Access to Justice Services

Main findings ↩︎

- While Serbia lags behind other European countries in

access to justice, it has improved since 2013. Key improvements

include the Law on Free Legal Aid, the Central Application for Court

Fees (to facilitate application for fee waivers),

online databases of law and case status, and incentives for mediation.

There remains room to improve affordability, information, management,

and evaluation of access to legal services.

- Affordability remained the most serious barrier to access

to justice in Serbia for citizens and businesses. Court and

attorney costs represent a significant proportion of average income in

Serbia, even for a simple case. Businesses report that the courts are

becoming increasingly inaccessible due to court and attorney costs.

Small businesses are the most affected.

- The application of court fee waivers is still not

unified, resulting in inconsistent access to justice services for the

indigent. Rules on court fee waivers are not comprehensive,

lacking deadlines for submitting a request for exemption and deadlines

for the court to decide on the request. There is very limited

understanding among members of the public of the court fee waiver

program. There are no guidelines or

standardized forms for judges who grant a waiver, and decisions go

largely unmonitored. Except for the amount of court fees, the parties

often point to unequal treatment by the courts and the lack of

information as the key problems experienced in waiving fees. Waivers may improve access to

justice in some areas, but without data their impact cannot be

monitored.

- Attorney fees are more highly prescribed than in many EU

member states. Attorneys are paid per hearing or motion. This

encourages protracted litigation and reduces the ability of low-income

citizens to pay for legal services.

- Ex officio attorneys may be appointed for indigent

clients, but there are concerns regarding their quality control and

impartiality. To enable equal distribution of cases among ex

officio attorneys, the Bar Association of Serbia introduced a call

center and software for tracking.

- In accordance with the Serbian Constitution and European

principles of justice, a legal aid system was established in October

2019. The Law on Free Legal Aid provides two distinct

categories – legal aid and legal support. Legal aid is provided by

lawyers and municipal legal aid services and by civil society

organizations in cases of asylum and discrimination.

- Municipal legal aid services receive citizens’ requests

for free legal aid and decide on their eligibility based on their

financial situation. Legal aid is provided for all case types

except commercial and misdemeanor cases where a prison sentence is not

envisaged. Persons eligible to receive legal aid are those who already

receive social benefits, children receiving child benefits and members

of certain vulnerable groups. In addition, individuals who do not

currently receive social or child benefits are eligible if payment of

legal aid from their own resources would render them qualified for

social benefits.

- The Ministry of Justice has limited resources to monitor

the new legal aid programs. The Ministry maintains a registry of legal

aid providers and decides on appeals against the denial of municipal

legal aid services. Only one employee is responsible for

implementing the new programs. Not all providers are submitting data to

the Ministry, and satisfaction with services is not tracked or assessed

at a central level.

- Effective implementation of the Free Legal Aid Law is

hindered by lack of proper budget planning and a shortage of funds in

municipalities’ annual budgets. In addition, some municipalities do not

keep a registry of free legal aid, which impacts the monitoring of

implementation. Furthermore, the Ministry of Justice has

recognized the challenge of unifying the practice of municipal legal aid

services to ensure equal access to justice for all citizens.

- More outreach is necessary to inform citizens about legal

aid and legal support. Most citizens are unaware of any free legal

services that might be provided in their municipality. To

improve cost-effectiveness, the participation of CSOs, legal aid centers

and law faculties should be encouraged.

- Awareness of law and practice has improved significantly

in the last five years, especially among professionals. Judges,

prosecutors, and lawyers can access the Official Gazette online database

of laws, bylaws and caselaw. The special website on court practice was

established in 2020, including a selected number of court decisions of

the Supreme Court of Cassation, appellate courts, the Administrative

Court, the Commercial Appellate Court and the Misdemeanour Appellate

Court, which significantly increases access to these among

professionals. These improvements in the accessibility of legislation

and jurisprudence contribute to the increasing quality and consistency

of court practice.

- The system for access to information by court users about

the courts in general and their own cases has improved. Portal

Pravosudje now enables access to information on the status of ongoing

procedures in all courts (all types and all instances), including

information on the status of cases handled by private bailiffs. In

addition, the development of e-court improved contact with the court and

enabled electronic communication. On the one hand, compared with 2009

and 2014, a lower percentage of citizens and business representatives

report that specific court and case information is accessible. On the

other hand, users directly involved in court cases reported a high level

of satisfaction in this respect, suggesting that those with immediate

experience have benefited from an updated system.

- Application of mediation is still limited, as well as

awareness of it by citizens and businesses. Additional outreach

initiatives to potential court users will be required, along with

intensive training for judges, prosecutors, lawyers, and court

staff. Further incentives should be built into the

institutional framework to encourage its use and integrate it into the

court system, such as the development of a special registry for

mediation cases which will allow the inclusion of these cases in the

results of judges’ evaluation and promotion.

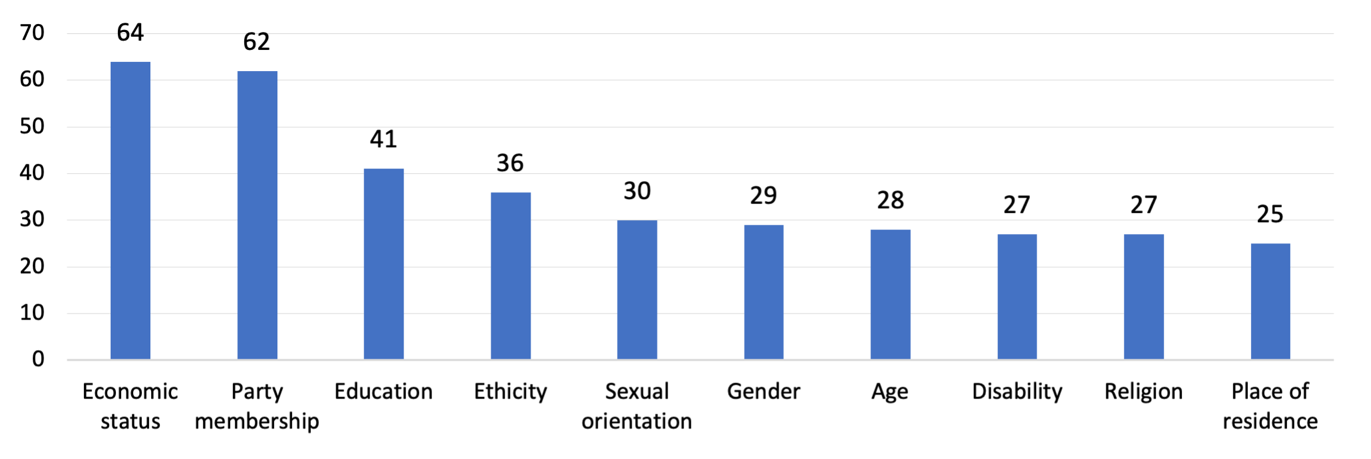

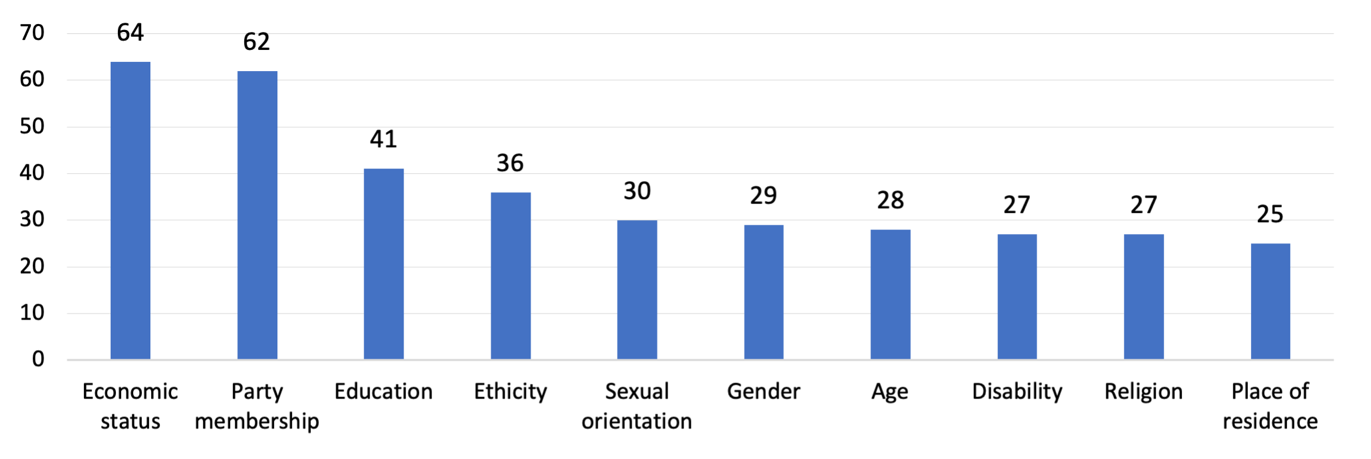

- Equality of access for vulnerable groups continues to

pose challenges. The majority of citizens surveyed reported that the

judiciary is not equally accessible to all citizens. Perceived

unequal treatment of citizens is primarily based on economic status and

party membership. Equal access to justice is also seen to be denied to

citizens who have less education and also based on ethnicity, sexual

orientation and gender.

Introduction ↩︎

- Access to justice is a basic principle of the rule of law

and includes several dimensions: individuals’ access to courts, legal

representation for those who cannot afford it, and equality of

outcomes. There is no access to justice where citizens,

especially marginalized groups, fear the system and so do not use it,

where the justice system is financially inaccessible, where individuals

lack legal representation, or where they do not have information or

knowledge of their rights. The EC emphasizes the importance of enhanced

access in justice system reform and relevant parts are included in the

Action plan for Chapter 23.

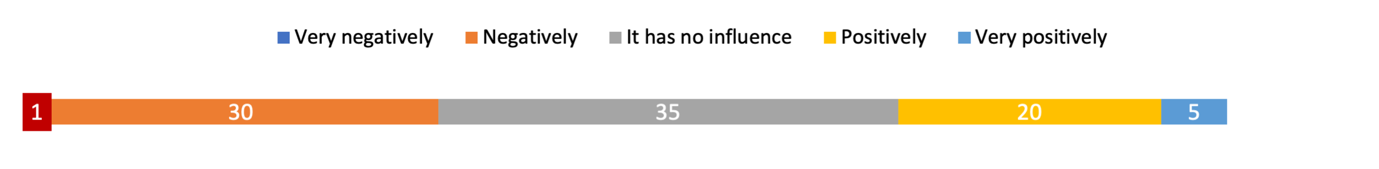

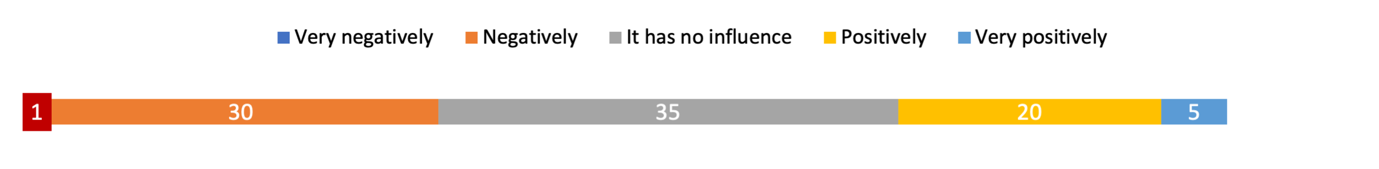

- Access to justice is also an economic development

concern, as constraints on access to justice appear to create a drag on

businesses. As in 2013, the judicial system remains an obstacle

for the business environment. Around one-third of business sector

representatives reported that the situation in the justice system

negatively impacts the business environment in Serbia.

However, another 35 percent of respondents reported that the justice

system has no influence or impact on the business environment and 25

percent believed it had a positive or very positive impact on the

business climate. (see Figure 100). However, the size of the company and

sector have an impact on the perception. Bigger companies perceive the

positive impact as greater, 49.3 percent of enterprises with more than

50 employees believe that the justice system has a positive impact on

the business environment, compared to 17 percent of enterprises with up

to 9 employees. Enterprises in the services and trade sectors (25

percent) perceive a positive impact more than those in the manufacturing

sector (11.6 percent).

Figure 100: In your opinion, how does the current situation in the

justice system affect the business environment in your country?

Source: Understanding Barriers to Doing Business:

Survey Results of How the Justice System Impacts the Business Climate in

South East Europe, World Bank, 2019

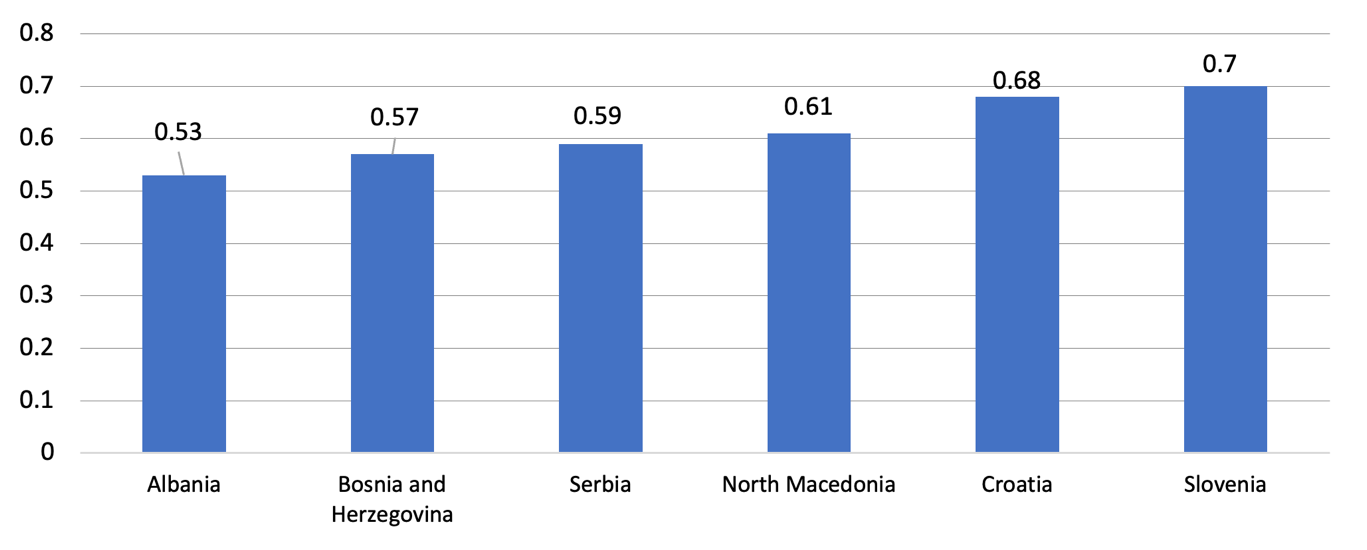

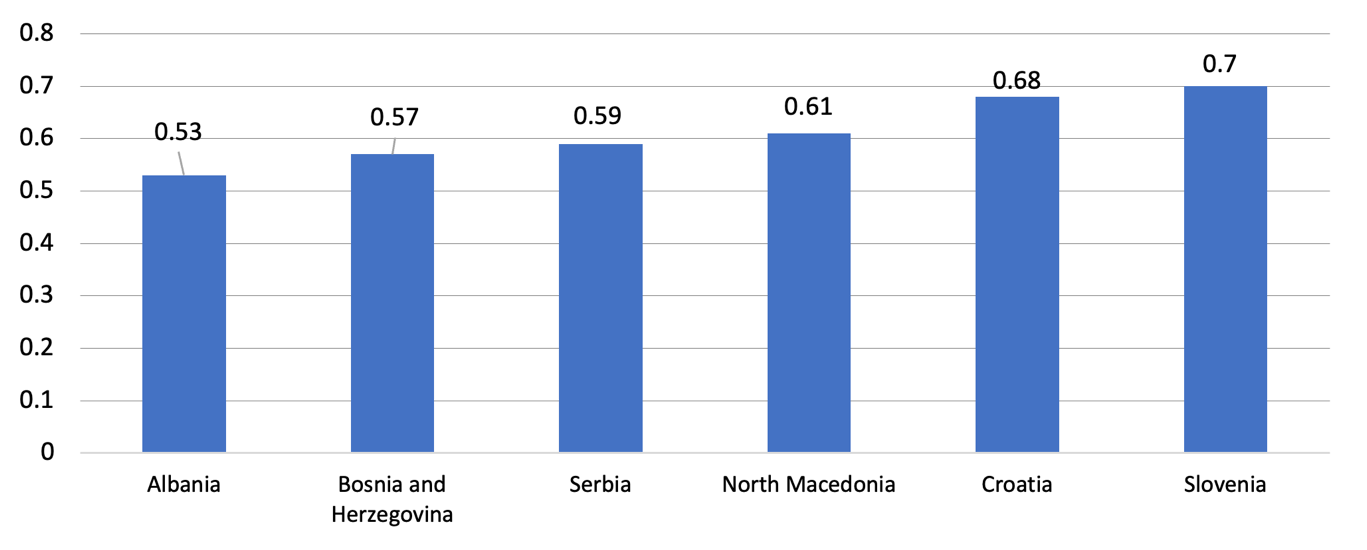

- In comparison with the rest of Europe, Serbia lags behind

in access to justice. According to the World Justice Project’s

Rule of Law Index 2020, Serbia ranks the low among the EU countries in

terms of accessibility and affordability of the civil justice system

(see graphs below). However, Serbia’s ranking improved from 2014 to 2020

from 0.48 to 0.59. Additionally, Serbia’s ranking

improved in comparison to non-EU neighboring countries and according to

2020 data, access to justice is better than in Albania and Bosnia and

Herzegovina.

Figure 101: Access and Affordability of Civil Justice, EU and Serbia,

WJP Rule of Law Index  2020

2020

Figure 102: Access and Affordability of Civil Justice, Regional

Countries and Serbia, WJP Rule of Law Index 2020

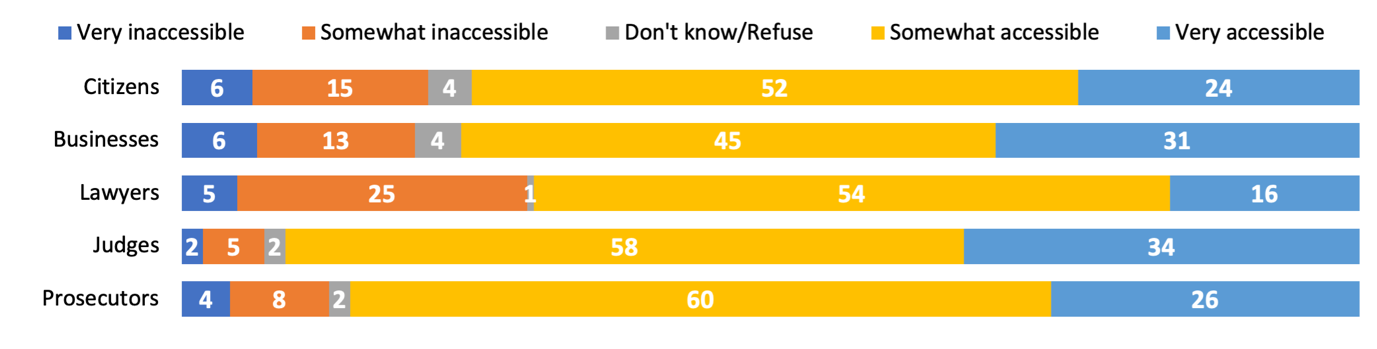

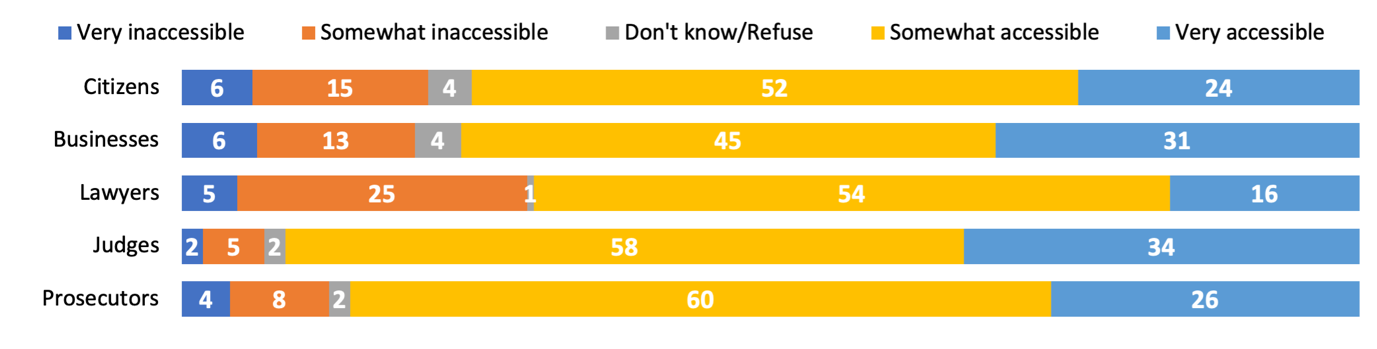

- According to the 2020 Regional Justice Survey, the

perception of courts accessibility is high, however, it differs among

individuals inside the system, those working with the system, and those

outside it. For example, the Survey found that judges and

prosecutors perceive the system as most accessible; in excess of 85

percent rated the system as accessible, and 76 percent of the general

public rated the system as accessible. Individuals within the system,

particularly judges and prosecutors, and those without frequent

interactions with the system may not be well placed to assess access to

justice. The negative perception of accessibility is the highest among

lawyers, among whom 30 percent rated the system as

inaccessible.

Figure 103: General Perception of Court Accessibility

Affordability

of Justice Services (Financial Access to Justice) ↩︎

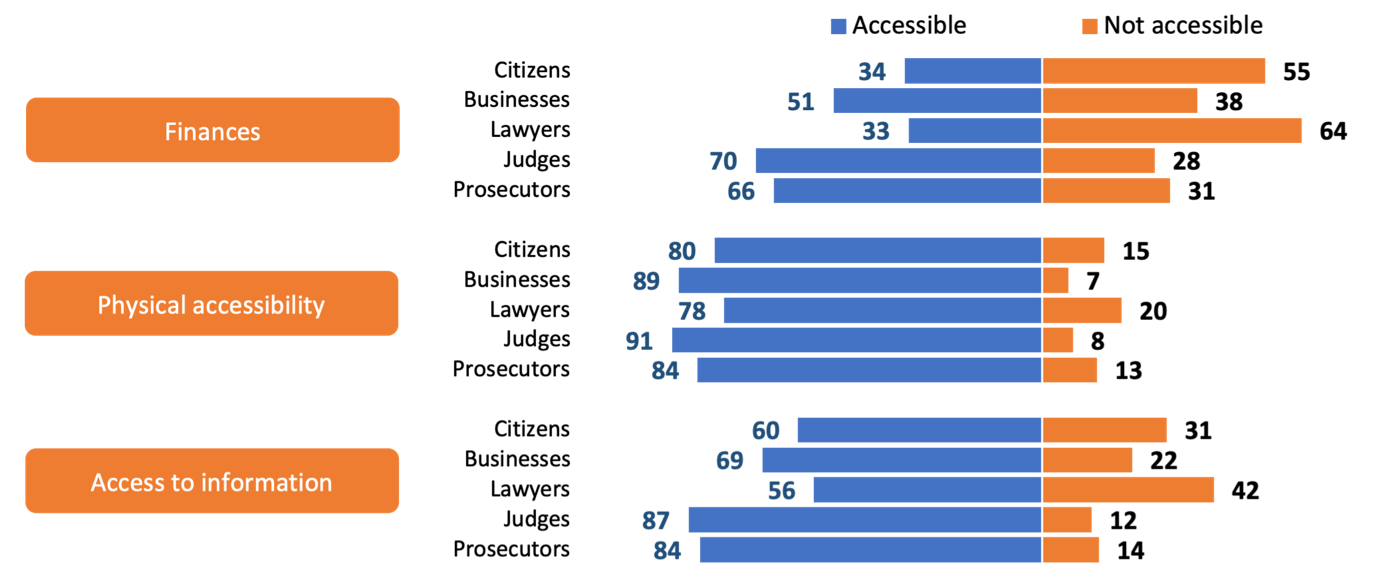

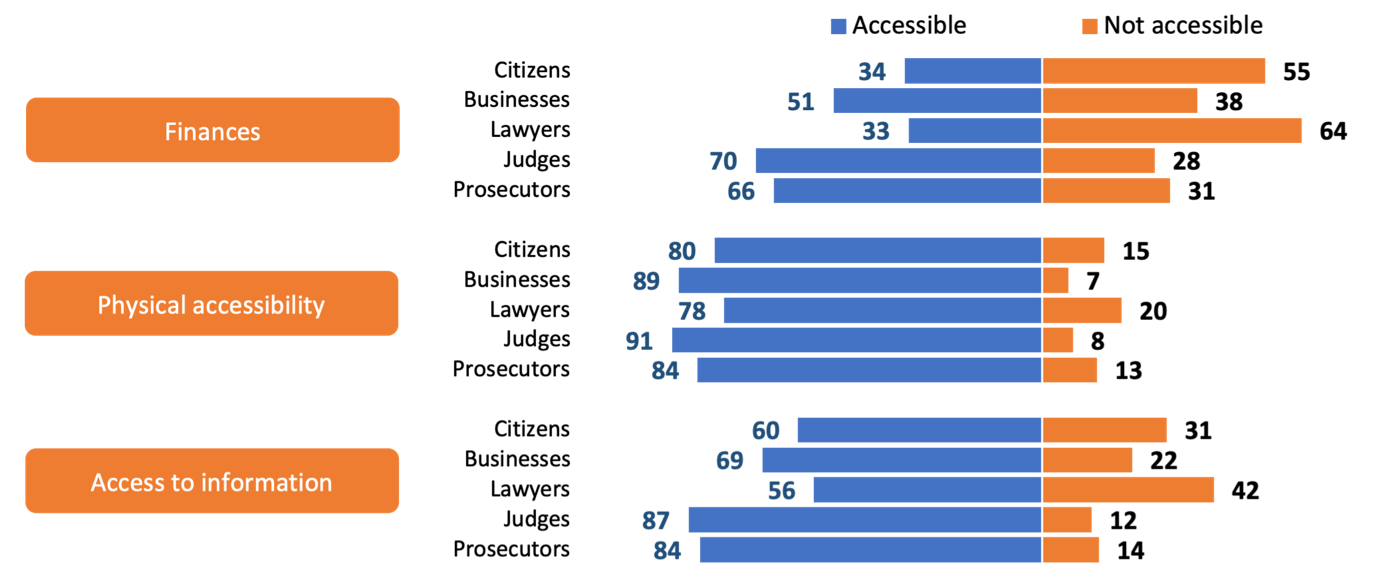

- Financial access to the court system remains the largest

barrier to access to justice for most Serbian citizens and business

representatives. More than half of citizens perceive

affordability as the biggest challenge to accessing the justice system,

while physical accessibility is recognized as a barrier only by 15

percent of citizens and 7 percent of the businesses.

Figure 104:General Perception of Three Specific Aspects of

Accessibility

- Costs of court cases increased from 2013 to 2020,

especially in civil cases, where costs are now three times

higher. On average, the cost of citizens’ first instance

proceedings was over 600EUR, which is higher than the average monthly

salary in Serbia. The increase of court costs

contributes to further court inaccessibility; already in 2013, when

costs were significantly lower, citizens perceived finances as deterrent

in 2013. Box 19 below gives an indication of average total costs for

court users in 2013 and 2020.

Box 19: How Much on Average Do Court Users Pay?

- Justice services entail many individual costs to the

user. The section below examines court-related costs,

lawyer-related costs, and specific financial access issues facing

lower-income Serbians, including court fee waivers, court-appointed

attorneys, and legal aid.

Affordability of Court Fees ↩︎

- The system of calculating court fees, as well as a method

of taxing and collecting them, set out in the Law on Court Fees, has not

been changed since 2013. Fees are based on

the stated value of the claim; in the litigation cases, it ranges from

1,900 RSD to 97,000 RSD, and in commercial cases, from 3,900 RSD to

390,000 RSD. Fees are paid on every motion

submitted, impacting how assertively claims

can be pursued, as well as on every decision rendered

and every court settlement reached in all litigious processes and

commercial disputes. In uncontested proceedings, a nominal fee of 390RSD

applies in some instances, though higher fees apply for uncontested

processes involving property, such as inheritance procedures or division

of property. In administrative proceedings, a nominal fee of 390RSD

applies for initiation of the process, as well as for every motion

submitted (e.g.., appeal, claim for repetition of proceedings).

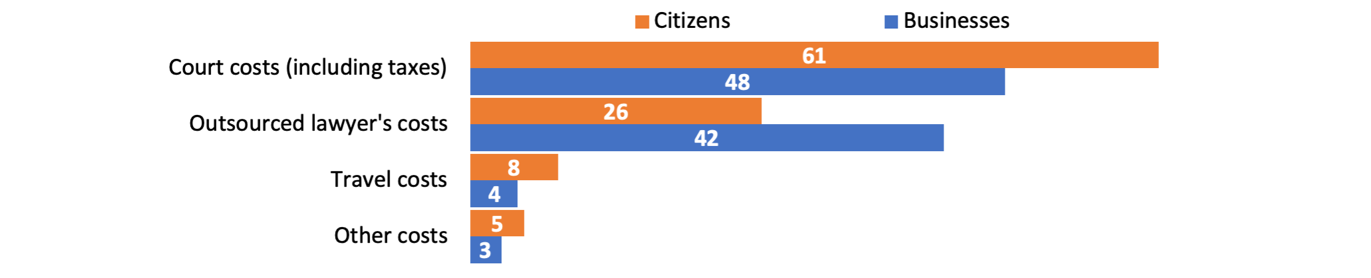

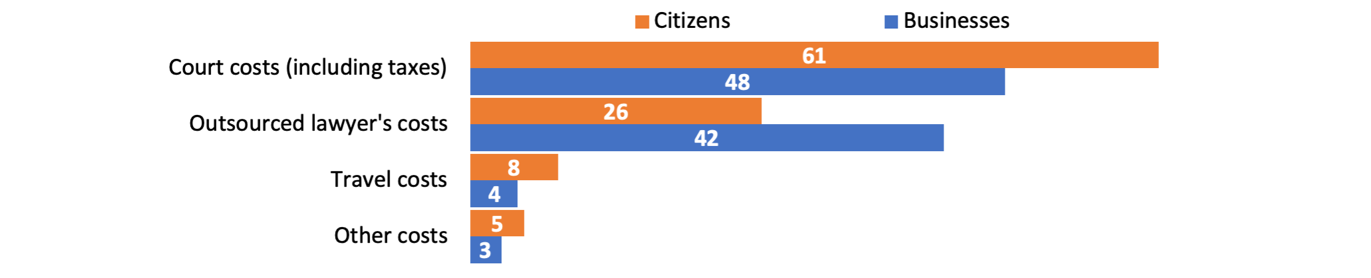

- Court users cite that court-related costs present more

than 60 percent of total case costs and present a considerable obstacle

to access to the judicial system in Serbia. In the 2020

Regional Justice Surveys, the public with experience in court

proceedings identified court costs as the most significant constraint as

well. Businesses also identified attorney costs as a significant

barrier.

Figure 105: Citizens and Businesses: Types of Costs of First Instance

Proceedings

- However, court fees represent a smaller portion of total

court case costs than attorneys’ fees, even when those are discounted

and vary widely by region. The financial burden of court cases

is especially high for users coming from less wealthy parts of the

country. As seen in Table 16 below, court and attorney fees for a

divorce case would require the average person in Novi Pazar to pay 80

percent of their monthly net income, even at the commonly discounted

attorney rate. The Novi Pazar resident would be required to pay nearly

150 percent of their monthly net income to cover the total costs of the

case if discounts were not applied. Court and attorney fees for a

divorce case in Belgrade, once discounted, would exceed 43percent

percent of the average Belgrade resident’s monthly net income.

Table 16: Divorce Costs as a Share of Average Income

| Novi Pazar |

45,475 |

5,320 |

62,250 |

67,570 |

11.6percent |

136.8percent |

148percent |

80.1percent |

| Belgrade First |

84,327 |

5,320 |

62,250 |

67,570 |

6.3percent |

73.8percent |

80.1percent |

43.2percent |

Source: Calculation of the World Bank

- The cap on court fees remained since 2014, so the

high-value civil cases continue to be relatively inexpensive compared

with lower-value cases. The stakeholders

reported that the cap distorts incentives when the cost of the claim is

high by encouraging very wealthy individuals or large companies to

pursue unmeritorious claims, exploit procedural inefficiencies or mount

frivolous appeals.

- The Law on Civil Procedure envisages that each party pays

court fees before they submit an initial claim or answer, but the court

will not suspend litigation for failure to pay fees. However,

many potential or unseasoned court users may not be aware of the

rule.

- The courts lack an online fee calculator that enables

potential litigants to estimate their court fees before filing a

case. The unified online fee calculator should be available on

all court websites, including explanations as to when a specific fee has

to be paid and whether it should be paid by a plaintiff, a defendant, or

both parties. Some courts have calculators that are not in compliance

with the last amendments of the Law on Court Fees, or some courts

present only the text of the Law. The fee-based user-friendly calculator

is available, but that should be provided by courts free of

charge.

Accessibility of Court Fee

Waivers ↩︎

- Fee waivers may be critical to achieving equality in

practice and enable access by lower-income individuals who are deterred

from court use because of costs.

The Law on Court Fees and the Civil Procedure Code allows court fee and

cost waivers for parties who are financially unable to cover

court-related costs. However, there is very limited understanding of the

court fee waiver option among the public; therefore, many potential

users who would be deterred from accessing the courts are unaware they

could use this benefit.

- Although the legislative framework provides various

possibilities for exemption from court fees, there are a number of

problems in practice. Both Law on Court Fees and Civil

Procedure Code do not include a deadline for submitting a request for

exemption of court fees nor a deadline for the court to decide on the

request. Also, the absence of regulation

often creates problems regarding the form of the decision, whether it

should be in the form of a special decision or it should be part of the

judgment.

- The lack of consolidated data on the implementation of

the court fee waiver rules further complicates the assessment of this

mechanism in practice.

- To overcome the problem of undocumented fees and

inconsistent application of the fee waiver program, the Central

Application for Court Fees (CSST) was developed in 2020. It has

yet to be seen if all functionalities of the application will be used

and if the judicial system will track all payments of the court fees,

including information about fee waivers.

- Though practice varies, stakeholders report that courts

primarily take into consideration the party’s property, income, and the

number of family members. Courts may also consider the party’s

financial dependents as well as the value of the claim.

In practice, interviewees indicated that judges would usually grant a

waiver if the party submits an official statement to show they are

unemployed and own no real estate. Recipients of social welfare may also

be free from the duty of pay related costs of the procedure, but again

this is applied inconsistently.

Affordability of Attorneys ↩︎

- Parties very often choose to hire a private attorney for

representation In civil and criminal cases even when not

required. The law requires only in some procedures that a party

be represented by an attorney, but in civil cases,

57 percent of court users reported hiring an attorney, while 65 percent

did so in criminal cases. However, in misdemeanor cases, only 10 percent

of citizens hired a private attorney.

- In most jurisdictions, lawyers are free to negotiate

their fees through agreement with their clients. Most countries have basic

principles regarding the fee structure and require that the fees are

adequate and proportionate depending on the value and complexity of the

case. In contrast, in Serbia, attorney fees and costs are highly

regulated, unlike in most EU Member States.

The Attorney Tariff on Costs and Fee Rates

specifies fees for each type of proceeding and each legal action or

motion. Parties can negotiate, but fees must not be greater than 500

percent nor less than 50 percent of the tariff rate.

- Attorneys are paid per hearing or motion, which is in

conflict with CCJE's opinion that ‘the remuneration of lawyers and court

officers should be fixed in such a way as not to encourage needless

procedural steps.’ Attorneys who accept

payment by the case are rare.

Mandatory Defense ↩︎

- Although the law requires the ex-officio appointment of

attorneys in some cases, no official

data are collected on the number of appointments or the types of cases

where the ex-officio appointment is most common.

- To overcome concerns regarding the integrity of the

process for identifying ex-officio attorneys, the Bar Association of

Serbia introduced a call center accompanied by software to track

information on mandatory defense.

The police, courts, or prosecutors can call and be directed to an

attorney while the call center officer uploads information on the ex

officio attorney to the software. This practice, introduced in February

2019, was perceived positively by stakeholders. The daily report on

called and engaged ex officio attorneys is published on the website of

the Bar Association. The software enables the production of the report,

but also as well as searches by the attorney or by the prosecutor

(police officer or judge) who requested the attorney, whether the

attorney refused to accept mandatory defense and their reasons for

rejection. The call center removed the burden from prosecutors who

previously reported challenges in ensuring attorneys were present during

the investigation.

- Stakeholders expressed concerns regarding undue influence

in the appointment of attorneys and the performance of ex officio

lawyers. The same concern has been expressed by the European

Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading

Treatment or Punishment (CPT) on several occasions. In 2018, it reported

that: “ex officio lawyers only met their clients in the court and

that in several cases they did not show any interest in having a

confidential conversation with their clients…Allegations were also made

about certain ex officio lawyers being more interested in maintaining

good relations with police officers than representing their

clients”.

- The work of ex-officio attorneys is not monitored to

ensure quality control. Information regarding appointments is

not entered into AVP, or if entered, it is as a ‘general remark’ not

suitable for running analytical reports. Some stakeholders report that

the quality of work by ex-officio attorneys is lower than party-funded

attorneys due to their limited accountability. Several stakeholders

allege that ex-officio attorneys are more likely to pursue unmeritorious

claims and appeals to increase their billings. In the absence of data or

quality control mechanisms, the Review team is unable to substantiate

these claims.

Legal Aid Programs ↩︎

- The right to an attorney provided at state cost when a

party to a non-criminal dispute cannot afford an attorney is outlined in

the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights,

the ECHR , and the

United Nation’s Principles on Access to Legal Aid in Criminal Justice

Systems. In Serbia, the Constitution guarantees the right to

legal aid. In recognition of the principle, Serbia, after years of

preparation, adopted the Law on Free Legal Aid in 2018.

The application of the Law started on October 1, 2019.

- The Law on Free Legal Aid lays out two distinct types of

assistance: legal aid and legal support. Legal aid is provided

by lawyers and municipal legal aid services and by civil society

organizations in cases of asylum and discrimination. Municipal legal aid

services receive citizens’ requests for free legal aid and decide on

their eligibility based on their financial situation (see Box 20 below).

Legal support, which includes general legal advice, filling forms,

preparation of documents for notaries, and representation in mediation,

is provided by civil society organizations, mediators, and

notaries.

- The Ministry of Justice is responsible for maintaining a

registry of legal aid providers and decides on appeals against decisions

of municipal legal aid services. The bar chambers submitted a

list of 3,213 lawyers as legal aid providers to the registry, and 155

municipalities registered legal aid providers. In addition, two civil

society organizations are registered as free legal aid providers. In the

group of providers of legal support, there are mediators (45), notaries

(17), and civil society organizations (30).

The municipal legal aid services are responsible for the call center

used for refereeing citizens to lawyers and ensuring equal distribution

of cases among lawyers. In 2020 the Ministry of Justice ruled on 116

appeals against decisions of municipal legal aid services, and most of

them were for non-response from a municipal legal aid service (78) and

rejection of a request for free legal aid (31).

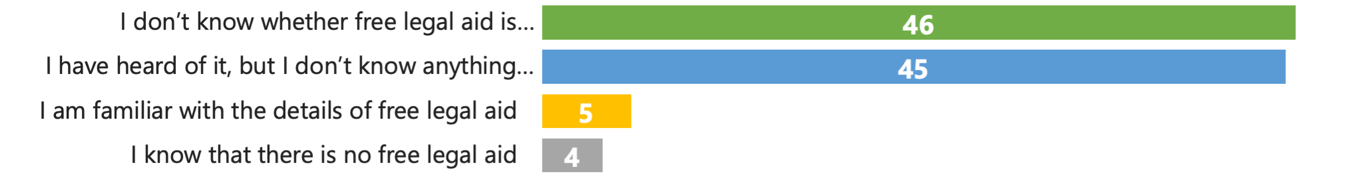

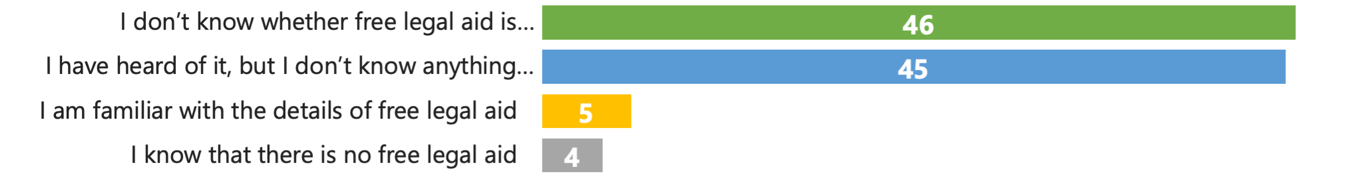

- Public awareness and knowledge about free legal aid is

limited, and most citizens are unaware of any free legal services that

might be provided. Only five percent of the general population

is familiar with the details related to free legal aid. In the 2020

Regional Justice Survey, 46 percent of respondents indicated that they

do not know whether free legal aid is available or not, while a similar

percentagee knew that free legal aid exists but have no specific

information regarding it. Citizens who have had recent court experiences

are more likely to be familiar with free legal aid (12percent), compared

to those without any experience with courts (4percent).

Figure 106: Citizens Knowledge about Free Legal Aid

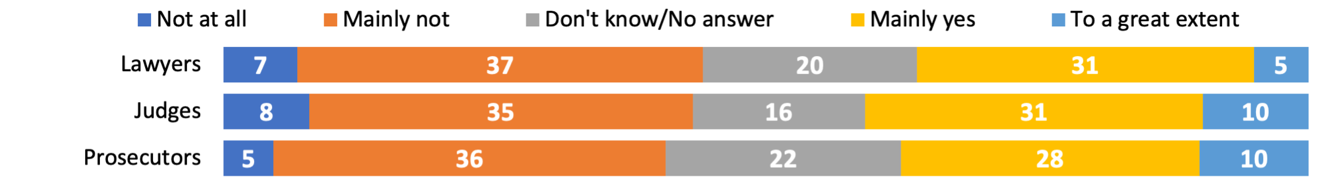

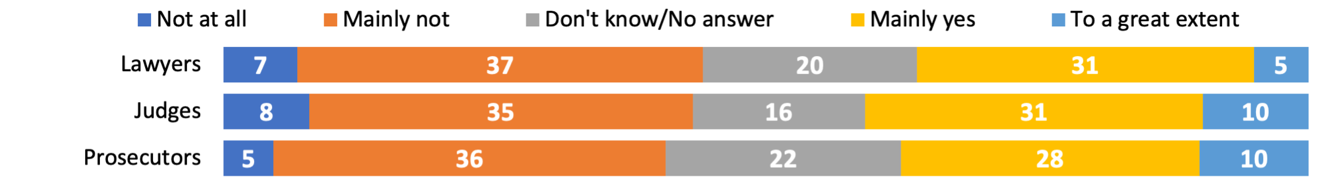

- Judges, prosecutors, and lawyers believe that legal aid

is not available to those in need. More than forty percent of

judges, prosecutors, and lawyers perceived that free legal aid does not

adequately reach the categories in need, while a significant percentage

of service providers claim to be unable to evaluate the accessibility of

free legal aid because of a lack of information.

Figure 107: Judges, Prosecutors and Lawyers: Availability of Free

Legal Aid

- Based on the Ministry of Justice's annual report on the

implementation of the Law on Free Legal Aid in 2020, advisory

services were provided 19,395 times, general legal information was given

in 9,745 instances and 1,913 written submissions were provided. In 2020

there were 6,883 requests for free legal aid, from which 5,367 were

approved, and in 954 cases, users were referred to a lawyer.

- Not all providers are submitting data to the Ministry of

Justice, which collates rates of use of free legal aid and types of

services, and the Ministry lacks resources to evaluate the

programs. Only one employee in the Ministry of Justice is

responsible for oversight of free legal aid implementation, including

field visits to the municipal legal aid services. Satisfaction with

services provided is not tracked or assessed at a central level. The

only instrument for measuring users’ satisfaction is a complaint

submitted against a lawyer.

Box 20 Law on Free Legal Aid:

- The Tariff Schedule for free legal aid introduced

significantly lower fees for lawyers than paid in other cases.

For example, under the free legal aid Tariff Schedule,

the cap a first-instance criminal proceeding for crimes up to 5 years of

imprisonment is 60,000RSD while under the general Tariff schedule

lawyers' fee is 22,500RSD for a motion in

criminal proceedings.

- Funding for legal aid is provided by the state

budget. The costs of the legal aid

provided by municipal legal aid services are covered by the local

self-government budget, while costs for services provided by lawyers,

notaries, and mediators are covered 50 percent of the local

self-government budget and 50 percent of the budget of the Republic of

Serbia.

- Effective implementation of the Free Legal Aid Law is

hindered by a lack of proper budget planning and a shortage of funds in

municipalities’ annual budgets. In addition, some

municipalities do not keep a registry of free legal aid, which impacts

the monitoring of implementation. Furthermore, the Ministry of Justice

has recognized the challenge of unifying the practice of municipal legal

aid services to ensure equal access to justice for all

citizens.

Access to and Awareness of

Laws ↩︎

- Access to and awareness of laws, a pre-requisite to

access to justice, is still limited in Serbia. Prior to 2014,

the only legal databases where statutes in their complete form were

available were those established and maintained by private companies for

an annual membership of approximately 500EUR.

On January 1, 2014, the Official Gazette (Sluzbeni Glasnik) launched its

online database where all legislation, including regulations adopted by

bodies other than the National Assembly, are available. This database is

partially publicly available for free (only selected laws and bylaws),

while full access requires payment of annual membership of approximately

340EUR. The National Assembly publishes

legislation only as adopted without inserting changes in existing

statutes. Ministries and other institutions that can adopt regulations

do not always publish them.

- 2020 Regional Justice Survey results suggested that

one-third of citizens perceived access to information, including access

to laws, as a challenge. People often do not

know where to find regulations and miss practical information concerning

their rights or procedures for their protection.

- Frequent changes in legislation undermine individuals’

access to justice, an issue recognized by lawyers as a significant

challenge. More than 40 percent of lawyers claimed that access

to information is limited. Judges and

prosecutors acknowledged to the Review team that they, too, struggle to

be up to date with the constant amendments.

- Free access to practical guidelines, authoritative

interpretations, and commentaries following new legislation is still

limited. Where they exist, useful commentaries on legislation

by relevant experts are not available to free of charge.

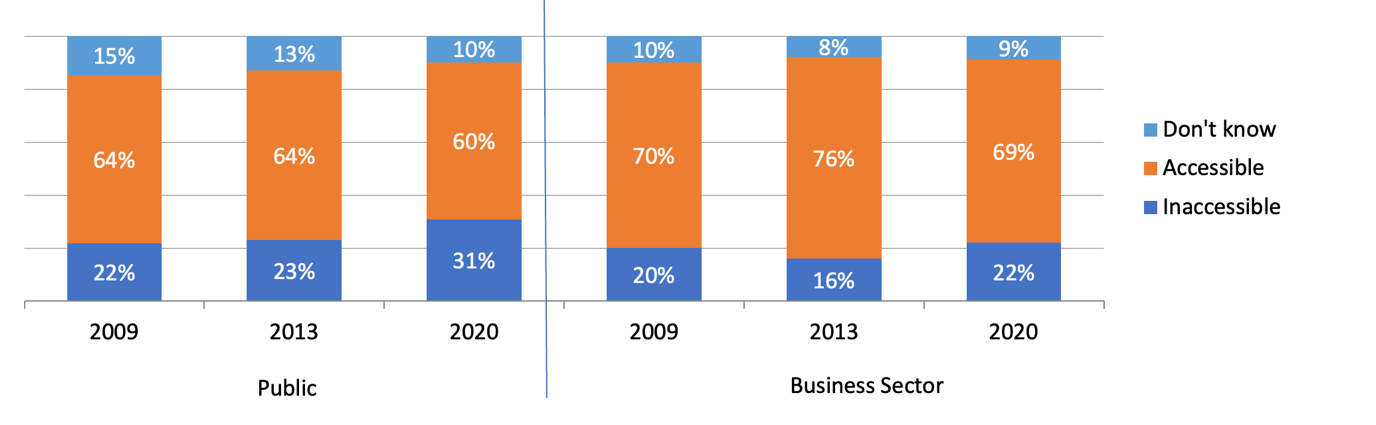

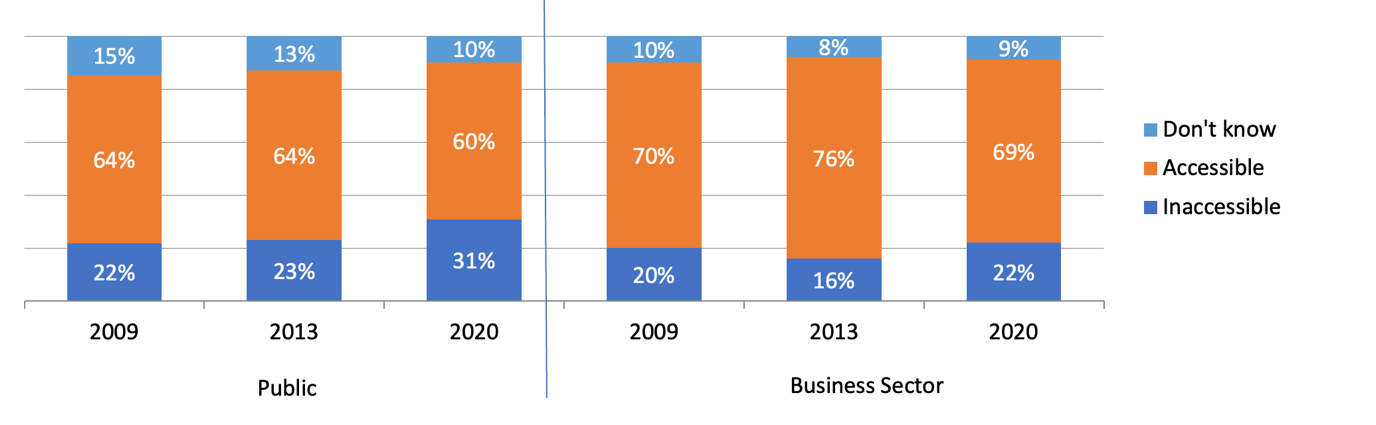

- In the 2020 Regional Justice Survey, compared to 2009 and

2014, a lower percentage of citizens and business representatives report

that specific court and case information is accessible (see Figure 108

below). 60 percent of the public and 69 percent of business

sector respondents reported that the judicial system is accessible in

terms of general access to information, compared with 64percent and

76percent, respectively, in 2013.

Figure 108: Perceptions of Accessibility of Information among Public

and Business Sector 2009, 2014, 2020

- Access to information is perceived as more challenging by

highly-educated citizens than lesser-educated citizens. In the 2020 Regional Justice

Survey, 38 percent of highly-educated citizens expressed difficulty in

finding necessary information, compared to 24.8 percent of the least

educated. These results mean that highly-educated citizens have more

expectations related to the volume, type, and quality of available

information, while the less-educated citizens lack the computerization

to access needed information or that information is not provided at an

appropriate reading level. These possible interpretations should be

borne in mind when planning how to make information on procedures more

accessible.

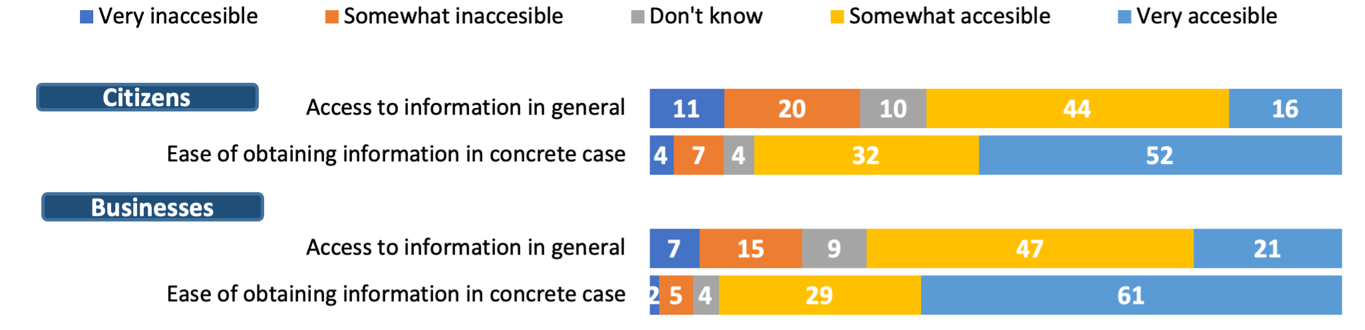

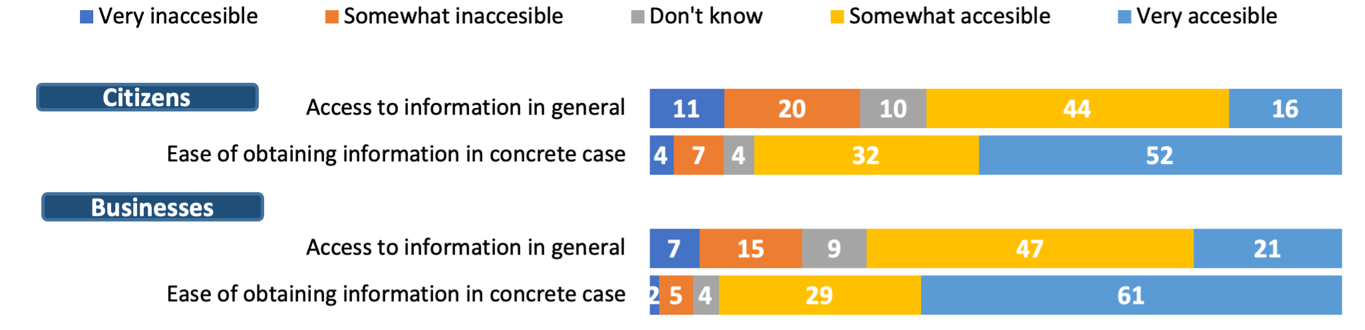

- Experience with court cases reflects positively on access

to information. Both citizens and businesses who had experience

with court cases reported higher satisfaction with access to information

in their specific case. 84 percent of citizens perceived access to

information in specific cases as positive, in comparison to 60 percent

of citizens who reported general satisfaction with access to information

from the justice sector. Businesses show similar patterns: nine out of

ten businesses who were involved in a specific case see accessibility

positively, compared to seven out of ten who did not have direct

experience.

Figure 109: Citizens and Business: Access to Information in General

vs Ease to Obtaining Information in Concrete Case

- Respondents use several sources of information when

looking for information about their case; in comparison to 2013, users

rely more on lawyers and official sources of information. This

varies in frequency depending on the type of case. In commercial cases,

lawyers are the most common source of information at 85 percent,

followed by official court information and then unofficial sources such

as friends, media, and the internet. A similar pattern holds true in

criminal cases, where lawyers are the prevailing source of information

(72 percent). In civil cases, lawyers and official court sources of

information are used most frequently (64 percent). Official sources of

information prevail in misdemeanor cases (95 percent), followed by

unofficial sources (41 percent).

Figure 110: Sources of Information Used for Case-Specific

Information

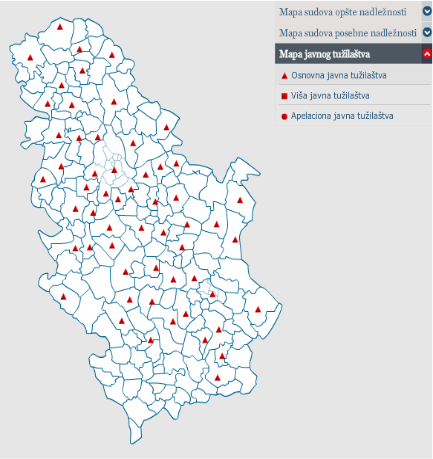

- Although there is progress in providing information

online, there is still room for improvement, which would enhance both

access and efficiency. All courts and prosecutor's offices have

websites. While prosecutor office websites are unified in visual design

and type of information provided, court websites still vary greatly.

Some courts have rich websites (for instance, the First Belgrade Basic

Court), while others do not have a website at all. Some NGOs also offer

useful, practical information. Providing online

information enables potential users to conduct research without

assistance, prevents unnecessary travel to the courthouse, and can

improve the efficiency of court processes. In 2020, internet penetration

in Serbia was approximately 80 percent,

and the Serbian judiciary should adjust to this.

- Availability

of court information and two-way communication with the courts both saw

significant progress with the introduction of a web portal Pravosudje

Srbije. The portal provides information on

the map of the courts with all relevant contact information, the status of ongoing procedures

by type of courts (basic, higher, appeal, commercial, misdemeanor,

supreme), including the status of cases managed by private bailiffs. Due to privacy constraints, the

portal can only be accessed by those who know the case number. Other

significant reforms included the development of the e-court, which

enables electronic communication with the court.

In addition, the Ministry of Justice developed eBoard, an electronic

notice board that became operational in January 2020

and replaced the previous physical notice boards in the courts in the

enforcement procedure. The web portal

Pravosudje Srbije includes a knowledge database

that provides general information on the jurisdiction of courts and

prosecutors’ offices, the obligation to testify, and family and

inheritance law. However, this information is not in a user-friendly

format and instead presents quotes from the legislation.

Access to Court Decisions ↩︎

- The SCC is still the only court that regularly publishes

all its decisions. However, the number of decisions available

online remains limited. Websites of the Appellate court in Novi Sad and Appellate court in Nis include a search engine that

enables easier access to the selected topic. The Constitutional Court

has made many of its decisions available online for the public. Other

courts do not regularly publish their judgments, although some, in

particular appellate courts, make some particularly important decisions

or excerpts from decisions available on their websites.

- The special website on court practice was developed in

2020. The website includes more than

12,000 decisions from the Supreme Court of Cassation, 45,000 from the

appellate courts, 5,000 from the Misdemeanor Appellate Court, 5,000

decisions from the Commercial Appellate Court, and 140,000 decisions

from the Administrative Court. The website includes a sophisticated

search engine that enables searching decisions by the court, year,

substance, registry, case number, president of the chamber, type of a

decision, etc. The decision of which cases to list on the court practice

website are made by court practice departments of the relevant courts.

The website was developed through project support and it needs to be

regularly updated with new decisions.

Access to Alternative

Dispute Resolution ↩︎

- Awareness of mediation is limited and is, in fact,

decreasing over time. According to the 2020 Regional Justice

Survey, only 14 percent of general court users and around 37 percent of

business users know what mediation is, and these levels are lower than

in the 2013 Multi-Stakeholders Justice Survey when 17 percent of

citizens and 53 business users were familiar with mediation.

Figure 111:Citizens and Businesses: Familiarity with Mediation

Process 2013-2020

- In May 2014, a new Law on Mediation was adopted by the

Serbian Parliament. The 2014 Mediation Law allows for parties

to be relieved from paying court fees if mediation is successful before

the end of the first hearing. Mediation may be used under the new Law in

any dispute unless a law stipulates the exclusive authority of a court

or other relevant body. In particular, mediation is seen as suitable for

property, family, commercial, administrative, environment, consumer, and

labor cases.

- The Law on Mediation introduced an obligation on courts

to promote mediation. The court is obliged to provide all

necessary information to the parties in a dispute about the possibility

of mediation, which can also be done by referring the parties to the

mediator. The Civil Procedure Code was amended in 2014 to include an

obligation for judges and courts to refer parties to mediation.

- Despite results showing that mediation is faster and

cheaper than a court proceeding, the Law on Mediation did not produce

its expected impact in terms of the number of issues handled.

In 2019 courts in Serbia managed 460,970 civil cases, while only 569

mediation cases were heard during the same year.

Research conducted with the EU for Serbia – Support to the Supreme Court

of Cassation project confirmed that first instance cases are resolved in

mediation in 53 days on average or 1/8th of the time of 414

days required to be resolved without mediation.

- Support for mediation by the Court Presidents is vital

for its success. Courts that were included in projects for the

promotion of mediation, like the Second Belgrade Court, the Commercial

Court in Belgrade, and Basic and High Courts in Cacak, established an

information service to provide information on the possibilities of and

procedures for alternative dispute resolution to citizens coming to the

court. Best practices were recognized and included in the 2017

Guidelines for Enhancing Use of Mediation in the Republic of Serbia,

adopted jointly by the Supreme Court of Cassation, High Judicial

Council, and Ministry of Justice.

- A case referral and registry for mediation cases is a

critical step to optimize the benefits of mediation and improve both

quality and efficiency in the courts’ performance.

Implementation of mediation in courts requires statistical monitoring

and reporting on mediation. This is difficult as mediation is still

registered in auxiliary books rather than the registry. A proposal of

the Forum of Judges to amend the Court Rulebook and introduce a special

M registry to track mediation cases could, by counting mediation as part

of the individual judges’ workload, incentivize judges to refer certain

types of cases to mediation. However, the

amendments to the Court Rulebook did not incorporate the proposed

measure.

Access to Allied

Professional Services ↩︎

- A vast array of professionals other than attorneys –

bailiffs, notaries, interpreters, expert witnesses, and mediators –

support the delivery of justice. Providing information about

these providers and ensuring they can be retained at a reasonable cost

is key to effective court access. Litigants need to be able to identify

these professionals easily by geographic area and topic area, understand

likely fees, and know if there are pending complaints against

them.

- The information available in registries varies in quality

and scope. The MOJ has created registries for most enforcement

agents, mediators, expert witnesses, notaries, and interpreters.

Interpreter and expert witness registries are available in Excel and

allow searches depending on the digital literacy of users. The registry

of bailiffs is also available on the website of the Chamber of Bailiffs,

and bailiffs are listed based on court seats,

as are notaries on the website of the Chamber of Notaries. The registries of bailiffs and

notaries are in a user-friendly format that enables easy search per

geographical location or court jurisdiction.

Geographic

and Physical Access to Justice Service ↩︎

Geographic Access to Court

Locations ↩︎

- Geographic barriers to access to justice are not a

significant concern in Serbia. Around 80 percent of citizens

and 89 percent of business representatives do not consider distance to

the courthouse to be a problem.

- As internet penetration improves, further expansion of

the court network becomes even more unnecessary. The

development of streamlined online processes can bring a range of court

services directly to the user. Future efforts to improve physical access

to justice services would be best addressed using online strategies,

such as e-filing.

Equality of Access for

Vulnerable Groups ↩︎

- Most citizens do not consider the judiciary equally

accessible to all citizens. According to the general

population, unequal treatment of the citizens is primarily based on

economic status and different political party membership. Almost half of

the citizens believe that degree of education impacts treatment by the

courts, while around one-third believe that ethnicity, sexual

orientation, and gender affect treatment. Age is mentioned as a reason

for different treatments by 28 percent of general users. Disability and

religious differences are mentioned by 22 percent of citizens.

Figure 112: Citizens Opinion on Equal Treatment of Citizens

- A considerably smaller percentage of judges and

prosecutors think that different categories of citizens are treated

disparately. However, 27 percent of judges and 31 percent of

prosecutors party membership as grounds for unequal treatment.

- The attitudes of lawyers regarding inequality of

treatment are considerably closer to those of the general population

than to the attitudes of providers of court services.

Figure 113: Judges, Prosecutors and Lawyers Opinion on Equal

Treatment of Citizens

- Members of the business sector also think that there is

disparate treatment of residents and legal entities. 57 percent

of representatives of the business sector believe the treatment of

economic enterprises depends on their ownership structure, and 47

percent think that treatment varies by size of the enterprise. Another

40 percent believe that treatment depends on the specific geographic

location in which the business is located, while 38 percent have

concluded it depends on the type of economic activity.

Recommendations and Next

Steps ↩︎

Recommendation 1: Accessibility of court fees.

- Update court fee schedules based on principles that ensure

affordability to file valid proceedings, discourage frivolous

proceedings, encourage alternative dispute resolution and settlement,

and ensure access to cases involving the public welfare, such as family

law cases. (MOJ, SCC – short- term)

- Amend the Law on Court Fees and Civil Procedure Code to state the

deadline for submitting requests for exemption from court fees and the

deadline for courts to decide on a request. (MOJ – short-term)

- Increase awareness that the court will not suspend litigation for

failure to pay fees. To safeguard against abuse of this policy, consider

requiring unpaid fees to be paid to the court till the end of the

procedure and extend the statute of limitations for court fees. (SCC –

short-term)

- Require courts to make an up-to-date online fee calculator

available to the public at no charge. (SCC – short-term)

- Develop a consistent and timely system for application for court

fee waivers. Evaluate whether the Central Application for Court Fees

(CSST), developed in 2020, is being used effectively, including its use

to track payments of court fees and information about fee waivers. (SCC

– short- term)

- Consider removing caps on court fees so that fees in high-value

cases are proportionate to those in lower-value cases. (MOJ, SCC –

medium-term)

Recommendation 2: Reexamine the affordability of attorney

fees.

- Consider alternative attorney fee arrangements under which

attorneys are not paid per hearing or motion. This will also incentivize

limiting the use of appeals and remands and improve case processing

efficiency. (MOJ, Bar Chamber – medium-term)

- Consider implementing practices used in EU member states and

other nations to negotiate attorney fees based on guidelines that

consider the value of the case, the amount of work required by the

attorney, and the public interest served by the case (for instance, more

strictly regulating fees for cases addressing child custody, injured

workers and people with disabilities, while allowing more arms-length

negotiation in cases of private interest). (MOJ, Bar Chamber –

medium-term)

Recommendation 3: Ensure access to and quality of ex officio

attorneys assigned to provide mandatory representation.

- Use the call center and tracking software introduced in 2019 by

the Bar Association of Serbia to collect data on the number of

appointments, the number of rejections of assignments and the reasons

given, and the types of cases where ex officio appointment is most

common. (MOJ, Bar Chamber – short-term)

- Monitor the work of ex officio attorneys to ensure quality and

impartiality. (MOJ, Bar Chamber – medium-term)

Recommendation 4: Increase public awareness of and access to

free legal aid.

- Encourage Community Service Organizations to refer clients to

Free Legal Aid Centers. (MOJ – continuous)

- Encourage law faculties to contribute their time and supervise

their students in providing Legal Aid services. (MOJ, Law faculties –

continuous)

- Adopt proper budget planning and increase funds for free legal

aid in municipalities’ budgets. Require all municipalities, Legal Aid,

and Legal Support centers to keep a registry of their activities and

submit data to the Ministry of Justice. (MOJ, MDULS –

short-term)

- Develop a method for tracking user satisfaction, implement it

locally, and evaluate results centrally. Provide the Ministry with

additional staffing to monitor the programs. (MOJ – medium-

term)

Recommendation 5: Increase access to information about laws

and courts.

- Consider having public libraries subscribe to online databases of

legislation and regulations so that the public can have full access

without charge. (MOJ – short-term)

- Improve the general public's access to published court decisions

and associated searchable databases. (MOJ – medium-term)

- When publishing new legislation, track changes and

cross-references to existing legislation. (National Assembly, line

ministries – short-term)

- Increase the public’s access to practical guidelines and

plain-language explanations of the law. (National Assembly, line

ministries – short-term)

- Require ministries and other institutions that adopt regulations

to broadly publish them (All – short-term).

- Continue to improve websites that provide information about

courts and particular cases. (MOJ, SCC– medium-term)

Recommendation 6: Increase access to alternative dispute

resolution options.

- -onduct additional outreach initiatives to potential court users

about the possibility of mediation. (MOJ, SCC – short-term)

- Provide additional training for judges, prosecutors, lawyers, and

court staff on the role of mediation. Consider using the best practices

recognized in the 2017 Guidelines for Enhancing Use of Mediation in the

Republic of Serbia. (JA – short-term)

- Adopt a case referral and registry for mediation cases rather

than continuing to register mediation in auxiliary books. Adopt the

proposal of the Forum of Judges to amend the Court Rulebook and

introduce a special M registry to track mediation cases, which would

count mediation as part of individual judges’ workload and incentivize

them to refer more cases to mediation. (SCC – short- term)

2020

2020