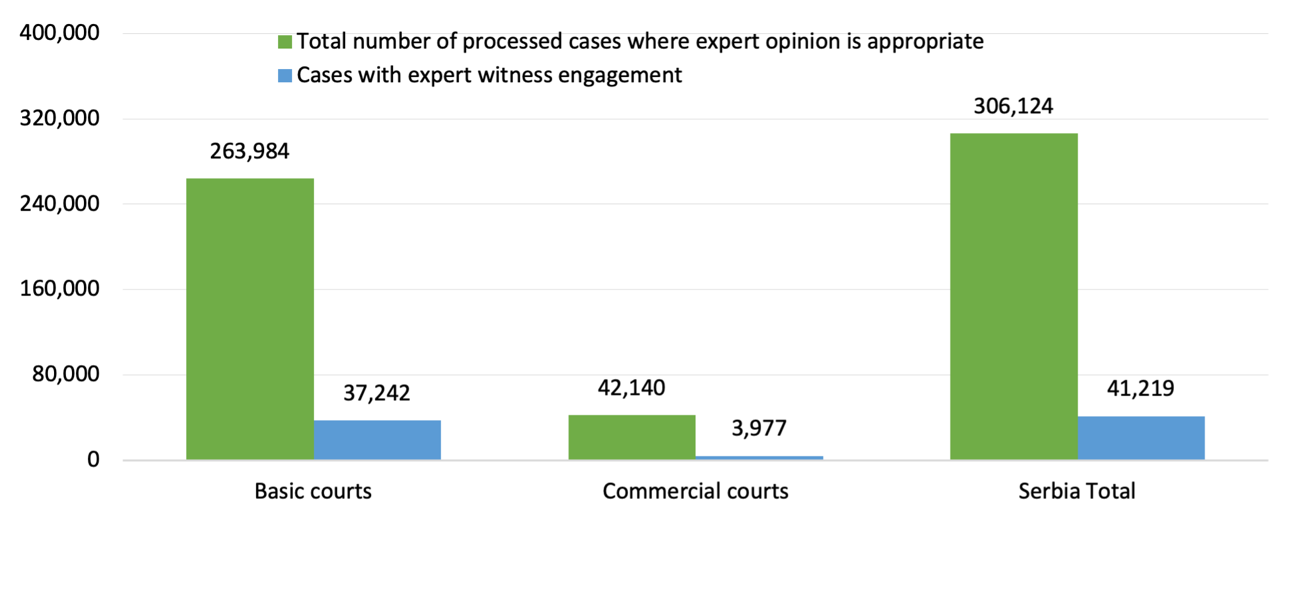

focusing on ‘most improved player’ awards, the program has aimed to