Quality of Justice

Services Delivered

Key findings

- The Serbian judicial system continues to struggle to

fully comply with ECHR requirements, as evidenced by the large caseloads

in Strasbourg. Non-compliance tends to be found in a

significant number of case types, highlighting specific problems

relating to non-enforcement of the final decisions, length of

proceedings, protection of property, and lack of effective

investigation. In addition, there are challenges in the enforcement of

ECtHR judgments, and further actions are needed to establish organized

coordination between all various state bodies.

- Overall, judges and prosecutors think that judicial

quality has improved since 2013, but lawyers see less

improvement. Unreliable data quality and availability,

inconsistency in jurisprudence, and fragmented administrative systems

are overarching challenges in addressing court system quality. On the

positive side, members of the public who have been involved in court

cases are generally satisfied with court quality.

- Citizens and the business sector are highly satisfied

with the quality of notary work, while there has been a decrease in

public satisfaction with court administrative services. While

most members of the public remain satisfied with the quality of court

administrative services, the downward trend in satisfaction should be

compared with positive public opinion about notaries. Part of the

courts’ administrative responsibilities was transferred to notaries in

2014, and public satisfaction suggests that the reform was

successful.

- There are some concerns about impartiality. These include

lawyers’ perceptions of selective enforcement of laws.

Prosecutors have complained the police do not cooperate with them during

investigations. Conversely, lawyers complain that they do not have

access to all the information that prosecutors and judges have. Further,

there is a concern that wealthier people may obtain deferred prosecution

by making monetary donations to good causes, and those decisions to drop

prosecutions are sometimes politically motivated.

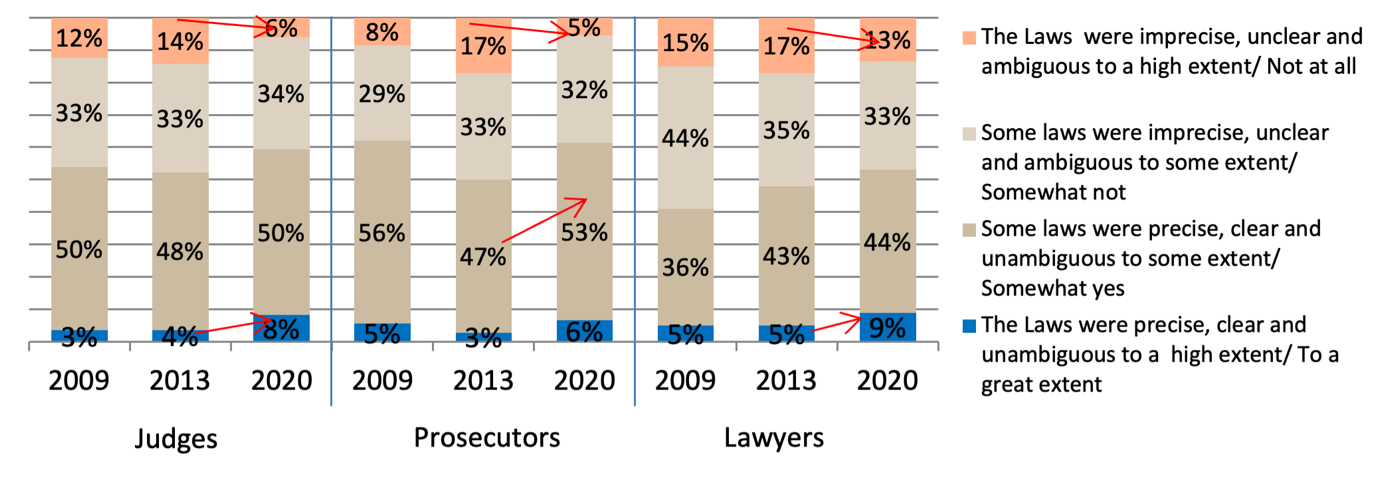

- Because of gaps and ambiguities in legislation, laws are

not applied consistently, and unwarranted appeals are filed, and,

conversely, lower court decisions are reversed on appeal. Two

related issues are the clarity of legislation and its application in the

judicial systems. Regarding the first, about 40percent of judges,

37percent of prosecutors, and 46percent of lawyers believe that laws are

ambiguous and inconsistent to a great extent or to some extent. While

lawyers’ perceptions have improved over time, there has been uneven

progress in judges’ and prosecutors’ perceptions.

- The proliferation of new legislation continues, often

without analysis of the impact on or harmonization with existing

laws. Ad hoc working groups are convened to consider and draft

each new law, but there is sometimes an inadequate representation of

stakeholders, working group members report inadequate guidance, and

proposals are not necessarily subjected to formal analysis. Legislation

continues to be routinely passed by the National Assembly under

emergency procedures and without sufficient transparency.

- 84 percent of judges cited that less frequent changes in

laws could contribute to a better quality of justice services.

Criminal prosecution provides an example of the impact of frequently

changed legislation and the quality of judicial services. The Criminal

Code was amended 10 times over the last 15 years. During this period of

change, offenses can be charged as both criminal and misdemeanor

offenses - or as both criminal and commercial offenses. The same

incident burdens the courts twice: once for the misdemeanor offense,

with its procedure and legal remedies, and again for a criminal offense

with its procedure and legal remedies.

- Following the enactment of new legislation, there have

been challenges in implementation. These include limited outreach and

training. A primary example is low awareness of the

availability of free legal aid (see Access Chapter).

- Inconsistent interpretation of laws and inconsistent

jurisprudence remain challenges for the Serbian judiciary. 70

percent of judges and prosecutors and 90 percent of lawyers stated that

inconsistent interpretation of laws and inconsistent jurisprudence

happen at least from time to time, if not often. More than 80 percent of

lawyers reported that selective implementation of laws and

non-enforcement of laws occurs frequently, but only about one-third of

judges and prosecutors shared this view. Judges’ and prosecutors’

perceptions have been slightly improved since 2013, but lawyers’

perceptions have worsened over the time, especially in the area of

selective enforcement of laws.

- The judicial system still lacks a standardized approach

to routine aspects of case processing. The quality of case

processing has not improved significantly since the 2014 Judicial

Functional Review. There are no checklists, standardized forms, or

templates for routine aspects of case processing, nor is there a

consistent approach to drafting routine documents, such as legal

submissions, orders, or judgments.

- There are few examples of specialized case processing for

the types of cases that often warrant a tailored approach. The

law on the prevention of family violence is an example of the potential

for improved coordination in case processing. It envisages the

establishment of a group for coordination and cooperation (Article 25)

that consists of representatives of public prosecutors, police, center

for social work, and, if there is a need representatives of other

institutions (educational, employment services, etc.).

- Lawyers who represent criminal defendants in particular

point to shortcomings in information and communication

technology. For instance, some databases are available only to

judges and prosecutors. There is no comprehensive countrywide system to

process and interlink cases across courts and prosecutorial

networks.

- There is a continuing lack of data about the reasons for

dismissals by prosecutors. Since 2013, Serbian law has allowed

the filing of complaints about the dismissal of criminal complaints, and

Serbians have made extensive use of this process.

- The number of cases concluded by plea bargaining

decreased by eight percent in 2019 due to a 17 percent drop in plea

bargains in the Belgrade appellate region.

- The implementing legislation for deferred prosecution is

incomplete and imprecise, prosecutors’ decisions are not uniform, and

guidelines and criteria for its use are missing. There is a

lack of consideration for the interests of the victims of the crimes

involved. The conditions imposed in deferred prosecution measures seldom

benefit the community at large through rehabilitation programs or

community service. The most frequent condition is a cash donation to

humanitarian causes. This can give the impression that defendants have

bought their way out of the criminal justice system.

- The lack of official guidelines and political will for

cooperation between police and prosecutors continue to impede the

effective investigation of criminal cases. Prosecutors have no

practical means for compelling police to follow their directions.

Prosecutors reported this problem arose particularly in cases that might

have political implications. In addition, when police submit both

misdemeanor and criminal charges for the same incident, they often do

not inform the prosecutor, which leads to duplication in court

proceedings, as noted above.

- Serbia’s prosecutorial system also remains highly

hierarchical, with higher-instance Public Prosecutors authorized to

control the work of lower-instance ones. Higher-instance

prosecutors can take over any matter from a lower-instance Public

Prosecutor within his or her jurisdiction and issue mandatory

instructions to those lower-instance Public Prosecutors. On the one

hand, such oversight could be useful in promoting consistent practices.

On the other, it may allow selectivity in prosecution.

- Standardized forms and templates used by PPOs are not

being updated on a system-wide and regular basis, despite amendments to

the criminal code. The use of up-to-date templates and

standardized forms would facilitate consistency in routine prosecutorial

tasks, reduce mistakes, and fast-track daily actions.

- The 2014 Functional Review found the appeals system is at

the heart of Serbia’s problems in terms of quality of decision-making

and remains high but has declined. The rate of appeals filed

and the rate of reversals on appeal, are relevant to legislative

quality, judicial quality, and public trust. A high rate of reversals

can indicate that lower courts are struggling to interpret ambiguous

laws. Lack of uniformity in the application of laws can encourage

parties to hope for a more favorable result on appeal.

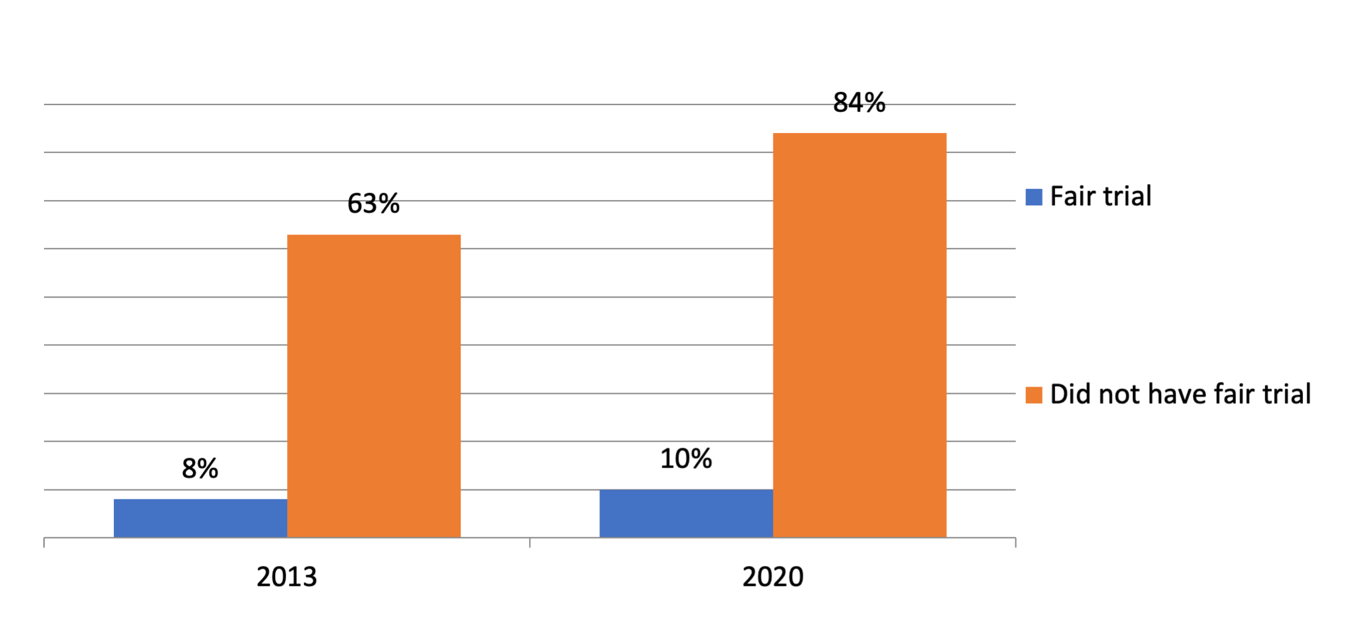

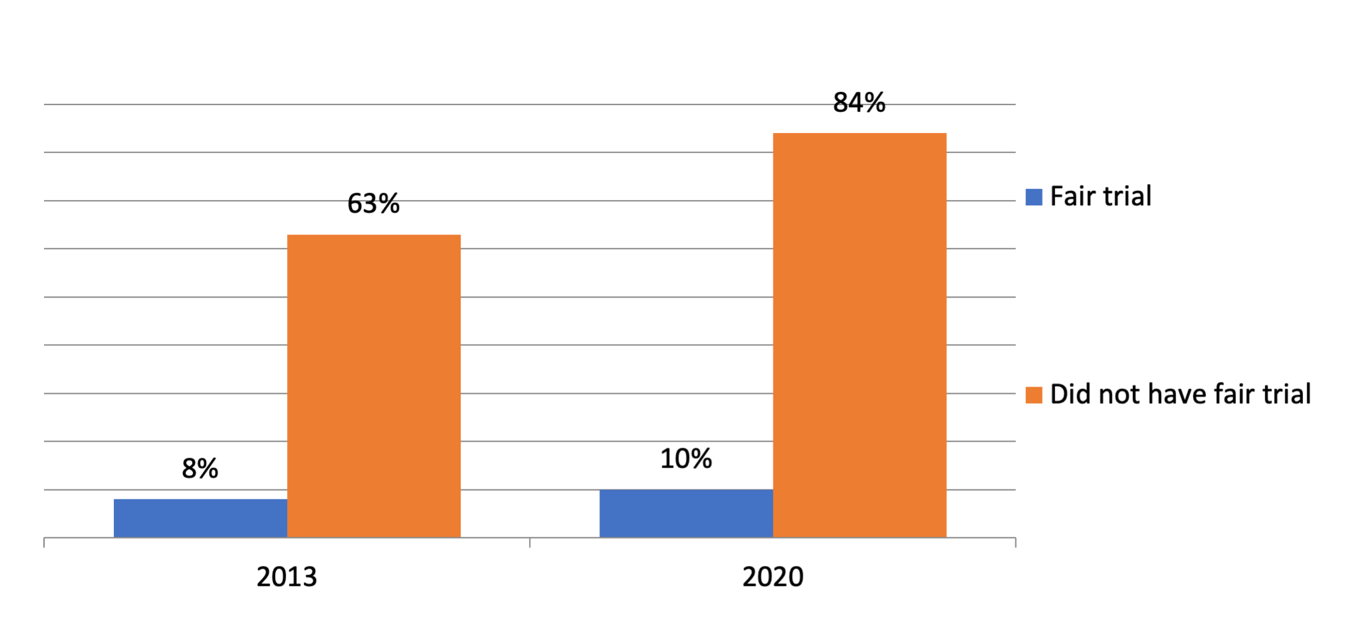

- Trust in the appellate system among court users in Serbia

has decreased in the past decade. However, Court users who

received an unfavorable judgment filed an appeal in 84 percent of the

cases if they considered the decision unfair, an increase by 21

percentage points over the 2014 Functional Review.

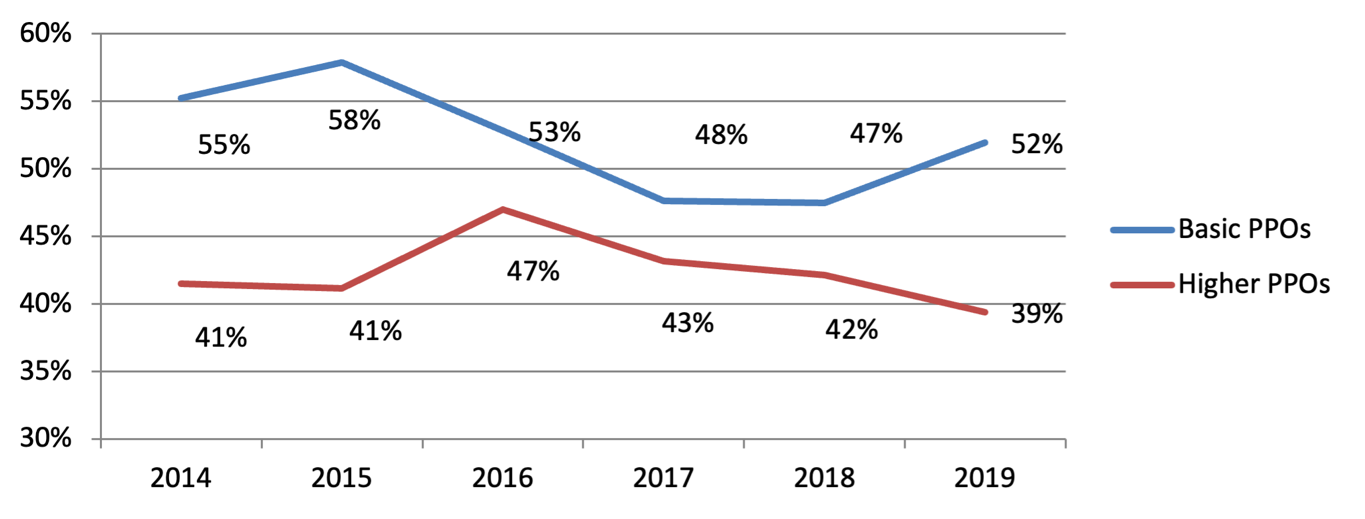

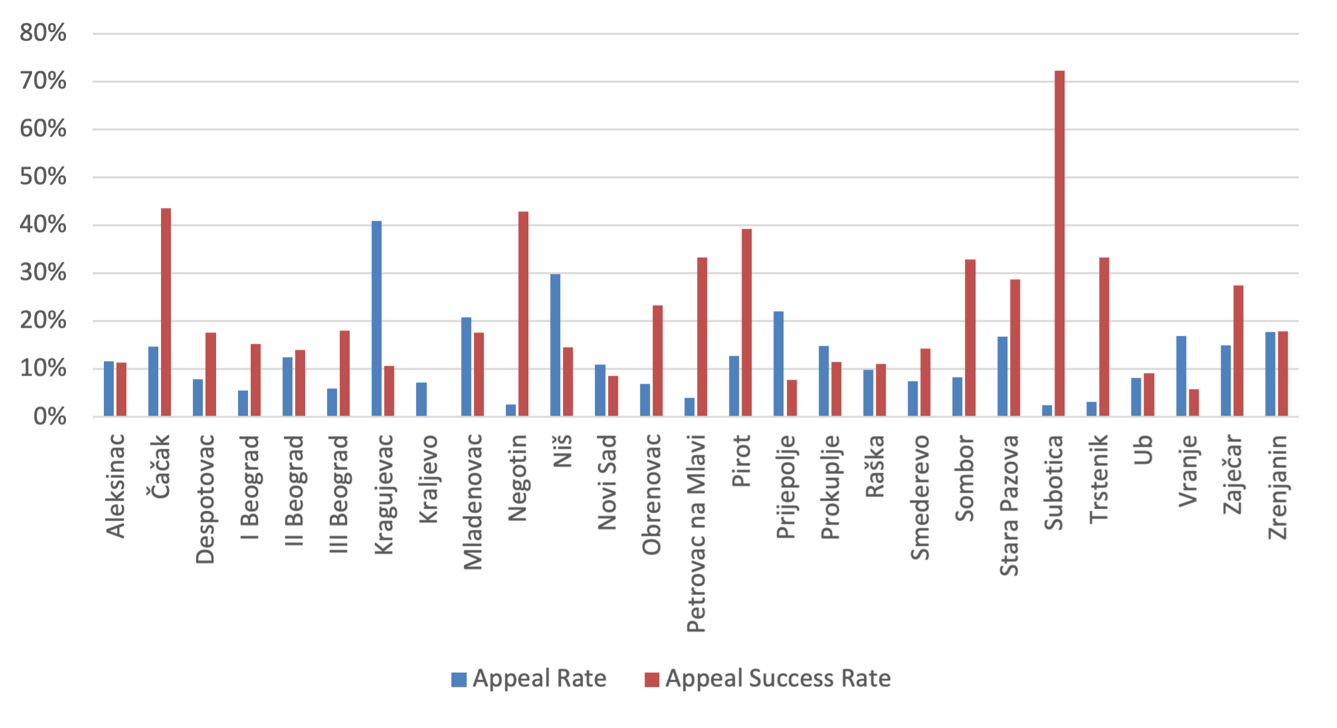

- Serbian Basic PPOs appealed in 12 percent of cases in

2019 and were successful in only 21 percent of their appeals, indicating

that prosecutors may be pursuing appeals that were not

justified. Appellate success rates varied significantly among

PPO types, among individual PPOs, and over the years. There were no

written policies or guidelines governing the selection of cases to

appeal. Appeal rates varied considerably among Basic PPOs, including

those of similar size.

- While appeal rates vary markedly across court types, case

types, and court locations, the data management system is not adequate

to compare performance. It is not possible to generate a report on

lodged appeals or dismissed appeals. It is not possible to

distinguish between cases appealed from Basic Courts and those appealed

from Higher Courts, which are entered in the same registry.

- It is possible that appeal and reversal rates will

decline as the quality of judges’ decisions improves. The

clarity in written decisions may help the parties, and the reviewing

courts better understand the reasoning of the first instance courts.

Existing judicial training has improved the clarity of written

decisions. The Supreme Court of Cassation has organized round tables to

discuss criminal judgments and identify shortcomings and good practices

in judgment writing.

- As well as improving quality, specialization can result

in more efficient use of limited resources. For example, the

courts are burdened with many repetitive cases that derive from the same

underlying issue. An example is over 56,000 military reservists’ claims.

Serbia has not adopted the practice used in some countries of

consolidating cases to resolve similar or identical factual and legal

claims.

Introduction ↩︎

- This chapter assesses the ability of the Serbian judicial

system to deliver quality services to citizens and its progress since

the 2014 Judicial Functional Review. Quality of justice

services was assessed through a range of dimensions, including the

uniform application of the law, user satisfaction with the justice

services received, consistency with ECHR standards, and perceptions of

integrity.

- The quality of the justice system is a significant part

of effective justice, underpinning business confidence, job creation,

and economic growth and providing protection from violations.

However, according to the World Bank 2020 Regional Judicial Survey, more

than 40percent of citizens and business representatives in Serbia

believe that the quality of the judicial system has not changed over the

course of the past three years, although many measures were implemented

with the aim of improving e the quality of work.

- In comparison to general perceptions about the quality of

judicial services, experience with court cases has a positive influence

on citizens’ assessment. Citizens with recent personal

experience are noticeably more positive about court work quality in

their own case (69percent) than is the general public (45percent). The

outcome of the case does not seem to play a role in the perception of

court work quality. At the same time, business representatives with

recent experience in court cases are the most satisfied with court work

quality. When court users do perceive low quality, they see bad laws,

followed by poor work by the judge, as the main reasons for the low

quality.

Quality of Laws and

Law-Making ↩︎

- The need to have good quality laws is stipulated in the

jurisprudence of the ECtHR. Therefore, the legislatures of

Member States need to respect the principles of the rule of law and the

minimum requirements of good law-making. This aspect includes

accessibility to information about laws and policies and foreseeability

about how they are applied. Otherwise, there can

be concerns about arbitrary interference by the public authorities.

- Clearly, the quality of justice depends on the quality of

laws and the performance of the law-making system. This section looks at three

dimensions of the quality of laws: perceptions of the quality of

existing laws, the law-making process, and the rollout of recent law

reforms.

Perceptions

about the Quality of Existing laws ↩︎

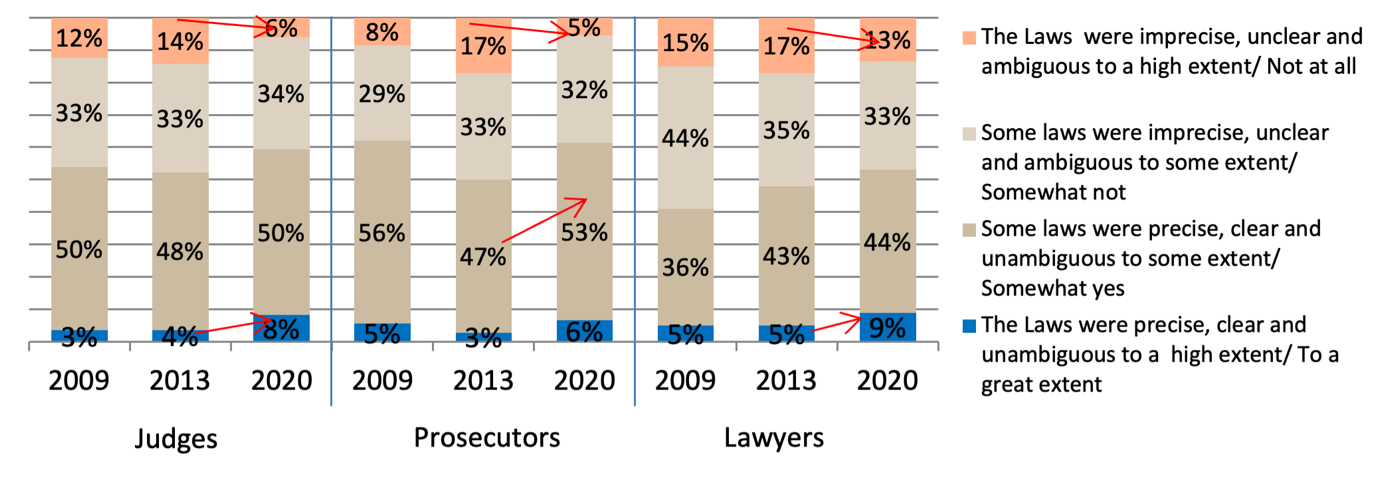

- Justice system professionals are concerned about whether

laws are clear and consistent. Among judges, 40percent believe

that laws are unclear and ambiguous to a great extent or to some extent.

Among prosecutors, 37percent share that view. Among lawyers, 46percent

have that concern, although lawyers’ perceptions have improved over

time. Judges’ perceptions of clarity of the laws fell between 2009 and

2013, then improved in 2019, but only back to the 2009 level.

Prosecutors’ perceptions fell between 2009 and 2013, then improved in

2019, but are still below the level in 2009. (See Figure 82)

Figure 82: Extent to which Serbian Laws are Clear and Unambiguous, as

Expressed by Judges, Lawyers and Prosecutors, 2009, 2013 and 2020

- Further, professionals expressed reservations about the

fairness of Serbia’s laws. Only 13 percent of judges and

prosecutors considered the laws to be generally fair and objective,

although these perceptions are an improvement in comparison to 2009.

Again, most professionals reported somewhere in the middle.

- The survey also highlights how imprecise and unclear laws

can impact the quality of justice services. Lack of clarity and

precision of the laws has a greater impact on the work of less

experienced judges. Compared to their older peers, 55 percent of whom

raise this issue, 69 percent of judges whose working experience does not

exceed five years point out the need for greater precision of the laws.

19 percent of lawyers and 9 percent of prosecutors cited unclear laws as

the main reason why the quality of judicial work is not higher.

- Improvement in the law-making process and less frequent

changes in legislation could enhance quality. 84 percent of

judges stated that less frequent changes in laws could contribute to a

better quality of justice services. In addition, 84 percent of judges

see a better quality of drafting legislation as a measure that would

improve quality.

- In interviews, stakeholders noted that overlapping and

conflicting laws cause problems for the courts. Several

stakeholders highlighted the need for greater harmonization of existing

laws, as well as the need to consider existing laws when drafting new

ones. Other stakeholders noted that there are gaps in the law, and that

judges struggle to deal with these cases in the absence of clear

guidance. Stakeholders in prosecution offices highlighted challenges in

the application of environmental protection legislation and the use of

ambiguous terms regarding wage laws, which causes problems in

interpretation.

Quality of the Law-Making

Process ↩︎

- Unfortunately, the quality of the law-making process is

still problematic in Serbia, despite the adoption of rules for the

preparation and adoption of laws. There are several problems

that lead to the adoption of laws of low quality. These include very

frequent use of urgent procedures for the adoption of laws, which

stifles democratic debate and lowers the quality of legislation; lack of

transparent and genuine debate; lack of strict rules on the membership

in working groups; and transposition of rules from other systems without

adequate assessment of conditions and their implementation in Serbia. Furthermore, the National Assembly

does not exercise its supervisory function, and changes in laws are not

based on an assessment of the impact on the practice or pre-existing

laws.

- Several stakeholders identified poor drafting practices

in recent years as contributing to unclear or ambiguous new laws, which

have led to uncertainty about the application of laws by the

courts. In addition, some changes to legislation were

introduced to improve practice, but without assessment of the impact of

previous laws and practice. For example, to address the risk of

corruption in the public procurement area, a special crime was

introduced in the Criminal Code – abuse in the public procurement

procedure. However, an insignificant number of cases have been

prosecuted under this law because public prosecutors have reported that

is more difficult to collect evidence for this crime than for abuse of

office.

- Organizational methods within working groups and

representation in working groups have not always been clear.

Stakeholders who are members of various groups expressed frustration

that working groups often are not given clear direction about the goals

to be achieved by the law and the specific mandate and methods for their

work. Some working groups are guided by prior analytic studies, but

others simply debate their views. Official working groups do not always

include representatives from the populations or entities with the most

expertise or those most directly affected by the legislation.

- Although there is a requirement to assess the financial

implications of proposed laws and institutional capacities to deliver

reforms, working groups do not always conduct such analysis in

detail. Lack of robust assessment of the financial implications

of the 2011 Criminal Procedure law, which entered into force in 2013,

led to significant financial arrears in public prosecutor’s offices.

- Although there are have been improvements in the

regulation of consultation processes and public debates, there are still

shortcomings. Amendments to the Law on Public Administration from 2018 brought some

improvements in the rules on public debate, such as the possibility of

opening a public hearing in the early stages of preparation of an act

(article 77), prescription of information that must be published before

a public hearing, and the obligation for public consultations during the

preparation of laws. The Government’s Rule of Procedure stipulates the

obligation to prepare a report on the public debate and publish it on a

webpage. In research on public debates held

in 2019, Transparency Serbia found that state administrative bodies did

not act the same way in similar situations and did not comply with the

provision of the Law on Public Administration and the Government’s Rules

of Procedure.

The Rollout of New Laws ↩︎

- Stakeholders still highlight concerns regarding the

successive and continual reforms in the law over the last

decade. Legislation is amended often without adequate

awareness-raising campaigns among practitioners and users. For example,

the Criminal Code was amended 10 times over the last 15 years, which

could cause confusion among practitioners and challenges in practice.

All that could lead to lack of trust and legal certainty, making it

difficult for potential court users to follow all those amendments and

to know what the law is.

- There should be a greater focus on the dissemination and

popularization of new laws, particularly given the pace of the reforms,

the limited consultation, and the emergency passage of laws.

Awareness of new laws is low among the public, court users, and even

among legal professionals (see Access to Justice Chapter and discussion

of awareness on Law on Free Legal Aid). Yet, they are the subjects and

actors in the new laws, and their understanding is needed for laws to be

implemented effectively.

Quality of

Administrative Services within the Courts ↩︎

- The level of satisfaction with administrative court

services is important from the perspective of court users because they

directly rely on such services to conduct their everyday

business. Administrative services to citizens and businesses

comprise 24percent of all administrative tasks within the court. Basic

Courts provide administrative services and issue certificates. Pending the appointment of

notaries for some municipalities, some courts continue to verify

signatures, manuscripts, and transcripts, including in probate

proceedings.

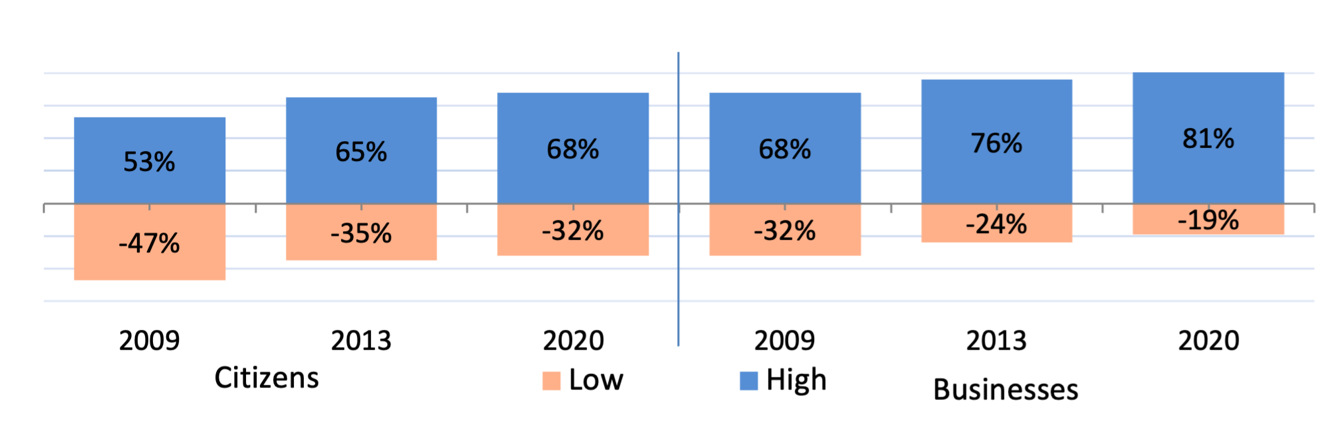

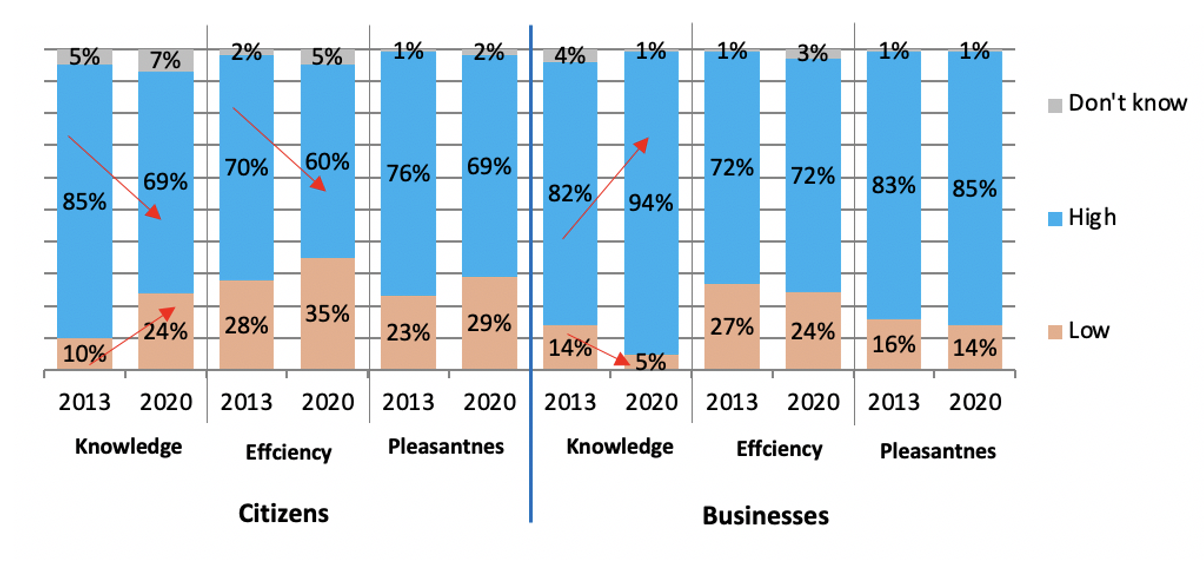

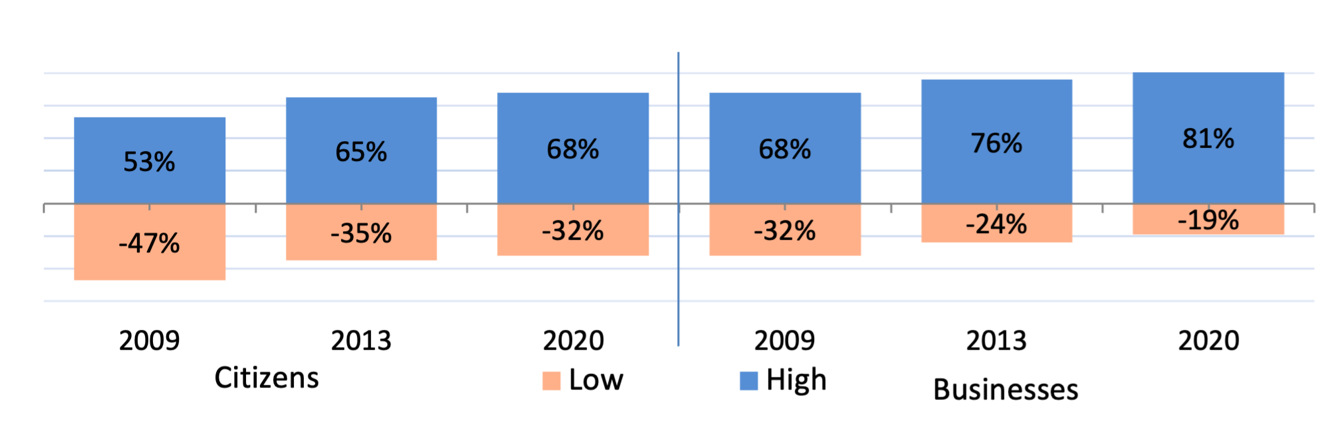

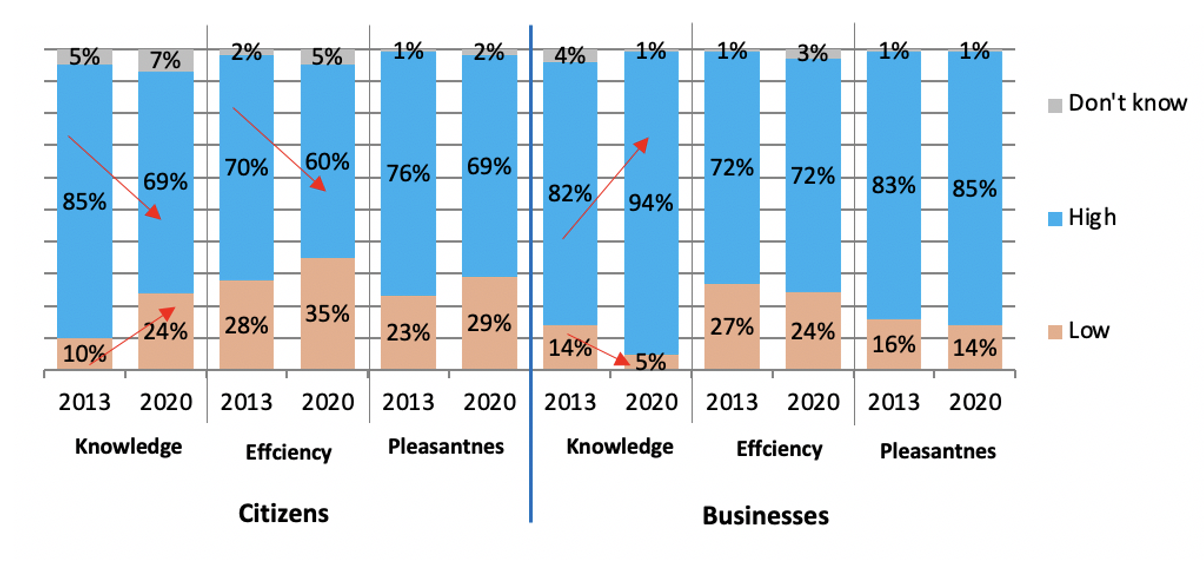

- According to the 2020 Regional Justice Survey, court

users assess the overall quality of administrative services to be

good (see Figure 83). Court users from

the general population and the business sector which had to complete

administrative tasks related to their court cases were more satisfied

with the quality of the administrative services than with the quality of

the court work related to their case.

Figure 83: Perceptions of Users of Court Administrative Service of

the Quality of Work in that Specific Administrative Case, 2009, 2013 and

2020

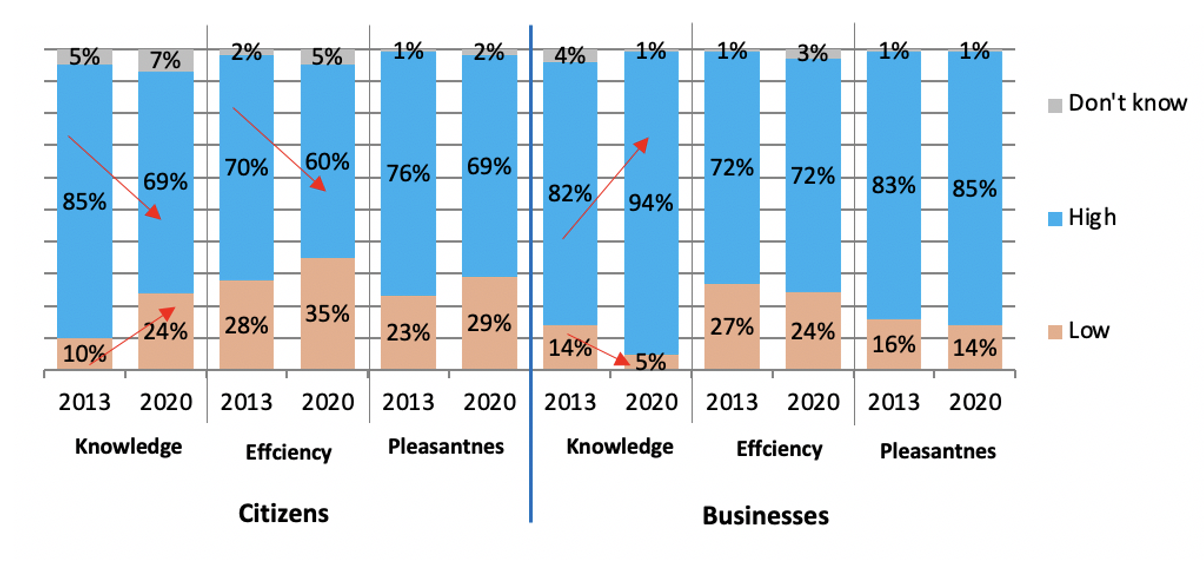

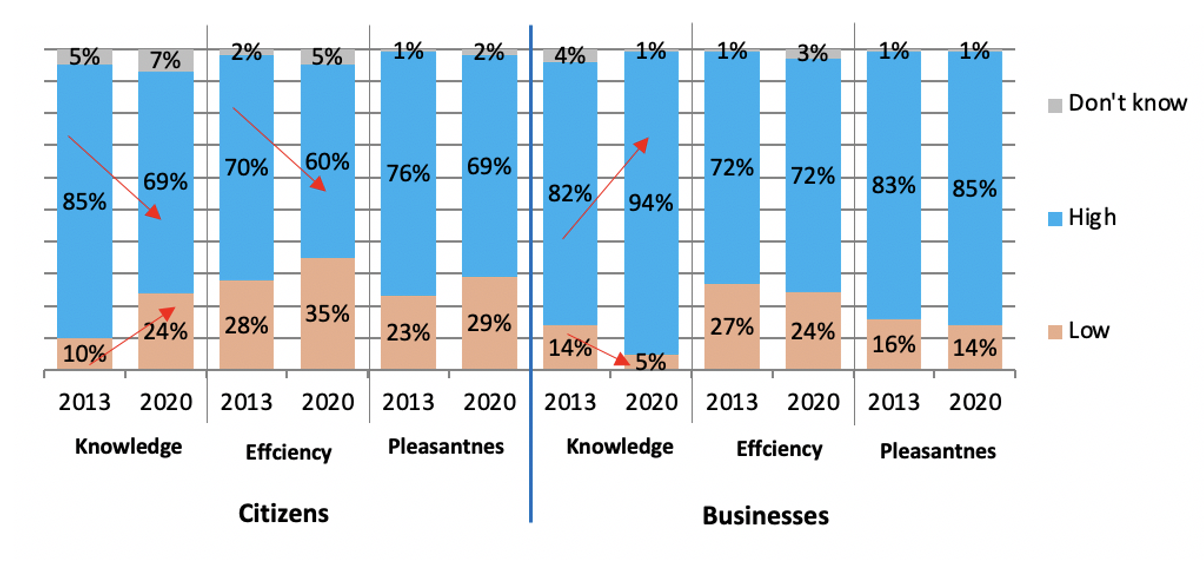

- The image of the conduct and competence of service

providers is worsening over time. Most users of administrative

services are satisfied with the knowledge, efficiency, and pleasantness

of staff. However, the number of dissatisfied users has increased over

the last seven years. Satisfaction with court administrative services

should be compared with satisfaction with the work of notaries to whom

part of courts’ administrative competencies were transferred in 2014.

Citizens and the business sector are highly satisfied with the quality

of notary work; 81 percent of citizens and 97 percent of businesses

reported being satisfied with the quality of notary work in their

specific case. Such high satisfaction confirms the success of that

reform.

Figure 84: Court User Perceptions of Efficiency, Pleasantness, and

Knowledge of Administrative Service Staff

Quality in Case Processing ↩︎

- The quality of case processing has not improved

significantly since the 2014 Judicial Functional Review. This

section reviews several indicators and European benchmarks relating to

the quality of case processing, including standardized forms,

consistency in the implementation of laws, use of specialized case

processing for particular case types, and coordination in case

processing.

- Consistency in case processing is still undermined by the

absence of a consistent approach to routine documentation.

There is no uniformity in the online availability of relevant templates

that could support users’ communication with the court and court

administration. There is no common approach, nor

have any changes been made by the Appellate Courts, SCC, or

HJC.

- The RPPO took some measures in the direction of

standardization to facilitate the application of the Criminal Procedure

Code. The RPPO provided standardized forms and templates in an

electronic format aligned with the new CPC in October 2013, but they

would benefit from a system-wide update now, after five years of

application. Prosecutors have altered some of the RPPO templates

themselves already. In addition, the OSCE issued guidelines for

different types of the prosecution to support prosecutors and provide

interpretation of provisions. However, to ensure

unified practice, it would be useful to issue a Guide by the RPPO as a

mandatory general instruction.

Consistency

in the Implementation of Law and Perceptions of the Quality of Judicial

Work ↩︎

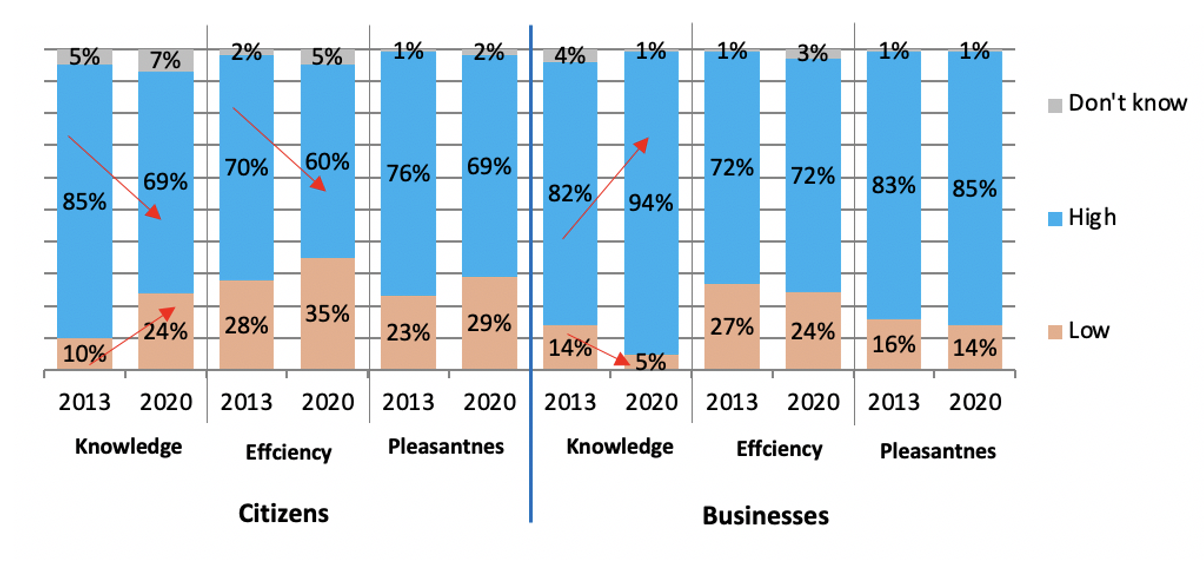

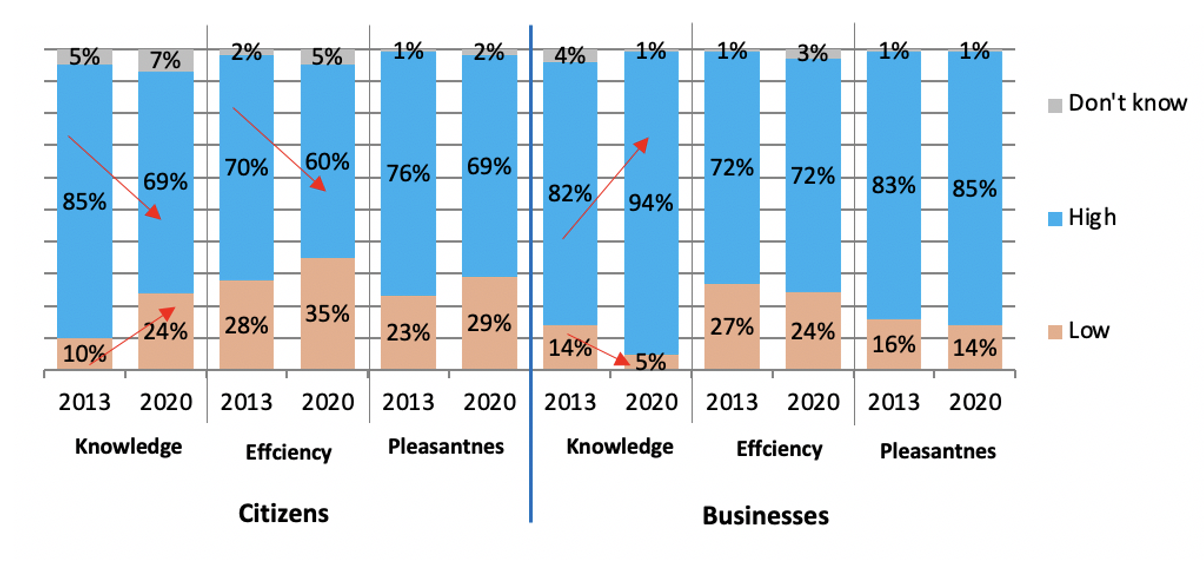

- Inconsistent interpretation of laws and inconsistent

jurisprudence remain challenges for the Serbian judiciary. In

the 2020 Regional Justice Survey, 70 percent of judges and prosecutors

and 90 percent of lawyers stated that inconsistent interpretation of

laws and inconsistent jurisprudence happen at least from time to time,

if not often. More than 80 percent of lawyers reported that selective

implementation of laws and non-enforcement of laws occur frequently.

However, only about one-third of judges and prosecutors shared this view

(see Figure 85). Judges’ and prosecutors’ perceptions have slightly

improved since 2013, but lawyers’ perceptions have worsened over time,

especially in the area of selective enforcement.

Figure 85: Share of Judges, Prosecutors, and Lawyers who Estimate

that Listed Problems Occur from Time to Time or Frequently in the

Enforcement of Laws, 2013 and 2020

- Despite improvement, lawyers are still mostly

dissatisfied with the quality of work of judges. By contrast, 73 percent of

prosecutors rated the quality of work of judges as high or very high in

2020, compared to 54 percent in 2014, and 67 percent in 2009. 87 percent of judges rated the

quality of judges as high or very high in 2019, compared to 50 percent

in 2014, and 61 percent of judges in 2009.

- The evaluation of improved quality over time is

substantially higher among judges and prosecutors (53percent of judges

and 48percent of prosecutors), than among lawyers (only

17percent). 42percent of lawyers actually report that the

quality has worsened over time, compared to only 7percent of judges and

15percent of prosecutors (see Figure 86 below). Lawyers’ opinions are

influenced by personal experience with the shortcomings of the existing

system, such as the lack of information and communication technology

systems, the absence of a comprehensive countrywide system to process

and link cases across courts and prosecutorial networks, and limits to

some databases, which are available only to judges and

prosecutors.

Figure 86: Quality of work over time

Use of

Specialized Case Processing for Particular Case Types ↩︎

- There are few examples of specialization in case

processing in the Serbian judiciary. Commercial Courts have

specialized their case processing somewhat. Misdemeanor Courts are a

type of specialized court, but within their jurisdiction is a broad

range of cases, from customs and tax offenses to traffic infringements,

yet few mechanisms exist to tailor case processing to these very

different types of cases. The Administrative Court has similar

challenges, with a broad range of cases ranging from competition cases

to cases related to election legislation.

- Lack of specialization prevents prosecutors from

developing special competencies and thus resolving cases with greater

success. In addition to specialized PPOs and four specialized

departments for corruption cases, only the larger PPOs have established

specialized departments. The First Belgrade PPO has departments for

commercial offenses and domestic violence, and the Belgrade Higher PPO

has a department for combating high-tech crime. On the other hand, there

is a specialization of case processing for juvenile cases in courts and

prosecutor offices as required by law.

Coordination in Case

Processing ↩︎

- Coordination in case processing still presents challenges

for the Serbian judiciary. Overlapping criminal and misdemeanor

offenses still exist in the Serbian legal system.

Elements of specific offenses can be charged as both criminal and

misdemeanor offenses - or as both criminal and commercial offenses. In Serbia, police often submit

both misdemeanor and criminal charges for the same incident and do not

inform the prosecutor of the duplication.

- Overlapping offenses also cause inefficiency within the

court system. The same incident burdens both the prosecution

and the courts - once for the misdemeanor offense, with its procedures

and legal remedies, and again for the criminal offense, with its

procedures and legal remedies.

- There are examples of the roll-out of good practices in

coordination of case processing across all courts. A positive

experience from inter-sectoral coordination in family violence cases

from Zrenjanin has been incorporated in legislation. The law on the

prevention of family violence envisages the

establishment of group for coordination and cooperation (Article 25)

that consists of representatives of public prosecutors, police, the

center for social work, and representatives of other institutions

(educational, employment services, etc.) if needed. The group is obliged

to meet once every two weeks.

- The great majority of prosecutors strongly believe that

cooperation with other investigative bodies contributes to the quality

of their institution, while judges and lawyers have more moderate

opinions on this issue. It seems that the view of prosecutors

is more accurate, and it is recommended that Serbia’s political leaders

implement an effective, no-tolerance policy for the unwillingness of

police to follow prosecutors’ instructions during all investigative

phases of a case. Otherwise, it will be impossible

to produce consistent improvements in the quality and timing of case

resolutions or increase public confidence in the judicial

system.

- Lack of political will, accompanied by the lack of

official guidelines, generally impedes the effective investigation of

cases. On the other hand, there are some

positive trends of cooperation that improve the quality of work. For

example, a cooperation agreement between Eurojust and Serbia entered

into force in December 2019, and in 2020 Serbia took part in three joint

investigation teams. Also, the cooperation between the

War Crimes Prosecutor's Office and the War Crime Investigation Service

has been improved by forming joint investigation teams and introducing a

new methodology. These positive examples of good

cooperation resulted in greater optimism among prosecutors who took part

in the Regional Justice Survey.

Quality of Decision-Making

in Cases ↩︎

- Although there is no template or a common approach to

judgment writing, some initiatives have been undertaken by the Supreme

Court of Cassation and professional

associations. The Supreme Court of Cassation

has organized round tables to discuss criminal judgments and to identify

shortcomings and good practices in judgment writing. The Judicial

Academy, in cooperation with the USAID ROL project, has organized

training for judicial assistants on judgment writing technics.

- Judicial training, both initial and continuous, includes

a judgment writing module. A judgment-writing component was

included in the Judicial Academy’s continuing training program for 2014,

but the training is general and does not teach a standardized approach.

As part of the initial training at the Judicial Academy, trainees

receive compulsory training on the writing of various types of judgments

and other court decisions in civil, non-litigious, enforcement, and

criminal cases; in their final evaluation as trainees, they are

evaluated on judgment-writing skills by their mentor judges.

Consistency of

Decision-Making with the ECHR ↩︎

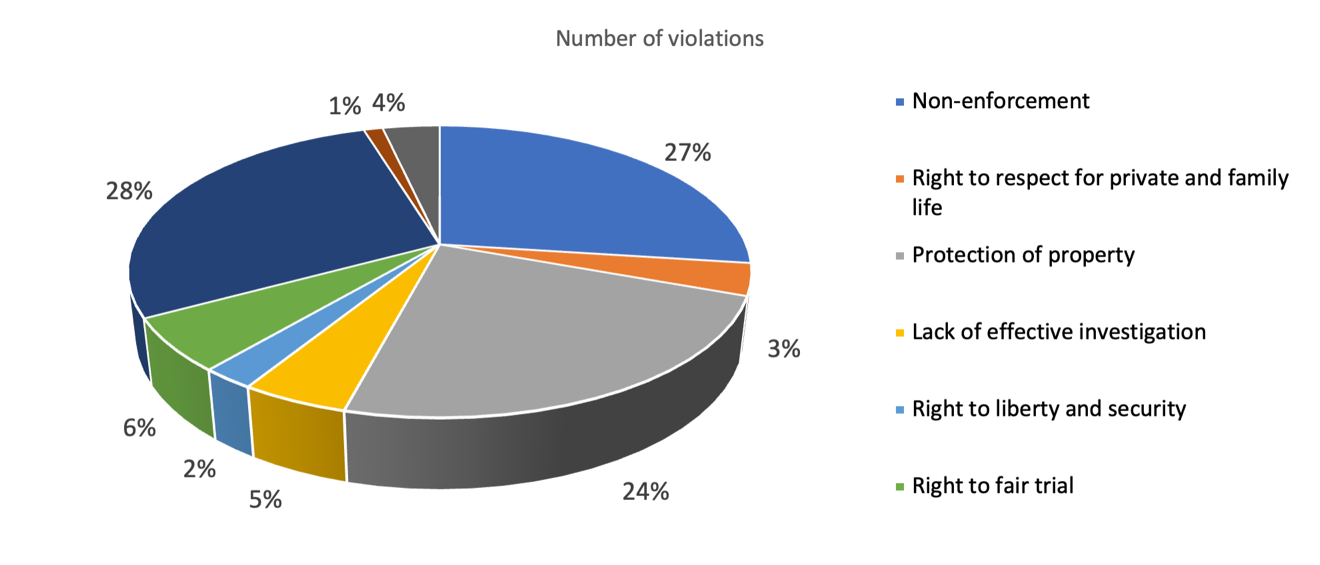

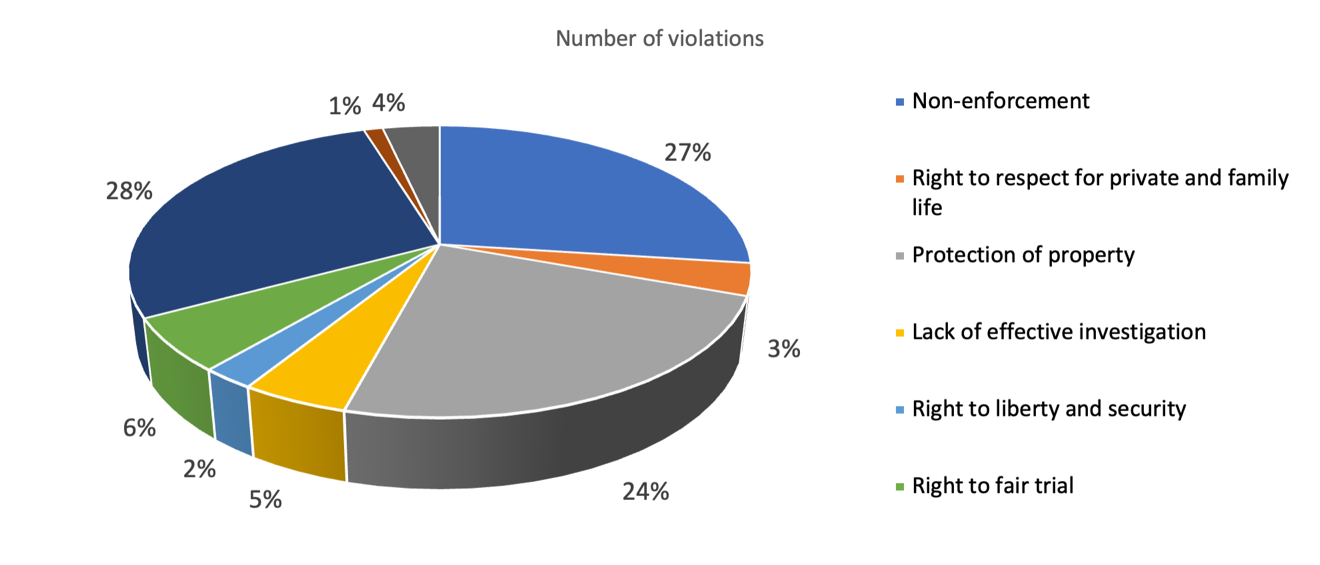

- The statistics of the ECtHR in Strasbourg suggest that

the Serbian justice system is still struggling to comply fully with the

standards of the ECHR. Between 2017 and

2020, there has been an increasing number of cases where Serbia has been

found in violation of the standards for non-enforcement and length of

proceedings. Compared to 2010-2013, the number of violations related to

the length of proceedings significantly increased, from 10 percent to 28

percent of overall violations, while violations concerning failures to

enforce final court decisions and non-enforcement remain high. Out of a total of 63 judgments in

2017-2020 in which the ECtHR found Serbia in breach of the ECHR, 28

percent of violations related to an excessive length of proceedings and

27 percent of violations concerned failures to enforce final court and

administrative decisions. Other violations were found for the right to

protection of property and right to a fair trial. Serbia also has been

cited for lack of effective investigation, inhuman or degrading

treatment, and the right to respect for family and private

life.

Figure87: ECtHR Judgments against Serbia by Case Type (2017-2020)

- There also has been an increase in the overall number of

Serbian cases pending before the ECtHR. Serbia is still among

the countries with a significant number of pending cases at the ECtHR

(2.8 percent of the pending applications at the end of 2020). This is only surpassed by far

larger countries, such as Russia (22 percent), Turkey (19 percent), and

Ukraine (16.8 percent). Almost 97 percent of the Serbian cases heard by

the ECtHR have been declared inadmissible or stricken.

- Of applications decided by a judgment, a significant

number have found at least one violation of articles of the ECHR (22 out

of 24 in 2019; 4 out of 5 in 2020). Among these, it is common

for the ECtHR also to find a violation of the length of proceedings and

non-enforcement.

- There has been a recent noticeable increase in the number

of friendly settlements, an effective way in which

Serbian authorities can resolve matters without the need for cases to go

to hearings.. In 2017, there

were 32 friendly settlements; by 2019, the number of settlements had

risen to 103, but this is still significantly lower than 679 friendly

settlements in 2013. The negotiation of friendly settlements is likely

to be a useful litigation strategy for the state, given that awards for

non-pecuniary damages can be quite high. Friendly settlements also are

good for applicants because they prevent further delay in resolving

their case and receiving compensation.

- The Serbian authorities are taking measures, both

legislative and non-legislative, to enforce ECtHR judgments, but certain

challenges remain. Cooperation among different state

authorities is the biggest challenge because enforcement of an ECtHR

judgment may include the adoption of legislation and change of court

practices and case law to come into line with the rulings of the ECtHR,

as well as having budgetary implications.

Therefore, it is important to establish organized coordination between

all relevant state bodies.

Effectiveness

of the Appeal System in Ensuring Quality of Decision-Making ↩︎

- The appeal system in Serbia remains one of the judicial

system’s impediments, with high appeal rates and deteriorating public

perception of trust. The system still provides only unprecise

data on lodged appeals, which hinders precise analysis and required the

FR team to use estimated figures. Rates varied noticeably across court

types, case types, and court locations. High appeal rates prolong the

overall duration of cases and increase caseloads. On a more positive

note, the reversal rates have declined and have been partially

substituted by increased amendments, most likely due to the legislative

obligation of the appellate court to decide on its own on the second

appeal.

- Ambiguity in laws and lack of uniformity in their

application may contribute to high rates of appeals and

reversals. Ambiguity may cause lower-court judges to make

reversible errors, while lack of consistency in lower courts may

encourage parties to hope for a more favorable result on appeal. Other

factors also may have encouraged parties to lodge appeals, such as the

attorneys’ interest in charging for more actions taken in a case and/or

dilatory tactics to postpone enforcement in adverse decisions.

Using

Data on Appeals to Evaluate the Quality of Judgments and of the Appeals

System ↩︎

- Due to the lingering lack of more appropriate data, this

FR, like the one from 2014, relies on an estimate of lodged appeals and

appeal rates. That is, present-day

reports still do not provide information on lodged appeals but only on

decided appeals, which does not necessarily equate to appealed lower

instance decisions made in the same reporting period. Also, as found in

the FR 2014, Appellate Court statistics still do not distinguish between

cases received from Basic Courts and cases received from Higher Courts.

Instead, cases deriving from both Basic and Higher Courts are entered

into the same registries.

- To calculate appeal rates, the FR team used the

number of resolved appeals adjusted by clearance rates of higher

instance courts. Since the clearance rates of all higher

instance courts examined here were close to 100 percent, the number of

resolved appeals should be reasonably similar to the number of lodged

appeals. This calculation is rather

straightforward for all court types except for Basic Courts, for which

the team needed to include an additional estimate to distinguish the

appeals disposed of by the Higher Courts from the ones disposed of by

the Appellate Courts.

- Serbian data on resolved appeals lacks one more dimension

– dismissed cases. The SCC’s reports disaggregate resolved

appeals by the following categories; confirmed, remanded, amended, and partially amended or

remanded. Dismissed appeals are left out, although they should be

reported as a separate category. Therefore, the FR team could not

include dismissals in its estimates. If dismissals were included, the

appeal rates would have been somewhat higher than estimated.

- Confirmation and reversal rates, without the appeal rate,

do not mean much individually, but they mean a lot combined.

High appeal and high confirmation rates in combination indicate stalling

or other abusive tactics by parties. High appeal and low confirmation

rates indicate quality and case law harmonization problems. The ideal

situation would be a low appeal rate and a 50 percent confirmation rate,

suggesting that only cases where even the judge may be uncertain of the

right outcome go to higher instances.

- Appeals are crucial not only as an indication of quality

in decision-making but also as a factor in efficiency and

timeliness. High appeal rates prolong the overall duration of

cases and increase caseloads. Reversal causes a case re-opening in the

lower instance court, after which the same case probably will be

appealed again. This could happen several times in a single legal

matter. However, procedural reforms have removed some of these

procedural loopholes. For instance, appellate tiers are required to

substitute the reversed decisions by their own judgments on the second

appeal.

Appeals by Court Type and

Case Type ↩︎

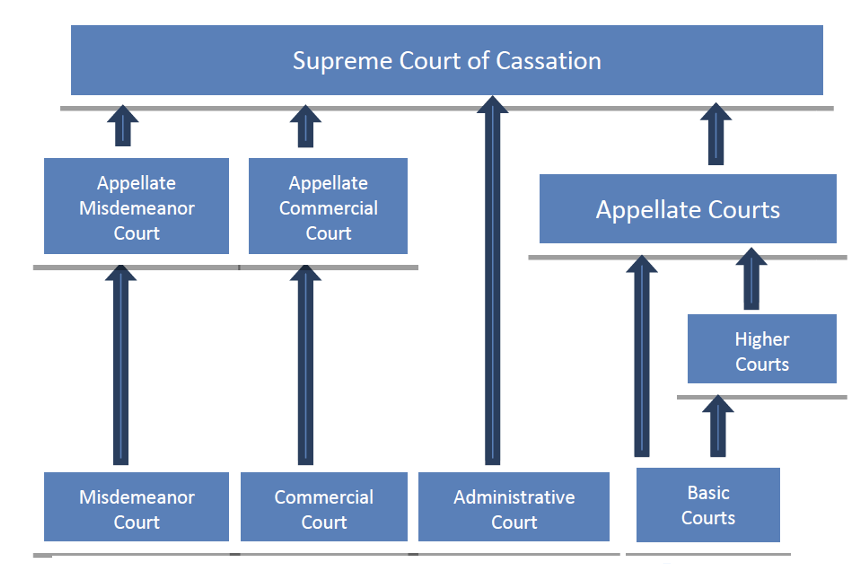

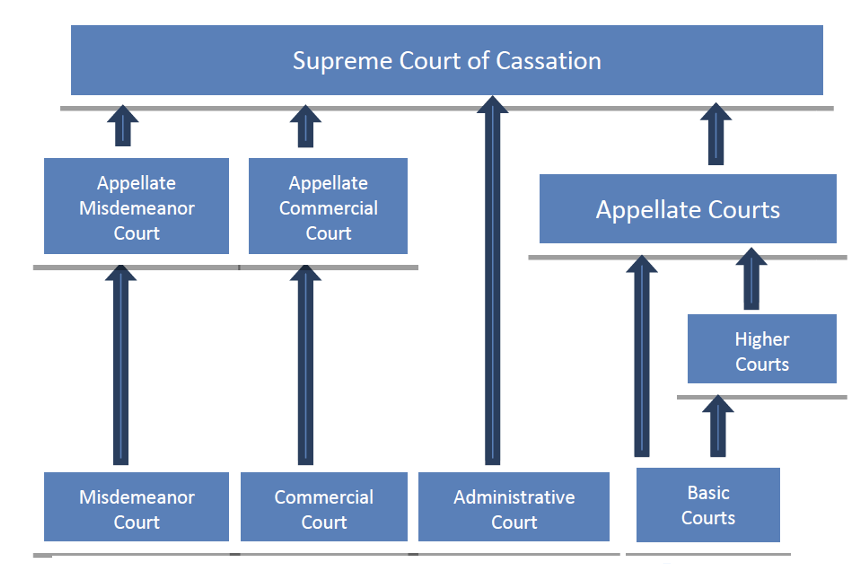

- There are four court types with appellate jurisdiction in

Serbia: the Higher Courts, the Appellate Courts, the Appellate

Commercial Court, and the Appellate Misdemeanor Court, in addition,

appeals may be made to the Supreme Court of Cassation (see Figure 88,

below). The ensuing analysis tracks appeals by court type and

offers views on the current state of the appellate system in

Serbia.

Figure 88: Court Appellate Jurisdiction in Serbia

Source: WB Team Illustration

Appeals from Basic Court

Decisions

- As a rule, appeals from Basic Courts go directly to the

Appellate Courts for review (so-called ‘big appellation’), but some,

usually concerning simple matters, are reviewed by Higher Courts

(so-called ‘small appellation’).

According to the data collected by the SCC for this FR, on a national

level, appeals against Basic Court decisions comprised 62 percent of the

Appellate Courts’ caseload in 2019, and 66 percent in the first half of

2020. Table 14 below displays ratios of received cases from Basic and

Higher Courts per Appellate Court in 2019.

Table 14: Received Cases in Appellate Courts from Basic and Higher

Courts in 2019

| Belgrade |

11,010 |

54percent |

9,558 |

46percent |

20,568 |

| Kragujevac |

8,764 |

66percent |

4,541 |

34percent |

13,305 |

| Nis |

8,313 |

67percent |

4,092 |

33percent |

12,405 |

| Novi Sad |

9,772 |

68percent |

4,704 |

32percent |

14,476 |

| TOTAL |

37,859 |

62percent |

22,895 |

38percent |

60,754 |

Source: SCC Data and WB Calculations

- The cumulative appeal rate of Basic Courts in 2019 was

nine percent – one percent higher than in 2013. This appeal

rate was calculated by dividing 105,464 resolved appeals in Higher and

Appellate Courts by 1,110,393 resolved cases in Basic Courts. 72.40

percent of the decisions or 76,356 were confirmed, 13.64 percent or

14,381 decisions were remanded, 8.18 percent or 8.622 decisions were

amended, and 5.79 percent or 6,105 decisions were partially amended or

remanded.

- Appeals against Basic Court decisions in civil litigious

cases in 2019 were high, with an

appeal rate of 30 percent or approximately seven percentage points more

than in FR 2014. Almost

three-quarters of the appeals pertain to general civil litigation (‘P’

registry) where the appeal rate in 2019 was estimated to be around 33

percent and the confirmation rate 72.64 percent. Labor civil litigious

cases (‘P1’ registry) occupied just under one-quarter of civil litigious

appeals, with an appeal rate of 43 percent and a confirmation rate of

71.72 percent. Family civil litigious cases (‘P2’ registry) comprised

three percent of the civil litigation appeals, with an appeal rate of

six percent and a confirmation rate of 59.10 percent.

- Appeals rates against Basic Court

decisions in criminal matters were also high at 24 percent. Interestingly, the appeal rate in

criminal matters appears to be stable over time, as it was only one

percent higher in 2019 than in 2013, as reported by FR 2014. Of appeal

decisions made in 2019, 68.79 percent were confirmed, 18.27 percent were

remanded, 10.50 percent were amended, and 2.45 percent were partially

amended or remanded. There were another two noteworthy categories of

criminal cases, so-called criminal panels (‘KV’ registry) and parole cases (‘KUO’ cases),

with appeal rates of 17 and 10 percent, respectively. In both

categories, the confirmation rates were almost 100 percent: 97.78

percent in criminal panels cases and 98.58 percent in parole

cases.

- Appeals against civil non-litigious cases remained low,

under five percent, and varied significantly among case types.

This is because non-litigious cases essentially do not involve a dispute

between the parties and because not all non-litigious decisions of the

Basic Courts can be appealed. On one side of the spectrum, the appeal

rate in probate cases in 2019 was 0.3 percent, and the confirmation rate

was 99.85 percent. On the other side, a 38 percent appeal rate was

reported in cases concerning requests for monetary compensation for

immaterial (non-pecuniary) damages due to violation of the right to a

trial within a reasonable time, while 94.49 percent of these cases were

confirmed.

- Appeals against enforcement decisions stayed very low at

approximately three percent.

Out of this percentage, 69.93 percent were confirmed, 12.64 percent were

remanded to the lower court, 11.98 percent were amended, and 5.45

percent were partially amended or remanded. Compared to 2014 data, the

number of amended and partially amended or remanded decisions increased

by multiple times, meaning that the higher instance courts now opt for

resolving the case by themselves more, rather than returning the cases

for retrial and prolonging their duration.

Appeals

from Higher Court Decisions to the Appellate Court

- In Higher Courts, a total of six percent of all decided

cases were appealed in 2019, approximately as many as in

2013. 77.33 percent were confirmed,

11.21 percent remanded, 8.42 percent amended, and 3.03 partially amended

or remanded. In comparison to 2013 figures, the confirmations have

increased by 11 percentage points, the remands have decreased by 3.5

percentage points, while the amendments and the partial amendments or

remands varied only slightly, up to one percentage point.

- Appeal rates among major case types in Higher Courts

varied significantly, primarily due to the ease of appeal. In

the first instance civil litigious cases, the estimated appeal rate was 20

percent, and the confirmation rate was 72

percent. Conversely, in the second instance civil cases, where there are very few

legislative options for appeal, the appeal rate was three percent, and the confirmation rate was

95.80 percent. By contrast, in criminal cases,

the parties appealed in 14 percent of the decided

cases, and the confirmation rate was 61.82 percent.

- In other case types in Higher Courts, appeal and

confirmation rates varied considerably. The lowest individual

appeal rate was 0.1 percent in cases concerning measures to ensure the

presence of the accused in the preliminary proceedings. The confirmation

rate for the same case type was 100 percent. In criminal panels cases,

the appeal rate was 28 percent, while the confirmation rate was 85.86

percent.

Appeals of Commercial

Court Decisions

- In 2019, the Commercial Courts, aggregate appeal rates

and confirmation rates were both moderate. Of the total of

140,082 Commercial Court decisions made, 15,242 were appealed to the

Appellate Commercial Court, representing around 11 percent of the

Commercial Courts’ decisions for that year. 75.37 percent of the

appealed decisions were confirmed, 11.30 percent were remanded to the

lower court, 9.24 percent were amended, and 4.09 percent were partially

amended or remanded.

- The Appellate Commercial Court displayed a greater

inclination to substitute the lower court decisions with its own, i.e.,

the remanded decisions decreased, while the amended and partially

amended or remanded decisions increased. In 2013 19.5 percent

of the decisions were remanded, which is 8.2 percentage points more than

in 2019. Conversely, the amendments increased by 3.44 percentage points

and the partial amendments or remand by 3.39 percentage points.

- Civil litigious cases in Commercial Courts reported very

high appeal rates of 39 percent, while their corresponding confirmation

rate was 73.71 percent. Out of 14,483 resolved cases, 5,721

were decided in the Appellate Commercial Court, and 4,217 were

confirmed. Similarly, high appeal rates were reported in Commercial

Courts in some case types involving bankruptcy proceedings

(reorganization plans) and in enforcement proceedings regarding the

right to a trial within a reasonable time.

Appeals of

Administrative Court Decisions

- In the Administrative Court, appeal and remand rates

remained low. In 2019, Administrative Court decisions were

appealed to the SCC in 1.5 percent of all Administrative Court decisions

for that year. This was a reduction by 2.3 percentage points compared to

FR 2014. Of the 329 appeals decided by the SCC in 2019, 91.08 percent of

the decisions were confirmed. This is almost exactly the same as in

2013, according to the FR 2014 data, when the estimated confirmation

rate was 91.11 percent. The latest data confirm the previous FR 2014

finding that there is a higher level of uniformity and consistency in

administrative law than in other fields and that a large number of

appeals are lodged without merit. However, this analysis is not able to

distinguish if the appeal rates were low, and the confirmation rates

high because the parties find it hopeless to go against the state in

administrative matters.

- Among individual case types in the Administrative Court,

the appeal rate is high (38 percent) only in cases concerning the right

to a trial within a reasonable time. Even in those cases, the

confirmation rate is also high, at 91.08 percent.

Appeals of Misdemeanor

Court Decisions

- In the Misdemeanor Courts, the aggregate appeal rate in

2019 was low, at four percent, while the remand and the amendment rates

were fairly high. In 2019, out of 614,246 decided cases, 25,539

decisions of the Misdemeanor Court were appealed to the Appellate

Misdemeanor Court. Of these, 58.78 percent were confirmed, 19.50 percent

were amended, 21.48 percent were remanded to the lower court, and 0.24

percent were partially amended or remanded.

- In comparison to the 2013 data analyzed in FR 2014, the

Appellate Misdemeanour Court doubled the number of amendments and

reduced the number of remands by roughly one-third. Almost

eight percentage points fewer decisions were remanded in 2019 than in

2013 (when 27.73 percent of decisions were remanded to the lower court).

At the same time, the percentage of amendments in 2013 (9.66 percent)

doubled to about 20 percent in 2019. Other categories are roughly

comparable to the 2013 data.

- The increase in the amendments and the decrease in

remands is an improvement in line with the FR 2014

recommendations. The FR 2014 argued that misdemeanor cases

should be relatively straightforward and the Appellate Misdemeanor Court

would be well placed to amend the decision and save the parties and the

Misdemeanor Courts the necessity of a retrial. The latest data indicate

that the Misdemeanor Courts complied successfully with the given

recommendation.

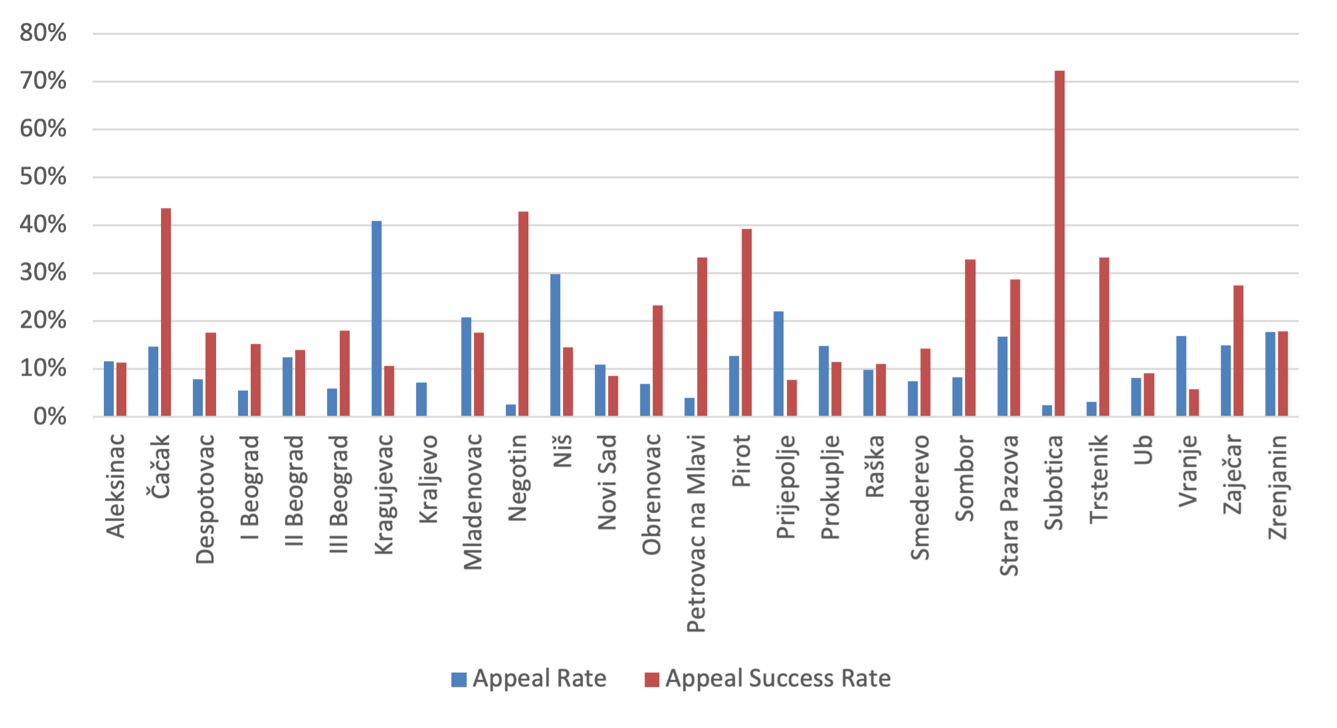

Appeals by Location ↩︎

- Outcomes of appeals varied among Serbian Basic Courts

without any clear pattern. The average reported confirmation rate was 68

percent. The Basic Court in Subotica reported the highest

confirmation rate in 2019 of 88.87 percent, while the lowest rate, of

34.18 percent, was reported in the Basic Court in Vrsac.

Simultaneously, the Basic Court in Vrsac also reported an unusually high

percentage of amended decisions – 57.02, primarily due to a very high

number of amendments of civil litigious cases registered under ‘P’.

Amendments were also high in Basic Courts in Sremska Mitrovica and Backa

Palanka, at 20.63 percent and 19.86 percent, respectively. By contrast,

the highest remand rate of 27.49 percent was reported in the Basic Court

in Bor, followed by the Basic Court in Velika Plana, Trstenik, and

Senta, in which over one-quarter of decisions were remanded.

Figure89: Appeals Outcomes in Selected

Basic Courts in 2019

Source: SCC Data

- Appeal outcomes varied also among Higher Courts but to a

lesser extent than in Basic Courts. The majority of Higher

Courts remained close to the average confirmation rate of 75 percent.

The only two true outliers were the Higher Court in Kraljevo, with a

confirmation rate of 34.64 percent, and the Higher Court in Prokuplje,

with a confirmation rate of 41.24 percent. In Kraljevo, the low

confirmation rate was caused directly by 59.75 percent of amendments of

406 labor civil litigious cases, most probably identical or very similar

disputes that could have been resolved uniformly. In Prokuplje, 36.60

percent of the decisions were remanded due to 47.90 percent or 57

remanded civil litigious decisions.

Figure 90:Appeals Outcomes in Higher Courts in 2019

Source: SCC Data

User Perceptions of Appeals ↩︎

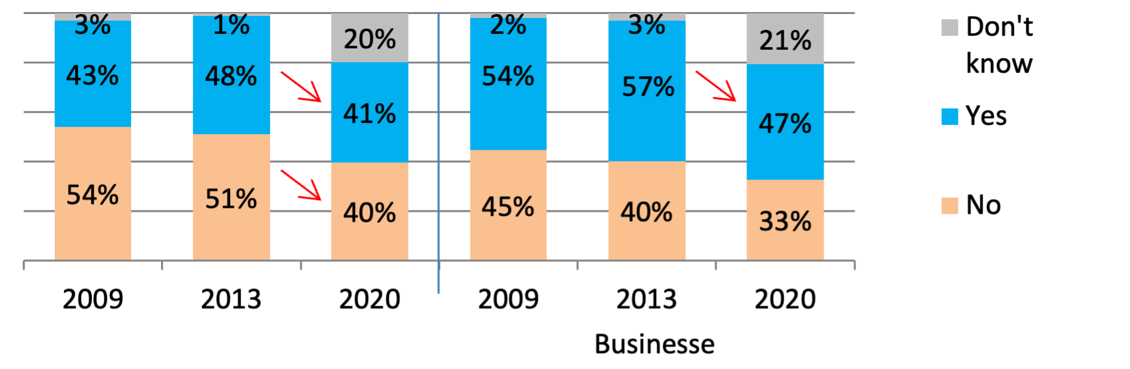

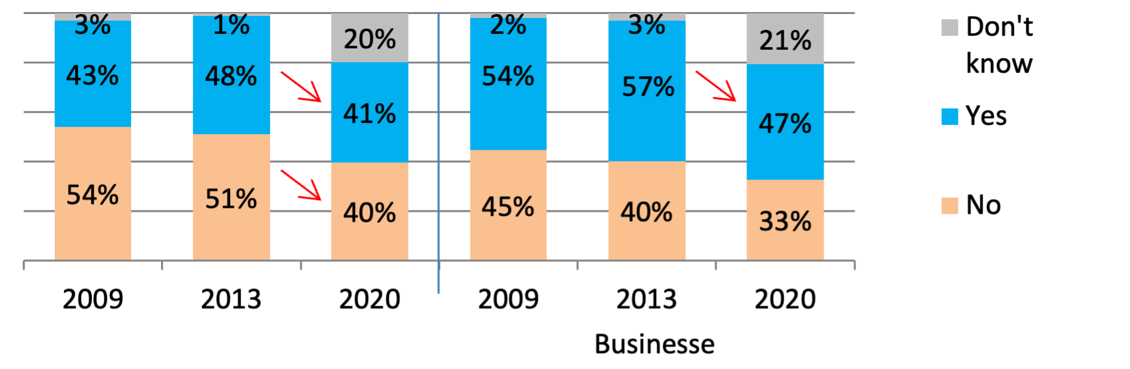

- Trust in the appellate system among court users in Serbia

decreased from 2013 to 2020, and fell below 2009 values, as demonstrated

in Figure 91. In 2020, under one-half (41 percent) of the

citizens with recent experience in court cases stated that they trust

the appellate system. Meanwhile, a slightly higher percentage (47

percent) of business sector representatives with court case experience

stated that they trust the appellate system. Interestingly, both the

number of people who stated that they trust the appellate system and the

number of people who responded that they do not trust the appellate

system decreased in comparison to both 2009 and 2013. The number of

indecisive respondents grew by seven to twenty times. It is unclear

whether this lack of trust in combination with indecisiveness,

encourages or discourages court users from lodging appeals.

Figure 91: Perceptions of Trust in the Appellate System, as Reported

by Court Users, 2009, 2013, and 2020

- The decision of a party to file an appeal remains

strongly related to the party’s perception of the fairness of the

first-instance trial, even more so in 2020 than in 2013. Court

users who received a judgment that was not in their favor filed an

appeal in 84 percent of the cases if they considered the decision to be

not fully fair, an increase by 21 percentage points over 2013. In

contrast, court users who received a judgment that was not in their

favor but who considered the decision to be fair appealed in only 10

percent of cases, an increase by two percentage points over

2013.

Figure 92: Relationship between Perceived Fairness and Decision to

Lodge Appeal among Court Users who Received a Judgment Not in their

Favor, 2013, 2020

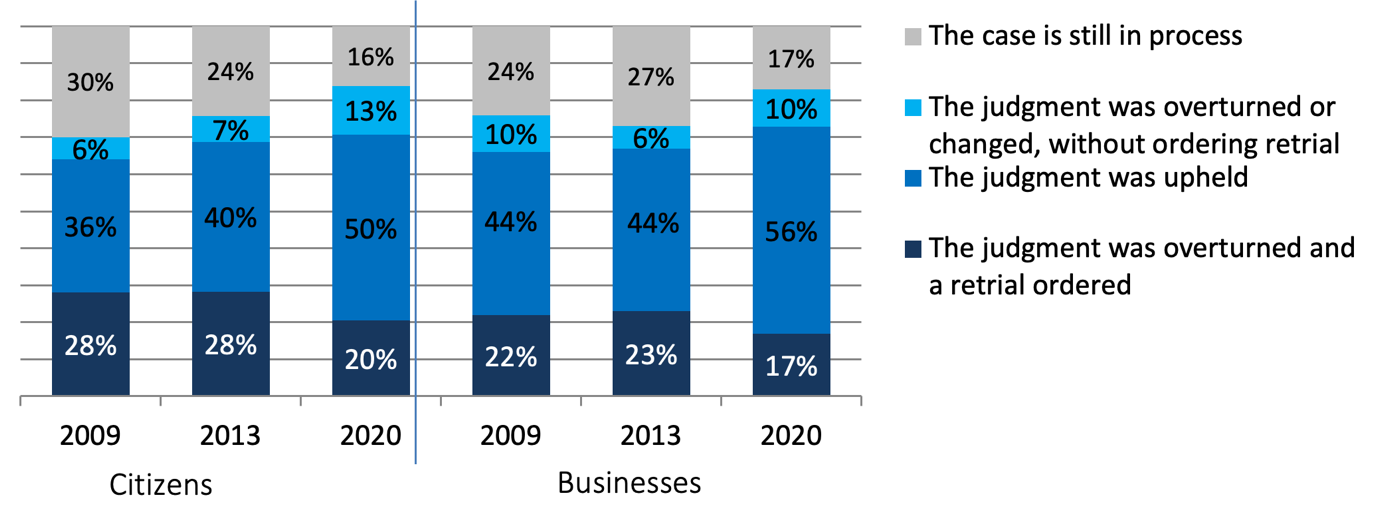

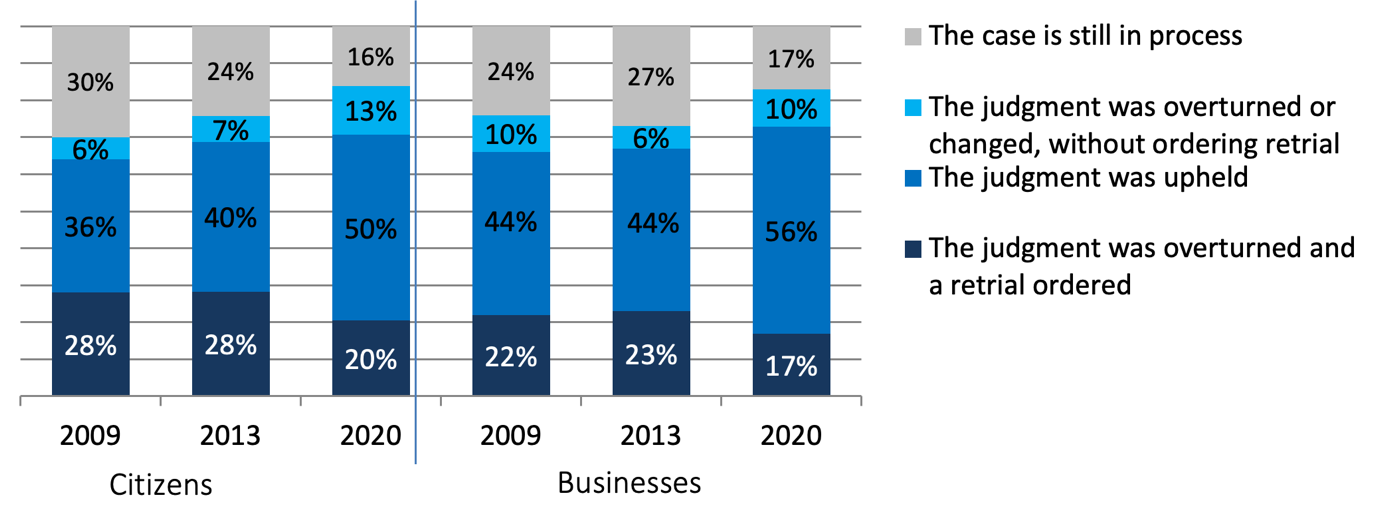

- In 2020, in over fifty percent of the cases, court users

reported that the higher instance court upheld the judgment.

However, in 20 percent of cases involving the public, the judgment was

overturned and a retrial was ordered. In 17 percent of cases involving

the business sector, the judgment was overturned and a retrial was

ordered. Simultaneously, the number of amendments increased from 2013 to

2020 in both citizens’ and businesses’ cases by six and four percentage

points, respectively.

Figure 93: Outcome of Appeals as Reported by Court Users, 2009 and

2013

High Appeal

Rates and High Variation in Appeals ↩︎

- High appeal rates in Serbia, particularly in specific

case types, and deteriorated perception of the appeal system suggest the

systemic presence of quality-related difficulties. Lack of

uniformity in the application of law may encourage parties to hope for a

more favorable result on appeal. Furthermore, it has been frequently

reported that attorneys also may play a role in driving up appeals,

since their expenses are predominantly calculated per each action they

take in a case. They also may instruct their clients about the

likelihood of success on appeal and the tactical advantages appeals may

offer, such as the delayed enforcement of an adverse judgment.

- Reasons for geographic variations remain inexplicable in

any way other than lack of uniformity in the application of the

law. Although one-time effects of specific circumstances in

courts, such as remands of many uniform labor cases, may cause sudden

variations, it is not likely that this could be the case in all of

Serbia, especially since the variations are persistent in 2013 (2014

Functional Review findings) as well.

- The FR 2014 found the appeals system is at the heart of

Serbia’s problems in terms of quality of decision-making.

Appeal rates were found very high on average, as were reversal rates.

Rates also varied markedly across court types, case types, and court

locations. Appeals were poorly monitored. The perceived unfairness of

the system, combined with its lack of uniformity and consistency,

encouraged court users to appeal. Attorney incentives were also

identified as one of the factors driving up appeals. At the same time,

levels of trust in the appellate system among court users were low.

Procedural amendments to reduce successive appeals (known as the

‘recycling’ of cases) were found effective. Nonetheless, appellate

judges (notwithstanding their lighter caseloads) continued to remand

cases back to the lower jurisdiction for retrial more often than they

were required to.

- On a more positive note, the higher instance courts more

often replaced the lower instance decisions with their own, as supported

by data earlier in this section. In FR 2014, only a small

percentage of cases were higher instance courts amending the decisions

of lower courts, although the benefits of such amendments are numerous.

They save the parties the trouble of re-litigating in the lower instance

court, ease the workloads of judges and courts, shorten the trial, and

increase uniformity in the application of the law over time. Legislative

changes obliged the higher instance court to replace the decisions with

their own on the second appeal. Higher instance judges should work

toward, whenever possible, replacing the decision of the lower court in

instances other than a second appeal in the same matter. Higher instance

decisions in which a reversal is issued should contain precise reasoning

and instructions to be followed by the lower court in subsequent

proceedings.

- A range of other measures are available to improve the

quality of decision-making. Some of them were already suggested

in the FR 2014. These comprise education of judges, better use of

existing case law harmonization tools, and implementation of new ones

(e.g., meetings of judges in the same department to discuss legal

issues).

Quality of prosecution ↩︎

Introduction

- This chapter builds on the analysis of Serbia’s

prosecutorial system (Prosecutorial FR) by the World Bank and the

Multi-Donor Trust Fund for Justice Support in Serbia, by examining data from

2017 through 2019. The Governance and Management Chapter of

this report covers those functions for the prosecution as well as for

the courts, but readers should consult the Prosecutorial FR for more

details about the structure and hierarchical nature of the prosecutorial

system overall. The Prosecutorial FR also covered the functions of the

SPC, the RRPO, and the different types and jurisdictions of

PPOs.

- The Prosecutorial FR, formally published in January 2019,

focused primarily on 2014 through 2016, when Serbia’s prosecutors were

adjusting to extensive changes in the nation’s Criminal Procedure Code

(CPC), adopted in 2013. These changes included the introduction

of adversarial proceedings, which challenged many prosecutors as they

adjusted to their new, more active roles.

- At the same time, leaders of Serbia’s political and

judicial systems were under continuous pressure to make major additional

structural changes to the governance and management of the country’s

prosecutorial functions as part of Serbia’s planned accession to the

EU. That pressure has continued to the publication of the

present FR, as discussed in the various EU reports related to the EU’s

Enlargement Policy.

- The official data on which many of the statistics in this

Chapter rely were not always consistent and could not always be

reconciled. Data in this study came from statistics in RPPO

Annual Reports from 2014 through 2019 and from the SPC, but other data

was derived from interviews and published analytical reports such as

those produced by CEPEJ.

- The available data for prosecutorial services still was

far less extensive than it was for courts, and the data that was

reported was of limited use because of the collection methods and

formats. There was no unified electronic case management system

for the prosecutorial system in place by the end of 2019. The available

RPPO Annual Reports were published in a format

that was not suitable for computer processing. Preparation of those

reports depended highly on manual data collection and individual

interpretation, which made the reports prone to inconsistencies and

inaccuracies.

Quality in Case Processing ↩︎

- There were no significant advancements in modernizing

performance measuring for prosecutors or PPOs. Prosecutors

still lacked support in measuring their performance and how to use this

information to their advantage to improve case management, support

funding requests, foster public support, and respond to criticism

clearly and precisely. The prosecution system would undoubtedly benefit

from such modernization.

- Regular system-wide updates of the standardized forms and

templates provided by the RPPO in 2013 were still required, especially

since there had been several amendments to the CPC since 2013.

Individual prosecutors reportedly altered some of the RPPO templates for

their own use, but there was no centralized revision of the official

forms. As noted in the Prosecutorial FR, the use of templates and

standardized forms facilitates a consistent approach to routine

prosecutorial tasks, reduces the number of mistakes in documents, and

fast-tracks regular daily actions.

Conviction rates ↩︎

- As important as they are for assessing the quality of

prosecution, conviction rates alone do not provide a complete picture of

how well any prosecutorial system has performed. In addition to conviction rates,

factors such as the timing and reasons for dismissals and deferred

prosecutions can be used to examine both the quality of decision-making

and the skills of professionals within a judicial system.

- The types of cases included in Serbia’s conviction rate

statistics did not change between the publication of the Prosecutorial

Functional Review and 2019, so they included only cases in which a court

entered a decision of guilty or innocent. As a result, the

statistics about convictions included cases concluded through plea

bargains but did not include deferred

prosecutions, which involve the dismissal of charges by a prosecutor

without a court finding of guilt or innocence, while imposing a sanction

on the defendant.

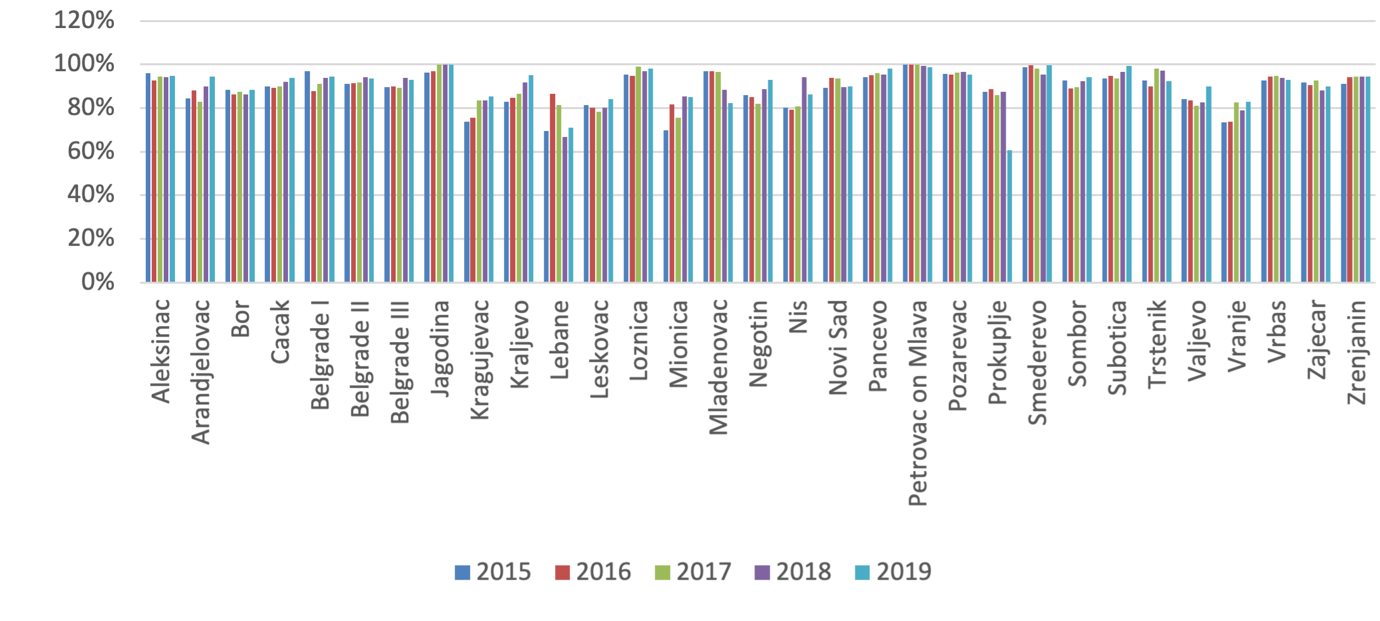

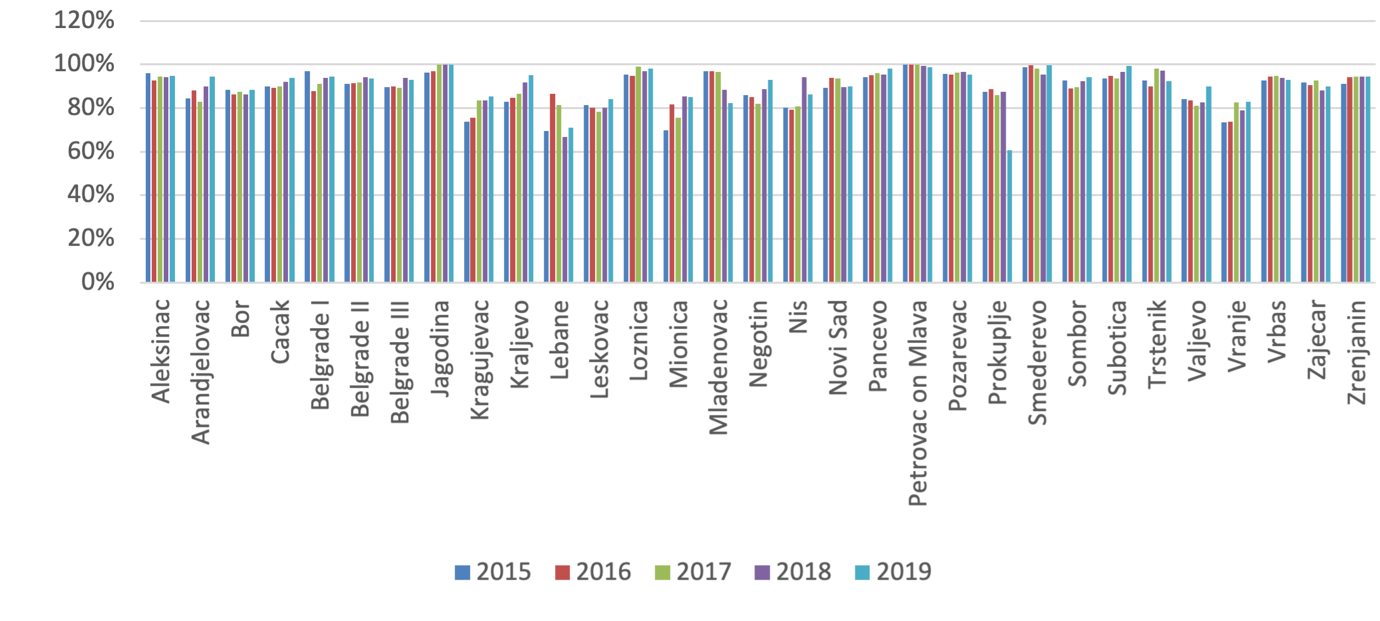

- The overall conviction rates of Basic and Higher PPOs

held steady or improved during 2018 and 2019, compared to the rates for

2015-2017. The average for Basic Courts was 91 percent for 2018

and 2019, compared to 90 percent for 2015-2017, while the average for

Higher Courts increased from 86 percent in 2015 and 2016 to 89 percent

in 2017 and 2018, and 91 percent in 2019.

- However, there were wide variations in conviction rates

among even PPOs of the same size and jurisdictional levels and sometimes

by year within the same PPO from 2015 through 2019. See Figure

94 and Figure 95 below. The FR team was not able to obtain any analyses

of the reasons for the variations that may have been completed by the

SPC or the RRPO. The Basic PPO in Petrovac on Mlava had

a 100 percent conviction rate from 2015 to 2017 and a 99 percent

conviction rate in 2018 and 2019. Similarly, high conviction rates

throughout the period were reported in Basic PPOs in Jagodina and

Smederevo. The Basic PPOs in Belgrade had rates that were roughly at the

national average. Conversely, similarly-sized Basic PPOs in Lebane and

Mionica reported much lower conviction rates and/or higher variations. . The medium-sized Basic PPOs in

Vranje had lower conviction rates than the average, ranging from 74

percent in 2015 to 83 percent in 2017 and 2019. The Basic PPO in Nis

improved its conviction rate significantly in 2018 to 94 percent, which

was approximately 14 percentage points higher than in previous years,

but the rate fell again in 2019 to 86 percent. In 2019, the lowest

conviction rate (61 percent) and a drop of 27 percentage points compared

to the previous year was reported in the Basic PPO in Prokuplje. This

sudden drop in Basic PPO in Prokuplje was caused primarily by a 400

percent increase in the number of acquittals.

Figure 94: Convictions for Selected

Basic PPO from 2015 to 2019

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2015-2019

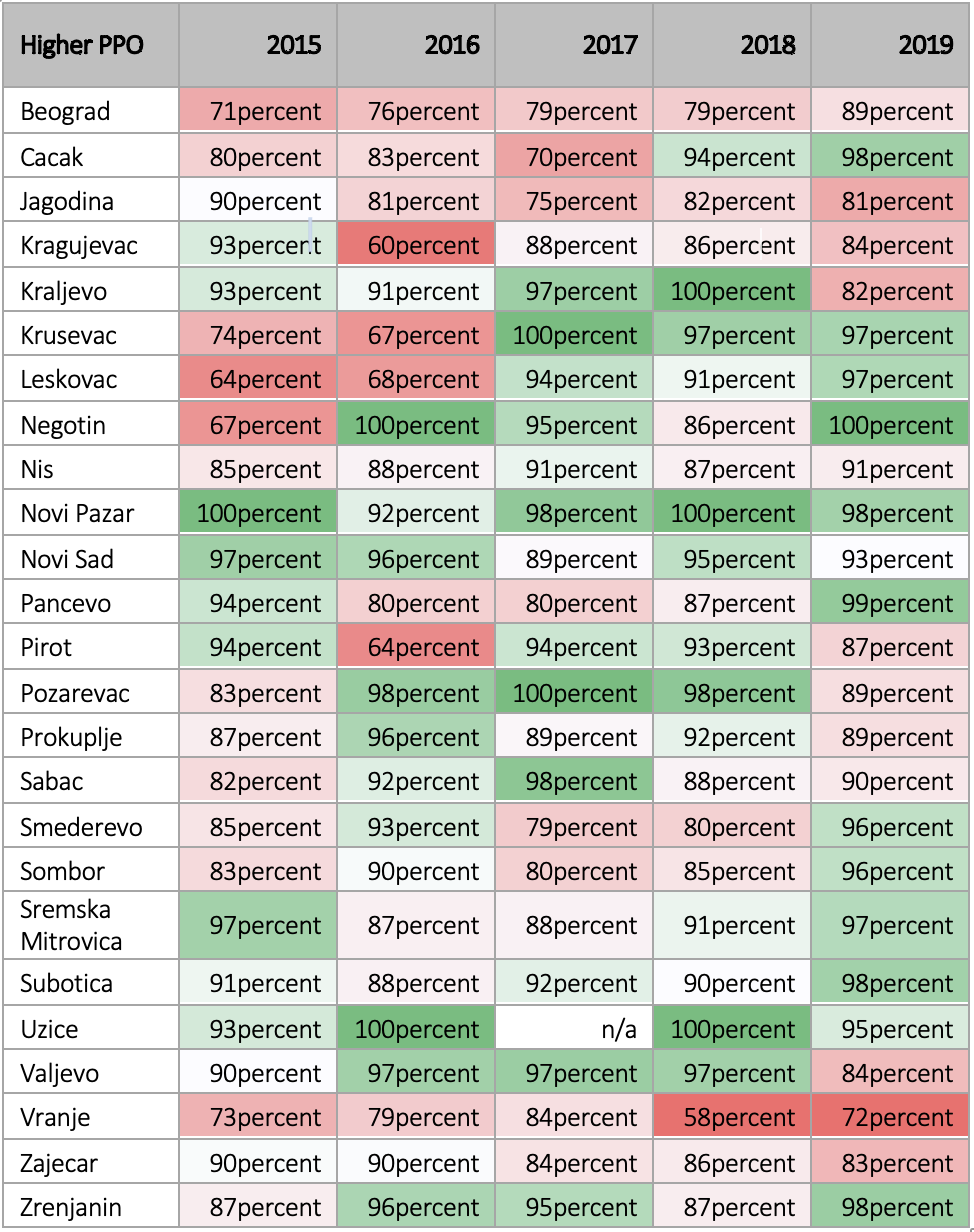

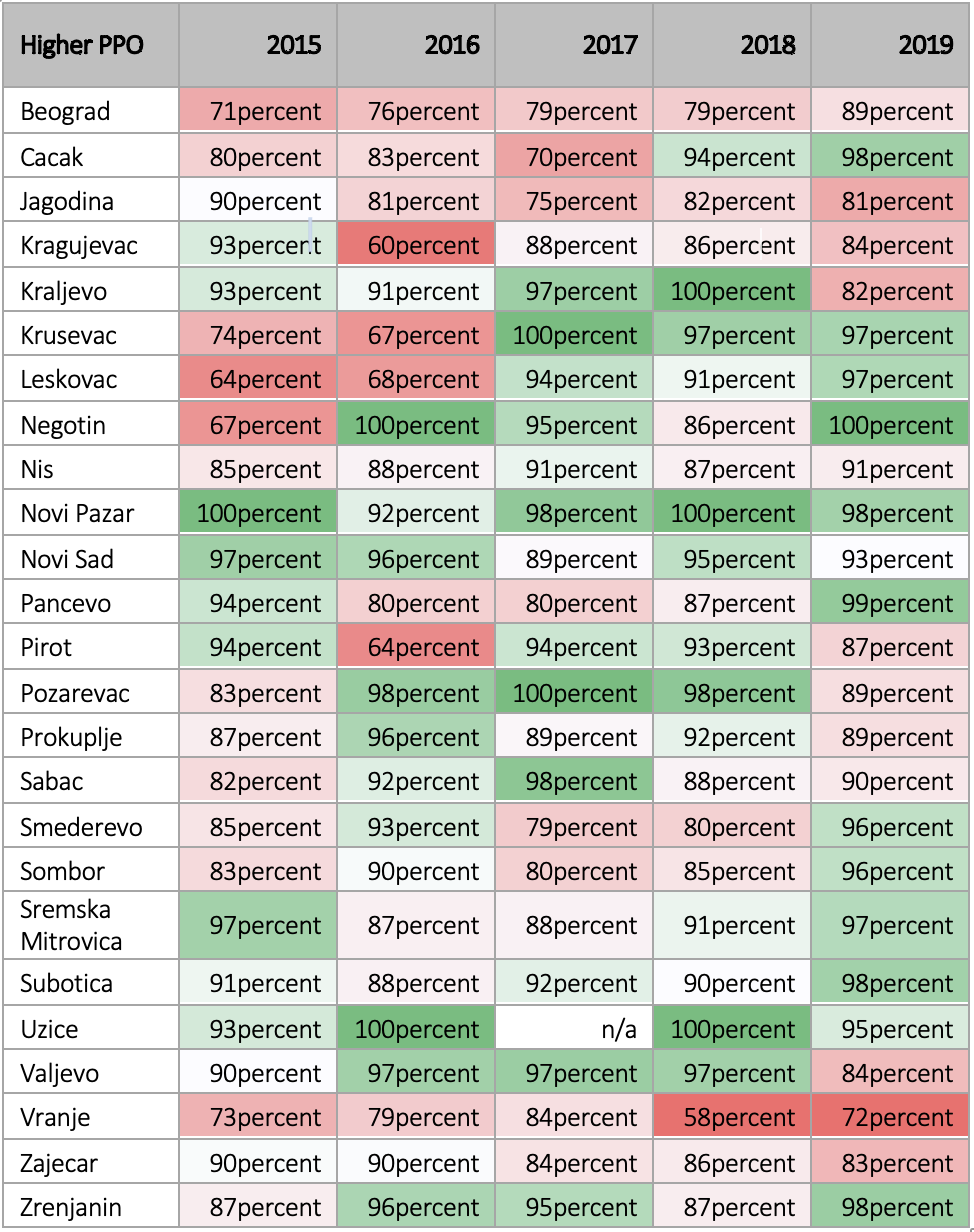

- The conviction rates of Higher PPOs also had similar

variations, but the FR team could not locate any analyses of the

possible causes of the variations. For instance, the conviction

rate for the Higher PPO in Vranje dropped from 84 percent in 2017 to 58

percent in 2018. The rate for the Higher PPO in Belgrade increased each

year by a total of 18 percentage points from 2015 to 2019. The three

Higher PPOs with the lowest rates in 2019 were Vranje (72 percent),

Jagodina (81 percent), and Kraljevo (82 percent). In contrast, the rate

for the Higher PPO in Leskovac rose from 64 to 97 percent in 2019. Only

two Higher PPOs, in Novi Pazar and Uzice, managed to maintain conviction

rates of 90 percent or higher over the five observed years(there was no

data available for Uzice for 2017).

Figure 95: Convictions per Higher PPO from 2015 to 2019

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2015-2019

- Conviction rates of Specialized PPOs and specialized

departments in select Higher PPOs also varied significantly.

The Special Prosecutor’s Office for Organized Crime reported conviction

rates from 75 to 91 percent from 2015 to 2019

while conviction rates of the Special Prosecutor’s Office for War Crimes

ranged from zero to 83 percent. Conviction rates for

the Special Prosecution Office for High Tech Crime within the Belgrade

Higher PPO improved from 37 percent in 2015 to 91 percent in 2019. The specialized departments to

combat corruption, established in 2018 in four Higher PPOs, produced a

100 percent conviction rate that year and a rate of 96 percent in

2019.

Quality in Decision-Making ↩︎

Control

Mechanisms and Coordination in Case Processing ↩︎

- There were no changes to the highly hierarchical

structure of Serbia’s prosecutorial system between the publication of

the Prosecutorial FR and the end of 2019. Higher-instance

Public Prosecutors still had the right to control the work of

lower-instance ones; the higher-instance prosecutors could take over any

matters of lower-instance Public Prosecutors within his or her

jurisdiction and issue mandatory instructions to those lower-instance

Public Prosecutors.

- By the end of 2019, there still were no effective means

prosecutors could use to force police to follow their

instructions.. Prosecutors interviewed for the FR reported it

still was common for police to ignore or to vary from prosecutorial

instructions about steps to be taken during the investigations.

Prosecutors reported this problem arose particularly in cases that might

have political implications because of political issues or the political

roles of persons involved in a case, which also was true when the

Prosecutorial FR was published in 2018.

- To ensure better quality and control of prosecutors’

work, starting in 2013, the CPC has allowed the filing of complaints

about the dismissal, suspension, or abolition of a criminal complaint,

and Serbians have made extensive use of this process. An alleged victim or the person

who submitted a criminal complaint may request that a higher-instance

PPO reconsider a dismissal.

- The complaints mechanism was applied in eight percent of

the dismissals in Basic PPOs (4,749 complaints) and 43 percent in the

Higher PPOs (2,122 complaints) in 2019. In the absence of any

data to explain the difference of 35 percentage points, the FR team

presumes persons affected by the more serious crimes handled by Higher

PPOs were more apt to feel they had significant interests in the outcome

of those cases.

- In 2019, 12 percent of the 4,749 complaints against Basic

PPO dismissals were adopted by the Higher PPOs while 75

percent were rejected, and 12 percent were carried over to

2020. Since the time limits for this type of complaint against

any dismissal are quite strict, presumably, the carried-over cases were

those received at the end of the year.

- In 2019, eight percent of the 2,122 complaints against

Higher PPO dismissals or 166 were adopted by the applicable Appellate

PPOs, while 1,739 were rejected, and 217 were carried

over.

- In both Basic and Higher PPOs, the figures related to

injured person complaints varied to some extent from 2014 through 2019

but without a distinct pattern. Approximately 3,500 to 4,500

complaints were submitted against Basic PPOs dismissals, and 1,000 to

2,500 against Higher PPOs dismissals. Roughly 75 to 85 percent of

complaints against both Higher and Basic PPOs were not accepted, with

the exception of 2017, when 93 percent of the complaints submitted

against Higher PPOs were rejected.

Dismissals ↩︎

- Due to the continuing lack of detail collected about the

reasons for dismissals, the system was still missing a significant

amount of critical data about the quality of this process.

Dismissals in the RRPO’s Annual Reports were broken down into only five

categories, namely ‘insignificant offenses’,

cases dismissed for lack of evidence, deferred prosecutions, unfinished

deferred prosecutions and “other”. It was not even possible to

determine, for instance, how many of the “other” cases had to be

dismissed against adult defendants because the applicable statute of

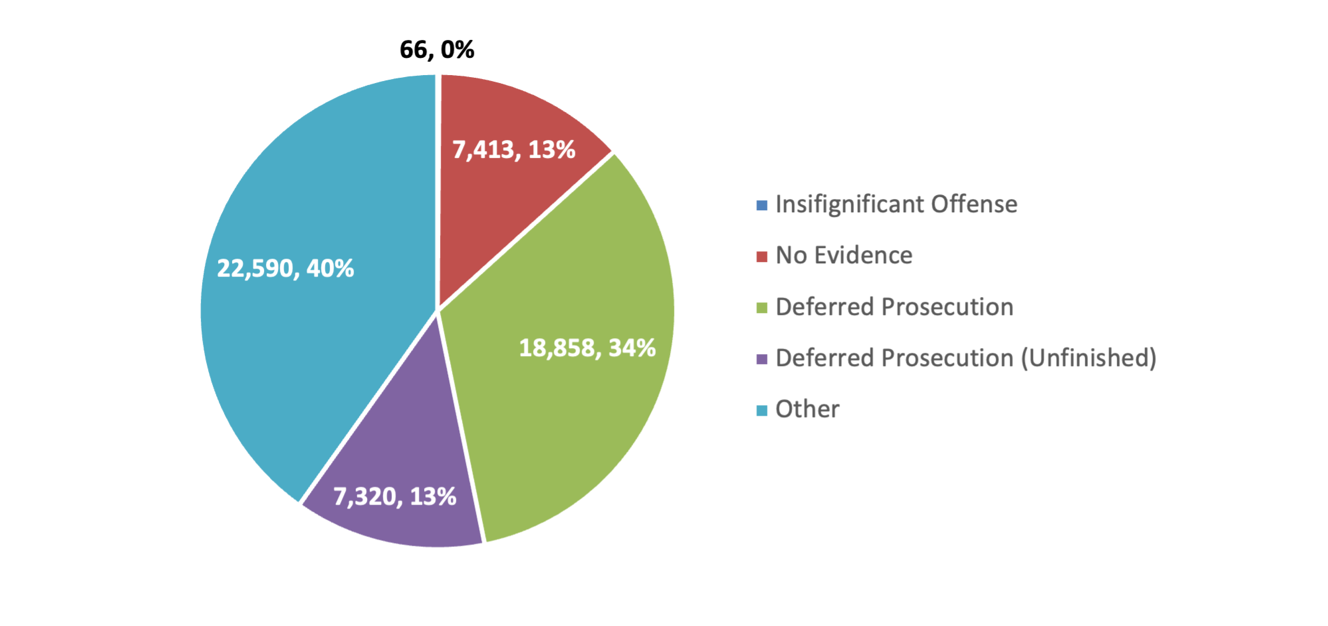

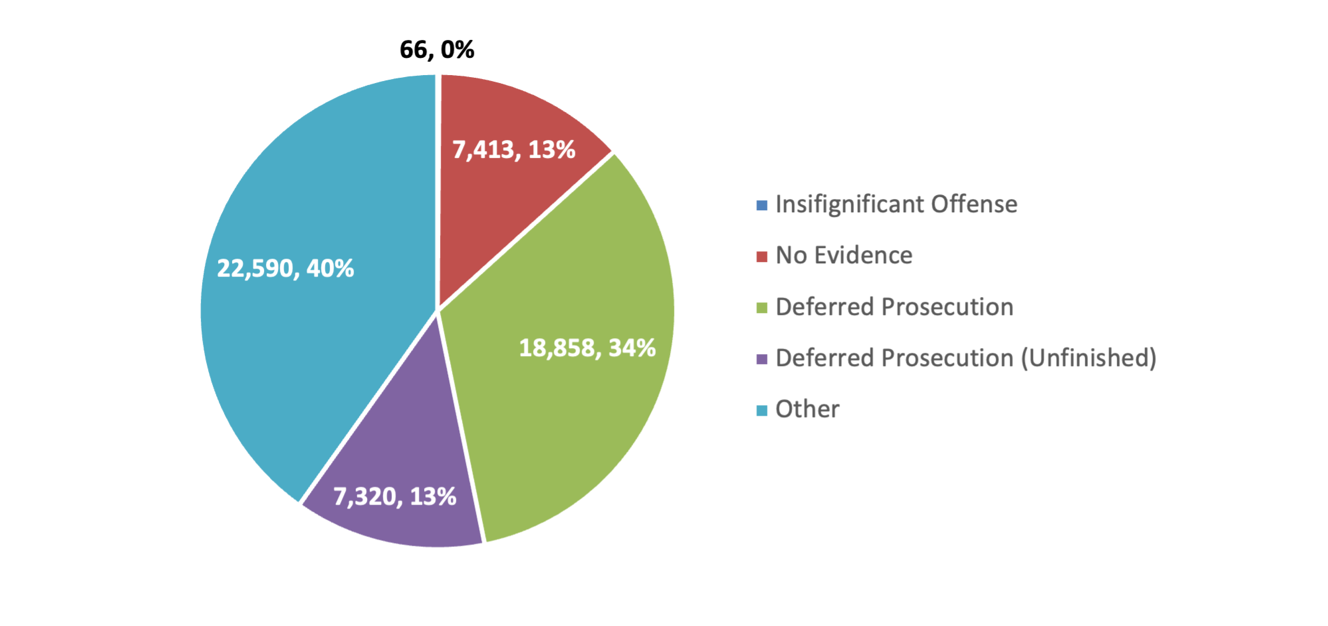

limitations had expired. In 2019, 40 percent of the dismissals of

criminal complaints against adult defendants were handled by Basic PPO,

as shown by, and Figure 96, 87 percent of the same set of cases handled

by Higher PPOs fell in the “other” category.

Figure 96: Dismissals in Basic PPOs by Type in 2019

Source: RPPO Annual Report 2019

- From 2014 to 2019, Basic PPOs dismissed a higher share of

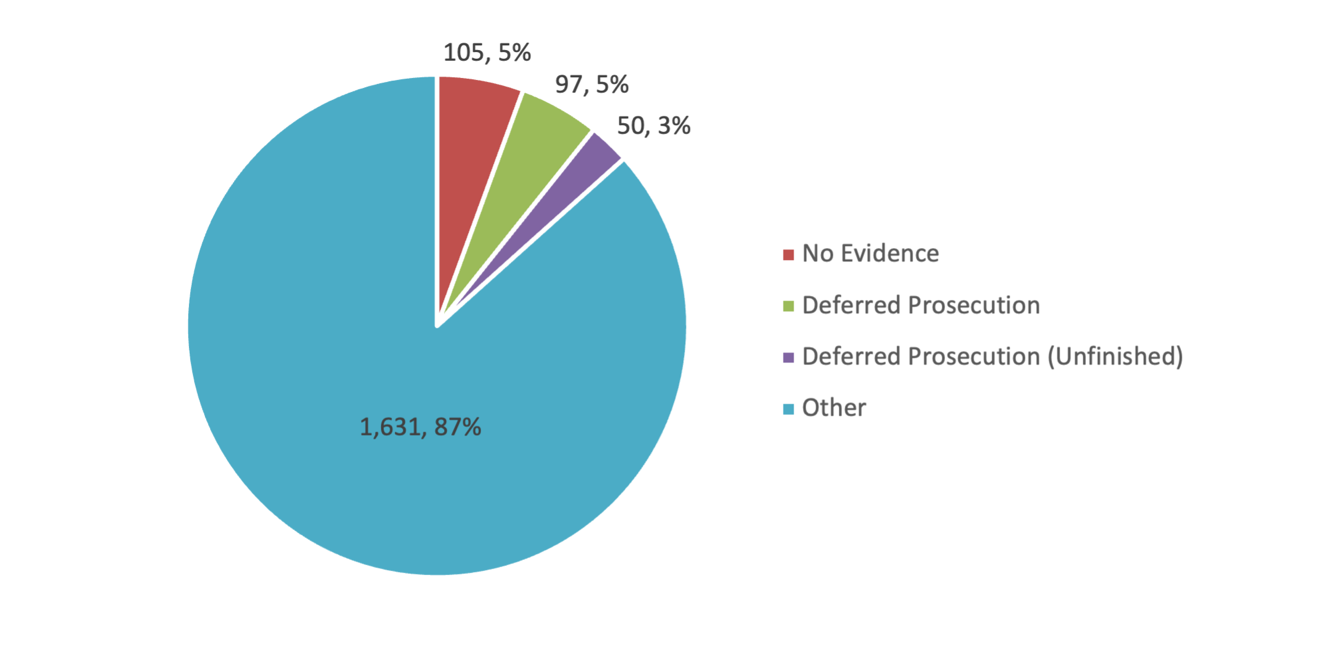

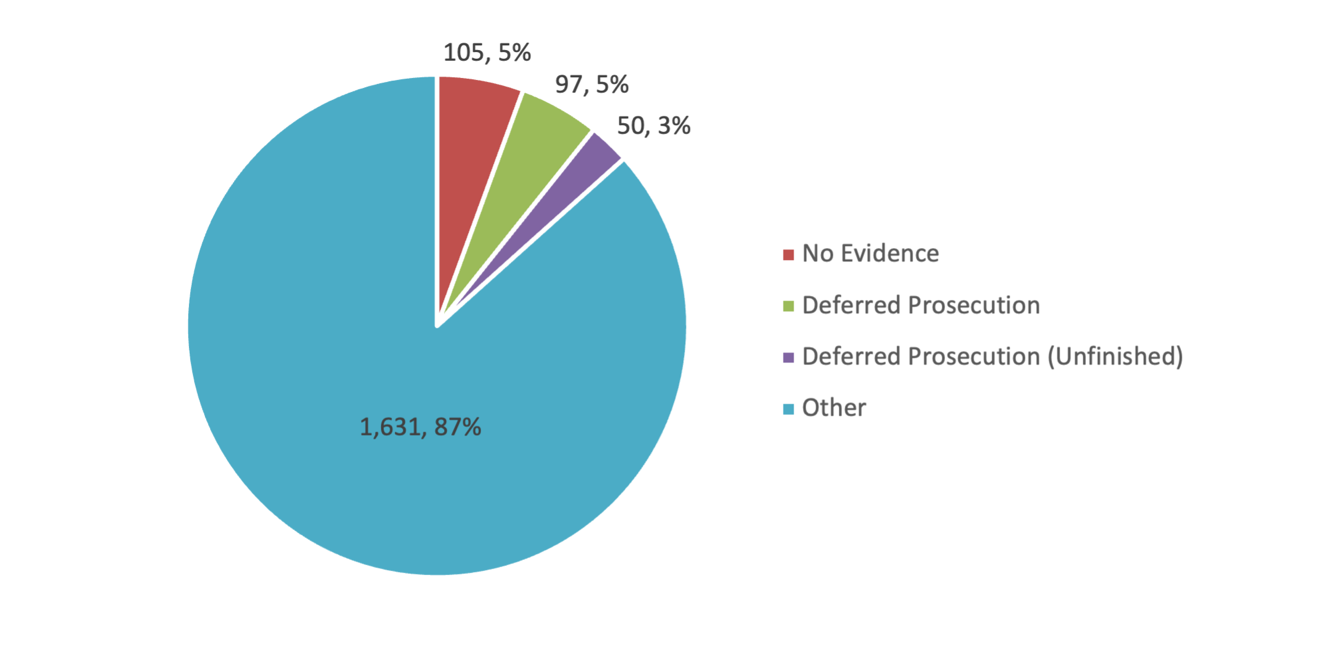

cases than Higher PPOs due to the number of cases for which there was

insufficient evidence. In 2019, only five percent of dismissals

in Higher PPOs were for lack of evidence, compared to 13 percent of the

dismissals of the same type in Basic PPOs. See Figure

97.

Figure 97: Dismissals in Higher PPOs by Type in 2019 (Adult

Perpetrators)

Source: RPPO Annual Report 2019

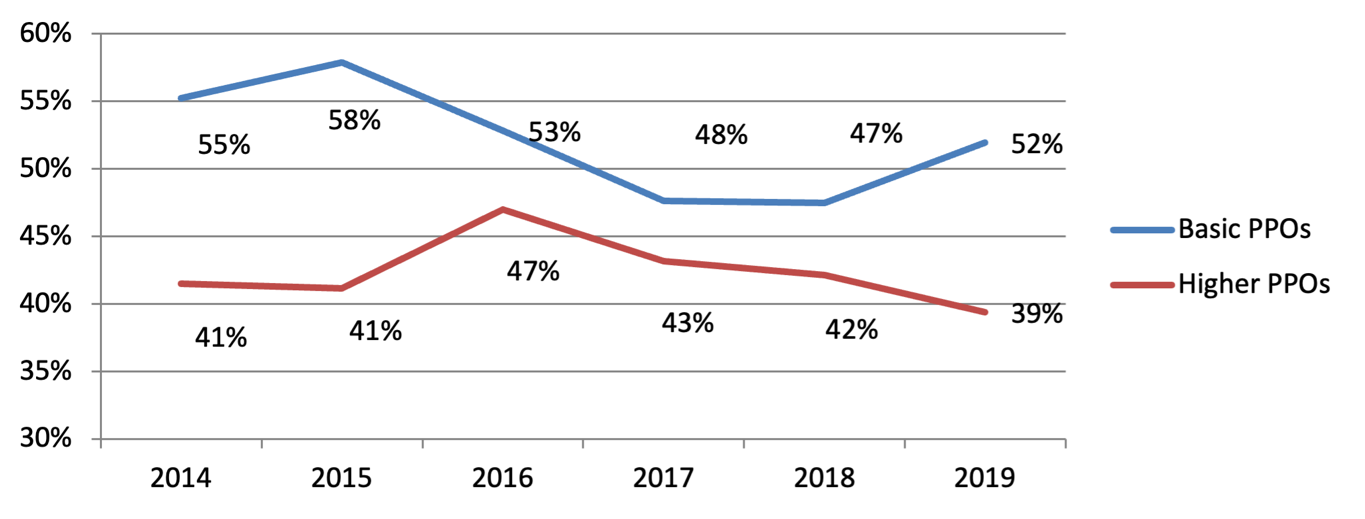

- Comparison of earlier figures to the share of cases shown

as “discontinued” in the CEPEJ 2020 report,

which was based on 2018 data, should be done with

caution. Serbia’s statistics show the share of dismissals in

the number of disposed of cases ranged from 47 to 58 percent of the

cases disposed of for Basic PPOs and 39 to 47 percent for Higher PPOs. The CEPEJ 2020 report found that

Serbian prosecutors discontinued 3.28 cases per 100 inhabitants, which

was higher than the averages for the EU (1.91) and EU11

(1.10), and the Western Balkans (1.33) average.

While these numbers could be read to show a tripling of the cases

discontinued by Serbian prosecutors compared to the previous CEPEJ

report based on 2016 data, between the two reports Serbia changed its

definition of what counted as a case against adult defendants processed

by a public prosecutor. Therefore, the

differences from the earlier numbers probably are not as high as they

appear in the CEPEJ report. See Figure 98.

Figure 98: Percentage of Dismissed Cases in Basic and Higher PPOs

from 2014 to 2019

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014-2019

- Also in 2019, of the dismissals of juvenile justice

complaints handled by Higher PPOs, 44 percent were dismissed because the

defendant was too young to be prosecuted for the crime charged and

deferred prosecution was applied in 23 percent of the

dismissals. The bases for the remaining 33 percent of

dismissals were not specified; for instance, dismissal statistics for

juveniles did not contain separate categories for lack of evidence or

insignificant offenses.

Deferred Prosecution ↩︎

- According to the CEPEJ 2020 report (2018 data), with a

score of 0.27 Serbia reduced the number of cases ‘concluded by a penalty

or a measure imposed or negotiated by the prosecutor’, including

deferred prosecutions, for the second time in a row. As opposed

to the previous two evaluation cycles, when the reported ratio was one

of the highest among covered countries,

the latest figures are more modest and well under the CoE average of

0.45. However, they still were more than double than the EU11 average of

0.10. In the CEPEJ 2016 report (2014 data), Serbia’s reported ratio was

0.53, and in the 2018 report (2016 data) 0.36. Many of these differences

probably were affected by Serbia’s decision to expand its definition of

cases against adult defendants processed by prosecutors between 2016 and

2018.

- Compared to 2018, in 2019 Basic PPOs increased the number

of deferred prosecutions by 6 percent, while the Higher PPOs reduced the

number of deferred prosecutions by 74 percent.

The reasons behind the decline among the Higher PPOs were not

documented; presumably, at least part of the decline was due to concerns

about possible overuse of the procedure, as discussed at page 41 of the

Prosecutorial FR.

- Deferred prosecution was applied in 707 juvenile criminal

cases in Higher PPOs in 2019, which represented 23 percent of the

dismissals of juvenile criminal cases. In preceding years,

deferred prosecution attained a similar share in dismissals of juvenile

criminal complaints. There were 619 deferred prosecutions (22 percent)

in 2014, 689 (26 percent) in 2015, 875 (28 percent) in 2016, 834 (24

percent) in 2017, and 468 (14 percent) in 2018.

- Some deferred prosecutions were classified as

‘unfinished’ because the defendant still had time to meet his or her

obligations. Although there still were no statistics available

by the end of 2019 for the number of cases in which the deferred

prosecution was revoked because the conditions of deferral had not been

met, the Prosecutorial FR estimated defendants had failed to comply with

the terms of the deferred prosecution in up to 10 percent of the

deferred prosecution cases.

Table 15: Deferred Prosecution per PPO Type from 2014 to 2019 (Adult

Perpetrators)

| Basic PPOs |

Deferred Prosecution |

17,447 |

21,074 |

20,083 |

16,706 |

17,802 |

18,858 |

| Deferred Prosecution (Unfinished) |

15,706 |

14,216 |

9,011 |

8,787 |

7,874 |

7,320 |