Main Findings ↩︎

- Despite numerous anti-corruption initiatives and some

improvements in normative and institutional frameworks, prevention of

judicial corruption and impunity remained an issue of concern in Serbia

from 2014 to 2022. There still was no effective coordination

mechanism in place for the prevention, reduction or elimination of

corruption. In October 2020, the Group of States against Corruption

(GRECO) found that since 2015, Serbia had satisfactorily implemented

only two of GRECO’s 13 recommendations regarding “Corruption prevention

in respect of members of parliament, judges and prosecutors,” which led to GRECO’s evaluation of

the situation as “globally unsatisfactory”.

However, in March 2022, in the Second Interim Compliance report, GRECO concluded that the overall

level of compliance with the recommendations was no longer “globally

unsatisfactory” as ten recommendations had been partially

implemented.

- Judicial institutions have not made use of integrity

plans. Such plans are required by the Law on the Prevention of

Corruption as a means of self-assessment, but there is no evidence that

they have been used effectively to develop or strengthen safeguards

against corruption.

- There are still notable openings for the exercise of

undue influence on the judicial system. The constitutional and

legislative framework continued to leave room for undue political

influence over the judiciary, and pressure on the judiciary remained

high. The 2022 Constitution amendments

remove the role of the executive and legislative branches from the

process of appointment of judges and composition of the HJC. However,

for the operationalization of the new provisions, the legal framework

has to be adopted and it is set for March 2023. Government officials,

some at the highest level, as well as members of Parliament, continued

to comment publicly on ongoing investigations and court proceedings and

about individual judges and prosecutors, while articles in tabloid

newspapers targeted and sought to discredit members of the judiciary.

- The SPC established the Commissioner for Autonomy in 2017

to report to the public on claims of undue influence or attempts to

place undue influence on prosecutors. However, the post was not

filled from March 2020, when the term of the first Commissioner expired,

through the end of the mandate of the SPC composition in March 2021. The

new Commissioner was appointed in April 2022, but the rules of procedure

for the Commissioner and needed resources are still missing.

- The automated, random assignment of cases became the

official norm in Serbia’s courts by 2018, but the Law on Judges and the

Court Rules of Procedure still contained fairly broad provisions that

allowed court presidents to assign or transfer a case to a particular

judge, despite the general prohibition of deviating from random

assignment. There was no centralized tracking of cases that

were not randomly assigned. There still was no automated mechanism for

the random assignment of cases in PPOs.

- There was no central tracking of the source, basis, or

disposition of written complaints about court and prosecutorial

operations. Complaints were submitted directly to courts and

PPOs and/or the SCC, RPPO, the Councils, the Ministry of Justice, and

the Anti-corruption Agency (ACA) / Agency for Prevention of Corruption

(APC). Each court was obligated to collect and submit complaint

statistics every six months to the MOJ, SCC, HJC, and its immediately

superior court. The Ministry of Justice introduced

an automated system for complaints, however, it is not linked with other

stakeholders. However, there was no office in

the system with unified numbers for the written complaints received

during the period under review, how many complaints were submitted to

more than one institution, how many were ignored, and how many were

considered to be valid.

- From 2017 to 2022, Serbia made significant steps in

integrating ethical codes for judges and prosecutors into the regimes

governing their behavior. Ethical boards were established as

permanent bodies within the HJC and SPC, while ”Ethics and Integrity in

the Judiciary” were one of the most frequently covered thematic areas

within the JA’s continuous training curricula on “Special Knowledge and

Skills.” Furthermore, continuous training curricula for holders of

judicial office shifted to include more skills-based training on ethics

and integrity.

- The appointment of expert witnesses does not conform to

international standards for impartiality, leaving the Serbian judicial

system vulnerable to corruption. There were no clear and

transparent rules about the process that prosecutors use to appoint

expert witnesses in criminal proceedings. Experts in the same field were

not always paid at the same rates. These variations reportedly

influenced the selection of witnesses by parties or judges and the

quality of their work. The MOJ did not keep systematized data when

revoking the authorization of experts for unethical, incompetent or

unprofessional performance. Experts who missed deadlines or hearings

generally were not penalized.

- While judicial institutions have complied with the Law on

the Protection of Whistleblowers, adopted in 2014 by appointing

whistleblower point persons, these individuals have not received

training in how to carry out their responsibilities. In

addition, surveys indicate that employees of the judicial system are not

well-informed about the protections under this law.

- In large part, the legal frameworks governing the

disciplinary accountability of judges and public prosecutors conformed

to international standards. The major exception was the

continued designation of the Councils as the second-instance

disciplinary bodies, particularly since the Councils also elect members

of the respective Disciplinary Commissions for judges and prosecutors. There is also a need for clarity

in the grounds for discipline.

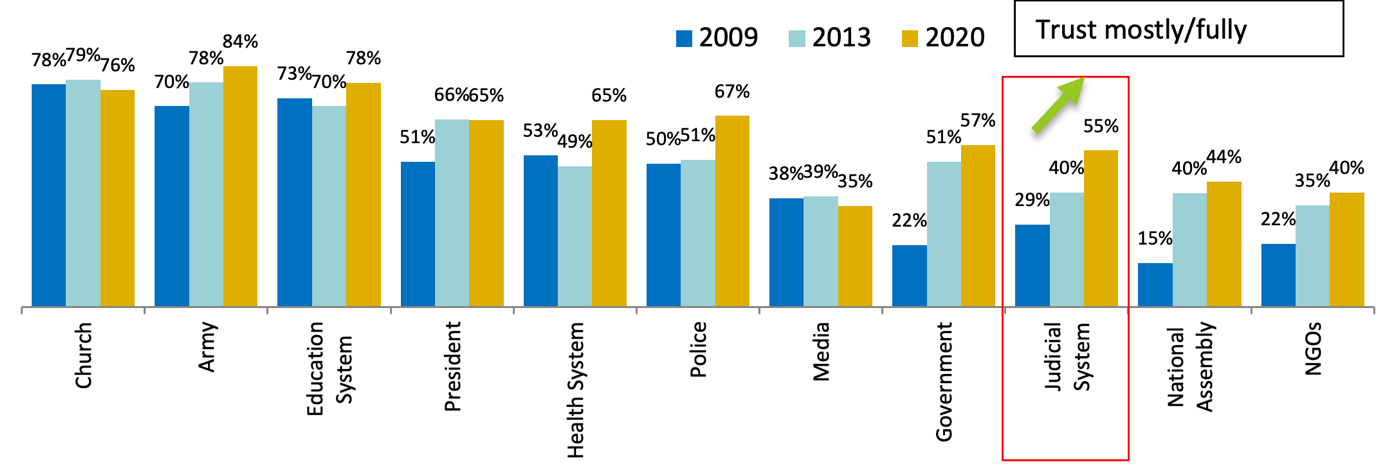

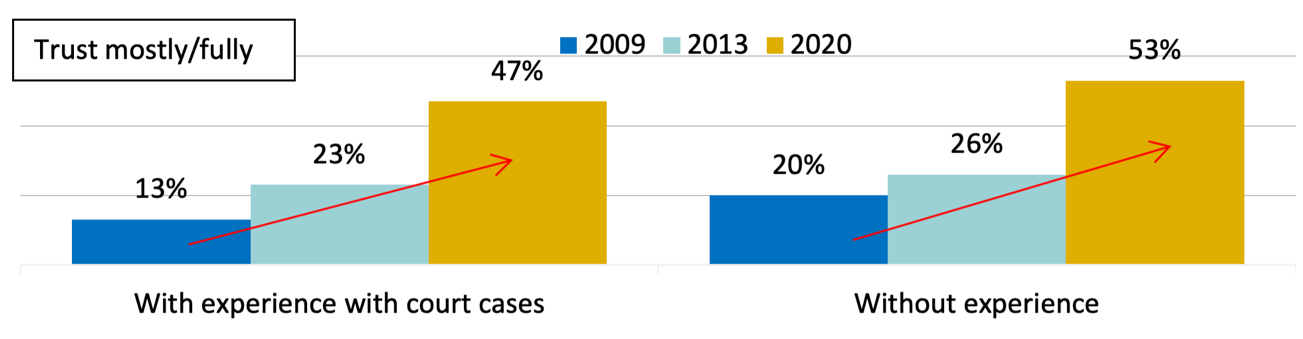

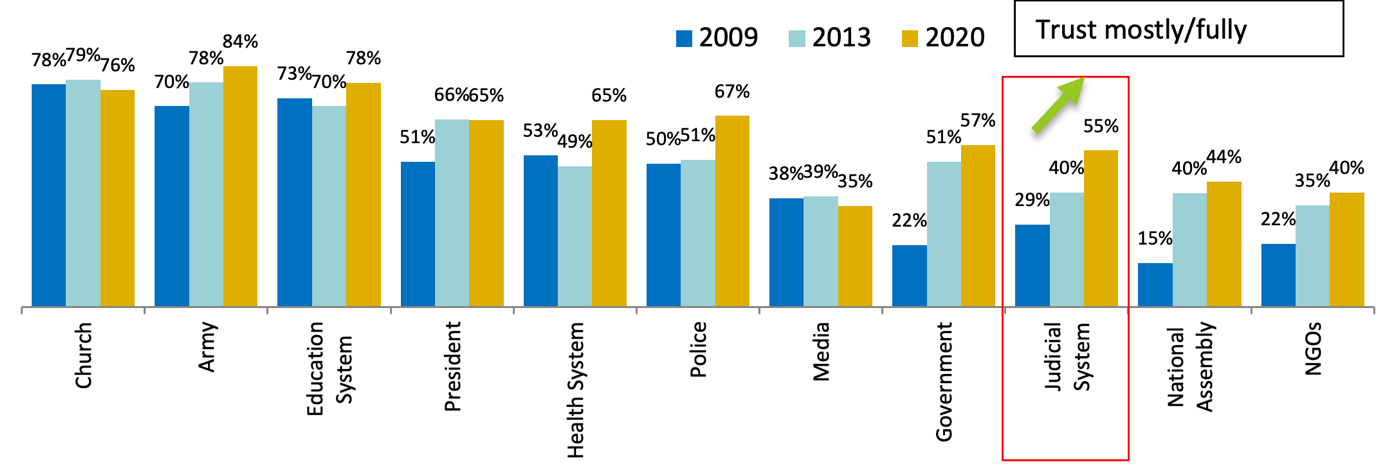

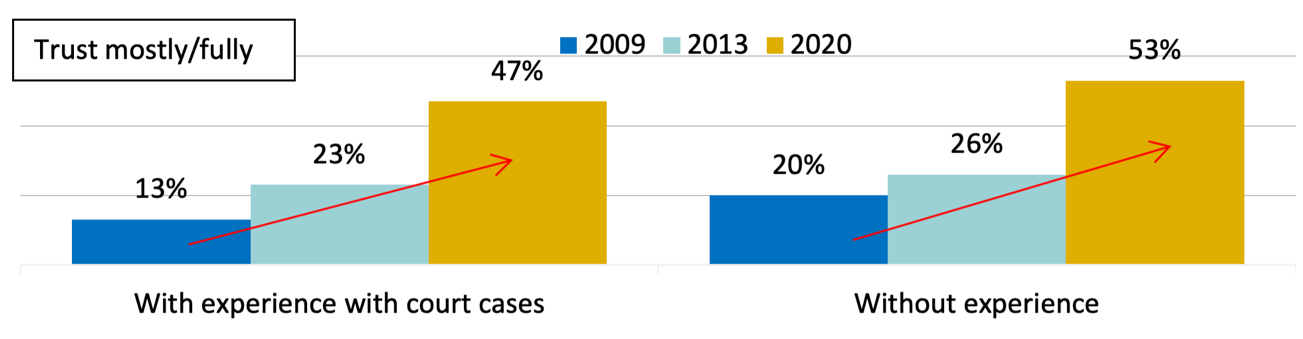

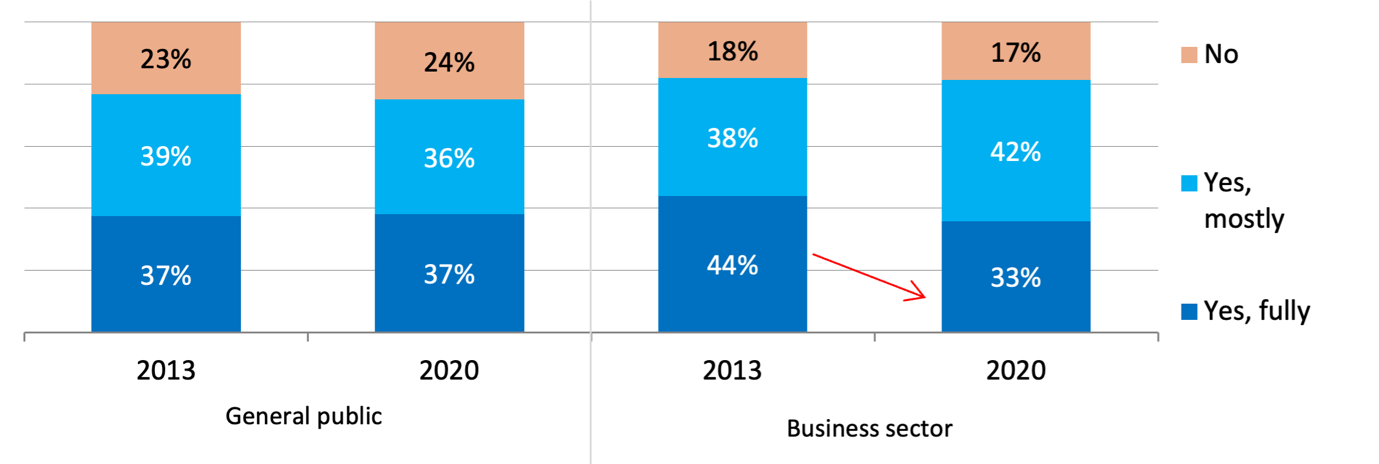

- The 2020 Regional Justice Survey showed a significant

increase in the trust of Serbian citizens in their judicial system,

compared to 2009 and 2013. The judicial system was in the

middle of the 2020 ladder of trust, at 55 percent. This improvement was

part of a pattern of increased trust in state institutions generally,

with the exception of the media. Trust in the judicial system increased

both among court users and the general public.

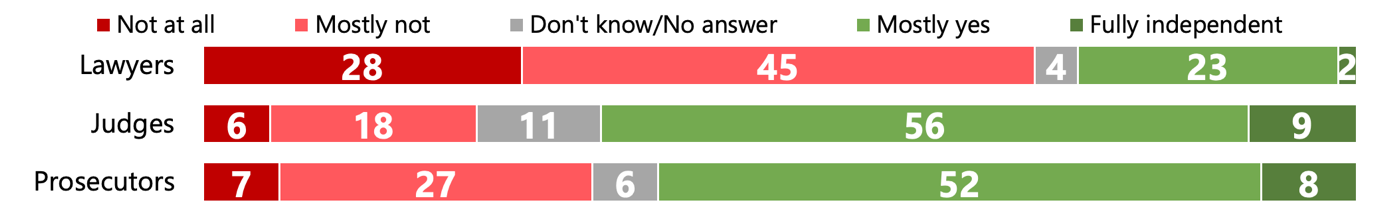

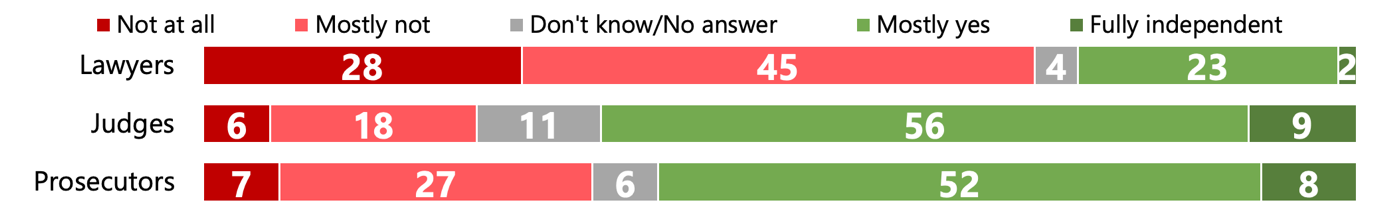

- A significant portion of judges, prosecutors, and lawyers

report that the judicial system is not independent in practice.

Approximately 24 percent of judges and 34 percent of prosecutors

reported that the judicial system is not independent. Lawyers are even

more skeptical, with 73 percent of lawyers reporting that the judicial

system is not independent.

Introduction ↩︎

- Ensuring that judicial functions are conducted with

integrity is of the utmost importance to Serbia’s democratic and

economic future. The EU’s revised Western Balkan enlargement

methodology, adopted by the European Commission in 2020, places an even

stronger focus on the core role of fundamental reforms essential for

Serbia’s EU accession, including judicial reform.

This represents an application of international standards that recognize

no society can be considered serious about fighting corruption if its

judiciary or security services are perceived to be operating with

impunity. Maintaining a culture of integrity cannot be accomplished by

repressive measures alone: promoting integrity requires safeguarding the

independence and autonomy of judges and prosecutors and eliminating

aspects of the system that create opportunities for corruption to

flourish.

- For purposes of this review, both ‘integrity’ and

‘corruption’ are used in a broad sense. ‘Integrity’ encompasses

the ability of the judicial system or an individual judicial actor to

resist corruption while fully respecting the core values of judicial and

prosecutorial independence, impartiality, personal integrity, propriety,

equality, competence, and diligence.

‘Corruption’ includes bribery or intimidation of judges, court staff, or

public prosecutors, abuse of official authority by holders of judicial

office, influence peddling, and exercising undue influence on holders of

judicial office (externally by political actors, media, etc., or

internally by colleagues or higher-ranking officials within the

system).

- In 2019, Serbia adopted a Law on Prevention of

Corruption, which replaced and

expanded upon the Law on the Anti-Corruption Agency adopted in

2008. The objectives of the 2019 Law, which took effect in

September 2020, are the protection of the public interest, the reduction

of corruption risks and the strengthening of the integrity and

accountability of public authorities and public officials. (See Box 21).

The 2019 Law changed the name of the Anti-Corruption Agency to the

Agency for the Prevention of Corruption and expanded and clarified the

duties and mandate of this independent state authority.

Box 21:The 2019 Law on Prevention of Corruption

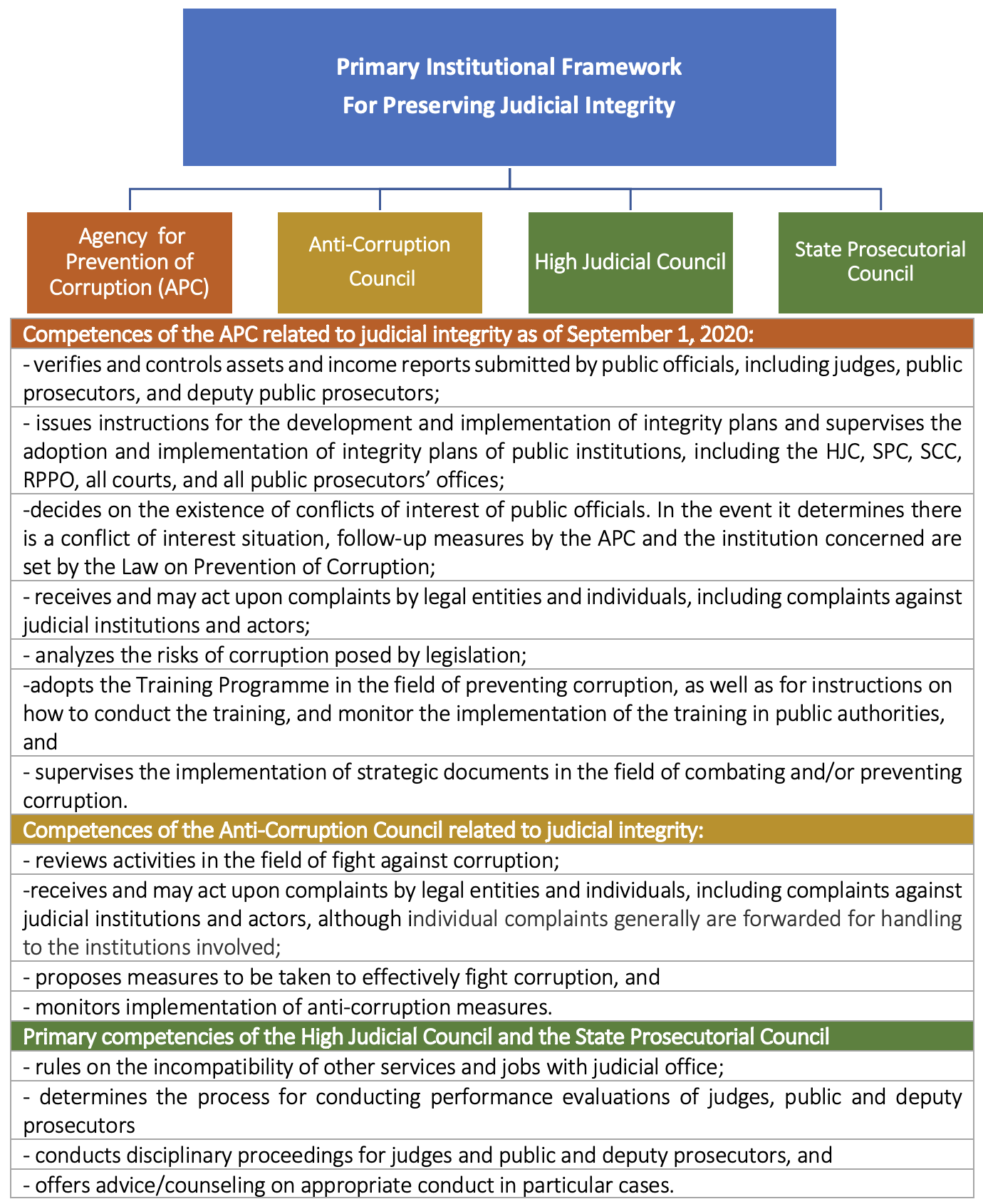

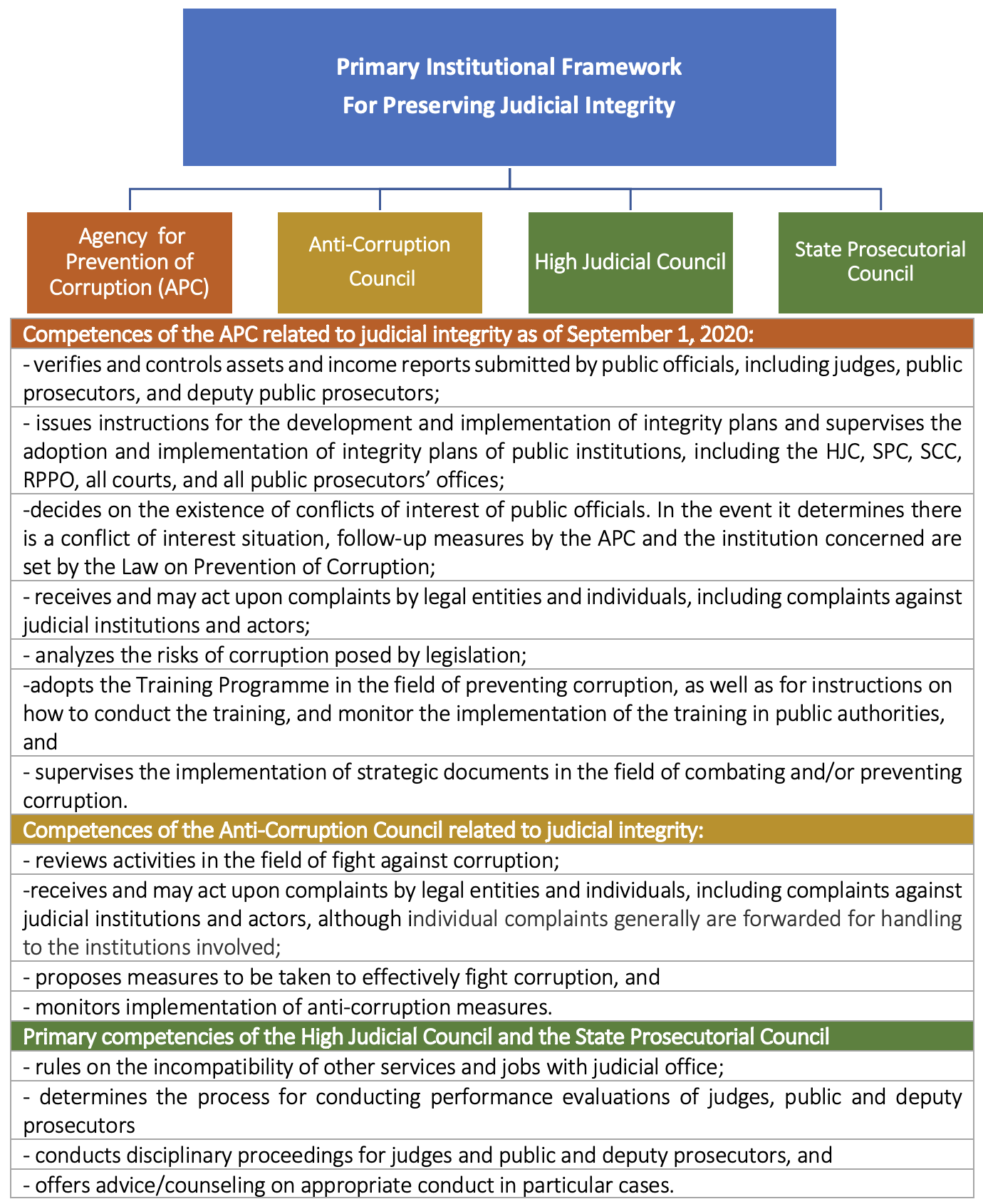

- In addition to those shown in Figure 114 below,

institutions and organizations with roles to play in preventing and

reporting corruption include the Ministry of Justice, the National

Assembly, the Judicial Academy, and civil society

organizations. Persons working within the judicial system with

anti-corruption roles include individual judges, prosecutors, judicial

and prosecutorial staff, lawyers, and expert witnesses.

Figure 114: Institutional Framework for Integrity in the Judicial

Sector

- Few of the recommendations related to the problem of

corruption in the judiciary from the 2014 Functional Review had been

fully implemented by the end of 2020. The 2014 Functional

Review contained six recommendations, consisting of 20 sub-parts,

related to issues of corruption in the judiciary. Of the 20, only two

were completely implemented, seven were partially implemented, and 11

were not implemented at all.

- Despite numerous anti-corruption initiatives and some

improvements in normative and institutional frameworks, prevention of

judicial corruption and impunity remained an issue of concern in Serbia

from 2014 to 2020. There still was no effective coordination

mechanism in place for the prevention of and reduction or elimination of

corruption. In October 2020, the Group of States against Corruption

(GRECO) found that since 2015, Serbia had satisfactorily implemented

only two of GRECO’s 13 recommendations regarding “Corruption prevention

in respect of members of parliament, judges and prosecutors,” which led to GRECO’s evaluation of

the situation as ‘globally unsatisfactory’.

- There are still notable openings for the exercise of

undue influence on the judicial system. The constitutional and

legislative framework continued to leave room for undue political

influence over the judiciary, and pressure on the judiciary remained

high. Government officials, some at the

highest level, as well as members of parliament, continued to comment

publicly on ongoing investigations and court proceedings and about

individual judges and prosecutors, while articles in tabloid newspapers

targeted and sought to discredit members of the judiciary.

- The most fundamental change to the promotion of integrity

is the 2022 Constitutional amendments that reduce openings for political

influence on judicial operations affecting the membership and duties of

the HJC and SPC. However, for the

operationalization of the new provisions, the legal framework has to be

adopted, and it is set for March 2023. These changes are discussed in

the Governance and Management chapter.

Institutional Coordination ↩︎

- There was insufficient cooperation and coordination among

the institutions with responsibility for building the integrity of

Serbia’s judiciary for the country to improve its reputation related to

corruption in the judicial system. This is a message the

institutions and their leaders have heard many times, e.g., from the

annual Communications on EU Enlargement Policy as well as the 2014

Judicial Functional Review.

The lack of coordination included the lack of sufficient interaction

between the Councils and the Anti-Corruption Agency/APC about the

development, implementation, and monitoring of integrity plans, rules,

and standards governing conflicts of interest and implementation of

those rules and standards.

- The Councils’ lack of centralized databases that collect

all written complaints about the work of judicial institutions impaired

the system’s ability to track breaches of integrity provisions by

judicial officials or employees and to correct problems in justice

service delivery. While there was no legislation requiring the

Councils to collect and analyze all written complaints about the system,

the failure to collect and analyze complaints posed significant

integrity (as well as governance and quality) issues for the judicial

system. The Councils were unable to determine how many

of the complaints were duplicates or how many pertained to a particular

type of case or to a particular court, PPO, judge, prosecutor, or

employee. Given their responsibilities for system performance and the

selection, training, evaluation, ethics, and discipline of judges and

prosecutors, the Councils were in the best position to collect and

analyze the data related to judicial integrity in coordination and

cooperation with other competent institutions.

- The judicial system failed to inform the outside

institutions that originally received complaints about judicial

corruption and/or justice service delivery. This represented

another gap in Serbia’s ability to track and correct breaches of

integrity provisions by judicial officials. Through 2020, these

complaints were made to the court presidents and public prosecutors of

PPOs, the Councils, the SCC, RPPO, APC, and the Ministry of Justice.

Until the Law on Prevention of Corruption took effect, there was no law

requiring any judicial institution to report back to a non-judicial

agency receiving the complaint about its disposition,

except to the Ministry of Justice in line with the Law on Court

Organization. For example, the APC reported to

the World Bank team that relevant judicial institutions did not

routinely tell the Anti-Corruption Agency about the outcome of the 117

complaints about corruption in the courts or PPOs from 2015 to 2020. In

that period, the Anti-Corruption Agency received a total

of 283 complaints related to the work of courts and public prosecutor's

offices. Of that number, 96 complaints were related to the suspicion of

corruption in courts, criminal offenses against official duty, and

criminal offenses against the judiciary by judges. Also, 21 complaints

were related to the suspicion of corruption in PPOs and criminal

offenses against official duty and criminal offenses against the

judiciary by public prosecutors and deputy public prosecutors.

Table 17: Structure of complaints to the APC related to the work of

courts in the period 2015-2020

Table 18: Structure of complaints to the APC related to the work of

PPOs in the period 2015-2020

- The Law on Prevention of Corruption requires judicial

institutions to inform the APC about the outcome of complaints forwarded

by that agency only when the APC determines “there are circumstances in

the work of a public authority that might lead to

corruption.” In those cases, the APC must

recommend measures for the public authority to remedy the situation,

along with a time limit for taking the measures, and the receiving

institutions are obliged to inform the APC about the outcome of those

measures.

Development and

Monitoring of Integrity Plans ↩︎

- Integrity plans are designed to be self-assessments of an

institution’s exposure to opportunities for corruption and other

irregularities, but there was no evidence the judicial system used them

effectively to develop or strengthen its safeguards against

corruption. From 2012 to 2015, public institutions developed

and implemented their initial integrity plans and completed the first

cycle of implementation. The second cycle started in December 2016 and

lasted until October 2019. In preparation for the second cycle, the

Anti-Corruption Agency worked with the MoJ and the Councils to develop

model integrity plans for judicial institutions. Each institution could

add risk areas and processes beyond those in the model plans, but none

of the judicial institutions chose to do so.

For instance, no court or PPO identified risks related to the

implementation of rules on deferring criminal prosecution, concluding

plea agreements or the recusal of judges or public prosecutors, although

these were issues discussed throughout the criminal justice system from

2012 through 2019.

Table 19: Areas Identified in the Integrity Plans of judicial

institutions

as Most Vulnerable to Corruption

- Ethics and Personal Integrity

- Security

- Institutional Management

- Human Resources Management

- Documentation Management

- Public Procurement

- Financial Management |

- IT Security - Security of information

- Human Resources Management |

Source: Data from the Anti-Corruption Agency, July 2019

- Effective use of the plans also was hampered by the

failure of judicial institutions to appoint senior personnel to develop

and monitor the implementation of integrity plans and the lack of

transparency about their contents. APC data shows integrity

plans were adopted by 84percent of judicial institutions in the first

cycle and 88 percent in the second. However, as of the

end of 2020, most judicial institutions, including the MoJ, the

Councils, courts, and PPOs, also had failed to follow the

Anti-Corruption Agency recommendations that integrity plans be posted on

each institution’s web page.

Rules

on conflict of interest, undue influence, and declarations of

assets ↩︎

- From 2015 to 2020, under the Law on the

Anti-Corruption Agency/Law on Prevention of Corruption, the

Anti-Corruption Agency initiated 217 proceedings against judges and

public prosecutors for violations of statutory provisions related to

assets and income disclosures, conflicts of interest of public

officials, and the statutory rules on gift-giving. Of these,

196 proceedings were completed. These resulted in 185 measures of

caution, seven public announcements that violations had occurred, and

four proceedings were suspended. Measures of caution

were the mildest available sanctions for these violations.

- The Law on the Prevention of Corruption generally

strengthened and clarified the rules on conflicts of interest and asset

declarations. The judicial and prosecutorial codes of ethics in

effect through 2020 did not address “conflicts of interest” as such, but

the codes and Articles 30-31 of the Law on

Judges and Articles 65-68 of the Law on Public Prosecution did contain

clear prohibitions on external activities that might compromise

impartiality, and the duty to notify superiors of activities that might

do so.

- In April 2021, the HJC and SPC amended their Rules of

Procedure. The HJC adopted amendments to its Rules of Procedure

regulating the prevention of undue influence on individual judges and

the judiciary as a whole. Also, the SPC

decided to revise the Rules of Procedure with improved provisions

regulating the prevention of undue influence on prosecutors. Those Rules

now provide the basis for the functioning of the Commissioner for

Autonomy of the Prosecution. Following the amendments of its Rules of

Procedure, the HJC conducted numerous activities to promote reporting of

undue influence on judges and to adequately implement this

mechanism.

- The Code of Ethics for Public Prosecutors and Deputy

Public Prosecutors and accompanying guidelines adopted by the SPC in

April 2021 contains a series of principles related to conflicts of

interest. However, conflict of interest is

not presented as a separate topic, and different types of conflict of

interest are not elaborated on in the new Code. In addition, the Code

recognizes only one strategy for preventing or resolving a conflict of

interest – recusal. The practical effect of this limitation is

aggravated by the lack of any provisions in the Code or guidelines

clarifying when prosecutors should seek a recusal;

Instead, prosecutors are referred back to “the law.”

- By late 2020 there also were efforts to increase

awareness among judges and prosecutors about the problems posed by

potential risks of conflict of interest and undue influence. In addition

to training conducted by the Judicial Academy and discussed in more

detail below, the APC published a Manual for Recognizing and

Managing Conflicts of Interest and Incompatibility of Offices, while Guidelines for the

Prevention of Undue Influence on Judges

and the Guidelines for the prevention of Undue Influence on

Prosecutors were published in February 2019.

Although the Manual was not written only for judges and prosecutors, the

APC promoted it among representatives of the judicial system. Both Guidelines contained

instructions for proper management of these risks.

- Also positive was the 2017 establishment of the

Commissioner for Autonomy by the SPC

in 2017, to report to the public on claims of undue influence or

attempts to place undue influence on prosecutors. The

Commissioner was introduced after the EU 2016 Serbia Report noted that

external pressure was being exerted on the judiciary through many public

comments made about investigations and ongoing cases, including comments

from the highest political levels, and the HJC and SPC had not taken

adequate measures to protect those in the system from the effects of

those comments. As GRECO noted, the Commissioner addressed 18 cases in

2019 and 40 in 2017 and 2018, “he recommended to the SPC to further

protect prosecutors against excessive criticism from the political

sphere, carried out direct inspections to verify in eight cases that the

prosecutors had not worked under undue political influence, published on

its website specific reports and statements on undue influence exercised

on public prosecutors on specific cases.”

- However, the Commissioner’s post was vacant for a year

after the three-year term of the first Commissioner expired in March

2020. With the new composition of the SPC, the new Commissioner

was appointed in April 2021. The SPC also failed to adopt rules of

procedure for the Commissioner as a proper legislative framework for the

operations, as well as necessary resources for the effective work.

Rules on Gifts ↩︎

- Both the Law on Judges and Law on Public Prosecution

Service envisage that acceptance of gifts is contrary to the provisions

regulating conflict of interests and can amount to a disciplinary

offense. The provisions about the receipt of gifts are somewhat

clearer under the Law on Prevention of Corruption than they were in the

Law on the Anti-Corruption Agency. The newer law permits public

officials and their family members to retain only a protocol or

“occasional gift” received in connection with the

discharge of public office, providing the gift’s value does not exceed

10 percent of the average monthly salary without taxes and contributions

in the Republic of Serbia. The gift provisions

of the Law on the Anti-Corruption Agency required officials to

relinquish protocol or “appropriate gifts” with values exceeding five

percent of the value of the average net salary in the Republic of

Serbia.

- There still was concern that the newer law still did not

include criteria to determine whether a gift was "in connection to the

discharge of public office” or not.

Furthermore, the World Bank team could not verify that from 2015-2019

the HJC, SPC, RPPO, individual courts, or PPOs kept the records required

by Article 41 of the Law on the Anti-Corruption Agency of gifts reported

by judicial officials.

Random assignment of cases ↩︎

- The automated, random assignment of cases became the

official norm in Serbia’s courts by 2018, but as of December 2020, there

was no centralized tracking of cases that were not randomly

assigned. Also, as of December 2020, the Law on Judges and the

Court Rules of Procedure still contained fairly broad provisions that

allowed court presidents to assign or transfer a case to a particular

judge, despite the general prohibition on deviating from random

assignment. The combination of Articles 24-27 Law on Judges and the

Court Rules of Procedure allowed non-random assignment if the assigned

judge already was overloaded or the judge had been precluded, in the

event of a prolonged absence on the party of the judge, if the efficient

functioning of the court was jeopardized, or if the judge received a

final disciplinary sanction due to a disciplinary offense for

unjustified procrastination, “as well as in the other cases prescribed

by law.”

- There still was no automated mechanism for the random

assignment of cases in PPOs by late 2020, and the random allocation of

assignments was not the rule. As noted in the 2014 Judicial

Functional Review, Public Prosecutors were supposed to assign incoming

cases to the next Deputy Public Prosecutor based on an alphabetical

list, and the assignments were to be recorded in a case assignment

logbook. However, as of December 2020, Public Prosecutors still had

broad discretionary power to reassign cases when they found it was

justified under the Rules of Administration in the Public Prosecutor's

Office.

Appointment of expert witnesses ↩︎

- The regulatory framework governing expert witnesses in

Serbia did not comply with European standards.

Since expert witnesses are a key component of a well-functioning

court system as they provide evidence that is often decisive in shaping

court decisions, it is vital that expert evidence is seen to be

independent, objective, and unbiased.

- The appointment of expert witnesses has been recognized

as one of the main corruption vulnerabilities in the Serbian judicial

system. Through December 2020,

first-instance courts informed the MoJ about their general needs for

expert witnesses with specific expertise.

However, the MoJ was not bound by the Courts’ requests when it published

its calls for expert witnesses, so the available supply of experts did

not necessarily match the needs of the system. Prosecutors could appoint

expert witnesses in criminal proceedings, but there were no clear and

transparent rules about that process.

- Experts in the same field reportedly did not always

charge or were not always paid at the same rate, in violation of the

Rulebook on Reimbursement of Expert Witnesses. These variations

reportedly influenced the selection of witnesses by parties or judges as

well as the quality of work done by expert witnesses.

Experts also reported it was rare for judges to ask the witnesses to

supply a statement of expenses and specification of fees upon completion

of the opinion, even though this is a Rulebook requirement.

- While the Law on Expert Witnesses allowed the MoJ to

revoke its authorization for experts who performed his or her duties in

an unethical, incompetent, or unprofessional manner, the MoJ did not keep

systematized data about any revocations.

There also were few reported instances of parties or courts penalizing

or seeking redress from experts who missed deadlines or even missed

hearings altogether.

Mechanisms for

the protection of whistleblowers ↩︎

- The 2014 Law on the Protection of

Whistleblowers governed the

reporting of irregularities related to the work of all public

institutions, including those in the judicial system. As a

result, holders of judicial office, judicial and prosecutorial

associates and assistants, and other judicial system staff could use the

mechanisms in the Law to report issues related to the work of their

colleagues and/or of judicial institutions.

- There were no reliable statistics indicating what efforts

had been made to make those working in the system aware of the

availability of the whistleblowing mechanism. Interviews

conducted by the FR team indicated that holders of judicial office,

judicial and prosecutorial associates, and assistants, as well as other

judicial staff, were not sufficiently aware of the possible use of the

whistleblowing mechanisms.

- Interviewees reported that most of the persons designated

to receive the information and conduct whistleblower proceedings had no

training on how to execute their responsibilities. However,

judicial institutions did fulfill their obligation to appoint

whistleblower point persons and to adopt general acts on internal

whistleblowing.

Effectiveness

of Complaints, Ethical Codes and Discipline Processes ↩︎

Complaint mechanisms ↩︎

- There was no central tracking of the source, bases, or

disposition of written complaints about court and prosecutorial

operations. As noted above, a non-exhaustive list of

institutions receiving judicial system complaints included individual

courts and PPOs, the SCC, RPPO, the Councils, the Ministry of Justice,

and the ACA/APC. Each court was obligated to collect and submit

complaint statistics every six months to the MoJ, SCC, HJC, and its

immediately superior court. However, there was

no office in the system with unified numbers about written complaints

received during the period under review, how many complaints were

submitted to more than one institution, how many were ignored, or how

many were considered to be valid.

- The lack of statistics about the basis for complaints

left the system with little ammunition to counter rumors and perceptions

that the judiciary was riddled with corruption. While appeals

could be filed only if a party was not satisfied with the substance of a

court’s decision, complaints could be made if the party or other

participant believed the proceeding was being improperly prolonged, that

it was irregular, or that there had been an unauthorized influence on

the course or outcome of the case.

- Interviewees told the FR team reasons the two major

reasons for filing a complaint on court proceedings were dissatisfaction

with a decision and the length of proceedings. Once a written

complaint from any source reached a court president, he or she had to

get the response of the judge concerned and inform the complainant, as

well as the president of the immediately superior court, of the court

president’s own opinion and measures taken in response to the complaint.

This had to be done no later than 15 days after the court president

received the complaint. The court president could dismiss the complaint

in full or partly based on a finding that the complainant abused the

right to a complaint.

- If a complaint was filed through the Ministry of Justice,

the immediate superior court, or the High Judicial Council, the court

president also was obligated to notify that body about the merits of the

complaint and any resulting measures taken. However, none of

those bodies could overrule the decision of the court president or take

any further action if the court president had not acted on the

complaint.

- Complaints about the work of a Deputy Public Prosecutor

could be submitted to the Deputy Public Prosecutor, and about the work

of a Public Prosecutor to the superior Public Prosecutor. The

responding Public Prosecutor was required to provide a written decision

to the complainant within 30 days from the date of its receipt. If the complaint was submitted to

the SPC, MoJ, RPPO, or another superior PPO, these bodies also had to be

notified of the results. Citizens, legal entities, state bodies, and

bodies of the autonomous province and local self-government units could

submit complaints to PPOs about the handling of cases.

- As of December 2020, the websites of many courts

incorporated information from the MoJ’s website about the filing of

complaints; the MoJ information included a written guide, a model

complaint, and an infographic that explained the procedure

visually. The MoJ’s website made it clear that the procedures

did not apply to dissatisfaction with the legality or regularity of

court decisions. The SCC included information on complaints procedure

and a model complaint on its website

, and a model complaint could be found in the section of the RPPOs

website dedicated to regulations and models.

However, as of late 2020, the HJC, SPC, and PPOs had not included

information about filing complaints regarding the work of courts or

prosecutors on their websites.

Effectiveness of Ethical

Codes ↩︎

- From 2017 to 2022, Serbia made significant steps in

integrating ethical codes for judges and prosecutors into the regimes

governing their behavior. As of March 2022, GRECO found that

the 2015 recommendation on effective communication of the Code of Ethics

for judges, complemented by additional written guidance on ethical

questions, has been implemented satisfactorily.

GRECO reported that by late 2020 a large number of judges had gone

through awareness training on the “Guidelines for the prevention of

undue influence on judges”. In April 2022, GRECO noted that dedicated

training on ethical issues is not regularly organized for

judges.

- There were also other positive developments relating to

judicial and prosecutorial ethics. These included the posting

of 36 anonymized final decisions of the HJC’s Disciplinary Commission

“with specified interpretations serving as practical examples and

providing guidance on the ethical questions,”

and, as noted above, the SPC adopted a new Code of Ethics for Public

Prosecutors and Deputy Public Prosecutors, with accompanying guidelines,

in April 2021. The Judicial Academy integrated

training on the prosecutorial ethics code in its 2019 training

program, with 51 prosecutors participating

in ethical training in 2019.

- Confidential counseling was an official mechanism to

promote and support the ethical conduct of holders of judicial office

was established in the HJC, and a confidential adviser was appointed in

November 2021. Before 2018 there

were no clear mechanisms for judges to seek advice or counseling on

appropriate ethics-based conduct in particular cases.

In September 2018, the High Judicial Council finally adopted the Rules

of Procedure for its Ethical Board, eight years after the HJC adopted

its Code of Ethics. These rules required the Ethical Board to provide

written guidance on ethical issues with practical examples and

recommendations and to provide opportunities for judges to seek

confidential advice/counseling on appropriate conduct in particular

cases.

- Although the SPC entrusted confidential counseling to the

Ethical Board and appointed a professor as a confidential adviser, there

is no reported confidential counseling on ethical issues for

prosecutors. The prosecutorial Code of Ethics

allowed prosecutors to ask the Ethical Board of the SPC for an

interpretation of a particular ethical rule or advice or determination

of facts on given ethical issues. However, there was

no requirement that the consultation is confidential.

Disciplinary accountability ↩︎

- In large part, the

legal frameworks governing the disciplinary accountability of judges and

public prosecutors in Serbia conformed to international

standards. The major exception was the continued designation of

the Councils as the second-instance disciplinary bodies, particularly

since the Councils also elect members of the respective Disciplinary

Commissions for judges and prosecutors.

The normative framework also received criticism from domestic sources

for being incoherent and inconsistent,

based on at least two issues. The first criticism was that Law on Judges

was not explicit about the disciplinary accountability of court

presidents who did not implement the rules and regulations they were

required to apply. The second dealt with the lack of definitions for

terms used in the description of offenses, e.g., “serious,” “severe,” or

“to a great extent.” This criticism is not only an

academic concern since judges and prosecutors were sanctioned under

those provisions. The EU urged Serbia to amend the

disciplinary rules for both judges and prosecutors in line with European

standards, so only serious misconduct and not mere incompetence could

give rise to disciplinary proceedings.

- According to the data of the High Judicial

Council, from 2015 to 2020, there

were 90 disciplinary proceedings initiated against judges before the HJC

Disciplinary Commission. This is shown in Table 20. During the

same period, 27 disciplinary proceedings were initiated against public

prosecutors and deputy public prosecutors before the Disciplinary

Commission of the State Prosecutorial Council,

as shown in Table 21.

Table 20:Number of complaints to the disciplinary prosecutor and

initiated disciplinary proceedings against judges

| Year |

Number of complaints to the disciplinary

prosecutor |

Disciplinary proceedings initiated |

| 2015 |

956 |

18 |

| 2016 |

831 |

19 |

| 2017 |

N\A |

15 |

| 2018 |

584 |

14 |

| 2019 |

491 |

14 |

| 2020 |

429 |

10 |

Table 21: Number of complaints to the disciplinary prosecutor and

initiated proceedings against public prosecutors and deputy public

prosecutors

| Year |

Number of complaints to the disciplinary

prosecutor |

Disciplinary proceedings initiated |

| 2015 |

262 |

8 |

| 2016 |

197 |

4 |

| 2017 |

179 |

3 |

| 2018 |

152 |

5 |

| 2019 |

162 |

7 |

| 2020 |

111 |

0 |

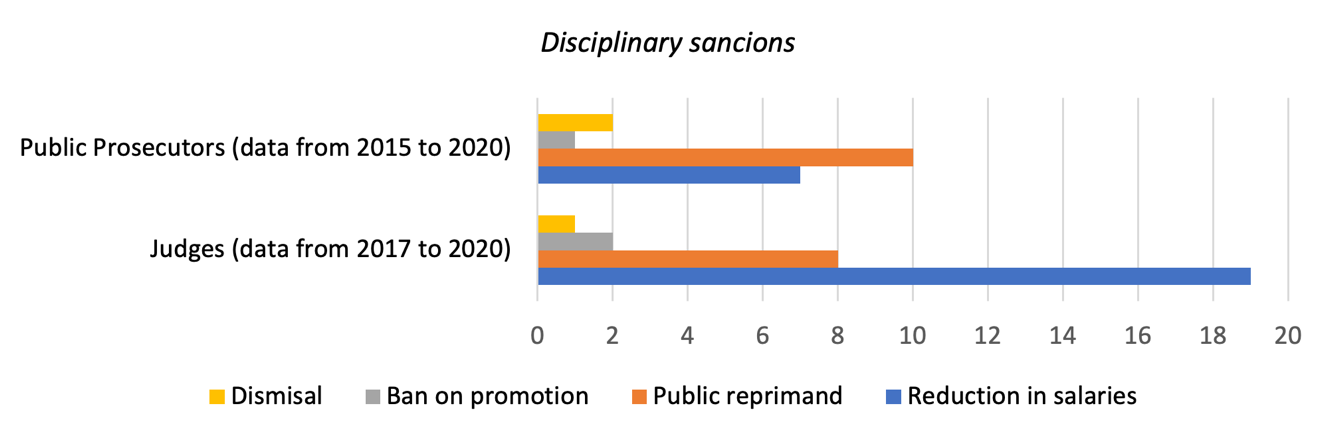

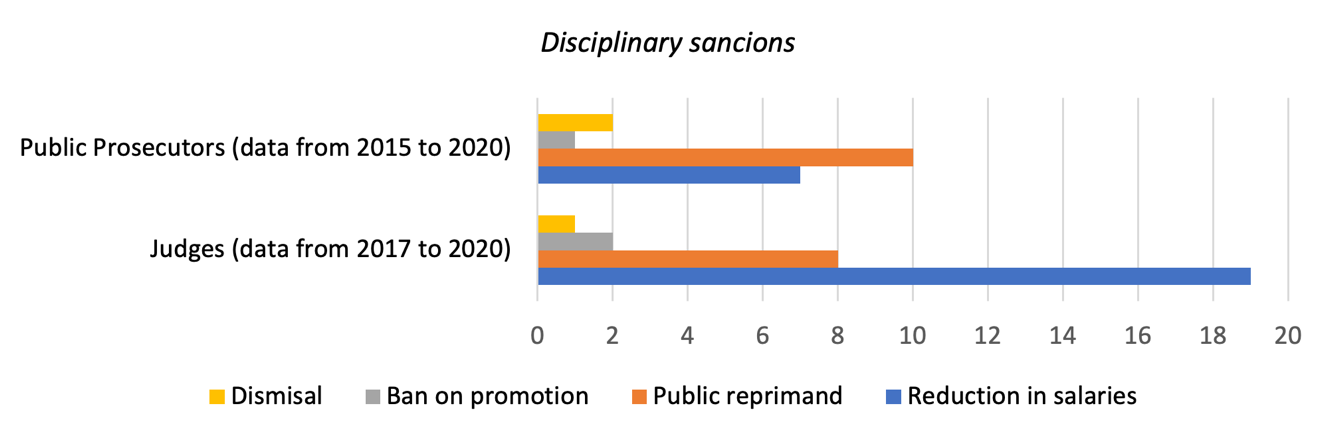

- Disciplinary sanctions for judges and public prosecutors

included public reprimand, reduction in salary, and the prohibition of

promotion and termination, although the most common sanctions were

public reprimand and salary reduction. See Figure 115.

Figure 115: Number of disciplinary sanctions imposed on judges and

public prosecutors

Source: Annual Reports of the High Judicial Council and the State

Prosecutorial Council

- The most common disciplinary offenses for which judges

were sanctioned related to efficiency and violations of the applicable

ethical codes. Judges were found responsible for (1) negligent

performance of judicial duties related to the conduct or the completion

of legal proceedings, especially unreasonable extension of proceedings,

(2) delays in drafting decisions, and (3) failing to schedule hearings

or trials. In 2017 and 2018, there were three cases in which judges were

found responsible for “violation of provisions of the Ethical Code to a

great extent”.

- There also were no details available about individual

prosecutorial disciplinary proceedings.

The SPC reported that from 2015 to 2018, public prosecutors and deputy

public prosecutors were found responsible for (1) failing to render

prosecutorial decisions and file ordinary and extraordinary legal

remedies within stipulated time limits; (2) manifestly violating rules

of procedure relating to the respect to be shown to judges, parties,

their legal counsel, witnesses, staff, or colleagues; (3) violating the

principle of impartiality and thereby jeopardizing the public’s trust in

the public prosecution, and (4) “serious violations of the Ethical

Code.”

Training on

Ethics and other Aspects of Integrity ↩︎

- Training covering ethics and integrity was incorporated

into the JA curricula for both initial

and continuous training

of judges and prosecutors. While the Academy was

responsible for providing the training, the Councils were responsible

for defining the initial training curricula, approving the curricula for

the continuous training of holders of judges and prosecutors, and

monitoring training plan implementation.

The prosecutors‘ Code of Ethics, in effect before 2021, also was

promoted among public prosecutors and their deputies by the JA, which

integrated the code into its 2019 Training Program.

- The JA’s initial training curricula covered ethics and

integrity as part of the classes on "Professional Knowledge and Skills,

EU Law and International Standards." As described in JA

material, the two-day workshops consisted of lectures and debates and

were designed to cover regulations governing the selection, dismissal,

and professional ethics of judicial officials.

- According to the 2018 and 2019 Judicial Academy

Reports, “Ethics and Integrity in

the Judiciary” were one of the most frequently covered thematic areas

within the JA’s continuous training curricula “Special Knowledge and

Skills.” In 2018, this “Ethics and Integrity” theme included

one day of training about the ethics of public servants, judicial

ethics, and prosecutorial ethics. In 2019, training on the undue

influence of prosecutors and judges was added, and for 2020 the

curricula added the consideration of professional ethics as a tool for

preventing corruption. See Table 21 and Table 22. The chapter on

Commercial Law also included a workshop for judges and judicial

associates and assistants of Commercial Courts on judicial

ethics.

Table 22: Training conducted in 2018 for the Chapter “Special

Knowledge and Skills”

| Mentorship |

21 |

| Ethics and Integrity in the Judiciary |

18 |

| Administration in Courts and PPOs |

4 |

| Economic Education of Public Prosecutors |

4 |

| Public Relations and Communication |

4 |

| Economic Education |

3 |

| Improving training |

3 |

| Protection and Support of Witnesses |

3 |

| Public Relations and Communication; Assistance and Support to

Victims, Injured Parties, and Witnesses, and Protection and Support of

Witnesses. |

1 |

Source: The 2018 Judicial Academy Report

Table 23: Training conducted in 2019 for Chapter “Special Knowledge

and Skills”

| Ethics and Integrity in Judiciary |

41 |

| Resolving Backlogged/Aging Cases |

18 |

| Public Relations and Communication |

15 |

| Training for Using of the Electronic Database of Case Law |

4 |

| Mediation |

2 |

| Improving training |

2 |

Source: The 2019 Judicial Academy Report

Table 24: Number of judges and prosecutors participating in

training

on ethics and integrity from 2016 to 2018.

| 2016 |

96 |

89 |

| 2017 |

94 |

91 |

| 2018 |

184 |

94 |

| Total |

374 |

274 |

Source: Annual Reports of the Judicial Academy

- From 2018 to 2020, the continuous curricula shifted to

include more skills-based training on ethics and integrity.

This was done with the assistance of the EU-funded

project Prevention and Fight Against Corruption. This training aimed to provide

participants with skills to identify and resolve ethical dilemmas and

risk situations in practice by application of the Ethical Code and

anti-corruption tools and covered issues of conflict of interest and

gift-giving. According to the 2019 Judicial Academy report, 16 one-day

training sessions were held with the support of the EU project, and in 2020, the JA included this

training program in the continuous training curricula.

However, the training program was not mandatory for all judges and

prosecutors.

- The topic of undue influence on judges and prosecutors

also was incorporated into the 2019 continuous training curricula for

the first time. The Judicial

Academy’s first training needs assessments (TNA) of program users,

conducted in 2018, was a primary source for the contents of the 2019

continuous training curricula.

The TNA identified ethics and integrity training as a top priority for

judges of higher courts and deputy appellate

public prosecutors. The 2019 curricula covered

preventing the risk of undue influence and protection of judges and

training of trainers for preventing the risk of undue influence and

protection of prosecutors. The training was in addition to the

distribution of “Guidelines for the Prevention of Undue Influence on

Judges” to all judges in February 2019

and several awareness-raising programs held for judges about the

guidelines. However, the training on

preventing the risk of undue influence and protection of judges was not

included in the 2020 training curricula.

Views of

Integrity Within the Delivery of Justice Services ↩︎

Perception of Trust and

Confidence ↩︎

- The 2020 Regional Justice Survey showed a significant

increase in the trust of Serbian citizens in their judicial system

compared to 2009 and 2013. The judicial system was in the

middle of the 2020 ladder of trust, at 55 percent (see Figure 116). This

improvement was part of a pattern of increased trust in state

institutions generally, with the exception of media. Trust in the

judicial system increased both among court users and the general public

(see Figure 117).

Figure 116: Citizen Trust in Institutions, 2009, 2013 and 2020

Figure 117: Citizens’ Trust in the Serbian Judicial System, 2009,

2013 and 2020

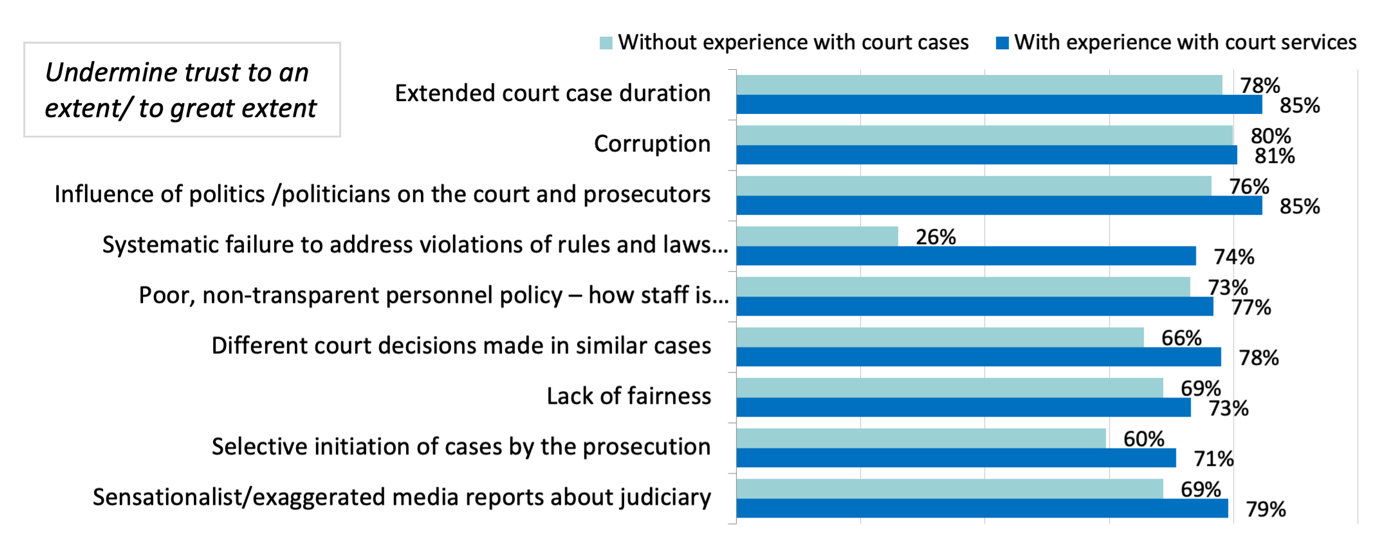

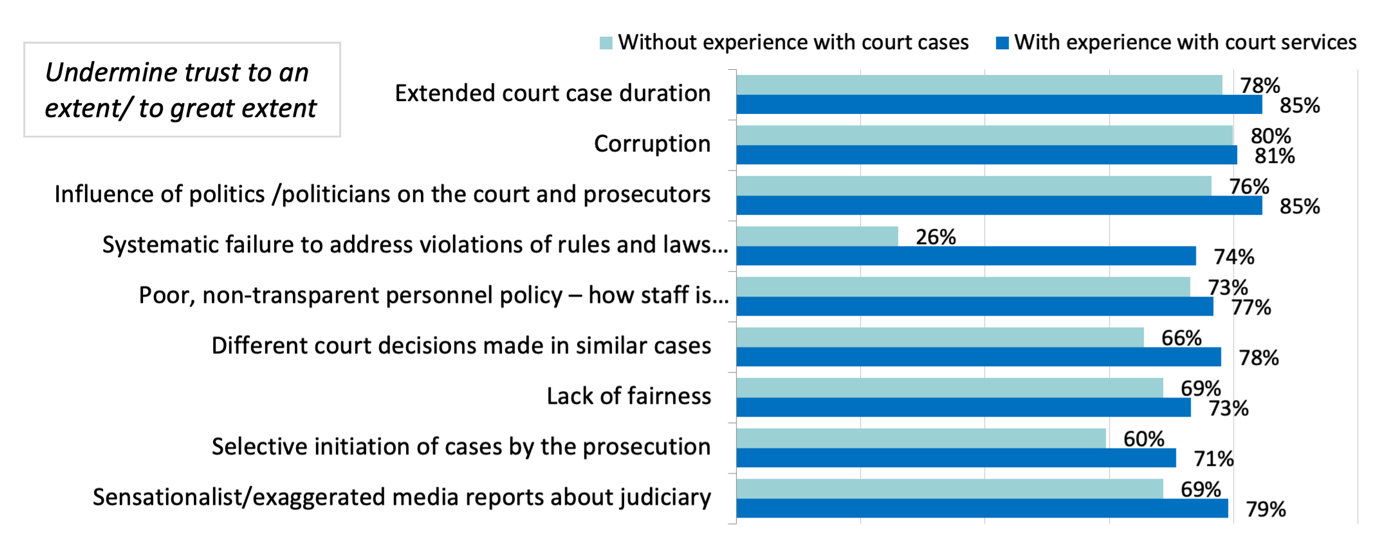

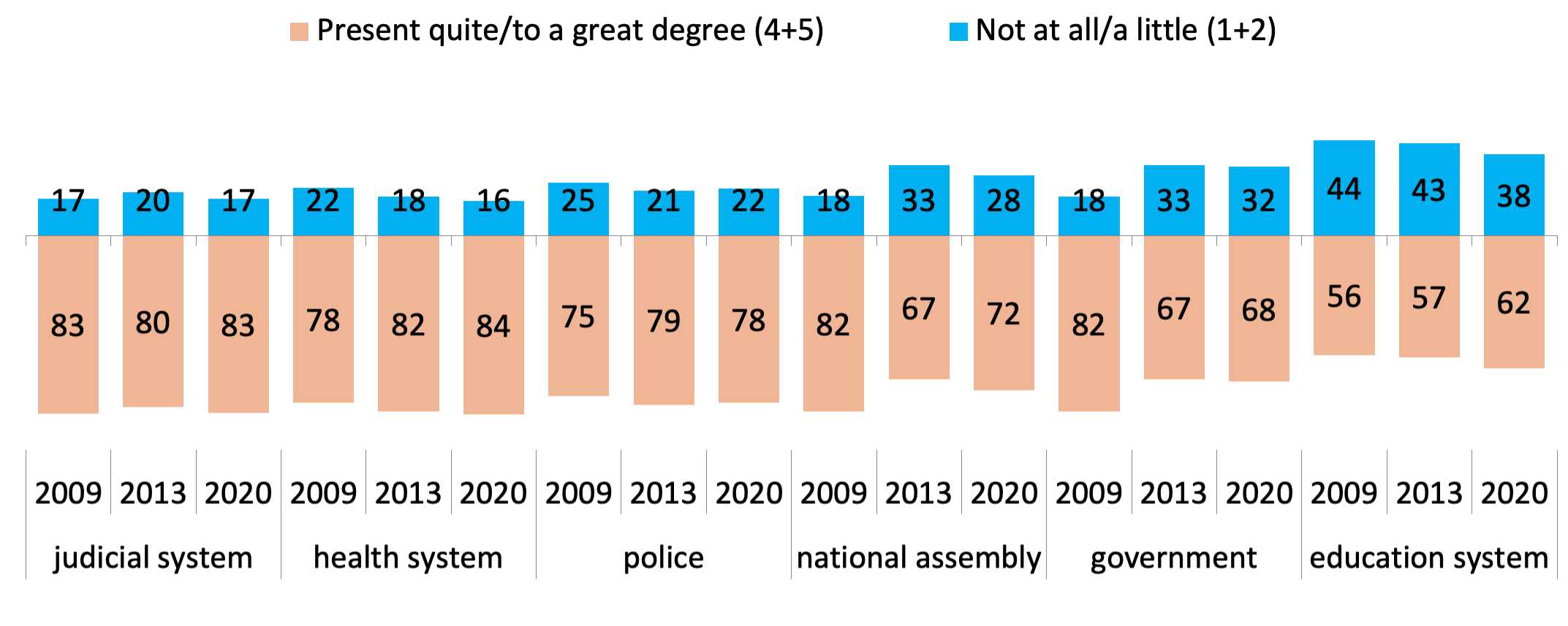

- A variety of factors continues to undermine citizens’

trust in the judicial system. Eighty percent of respondents

selected the length of proceedings, corruption, and political influence

as reasons for their lack of trust, and more than 70 percent also named

poor and non-transparent personnel policies. Other factors cited were

different results reached in similar cases, lack of fairness, and the

selective initiation of cases (see Figure 118). Some of these factors

were mentioned more often by the court users than by members of the

general public, such as systematic failures to address violations of

rules. Based on the similarity between the factors selected by

respondents in the 2013 Multi-Stakeholder Justice Survey and the factors

selected by respondents in 2020, it appears judicial stakeholders still

have significant work to do in addressing these issues.

Figure 118: Are the following issues present in the judicial

system?

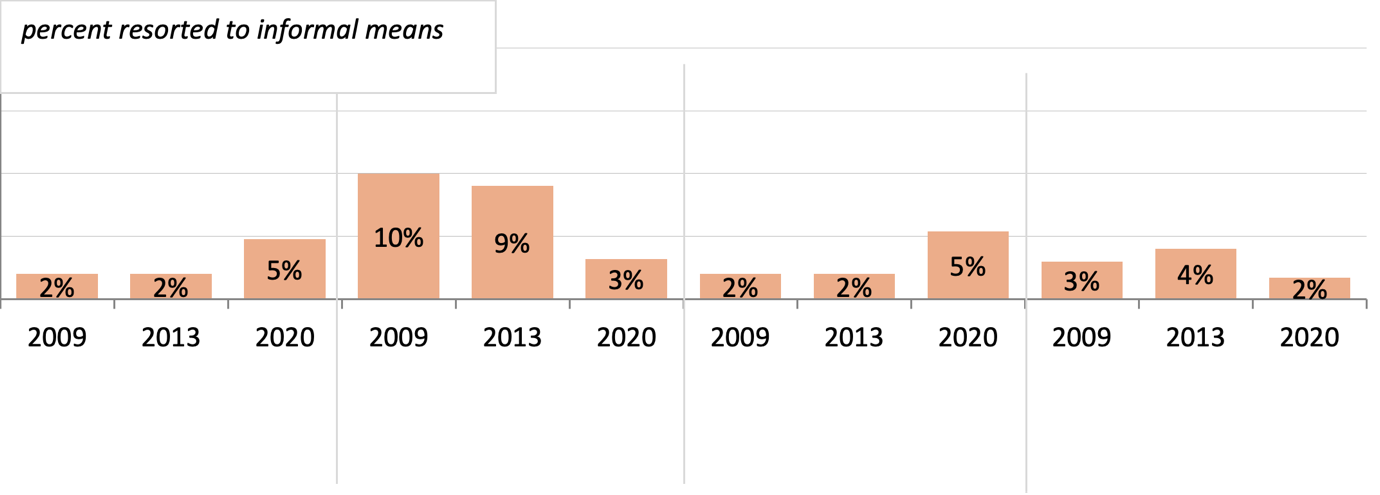

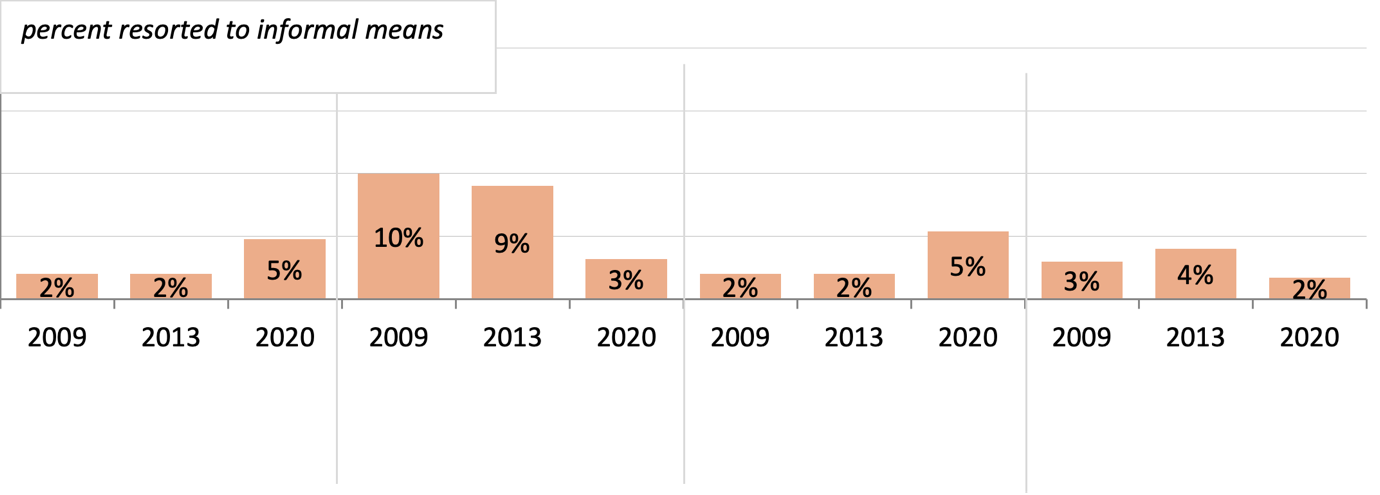

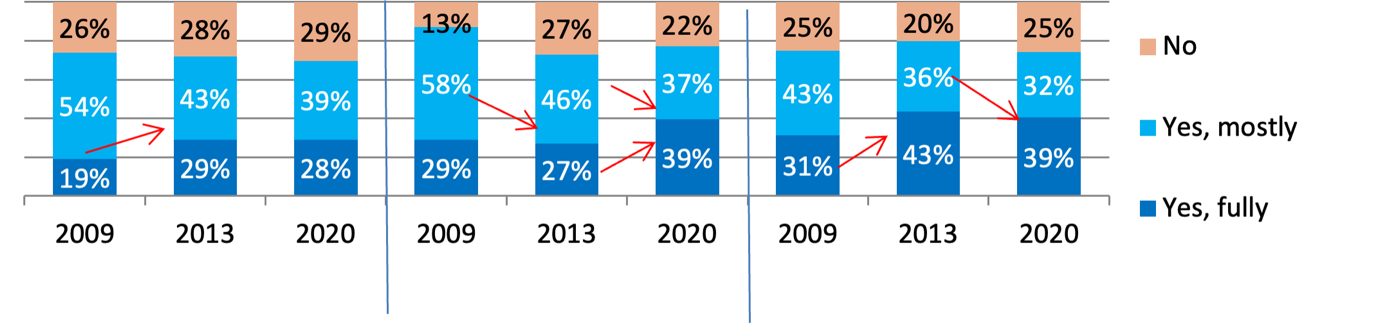

- The Survey results suggest that most attempts to

influence judges and prosecutors are more sophisticated than outright

bribery, although some court users surveyed in 2020 still admitted to

using informal means to advance their cases, compared to those surveyed

in 2013, as shown in Figure 119 below. Three

percent of court users in misdemeanor cases reported using informal

means to advance their case in misdemeanor cases, compared to nine

percent of the court user respondents in 2013. There also was a drop of

two percent of court users in business cases willing to make the

admission. However, there was an increase from two percent in 2013 to

five percent in 2020 of respondents admitting to using informal means to

advance their civil and criminal cases.

Figure 119: Court Users Who Reported Using Informal Means to Advance

their Case, 2009, 2013 and 2020

- According to the 2020 USAID GAI Citizens’ Perceptions of

Anti-Corruption Efforts in Serbia,

roughly 10 percent of citizens reported they gave a gift, paid a

bribe or did a favor for personnel in courts and prosecution

offices. Among those, the majority said they offered a bribe to

obtain faster service, while others wanted a service they were not

entitled to, or they sought to avoid responsibility for their

actions.

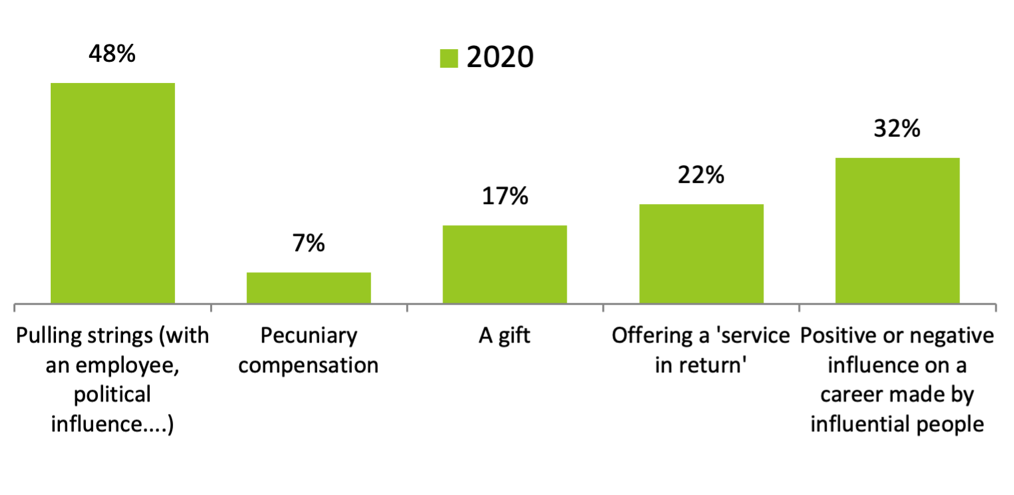

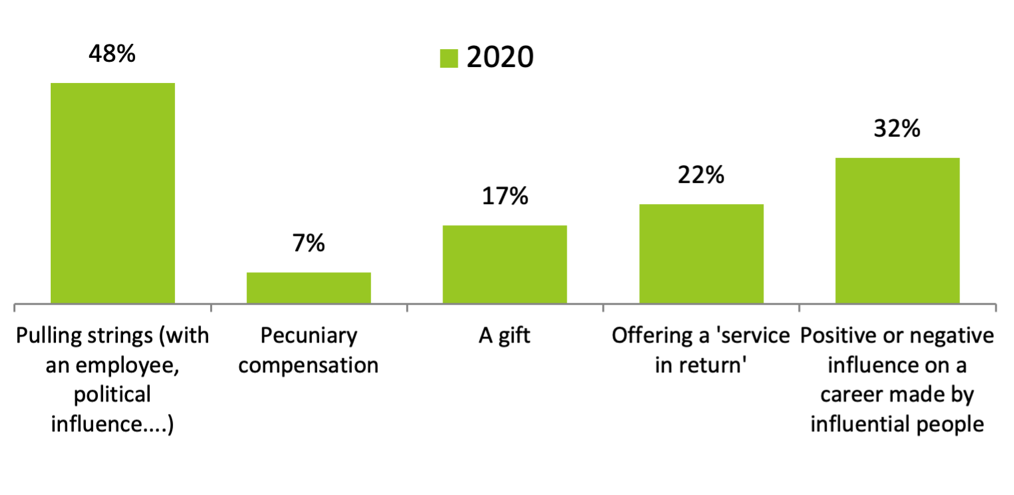

- Attempts to unduly influence the judiciary come from a

range of sources and via a range of means. In the Regional

Justice Survey, judges and prosecutors identified the most common

situations they encountered in which an individual tried to resort to

informal means to affect their work as pulling strings through political

influence or through an employee. See Figure 120 and Figure 121 below.

Thirty-two percent of judges and 25 percent of prosecutors reported

influential people had influenced their career (not necessarily in a

positive way) during the past year, and 22 percent of judges and 17

percent of prosecutors reported offering a ‘service in return’. Gifts

and pecuniary compensation were the most infrequently reported forms of

corruption.

Figure 120: Share of judges who report experiencing the following

practices in the last 12 months

Figure 121: Share of prosecutors who reported experiencing the

following practices in the last 12 months

Perceptions of Corruption ↩︎

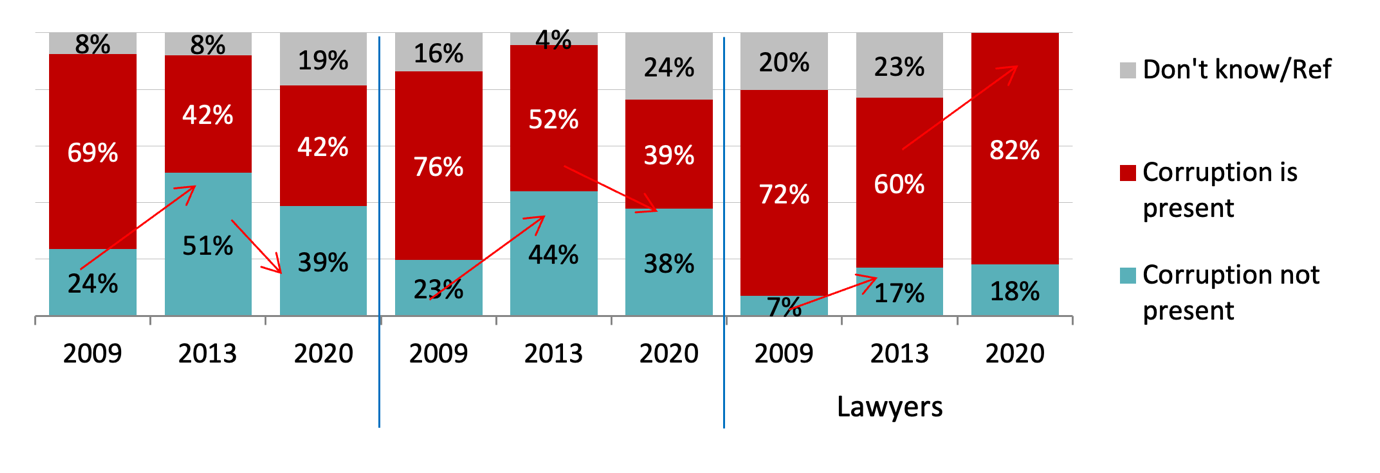

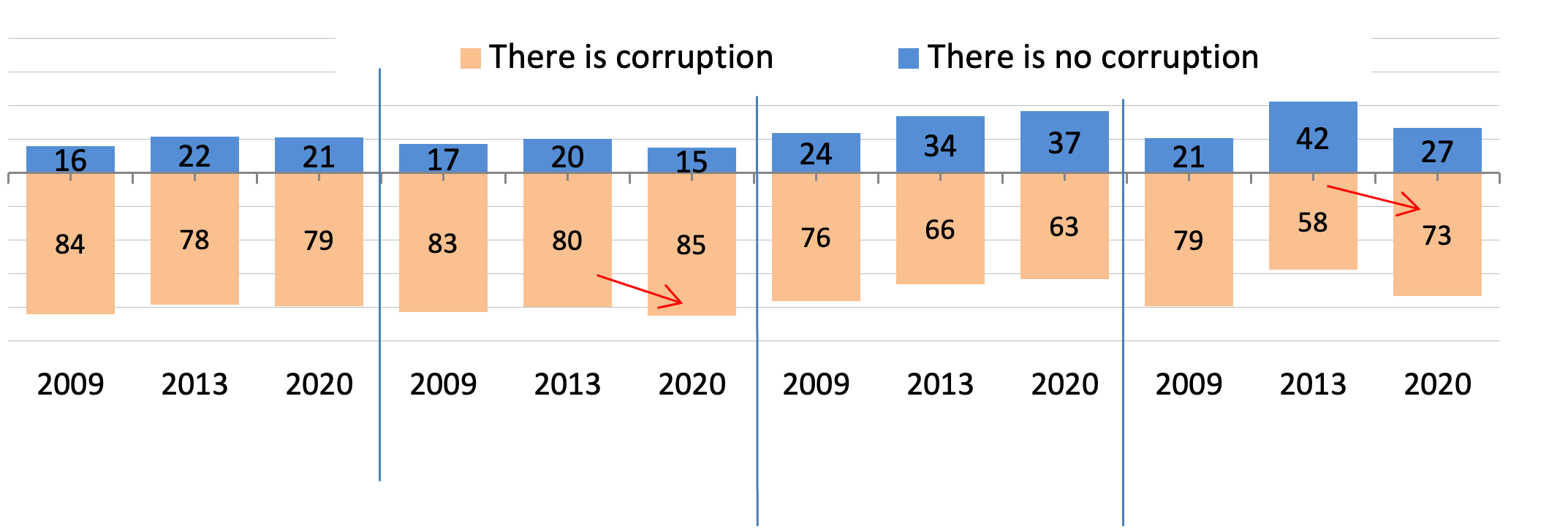

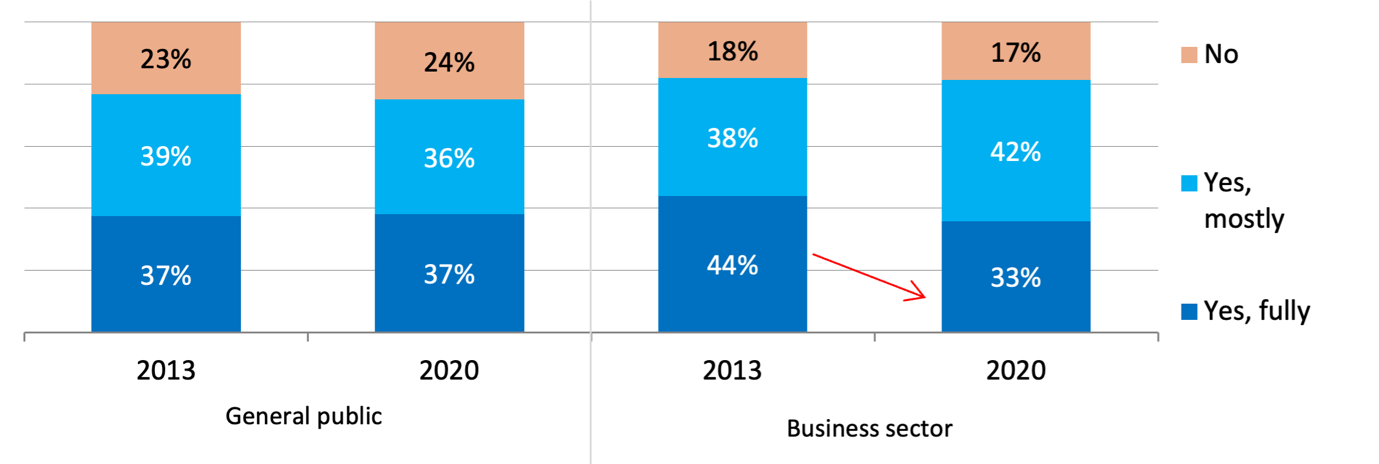

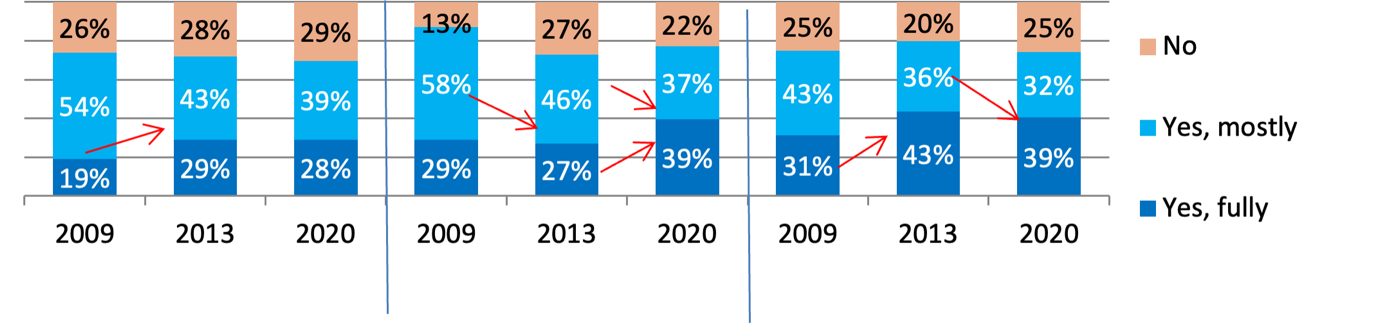

- Although trust in the judicial system had increased in

2020, there remains a widespread perception that corruption within the

Serbian judiciary is pervasive, and the levels of perceived corruption

are not improving either within or outside the judicial system.

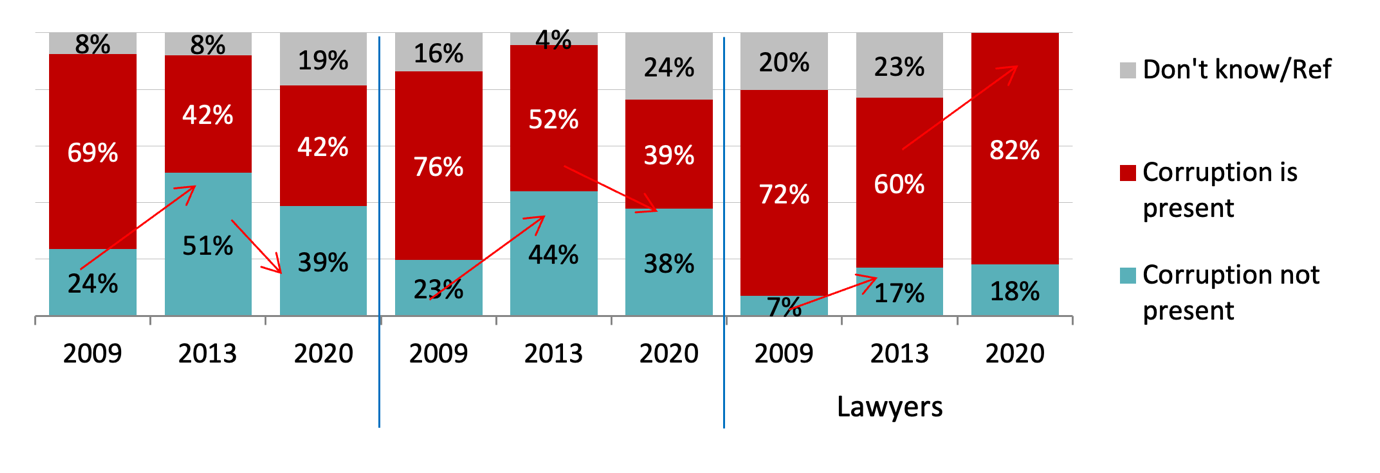

More than 80 percent of the citizens surveyed, 42 percent of judges, and

39 percent of prosecutors believe corruption is present in the judiciary

(see Figure 122 and Figure 123). In response to other survey questions,

businesses also report that corruption poses an obstacle to their

operations.

- The percentage of those who reported that corruption is

present in the judicial system remained the same for judges from 2013,

decreased substantially for prosecutors, and increased substantially for

lawyers. There also was a substantial increase in 2020 in the

percentage of judges and prosecutors who refused to say whether they

thought corruption was present or could not assess the situation. On the

other hand, lawyers apparently had no problem stating their opinions.

Figure 122: Perception of Corruption in the Judiciary among Judges,

Prosecutors and Lawyers, 2009, 2013 and 2020

Figure 123: General Perception of Corruption in the Judiciary, 2009, 2013 and 2020

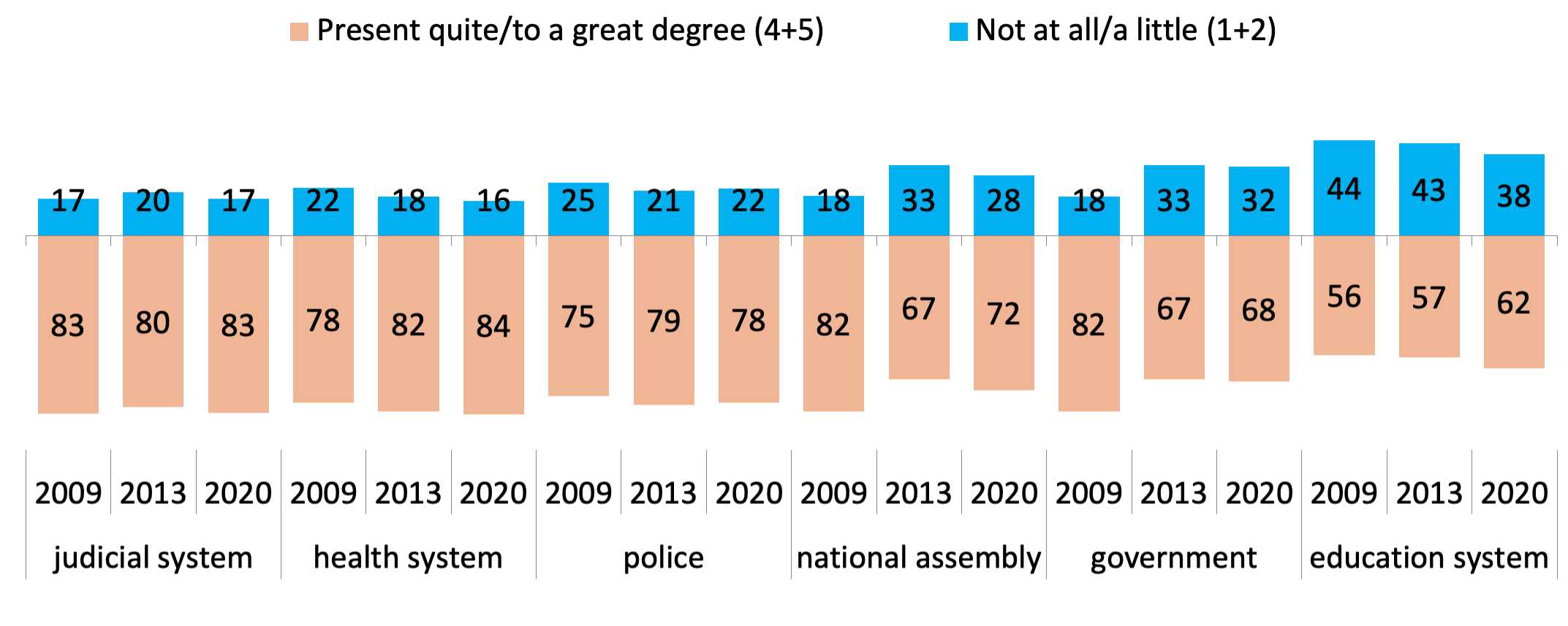

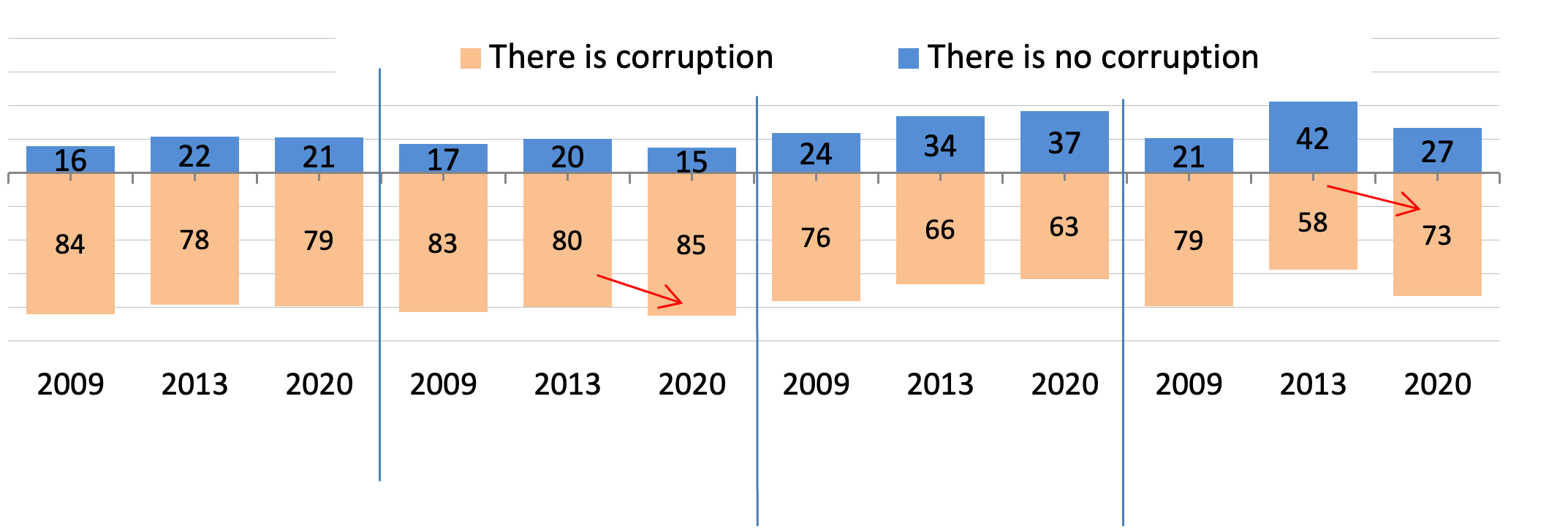

- For citizens, the judiciary is second only to the health

system as the institution most affected by corruption, as shown in Figure

124. These are the only two institutions for which the majority

of citizens report that corruption is present to a considerable degree

(rated at 4 or 5).

Figure 124: General Perception on the Presence of Corruption in State

institutions, 2009, 2013 and 2020

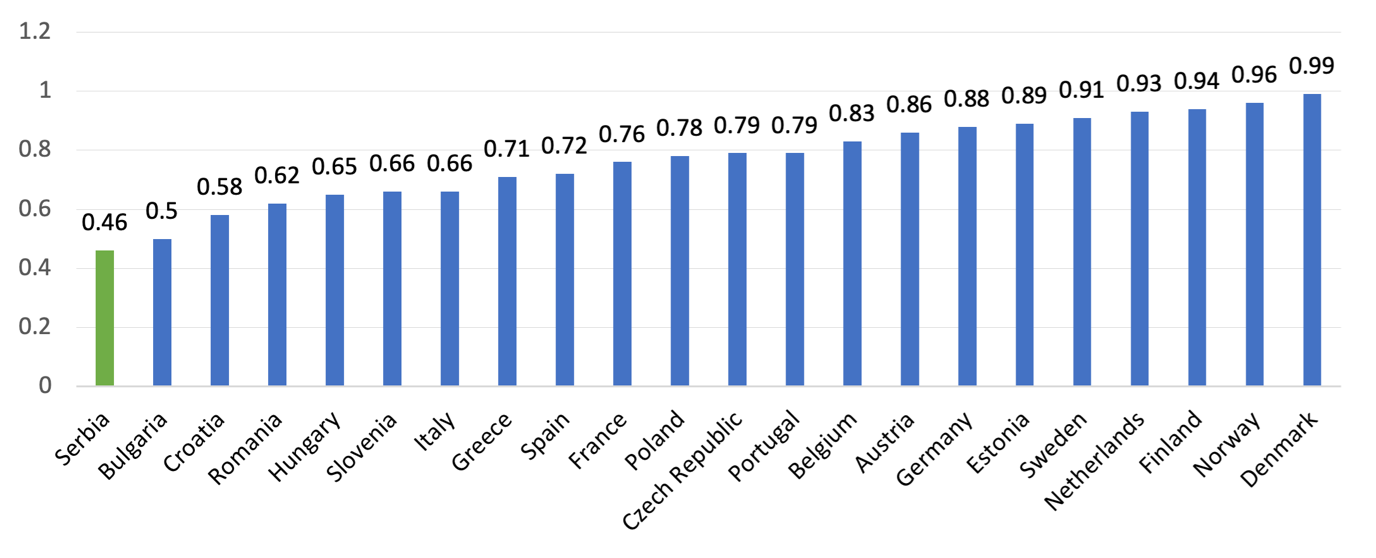

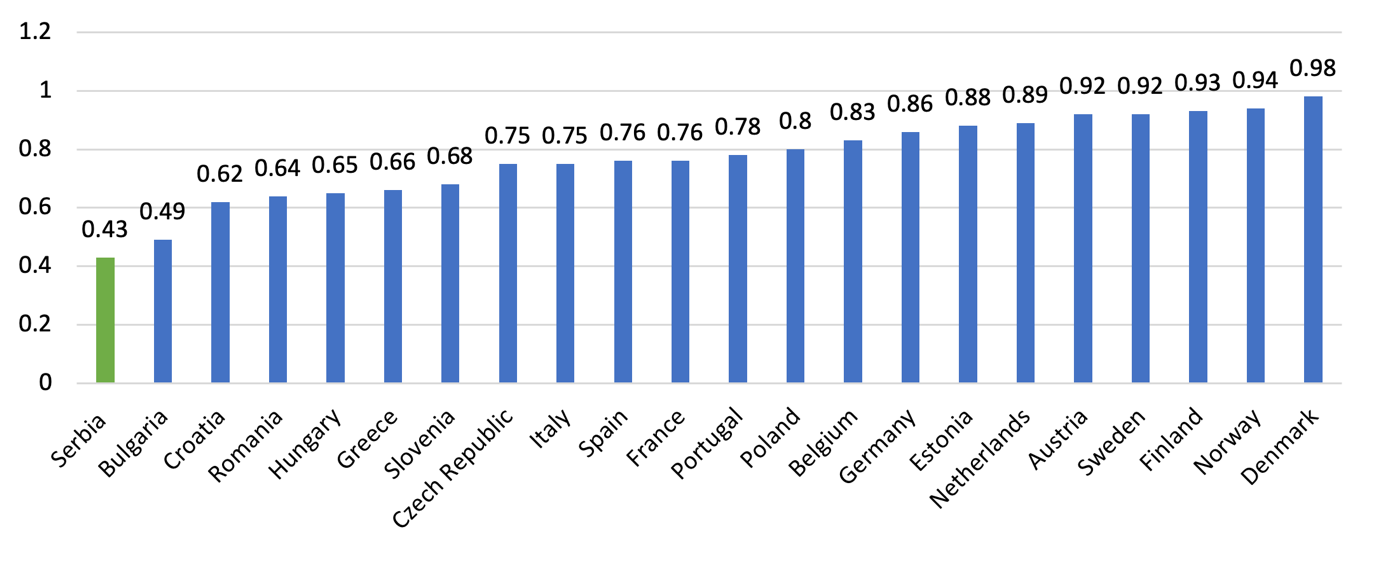

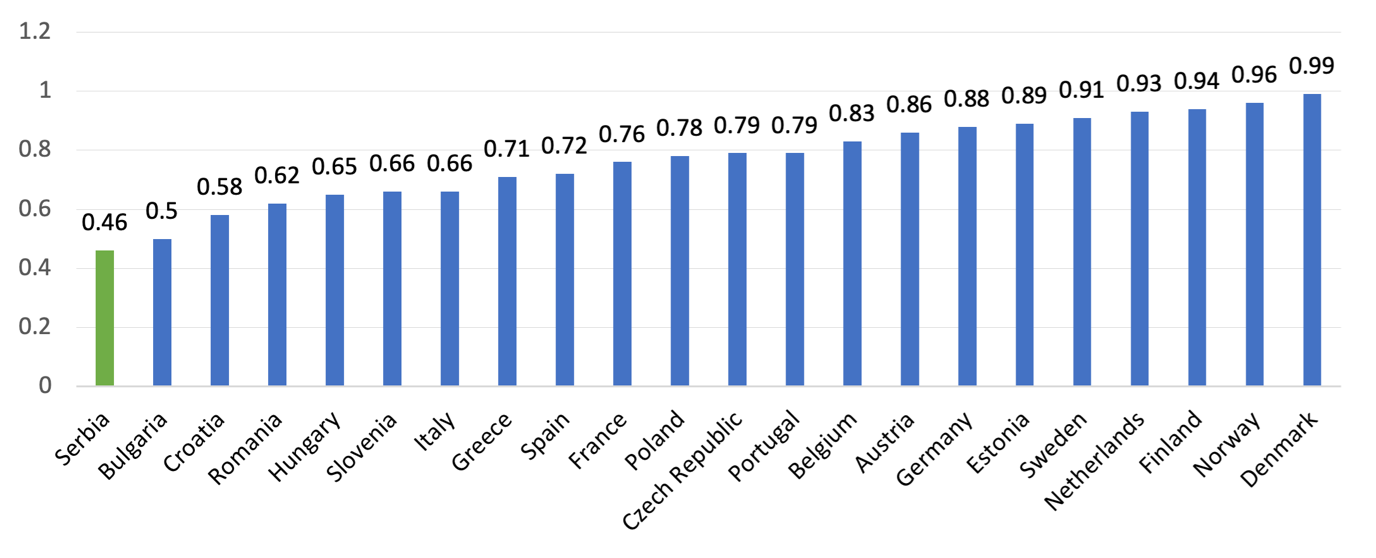

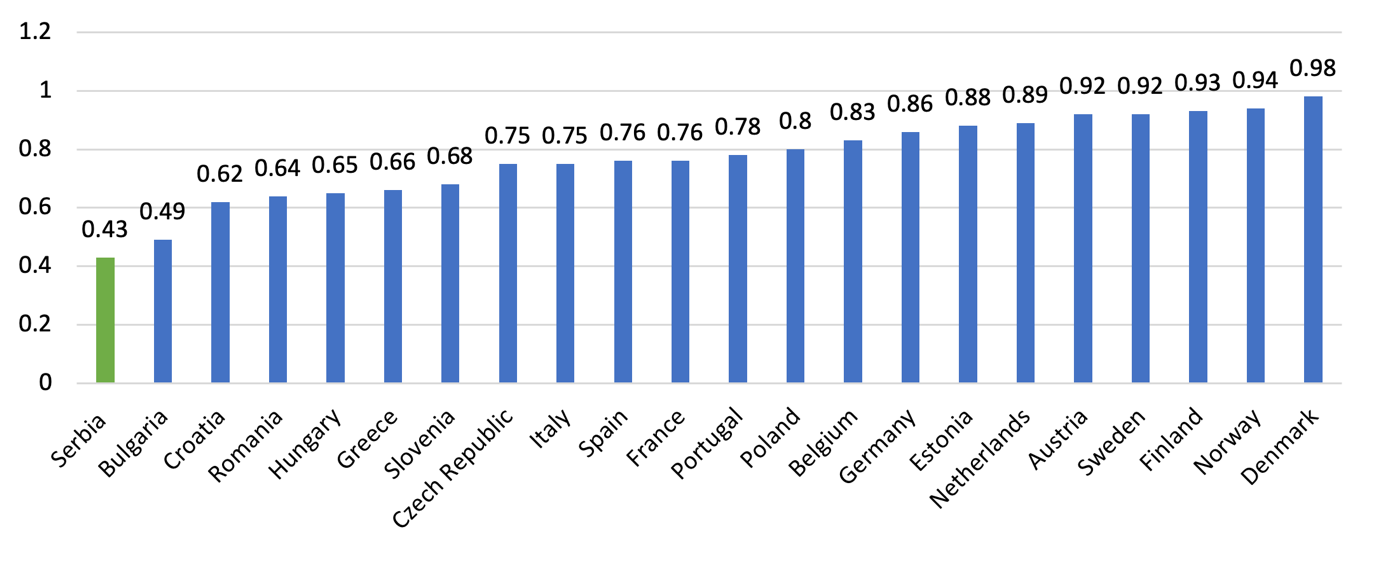

- The World Justice Project Rule of Law Index 2020 also

examined perceptions of corruption in both civil and criminal

cases. In civil cases, Serbia scored 0.46

and ranked behind all EU countries (73 out of 128 countries included in

the Index). In criminal cases, Serbia scored 0.43 and again ranked

behind all EU countries (see Figure 125).

Figure 125: 2020 World Justice Project, Perception that Civil System

is Free of Corruption (1 = no corruption), Serbia and EU

Figure 126: 2020 World Justice Project, Perception that Criminal

System is Free of Corruption (1 = no corruption), Serbia and EU

Perceptions of Judicial

Independence ↩︎

- A range of legal safeguards exists to protect the

independence of the judiciary, but reforms to remove vestiges of

dependence have been delayed, as discussed in the

Governance and Management Chapter. Among other changes, draft

Constitutional amendments which have been proposed would remove the

Assembly’s approval of judicial appointments.

- A significant portion of judges and prosecutors report

the judicial system is not independent in practice.

Approximately 24 percent of judges and 34 percent of prosecutors

reported that the judicial system is not independent. Lawyers are even

more skeptical, with 73 percent of lawyers reporting the judicial system

is not independent, as shown in Figure 127.

Figure 127: Lawyers, judges, prosecutors: the perception of

independence of the justice system

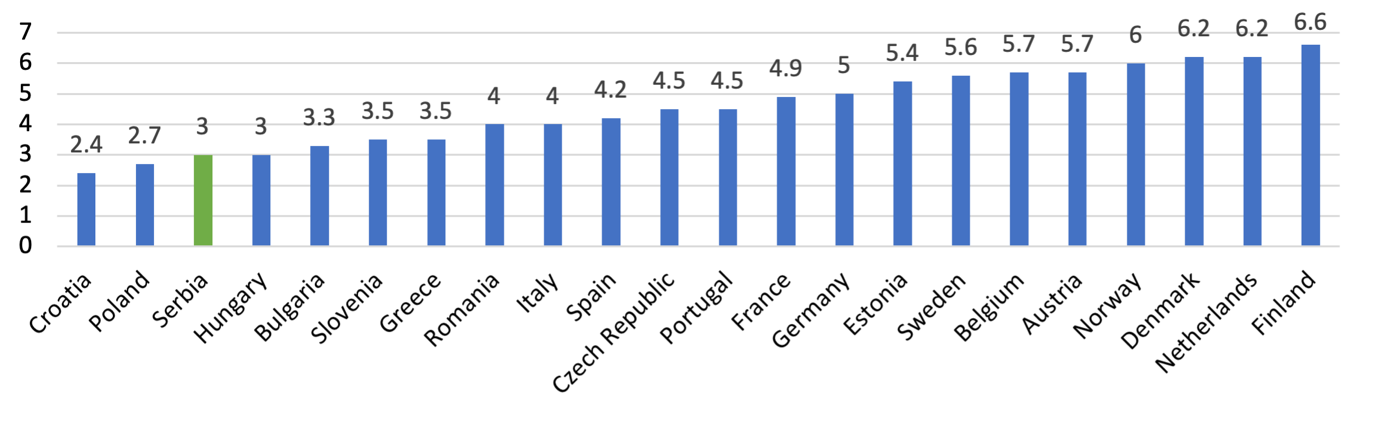

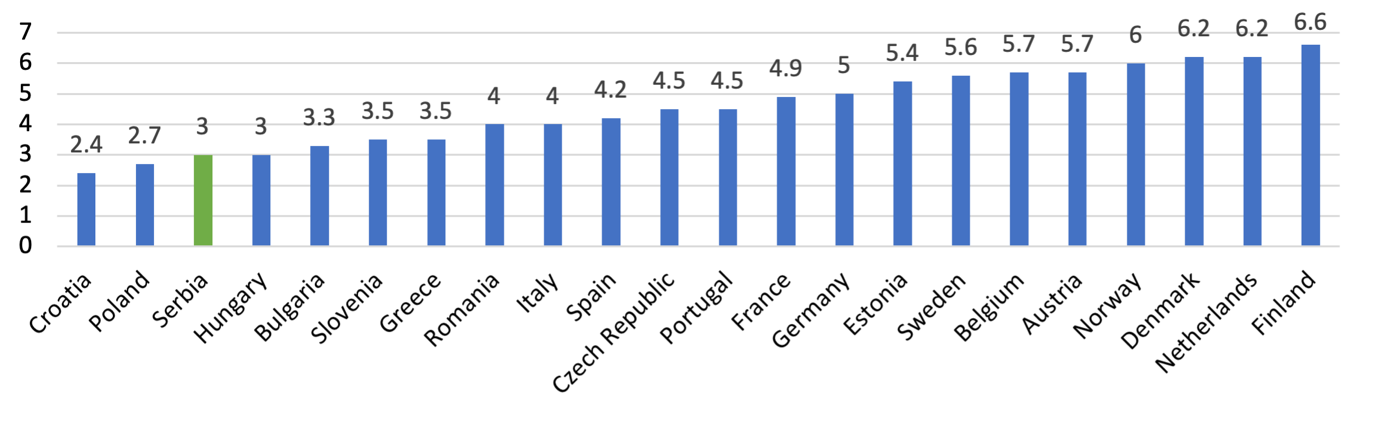

- The 2019 World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness

Report ranked Serbia’s judiciary

101th out of 141 countries for judicial

independence. Serbia fell behind all EU countries except

Croatia and Poland. The results are similar in the 2014 Bertelsmann

Transformation Rule of Law Index, in which Serbia

ranked below all the countries of the EU11: its score for Serbia’s

judicial independence was 6.0 out of 10 in 2014 and remained unchanged

from 2009.

Figure 128: 2019 WEF Global Competitiveness Report, Judicial

Independence in the EU and Serbia

Perceptions of

Impartiality and Fairness ↩︎

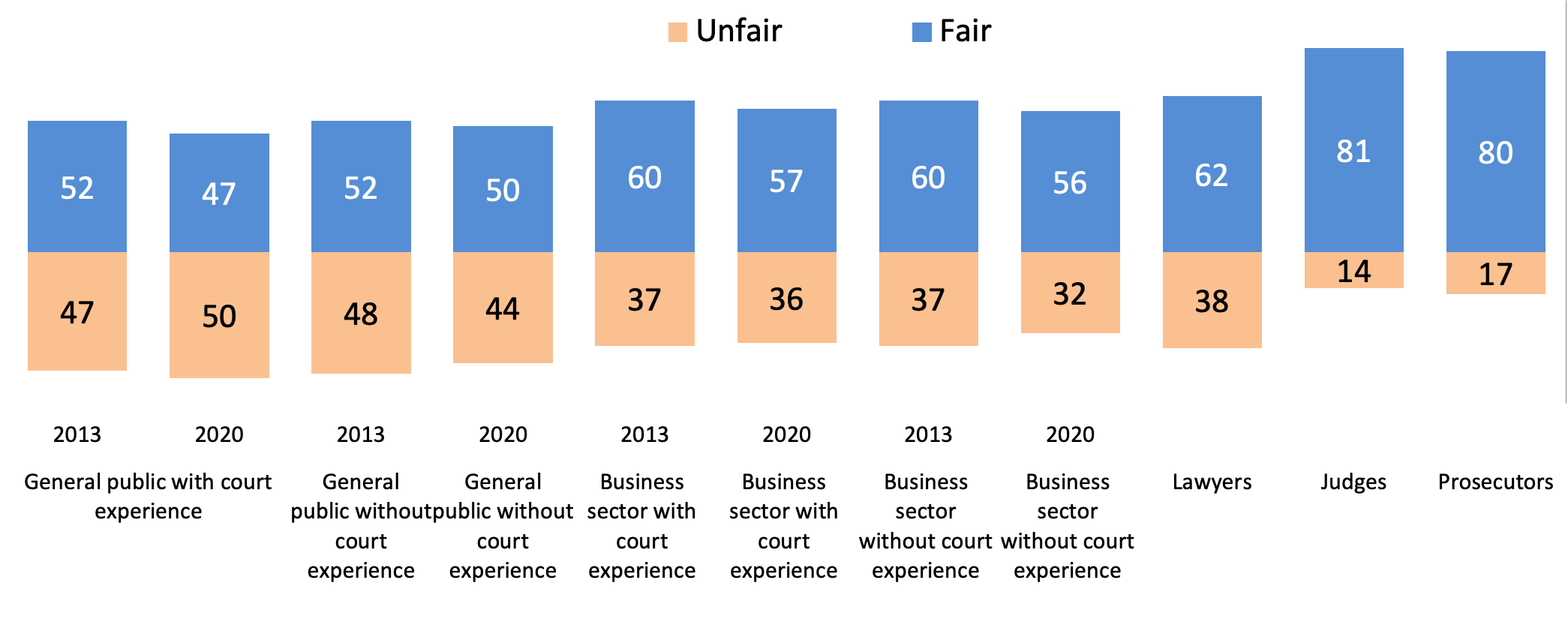

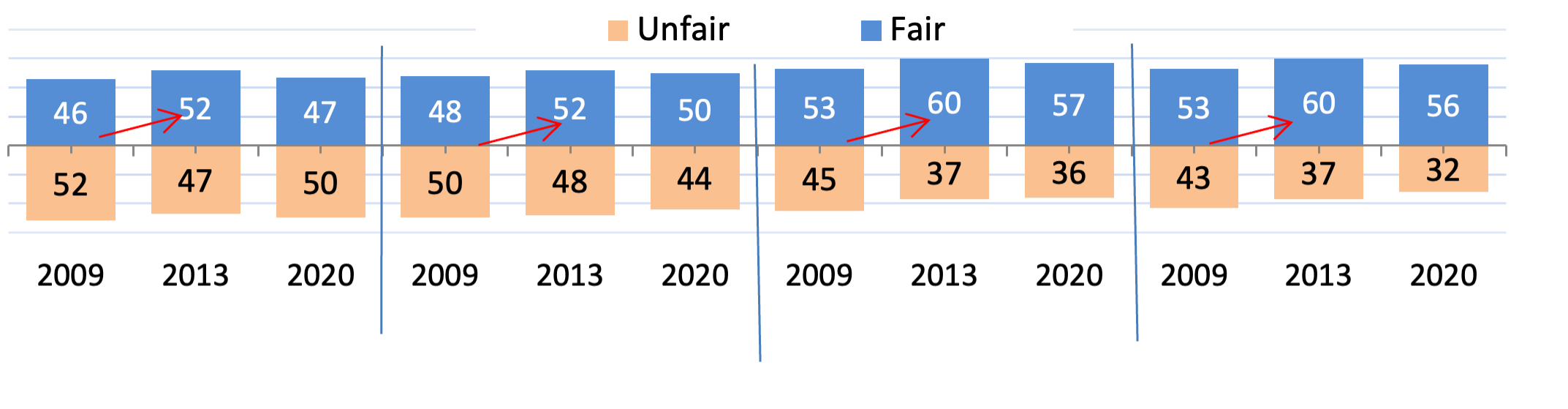

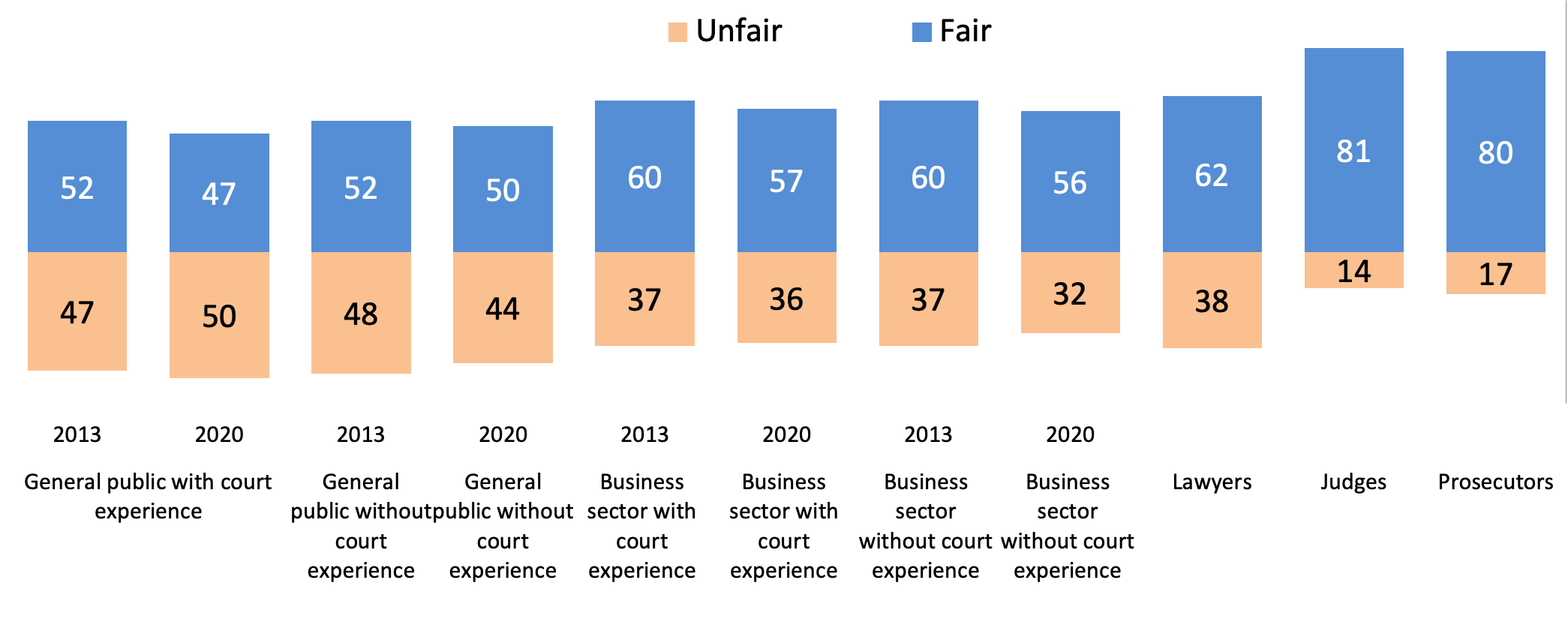

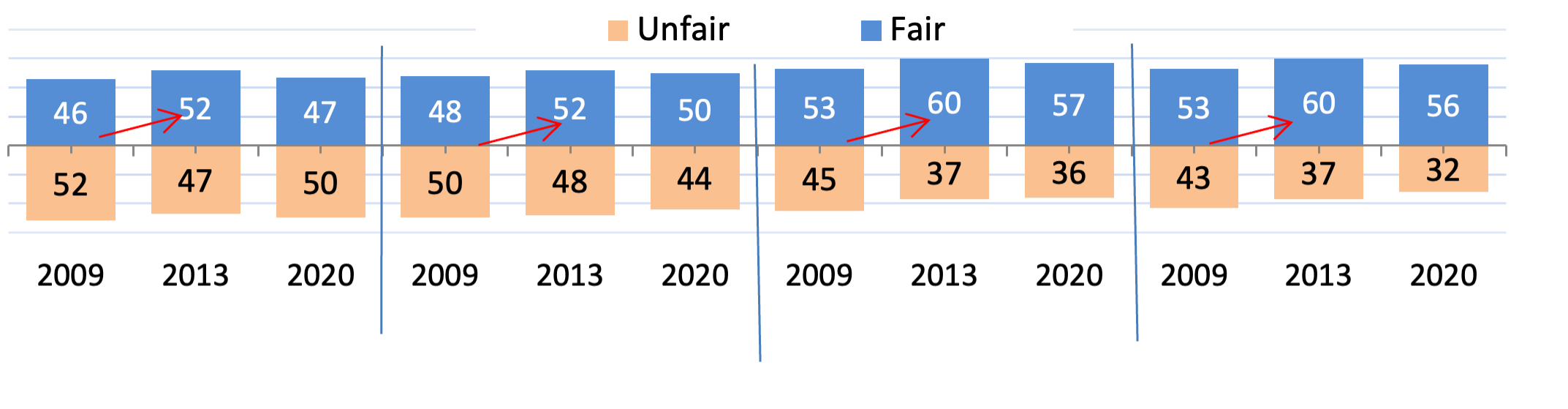

- Perceptions of the fairness of the judicial system varied

widely. Only 47 percent of the public, 57 percent of business

representatives, and 62 percent of lawyers consider the system to be

fair. These were small decreases compared to the results of the 2013

survey. In contrast, about 80 percent of judges and prosecutors

evaluated the system as fair in 2020, as shown in Figure 129.

Figure 129: Public Perceptions of Fairness of the Judiciary, 2013 and

2020

Figure 130: Perception of Fairness in Court User’s Case, 2013 and

2020

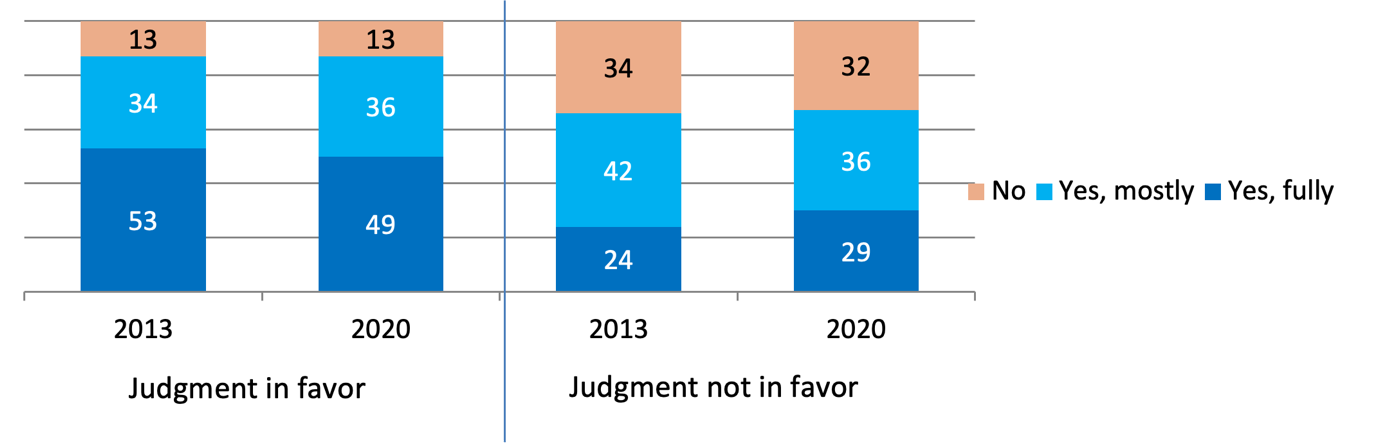

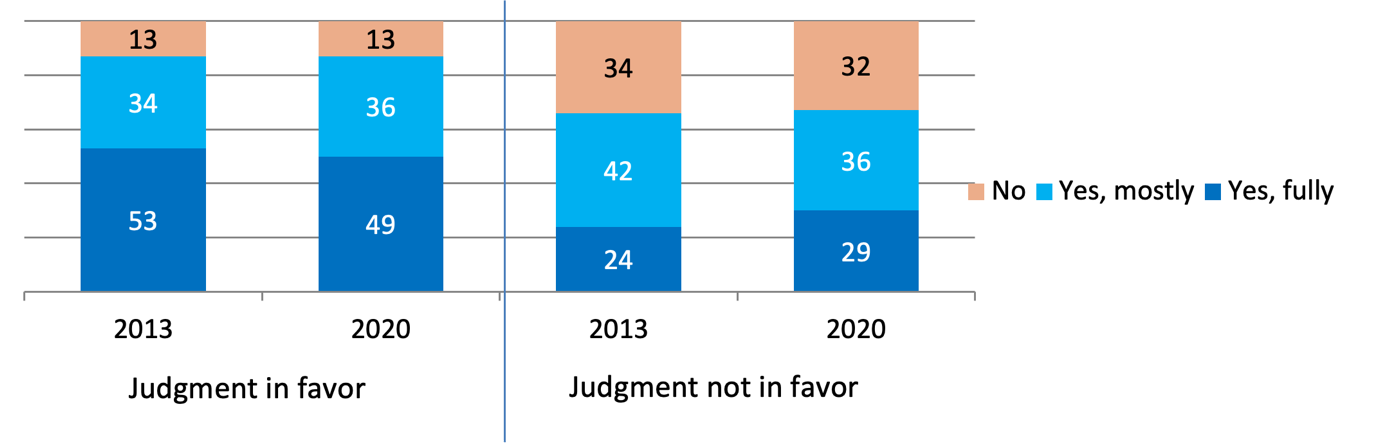

- While one might expect the evaluations of fairness by

court users to be influenced by the judgments in their cases. The majority of surveyed

court users who had unfavorable judgments still evaluated the trial as

fair. Approximately 30 percent of them even evaluated their

trials as fully fair (see Figure 131).

Figure 131: Perception of Fairness vs. Outcome of Judgment 2013 and

2020

- Perceptions of fairness of the justice system have

declined somewhat among the public and businesses since 2013, as shown

in Figure 132. The majority of all groups surveyed expressed

more positive than negative perceptions in 2013 compared to 2009.

However, even though at least 50 percent of groups (except for members

of the public with court experience) still rank the system as fair in

2020, the percentages of the groups finding it to be fair are lower in

2020 than they were in 2013.

Figure 132: Public Perception of Fairness of the Justice System,

2009, 2013 and 2020

- A majority of court users considered the system to be

fair or mostly fair without regard for the outcome of their case, with

criminal defendants the least likely to consider the system fair at

all. The perceptions of fairness dropped among court users in

civil and criminal cases in 2020 compared to 2013, even as the

perceptions of fairness by court users in misdemeanor cases slightly

improved. (See Figure 133.)

Figure 133: Court User’s Evaluation of Fair Trial, Notwithstanding

the Outcome of their Case, 2009, 2013 and 2020

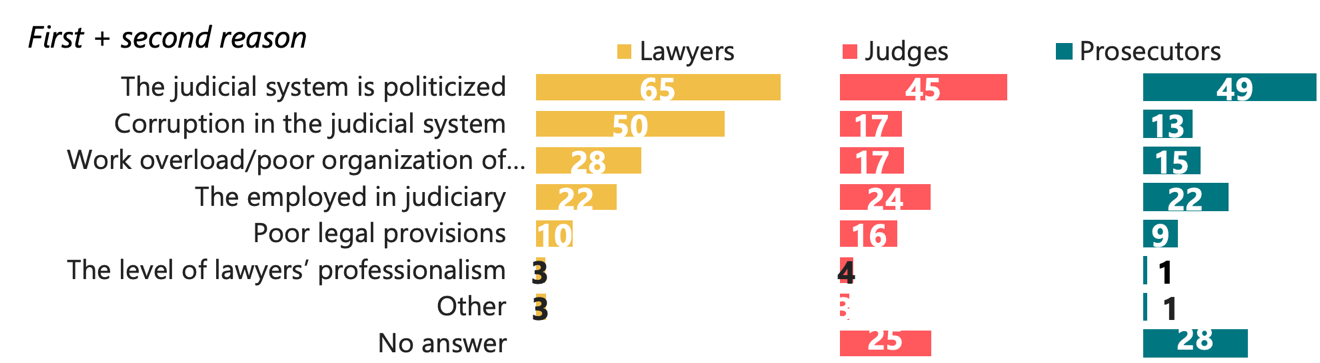

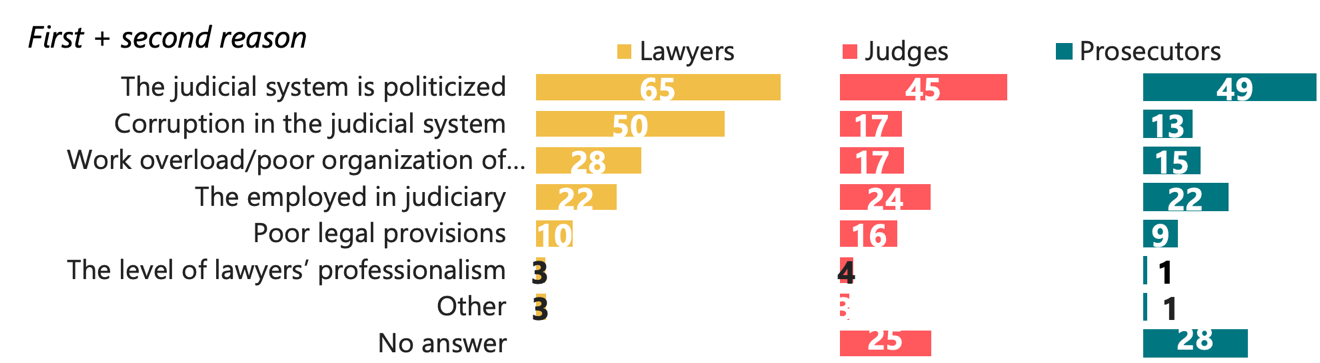

- The politicization of the judicial system and corruption

in the judicial system were reported as the most common causes of

unequal treatment by the system. The majority of judges,

prosecutors, and lawyers agree that the primary reason for unequal

treatment lies with politicization, while lawyers believe corruption

plays a much greater part than judges and prosecutors do. Lawyers also

found work overload/ poor organization as reasons for unequal treatment

more often than judges and prosecutors, as shown by Figure 134.

Figure 134: Reasons for Unequal Treatment Cited by Judges,

Prosecutors and Lawyers, 2020

- The quality of Serbia’s laws is also perceived to be part

of the unequal treatment. Sixteen percent of judges, nine

percent of prosecutors, and 10 percent of lawyers named poor legal

provisions as a source of unequal treatment.

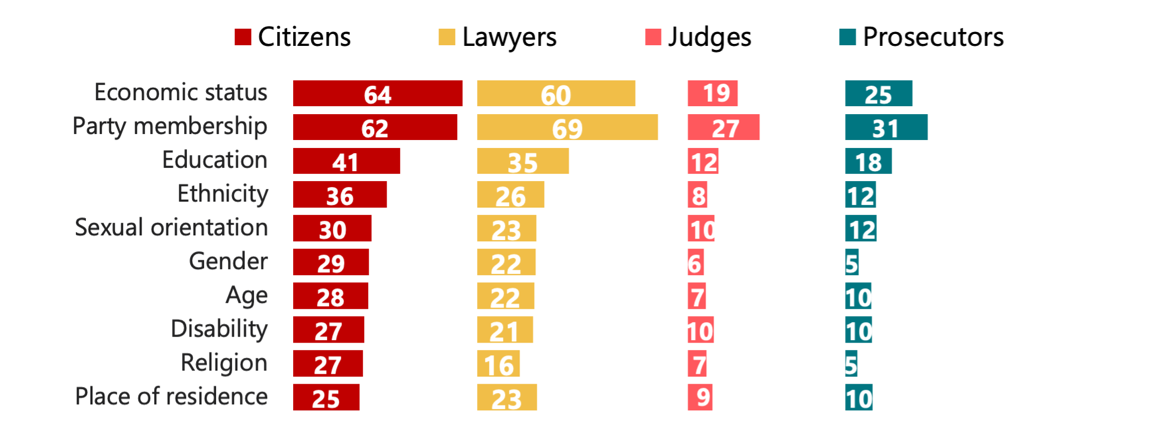

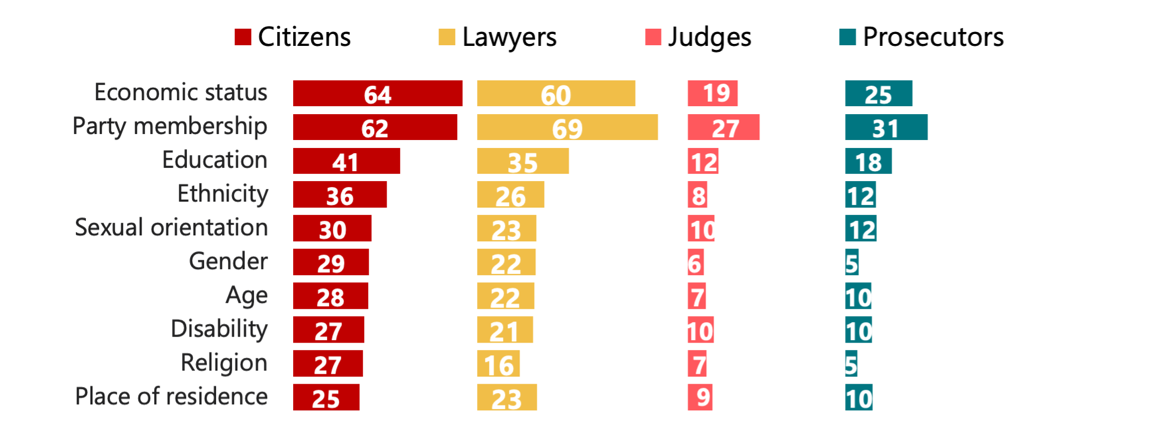

- Economic status was still cited as another primary reason

for unfair treatment. Twenty-five percent of prosecutors, 19

percent of judges, and 60 percent of lawyers, reported that the public

is treated unequally by virtue of their economic status, while 64

percent of citizens reached the same conclusion.

Figure 135: Equal treatment of citizens, 2020

Recommendations and Next

Steps ↩︎

The most fundamental change needed to promote integrity in the

judiciary is to reduce openings for political influence on judicial

operations. This can be accomplished by the National Assembly passing

legislation in line with the 2022 Constitutional amendments affecting

the membership and duties of the HJC and SPC. New laws should elaborate

new Constitutional provisions that remove the Assembly’s approval of

judicial appointments, as discussed in the Governance chapter.

Recommendation 1: Put in place an effective coordination

mechanism among institutions for the prevention of

corruption.

- Increase cooperation and coordination among the institutions with

responsibility for building the integrity of Serbia’s judiciary. (MOJ,

HJJ, SPC, SCC, RPP – short-term)

- Increase interaction between the Councils and the Agency for

Prevention of Corruption (APC) about the development and implementation

of integrity plans, rules, and standards governing conflicts of interest

and implementation of these regulations. (HJC, SPC, ACC –

short-term)

- Institute procedures for the central tracking of the source,

basis, and disposition of written complaints about courts and

prosecutors. (HJC, SPC, ACC – short-term)

- Develop procedures to ensure that the courts or PPOs to which

complaints are originally made report on the complaints and outcomes to

the APC and the Councils. (HJC, SPC, SCC, RPP – short-term)

- Amend the Law on Judges to be explicit about the disciplinary

accountability of court presidents. (MOJ, Parliament –

short-term)

- Analyze the outcomes of complaints at a systemic level; use this

data to inform future reforms. (HJC, SPC – medium-term)

- Address the continued designation of the Councils as the

second-instance disciplinary bodies. (MOJ, Parliament –

medium-term)

- Amend the disciplinary rules for both judges and prosecutors in

line with EU standards, so only serious misconduct and not mere

incompetence give rise to disciplinary proceedings. (MOJ, Parliament–

medium-term)

- Ensure adequate staffing of disciplinary departments in the HJC

and SPC. (HJC, SPC – medium-term)

Recommendation 2: Strengthen the effectiveness of the

Commissioner for Autonomy.

- Ensure that post is not vacant for a long period. (SPC –

short-term)

- Ensure resources for conducting work of the Commissioner. (SPC –

short-term)

- Publicize opinions and assessments of cases on the SPC website to

increase the transparency of the Commissioner’s work, inform the general

public and guide the conduct of public prosecutors. (SPC –

short-term)

Recommendation 3: Complete the development of procedures for

reporting by court presidents on instances when the random assignment of

cases was overruled and for monitoring these reports by the

SCC.

- Clarify the criteria for court presidents to assign or transfer a

case to a particular judge. (HJC, SCC – short-term)

- Adopt an automated mechanism for the random assignment of cases

in PPOs. (SPC, RPPO – medium- term)

Recommendation 4: Complete the process of adopting integrity

plans in all courts and PPOs.

- Require institutions to post Integrity plans on their

institution’s web page. (All – short-term)

- Provide mechanisms beyond developing a model plan on paper for

courts and prosecutors to identify integrity risks. (HJC, SPC, SCC, RPO

– short-term)

- Require each court or PPO to appoint senior personnel to monitor

the implementation of integrity plans. (HJC, SPC – medium-term)

- Ensure coordination and monitoring of implementation at the

central level. (SCC, HJC, SPC, RPPO – short-term)

Recommendation 5: Further implement the Law on

Whistleblowers.

- Ensure that all court and PPO employees know about protection for

whistleblowers through enhanced general training. (HJC, SPC, JTC –

short-term)

- Provide training to the whistleblower point person in each

institution. (HJC, SPC, JA – short-term)

- Create an environment for safe and effective reporting of all

types of undue influence. (HJC, SPC – medium-term)

Recommendation 6: Complete the process of ensuring that all

court and PPO employees, and the public, know about rules related to

conflicts of interest.

- Clarify criteria to determine whether a gift was “in connection

to the discharge of public office.” (HJC, SPC – short-term)

- Ensure the collection, maintenance, and accessibility of the

records required by Article 41 of the Law on the Anti-Corruption Agency,

requiring that judicial officials report on gifts. (HJC, SPC, SCC, RPPO

– short-term)

- Develop public information regarding the law and policy on giving

gifts to court and PPO employees, and make it available on websites and

in brochures available at the courts and PPOs. (HJC, SPC, SCC, RPPO –

medium-term)

Recommendation 7: Fully implement the Code of Ethics and

Rules of Procedure of the Ethical Board of the HJC.

- Provide written guidance on ethical issues with practical

examples and recommendations, including online FAQs. (HJC –

short-term)

- Make existing training mandatory for all judges and prosecutors.

(HJC, SPC, JA – short-term)

- Monitor the impact of confidential advice/counseling on

appropriate conduct in particular cases. (HJC, SP– medium-term)

- Expand the Ethical Code of Prosecutors to include a level of

detail similar to the code for judges regarding

permissible/impermissible conduct. (SPC – short-term)

Recommendation 8: Enforce rules about the appointment,

disqualification, and compensation of expert witnesses.

- Ensure that all expert witnesses are compensated at the same rate

in accordance with the Rulebook on Reimbursement of Expert Witnesses.

(MOJ, SCC – short-term)