Financial Resources

Management

- Financial management has a significant impact on both the

efficiency and quality of delivering justice as well as on other

auxiliary functions of the judicial system (i.e. HR, ICT,

infrastructure). Efficient organization of financial management

and optimal allocation of financial resources are vital for effective

service delivery in all segments of the system.

Main findings ↩︎

- Financial management has a significant impact on both the

efficiency and quality of delivering justice as well as on other

auxiliary functions of the judicial system (i.e., human resources, ICT,

infrastructure). Efficient organization of financial management

and optimal allocation of financial resources are vital for effective

service delivery in all segments of the system.

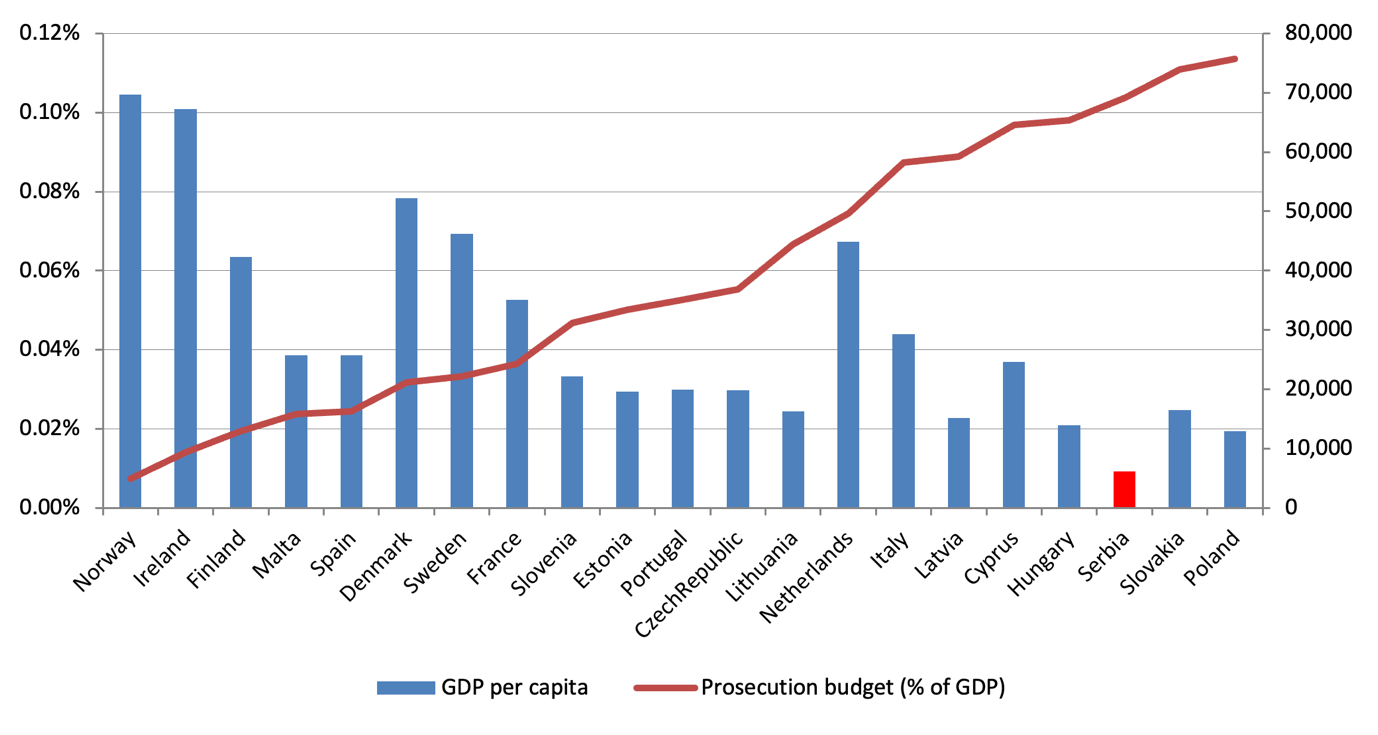

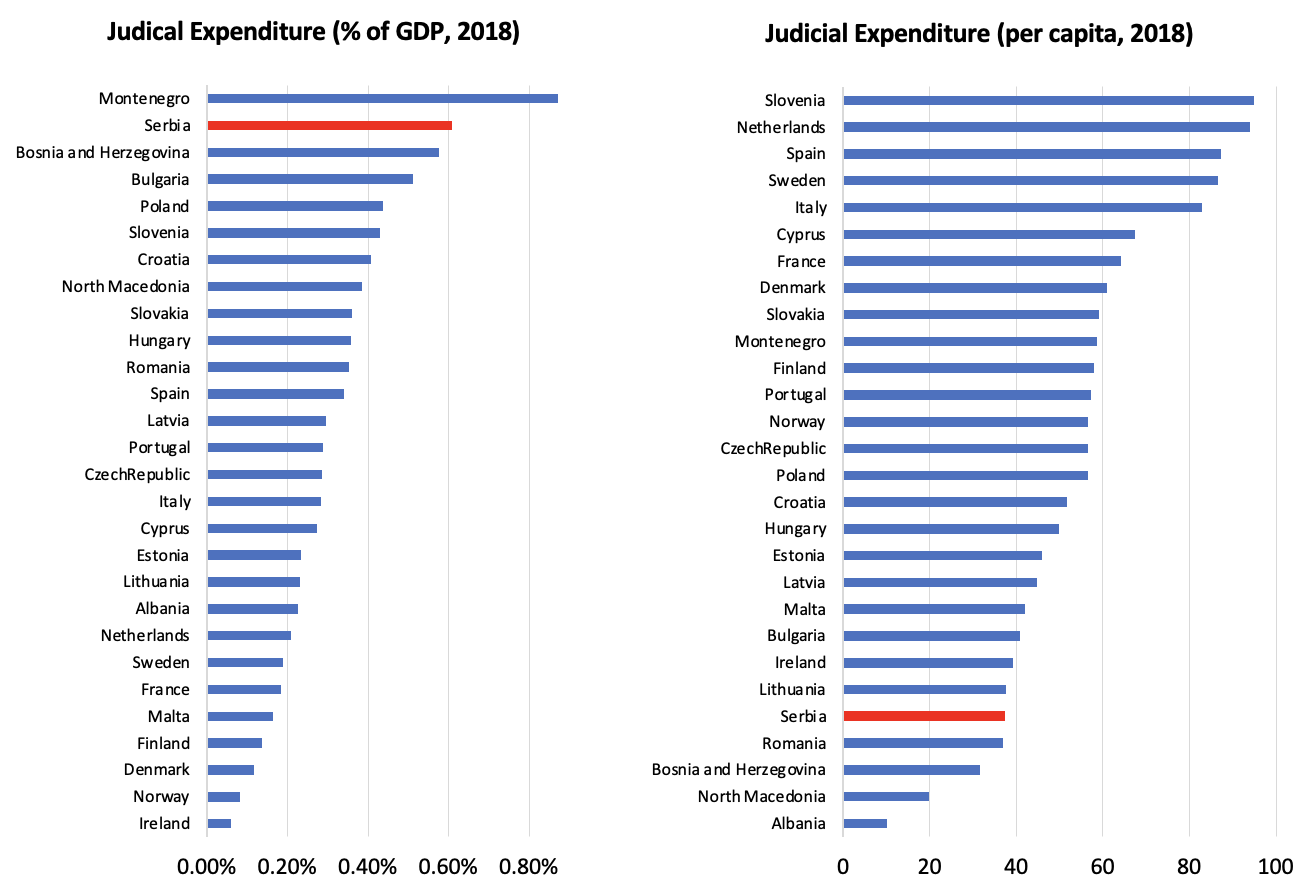

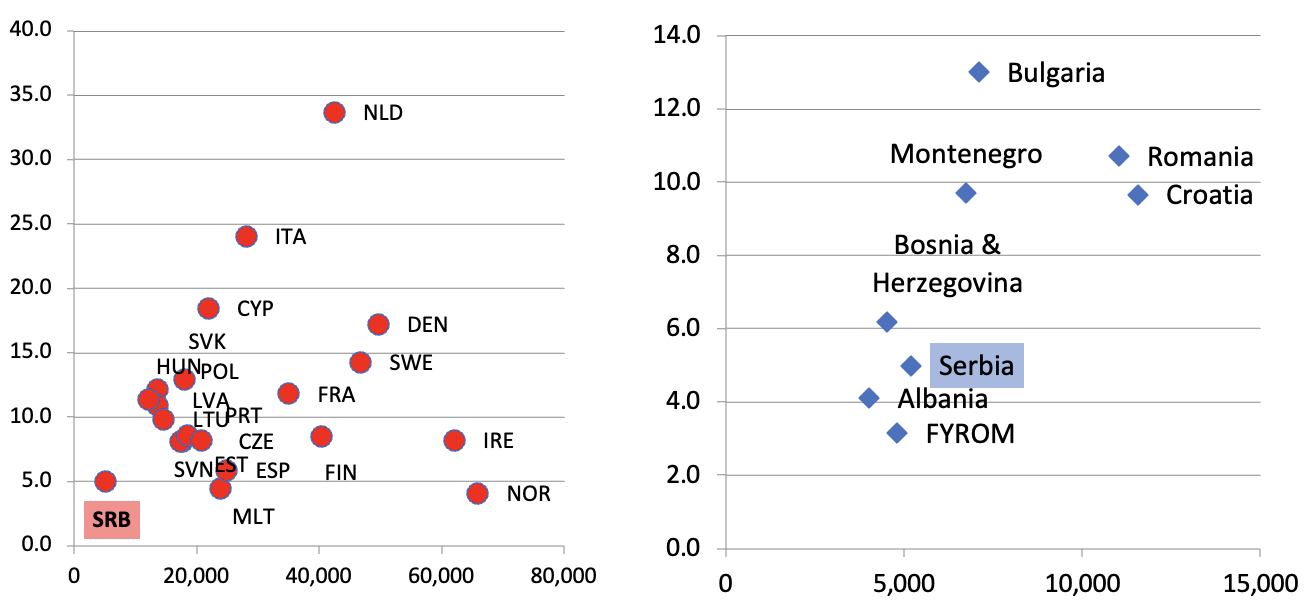

- Compared to other European countries, Serbia’s judicial

system is funded at moderate levels. Serbia’s judicial budget as a

percentage of GDP was near the top of its peer countries, while its

judicial expenditure per capita is among the lowest in Europe (i.e., EUR

29.1 per capita). When these two dimensions are combined,

Serbia’s judicial system could be described as operating at affordable,

although relatively low levels compared to other European countries.

This held true for both of its main components – the court and

prosecution systems.

- The budgetary system of the Serbian judiciary remains

unnecessarily complex and fragmented and hampers the development of

rules and guidelines for financial management in the judiciary.

As in 2014, the formulation, execution, and reporting of different

portions of the judicial budget remain split by the Budget System Law

between the MOJ and the HJC/SPC. As a result, there is a lack of

accountability for overall judicial budget performance, and no central

data is available to allow consistent, ongoing evaluation of financial

management.

- In 2016 judicial institutions were granted access to the

budget execution system. This allowed real-time tracking of

their annual expenditure and increased transparency of their financial

operations. This was necessary but, in the end, an insufficient step

towards achieving judicial institutions’ budgetary independence.

Judicial institutions’ individual accounts within Treasury were closed,

and their budgets started being executed from the central budget

execution account. These changes did not earn budgetary independence for

judicial system institutions. Instead, in practice, the MOJ and HJC/SPC

retained full control of the budgets of judicial institutions by simply

replacing the management of transfer requests for budget appropriations

management. The issue of lack of flexibility in budget reallocation

seems to have been magnified by the recent changes.

- Budgeting processes are not linked to performance

criteria. Annual budgets are prepared by making minor upward

adjustments to the prior year’s budget or spending. The entire budget

process of the country relied on limits set by the MOF, and judicial

authorities could not provide evidence-based rationales for challenging

the MOF limits.

- Budget formulation practices have not progressed much

since 2014. With the exception of the courts, there is no

budget preparation software linking the direct or indirect budget

beneficiaries. Budget preparation and monitoring in the MOJ and SPC is

done through an Excel spreadsheet exchange, while since 2017 HJC is

using a BPMIS tool that is poorly maintained, inflexible, and

incompatible with the BPMIS used by the MOF to prepare the state budget

(software collecting budget requests from DBBs).

- Existing automated case management systems do not allow

courts or PPOs to determine their per-case costs, perform full-scale

program budgeting or reduce their arrears and the penalties assessed

through enforced collections. There is not enough automatic

exchange of data between the various information systems used within the

judicial system for any of these functions to

occur. As in 2014, interoperability between the existing systems remains

an issue to be addressed in the future.

- Budget preparation software used in courts allows for

manual case-related data entry, but this feature is not sufficiently

exploited. The exchange between other systems is at low levels.

Since 2014, there have been attempts to link the accounting software

(ZUP) with budget execution by allowing the external formulation of

payment requests based on accounting records. However, the use of this

feature is not very widespread.

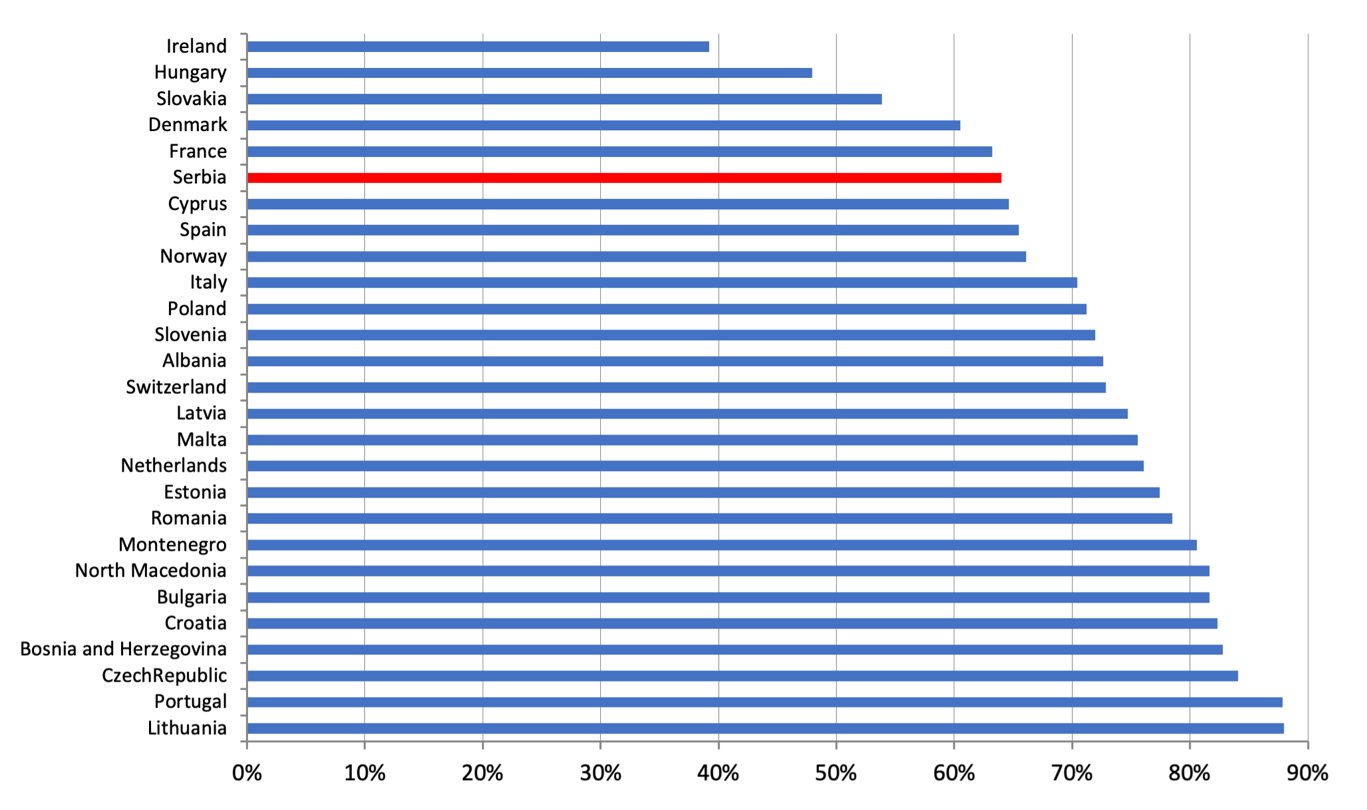

- When compared to other European court systems, Serbia’s

share of wage-related expenses lies well below the median (approximately

69 percent compared to 74 percent). However, as the amount of

funds spent for other purposes is insufficient overall, judging wage

expenses as a ratio of total expenditures does not provide a complete

picture. The decrease in the share of wages seen in the period from 2014

onwards is a consequence of the overall increase in capital expenditures

on one side and the drop in the overall public sector wage bill in

2015.

- Capital expenditures increased over the past four years

to fund needed, accelerated implementation of large judicial

infrastructure investment projects managed by the MOJ. The

share of CAPEX in total expenditure went from an average of 2.3 percent

over the 2010-2013 period to more than 8 percent in 2019. The increase

in capital expenditure matches the trend of increasing funds from

international loans and donations, which are at the disposal of the

judiciary for infrastructural investments. Internal capacities for

capital project implementation have to be further developed to ensure

the sustainability of the share of CAPEX in total expenditure. However,

more needs to be done to resolve the issue of the lack of procedures for

the selection and prioritization of public investments.

- As a result of the introduction of private notaries and

enforcement agents, court fees have dropped more than 40 percent over

the past years. Likewise, the share of the judicial budget

financed from court fees has dropped significantly compared to the

previous period from almost 50 percent to an average of 20 percent of

the court system budget. In absolute terms, this is commensurate with

the decline in court fees. Instead, these fees are distributed to the

general budget. The rate of decrease stabilized in the past couple of

years, and court fees are not expected to decline further, at least not

significantly.

- There was no significant progress made in terms of

recording and collecting debts related to court fees. The

introduction of Tax Stamps facilitated court fees settlement, but the

issue of uncollectable court fees persists. Although the level of

uncollectable court fees cannot be precisely determined due to a lack of

accurate records, some estimates are that between 30 and 40 percent of

those remain unpaid. The issue is slightly alleviated

by the fact that a certain share of court fees (i.e., mostly for

enforcement cases) is now collected through enforcement agents on behalf

of courts.

- There were large variations in costs per active case

across the judicial system and within the courts and PPOs of the same

level. As noted above, the lack of interoperability between CMS

and budget execution systems prevented detailed tracking of expenses per

case. To a significant extent, the variations were due to disparate

views of which criminal investigation costs should be paid by courts and

which should be paid by PPOs. This issue relates to ongoing weaknesses

identified in the budget formulation process in the 2014 Functional

Review and the lack of communication between CMS and the financial

software components across the judicial system.

- Compared to the levels observed at the end of the period

covered by the 2014 Functional review (i.e., at the end of 2013), the

level of arrears dropped significantly. In the case of courts,

arrears dropped from nearly 15 percent of total expenditures at the end

of the first quarter in 2014 to just above one percent at the end of

2019. As correctly predicted by the previous Functional Review, one

important difference is that the transfer of responsibility for criminal

investigation management brought arrears into the prosecutorial

system.

- Ongoing arrears hamper the effective management of

current year resources. Even at the lower levels now being

experienced, significant effort should be put into properly addressing

the source of arrears accumulation – both in courts and PPOs.

Budgetary Framework

of the Judicial System ↩︎

- The Budget System Law (BSL)

is the cornerstone legislation that governs all aspects of

judiciary financial management in Serbia – from budgeting to accounting

and financial reporting. It defines the scope of the budget,

structure, and management of the Treasury Single Account (TSA) and the

general ledger, budget calendar and elements of financial plans of

budget beneficiaries, the process of budget execution and accounting,

and the reporting framework. It differentiates between direct and

indirect budget beneficiaries: direct budget beneficiaries are defined

as “the institutions and organizations established by the state” (e.g.,

ministries and separate administrations at their arm’s length, such as

the Supreme Court of Cassation and specialized appellate courts), while

indirect budget beneficiaries comprise most judicial and educational

institutions. The Rulebook on Budget Execution defines the detailed

procedures for financial planning and execution of public institutions’

budgets, which vary depending on an institution’s status as a direct or

indirect budget beneficiary.

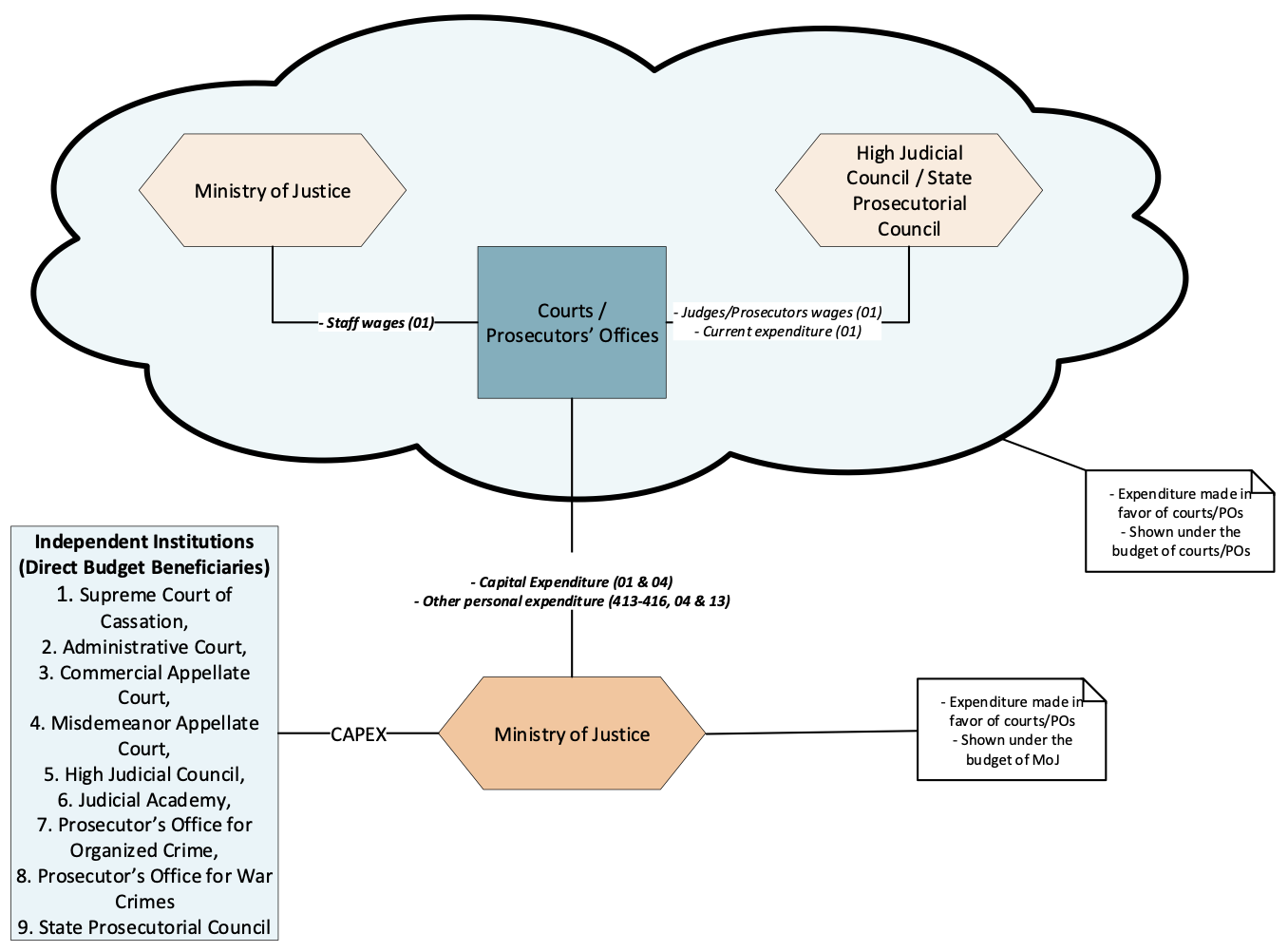

- The MOJ, together with the HJC for the courts and the SPC

for the PPOs, manages the budgets of the judicial system. The

competencies of the HJC, SPC, and MoJ over the budgets of judicial

institutions overlap and include harmonizing budget formulation and

monitoring budget execution, and collecting and aggregating annual

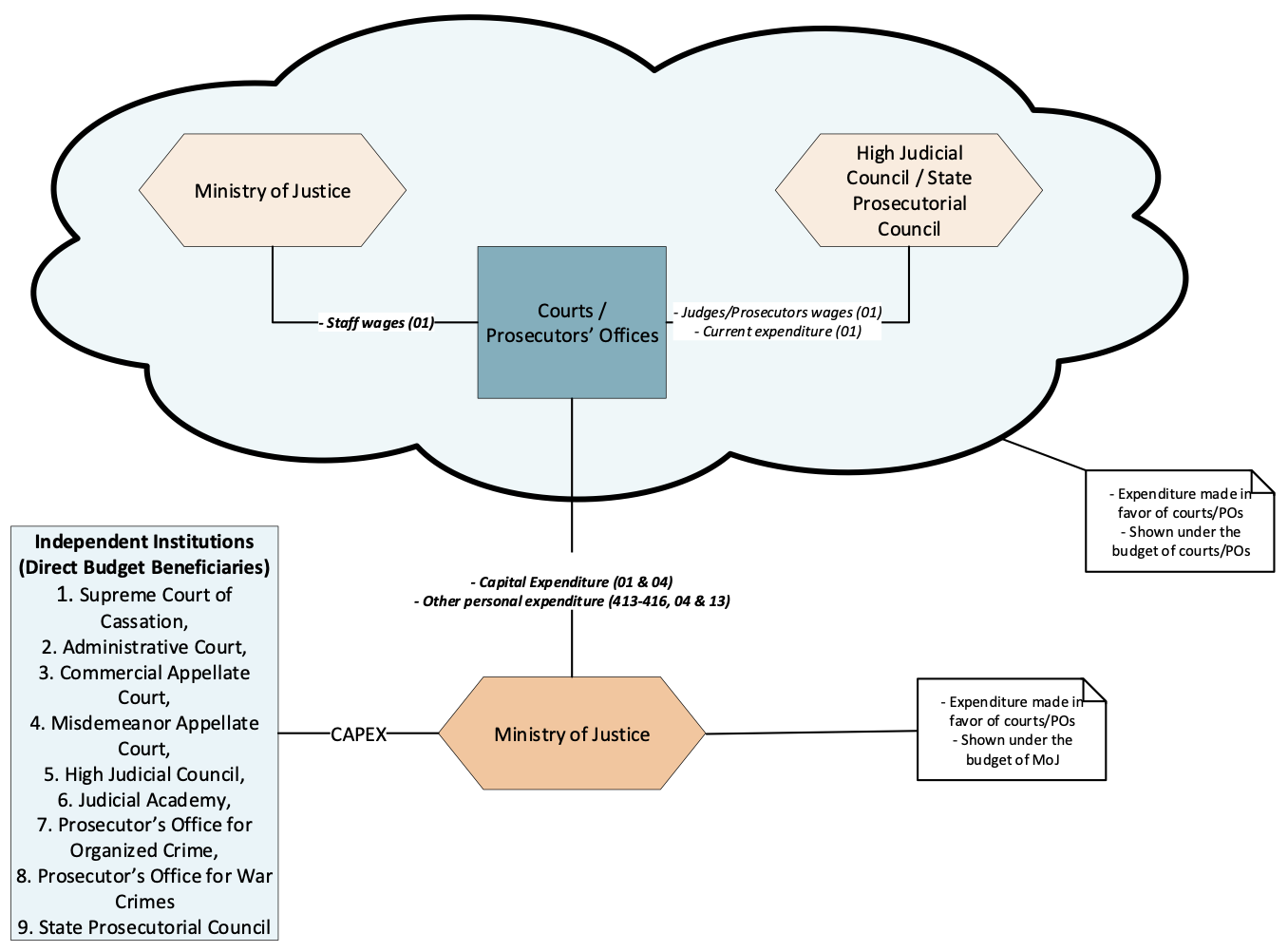

financial statements. Figure 142 below depicts the overlapping structure

of the budgetary framework and contains the types and sources of

expenditure managed by HJC/SPC and MoJ.

Figure 143: Budgetary Framework of Serbia’s Judicial System

- The HJC, the SPC, some courts and PPOs, and the Judicial

Academy are financially independent of the HJC, SPC, and the MOJ since

they are DBBs and are provided with flexibility and independence in

executing their budgets. The relevant courts and PPOs have

specialized rather than general jurisdiction, i.e., the Supreme Court of

Cassation, Administrative Court, Commercial Appellate Court, Misdemeanor

Appellate Court, Prosecutor’s Office for Organized Crime, and the

Prosecutor’s Office for War Crimes. Their budget preparation process is

done in direct communication with the MoF. Also, they are free to

utilize their annual operating appropriations to the full extent, as

defined by the annual Budget Law.

- The type of expenditure dictates whether the MOJ or the

HJC/SPC manages a particular budget function for an indirect budget

beneficiary. The Councils manage budget

functions for i) wages and wage-related expenses of judges/prosecutors; ii) material costs (e.g., rent,

utilities, gas, office materials, postal services); iii) travel

expenses; iv) certain contract services (e.g., mandatory representation

and expert witness services); v) current maintenance (e.g., painting and

decoration, plumber services, repair of vehicles, computer equipment,

furniture), and vi) fines and penalties. On the other hand, the MoJ

manages the budget for wages and wage-related expenses of non-judicial

and non-prosecutorial staff, as well as capital expenditures.

- Starting in the fiscal year 2016, courts and PPOs became

the first indirect budget beneficiaries (IBBs) to be included in the

budget execution platform (ISIB), which, until that

point, had been reserved for direct budget beneficiaries (DBBs)

only. Before that, almost all judicial system institutions were

IBBs, meaning they had to rely on physical transfers of funds from their

superior DBB – HJC/SPC and MoJ to finance their operations. These

transfers were made to the sub-accounts of each institution held at the

Treasury Administration, which had a web-based application to facilitate

the execution of payment orders. The web application was used by the

majority of judicial institutions, but others were forced to place their

payment orders through the nearest Treasury branch office. Budget

preparation was done through the councils and the MoJ, which collected

financial plans (draft budgets) from courts, aggregated them, and

adjusted them to fit expenditure ceilings set by MoF. Reporting from the

accounting records held by each individual judicial institution was done

directly only at the end of fiscal years to each of the superior DBBs

rather than throughout the year, limiting institutions’ ability (and

incentive) to manage resources proactively. It was only through an

ex-post audit that the reliability of their expenditure records could be

determined, and mid-year adjustments based on expenditure patterns

(whether up or down) were infeasible, reducing budgetary

responsiveness.

- The use of the common budget execution platform after

2016 has not effectively added to the budgetary independence or

responsiveness of judicial institutions. The budget

appropriations of individual courts and PPOs are still decided from the

central level (i.e., SPC/HJC and MoJ) at a detailed level in the budget,

and in-year appropriation changes have to be approved centrally as well.

The appropriation distribution among courts and PPOs are made based on

their expressed and determined needs during the budgetary process.

Procedures for altering appropriations are complex, rigid, and

controlled closely by MoF. SPC/HJC and MoJ indicate that this is why

they retain certain shares of the total appropriation to these

institutions as undistributed. As a practical matter, this allows MoJ

and the councils to increase an institution’s appropriation when

necessary, but it does not add to the strategic efforts of Serbia to

secure budgetary independence or responsiveness of the judicial system.

However, a significant benefit of moving judicial institutions under the

umbrella of ISIB has been that expenditure control mechanisms can now be

applied before charges are incurred, rather than waiting for a post-doc

audit of expenditures. Reporting practices also have not changed since

judicial institutions still compile financial reports based on their own

records and send them to SPC/HJC and MoJ, which compile and forward them

to the Treasury.

- In 2015, modifications of the BSL allowed the

introduction of program budgeting across Serbia’s budgetary system, but

there was little progress towards the full implementation of program

budgeting, and this is true for the Serbian budgetary system as a

whole. The BSL introduced many novelties, including changes in

the structure of the budget and the requirement for DBBs to assess the

performance of their programs. Unfortunately, in practice, this was not

done, so performance assessments did not form the basis for potential

adjustments to the financial plans of judicial institutions or the

cornerstones of their budget preparation process. Instead, budgets

continued to be prepared on an annual rolling basis, based to a great

extent on previous years’ budget execution data. The Councils simply

combined the budget requests from their courts and PPOs and adjusted

them to the overall limits set by MoF.

- Measuring budget performance is hindered by the lack of

integration and interoperability between the CMS and financial

management software, and other manual approaches to integrate financial

and performance data are not evident. There is no automatic

exchange of data between these systems since such functionality is not

developed in either system. There is no evidence of systematically

considering financial data in the context of case-related analytics – in

either the court or prosecutorial system.

- The current financing structure of Serbian courts is

unnecessarily complex, creating much additional workload and

confusion. Although the presentation of the

judicial system budget had been split into programs and projects since

2015, different segments of the budget still rested with different

institutions. For instance, the budget for Basic Courts is shown under

the budget chapter called “Courts”, and the heading “Basic Courts. This

heading contains two projects: implementation of court activities (for

which the budget is managed by HJC) and administrative support to the

work of Basic Courts (for which the budget is managed by MoJ). F managed

by MoJ includes only appropriations related to net wages and social

contributions of non-judicial staff. The rest of the budget, including

capital expenditures and other personnel expenses such as in-kind

compensation, employee social benefits, awards, bonuses, and other

special payments, for the activities of Basic Courts, is shown under the

budget of the MoJ. A very small share of material costs and current

maintenance also are financed by MoJ. While some specific capital

expenditure projects related to courts are shown explicitly in the MoJ

budget, the majority of appropriations for capital interventions made in

favor of courts are part of a general appropriation for capital

expenditure under MoJ’s budget and are not earmarked for the

courts.

- In addition to the division of authorities for different

aspects of the budget, both the MOJ and HJC portions of the budget are

financed from both budget revenues (i.e. source 01) and internal (‘own

source’) revenues coming from court fees (i.e., sources 04 and

13). MoJ also takes a certain portion

of the court fees to finance expenditures for court proceedings.

Simultaneously, capital expenditures are financed from general budget

revenues but also from internal funds. MoJ is financing capital

expenditures and non-wage-related personal expenses (i.e., in-kind

compensation, employee social benefits, awards, bonuses, and other

special payments) while they also cover a certain portion of current

maintenance. Apart from the organizational difficulties and natural lack

of coordination between the two budgets, such a system lacks clarity and

transparency. All of the MoJ administered appropriations – wages as well

as capital appropriations - are not shown under courts’ budgets but are,

instead, placed within the budget of MoJ, where no distinction is made

between courts and PPOs in terms of how much each of the judicial

sub-systems is receiving for these purposes.

- Budget preparation is carried out without a

well-developed budget preparation information system (BPMIS).

PPOs manually exchange MS Excel files through email, which represents a

serious workload issue and presents a high level of risk regarding the

integrity of data and general security. Courts have an information

system for budget preparation, but all courts do not use it, and it

lacks compatibility with the BPMIS used at the central government budget

level. The introduction of a well-planned BPMIS across the judicial

system should solve the operating shortcomings of current practices and

also free staff to build their skills for more effective budget

performance assessments; these skills would be particularly important as

Serbia deals with the challenges posed by EU accession

processes.

- Procurement of large capital investment projects which

are complex to process or envisage multi-year financial commitment are

centralized at the MoJ. Courts and PPOs perform

projects/purchases that are smaller in scale. MoJ indicates that

individual institutions lack the capacity to carry out complex

procurement procedures because they do not have staff dedicated

exclusively to procurement.

- Individual appropriations in the capital budget are set

differently than for operating funds. MoJ not only continues to

act on behalf of DBBs as well as IBBs for large capital, but budgetary

funds for these purposes are retained by MoJ. Based on the limits from

MoF and the aggregate needs for capital expenditures, the MoJ sets the

overall volume of funds earmarked for this purpose. While courts and

PPOs prepare their procurement plans, which MoJ approves, funds are not

allocated in separate appropriations for courts and PPOs but are part of

an overall capital expenditure appropriation under the MoJ’s budget

section. Courts and PPOs are then required to file a request to MoJ to

initiate the procurement procedure. After the official approval is

attained, the procurement starts, and finally, the goods/services are

paid at the end once the whole documentation reaches the MoJ and is

checked against the Procurement Law.

Budget Levels and Sources ↩︎

Expenditure Benchmarking ↩︎

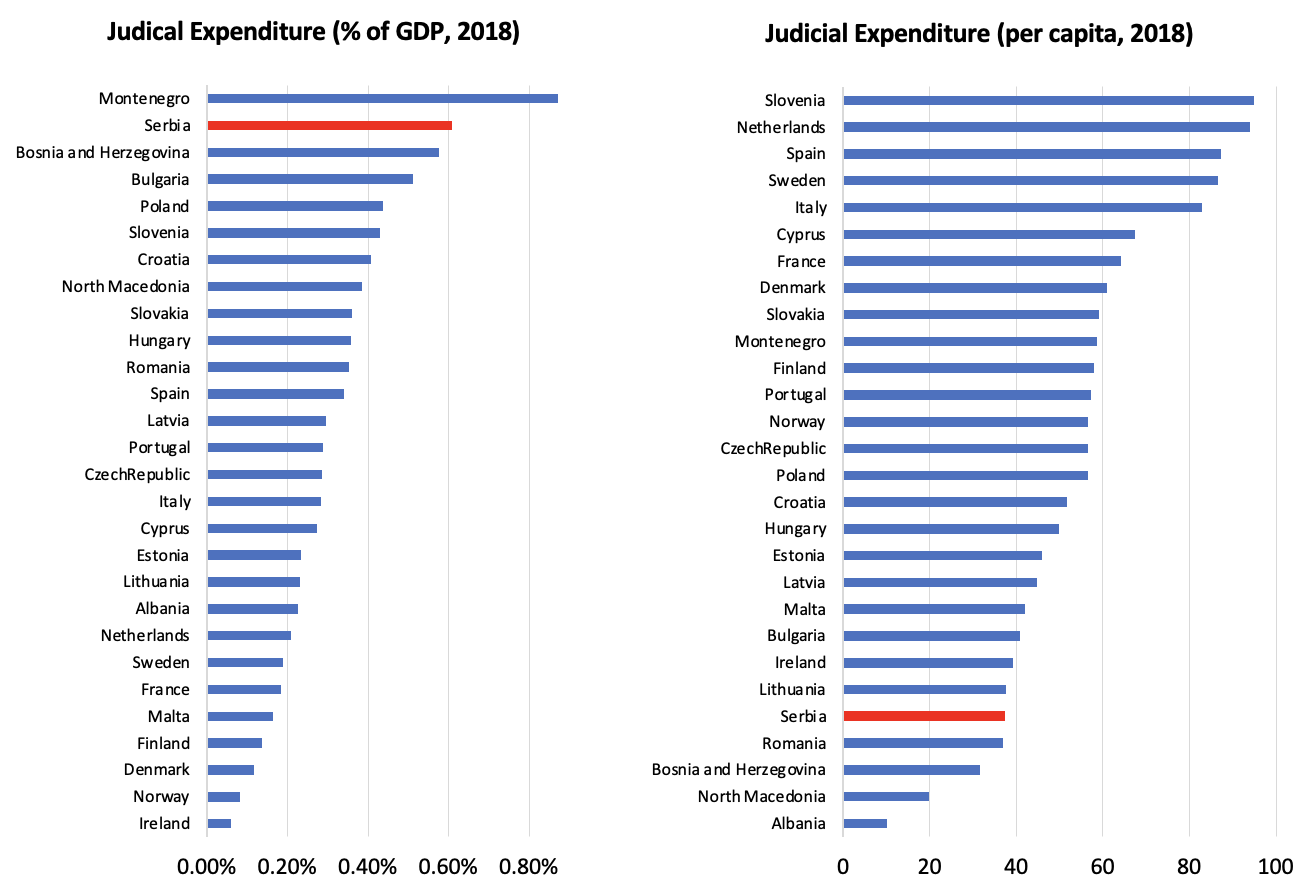

- Serbia ranked at the high end in Europe for overall

judicial system expenditure measured as a share of GDP in 2018. At the

same time, it lies well below the European average when judicial

expenditure was measured in per capita terms. In 2018,

according to the latest CEPEJ report on efficiency and quality of

justice, Serbia spent 0.61 percent of GDP

on its overall judicial system, while the European average was 0.33

percent (see Figure 143 below). At the

same time, per capita expenditure was EUR 37.4 which was well below the

European average of EUR 54.6. To expend the average per capita on the

Serbian judiciary, an additional 46 percent or RSD 14.8 billion would

need to be appropriated.

- The same trend was observed in other European countries

with comparable GDP levels. Most of these countries were

Serbia’s regional peers (e.g., Albania, Bosnia & Herzegovina,

Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro, Romania, and North Macedonia). Within

this group, the average expenditure stood at EUR 35.9 per capita and

0.49 percent of GDP, a bit lower than in Serbia.

Figure 144: Total judicial expenditure, 2018, Serbia and Europe; as

percent of GDP (left), per-capita (right)

Source: 2020 CEPEJ Report (2018 data) and authors’

calculations

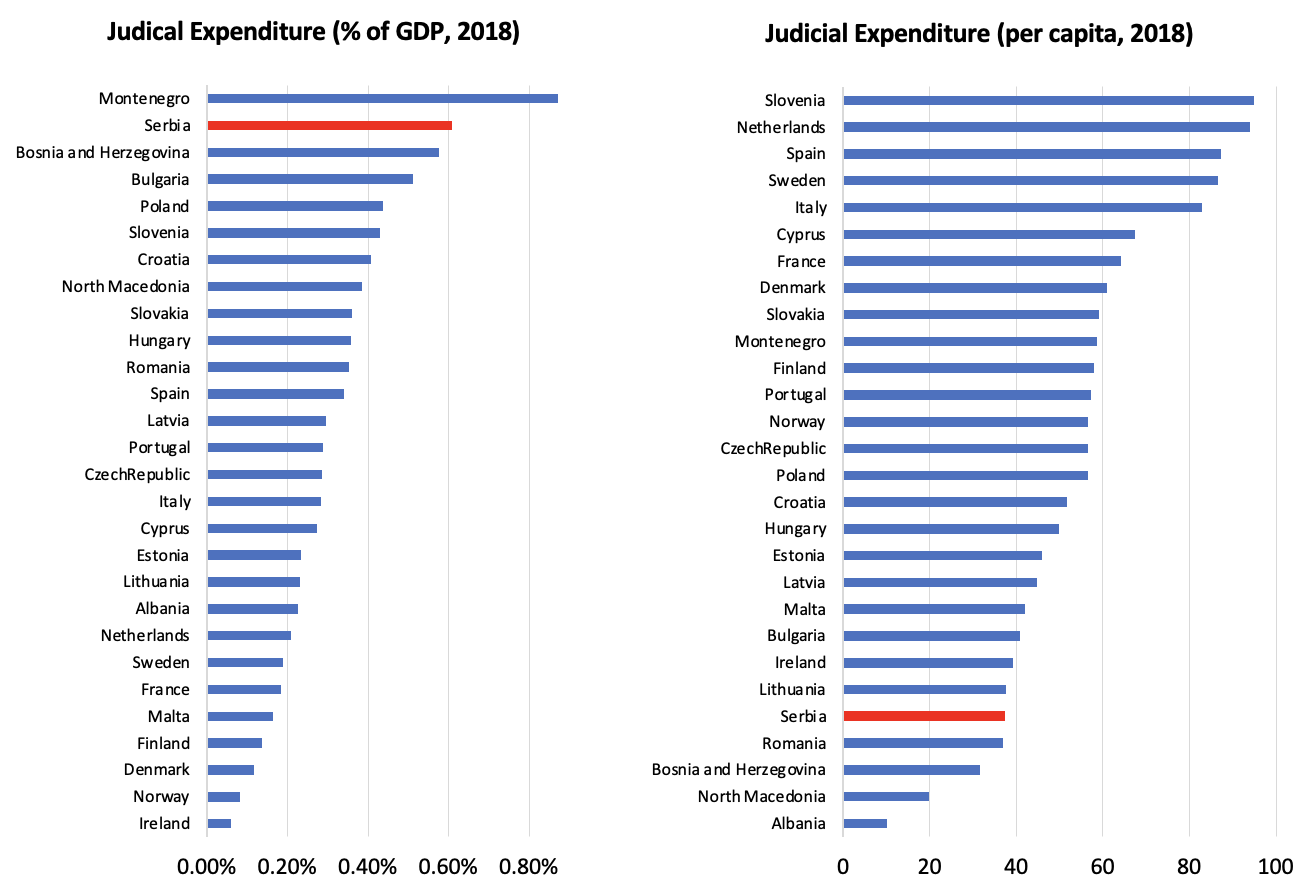

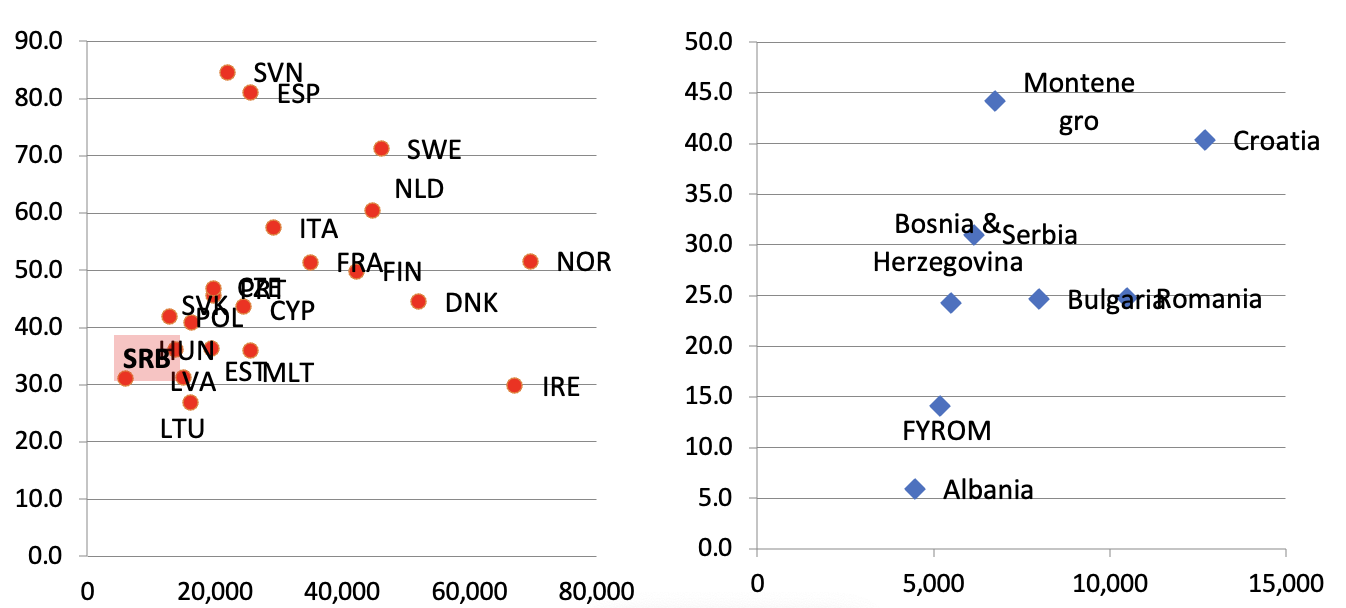

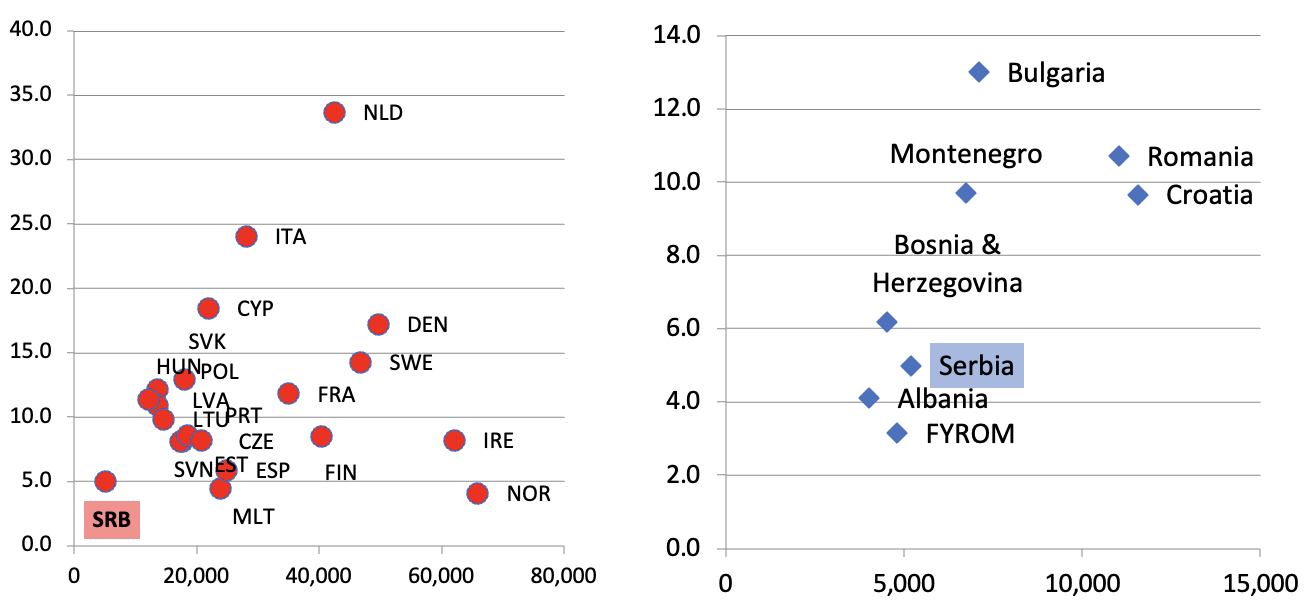

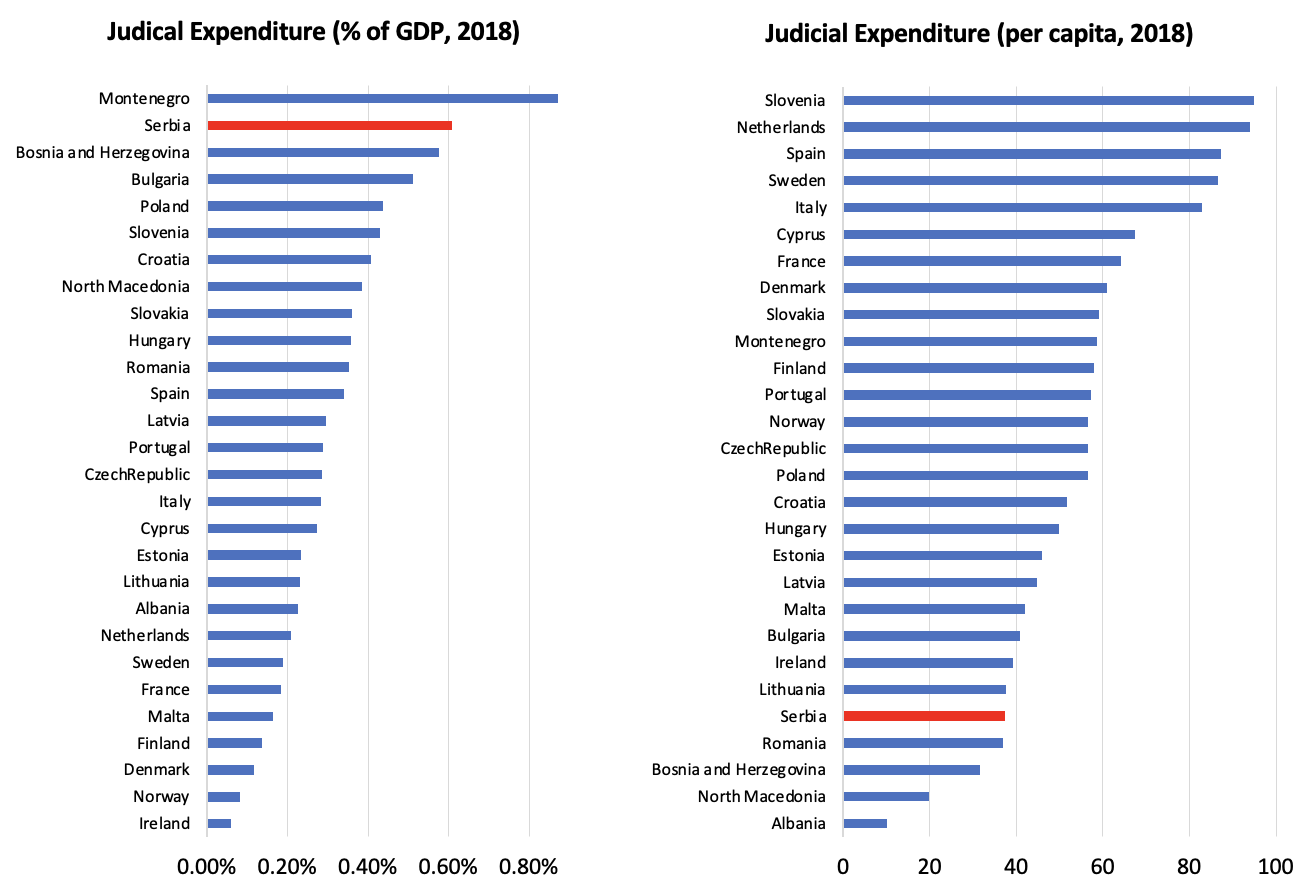

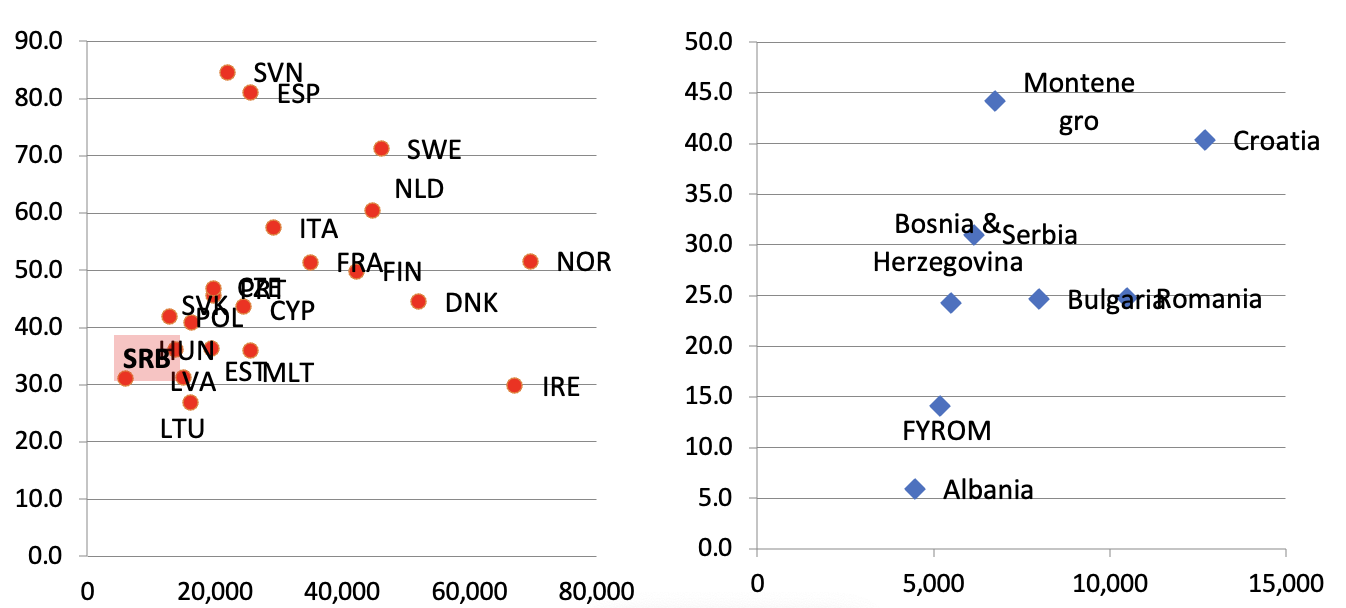

- The expenditure level per capita raises a question of

financial sustainability. Serbia is, together with Ireland, the

European country which spends the least on its court system in per

capita terms. Total court expenditure was 0.50 percent

of GDP. Excluding countries from the region mentioned above, the only

country with somewhat comparable levels of expenditure was Slovenia,

with 0.38 percent of GDP (see Figure 144 below). At the same time,

Slovenia is the country with the highest per capita court expenditure

with EUR 84.5, while the average lies at EUR 47.5. Figure 144 below

indicates that Serbia would have to adjust its court system expenditure

downwards significantly to align it with its GDP per capita

level.

Figure 145: Court expenditure as percent of GDP in the context of GDP

per capita, 2018, Serbia and EU

Source: 2020 CEPEJ and WB calculations

- Compared to the court system expenditures of its regional

peers, Serbia is in the mid-range of financial sustainability.

The average regional GDP per capita in 2018 was EUR 7,400, while the per

capita court expenditure was EUR 26.1. With the GDP per capita being

close to the average (i.e. EUR 5,191), Serbia was roughly aligned with

the average regional spending. The only countries which obviously were

out of the average were Montenegro, which had very high per capita

expenditure levels (i.e. EUR 44.2), and Albania, which seems to be

underspending per capita (i.e. EUR 5.9); Croatia spends almost twice as

much as Romania (i.e. EUR 40.3 versus 24) with almost identical GDP per

capita.

Figure 146: Court expenditure per capita in the context of GDP per

capita, 2018; Serbia and EU (left), Serbia and regional peers

(right)

Source: 2020 CEPEJ and WB calculations

Figure 147: Prosecution expenditure as percent of GDP in the context

of GDP per capita, 2018, Serbia and EU

Source: 2020 CEPEJ and WB calculations

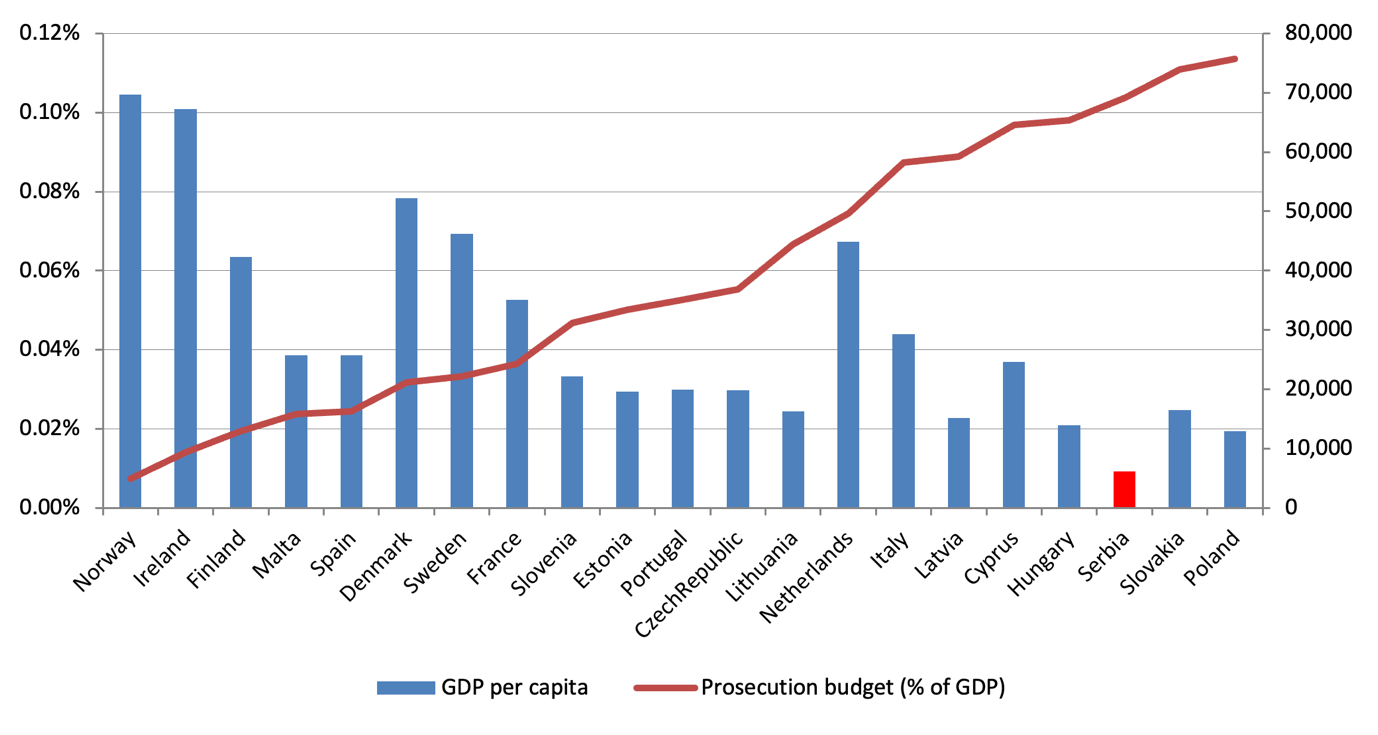

- Likewise, with EUR 5 per capita, Serbia’s prosecution

system expenditures were at the very bottom when compared with EU

countries, while it ranked among the top spenders when expenditure is

scaled with GDP. Compared to regional countries, Serbia’s

prosecution expenditure was at the average and roughly aligned with its

wealth level.

Figure 148: Prosecution expenditure per capita in the context of GDP

per capita, 2018; Serbia and EU (left), Serbia and regional peers

(right)

Source: 2020 CEPEJ and WB calculations

Budget Execution, Trends,

and Sources ↩︎

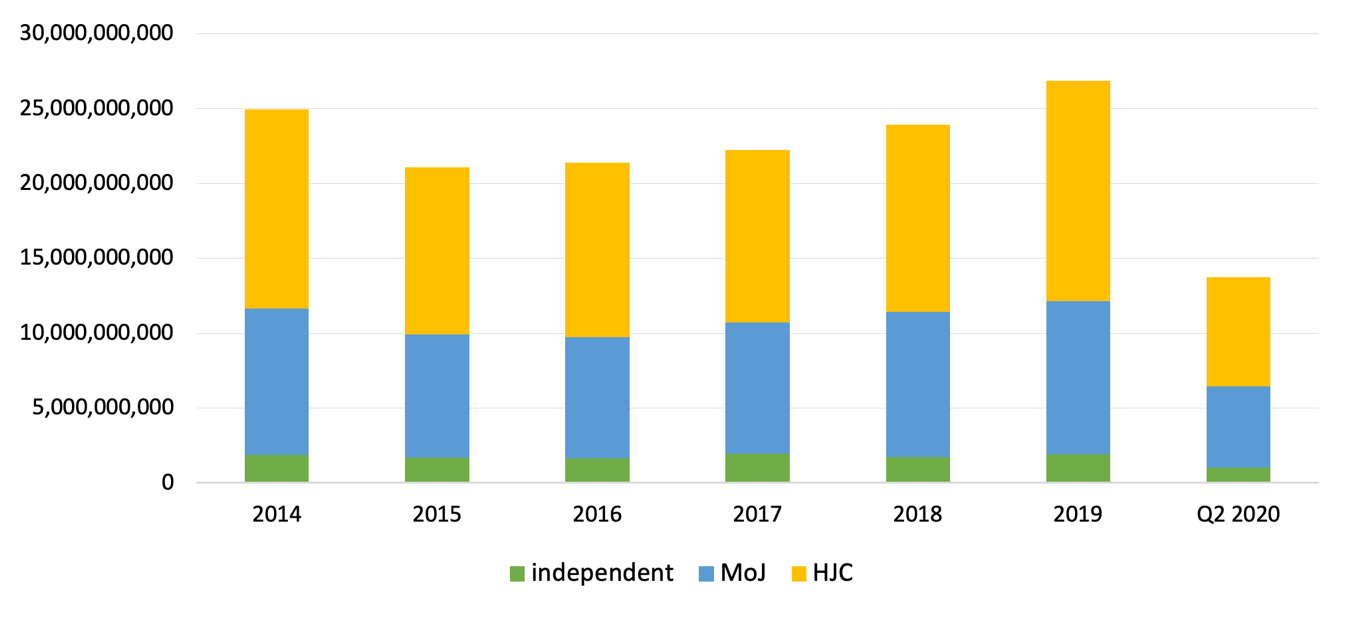

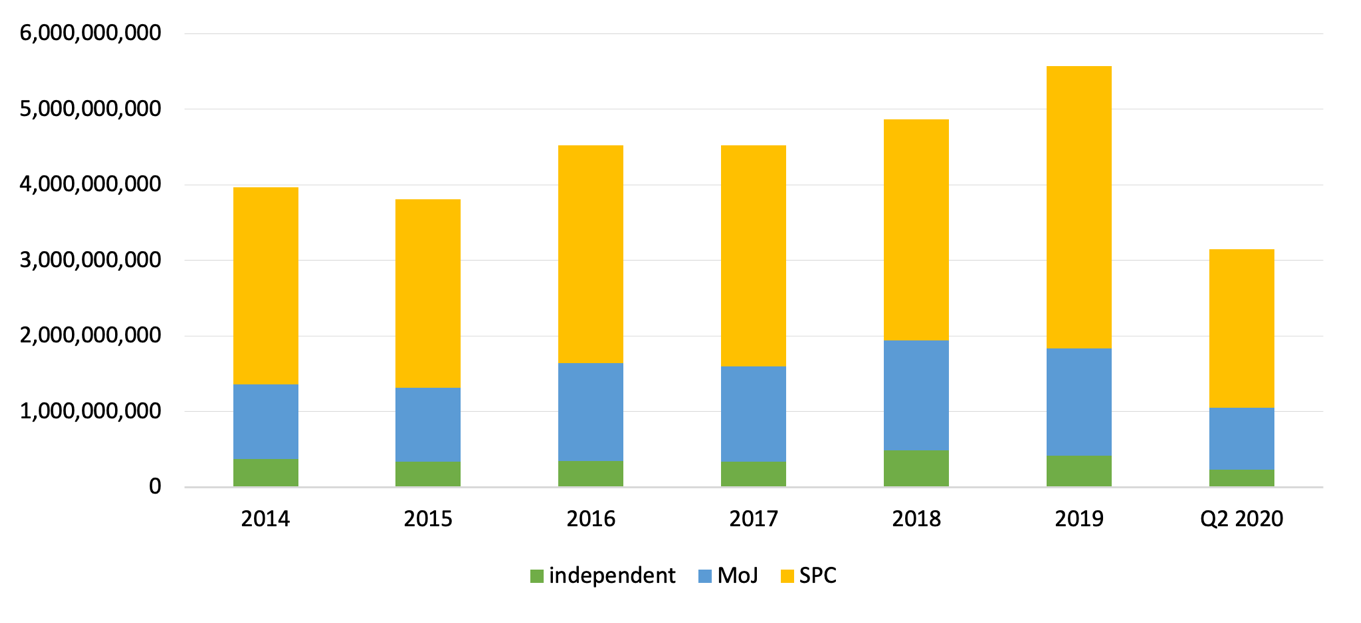

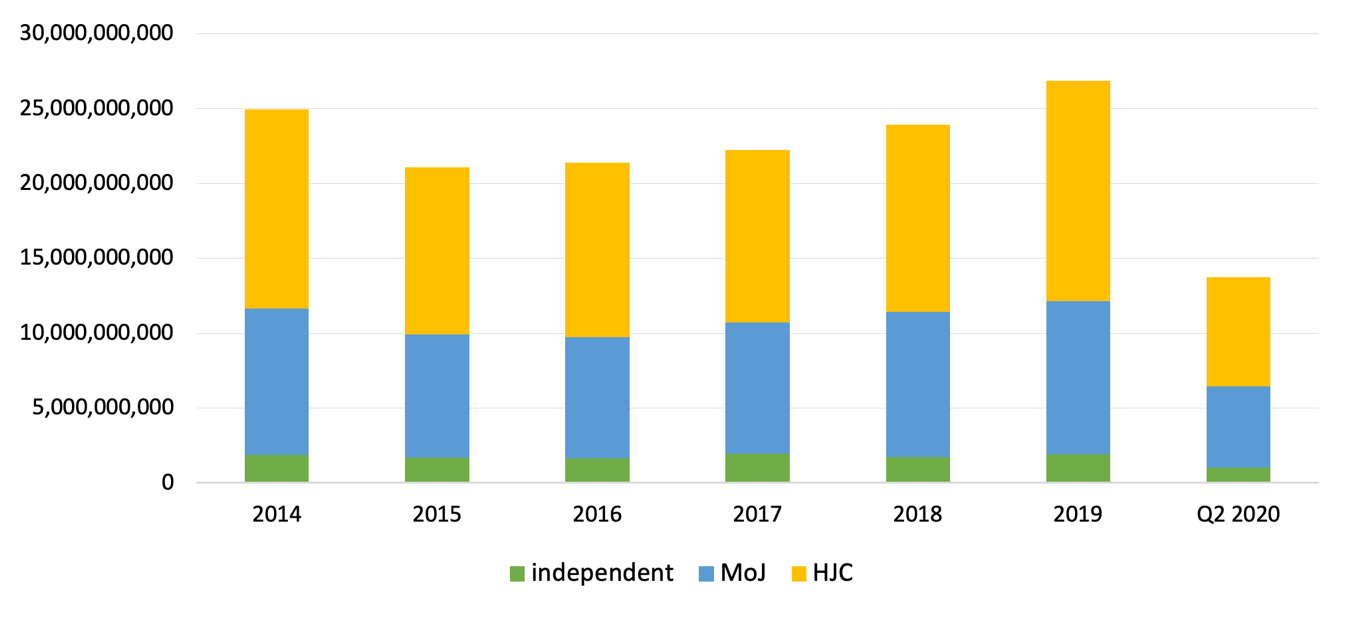

- Expenditures on the court system have continued to grow

since 2015, after a sharp decline following the public sector wage bill

reduction. The court system expenditure was nearly RSD 25

billion in 2014. In 2015 the aggregate wage bill of the system was

reduced significantly – by 13 percent or just short of RSD 2 billion.

The reduction of the wage bill coincided with a permanent decrease in

expenditures for court services due to transferring responsibilities for

carrying out criminal investigation activities from courts to PPOs. The

changes in the Criminal Procedure Code that introduced this change were

adopted in 2013; however, it took until 2015 for these changes to

operationalize and show their effect on the budget. The growth in

expenditures since 2015 due not exceed the reductions in the services

expenditures and the wage cut that was still in effect at the end of

2017 (i.e., 1.5 percent in 2016 and 3.8 percent in 2017).

- On an aggregate level, in the case of the court system

expenditure units, which act as IBBs, there is a steady share

of budgets managed by MoJ and HJC. HJC is, on average, managing

around 58 percent, while MoJ is responsible for the remaining 42

percent. The reason for the stability of the shares managed by one

versus the other institution is that there was virtually no shift in

responsibilities over the part of the budget financed by MoJ and HJC in

the observed period. The mentioned drop-in services expenditure in 2015,

which is managed completely by HJC, was compensated by the higher cuts

in wage bill in the part of the budget under MoJ management.

- Court budget expenditures grew steadily from 2016 to

2019, after a sharp decline in 2015 due to moving expenses for criminal

investigations to PPOs from the courts. Court system

expenditures were nearly RSD 25 billion in 2014. However, in 2015 the

aggregate wage bill of the system was reduced significantly – by 13

percent or just short of RSD 2 billion – as responsibility for the

direction of criminal investigations was transferred from the courts to

Pos in order to ensure the independence of investigations. Overall court

expenditures grew by 1.5 percent in 2016, 3.8 percent in 2017, and 7.6

percent in 2018. Courts that act as DBBs, marked “independent” in Figure

148 below, are shared in the trend.

- The shift in investigative responsibilities did not

affect the relative spending by MoJ and the HJC on the IBB

courts. On average, the HJC managed

approximately 58 percent of the non-employee budgets for those courts,

while the MoJ was responsible for the remaining 42 percent. After the

2015 transfer of investigative responsibilities, non-employee

expenditures were managed completely by HJC and corresponded to cuts in

the wage bills managed by the MoJ.

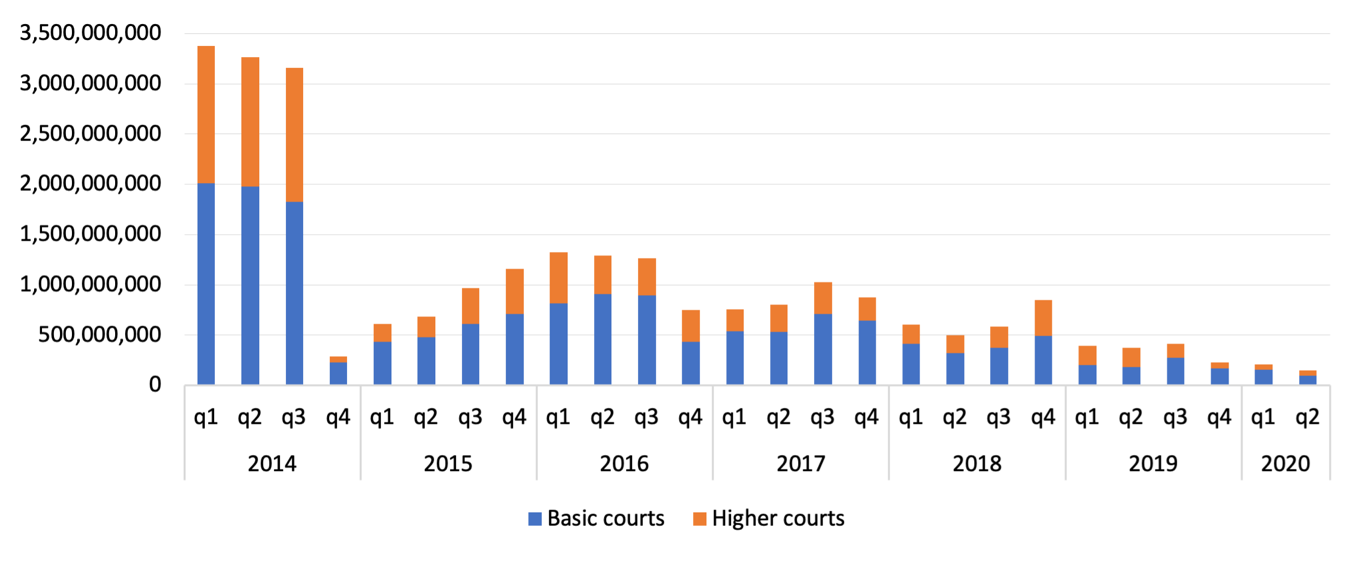

Figure 149: Court system total expenditures, 2014-Q2 2020, excluding

expenditures financed from court fees.

Source: Budget execution reports of judicial institutions and WB

calculations

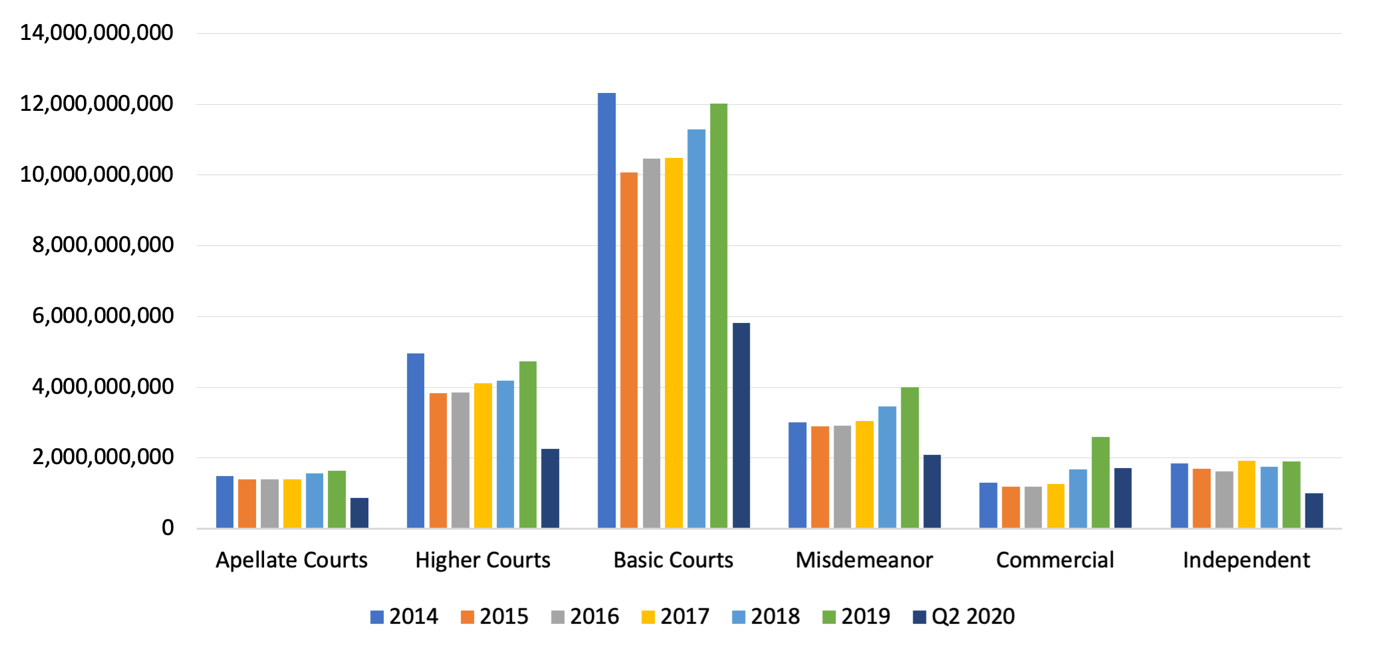

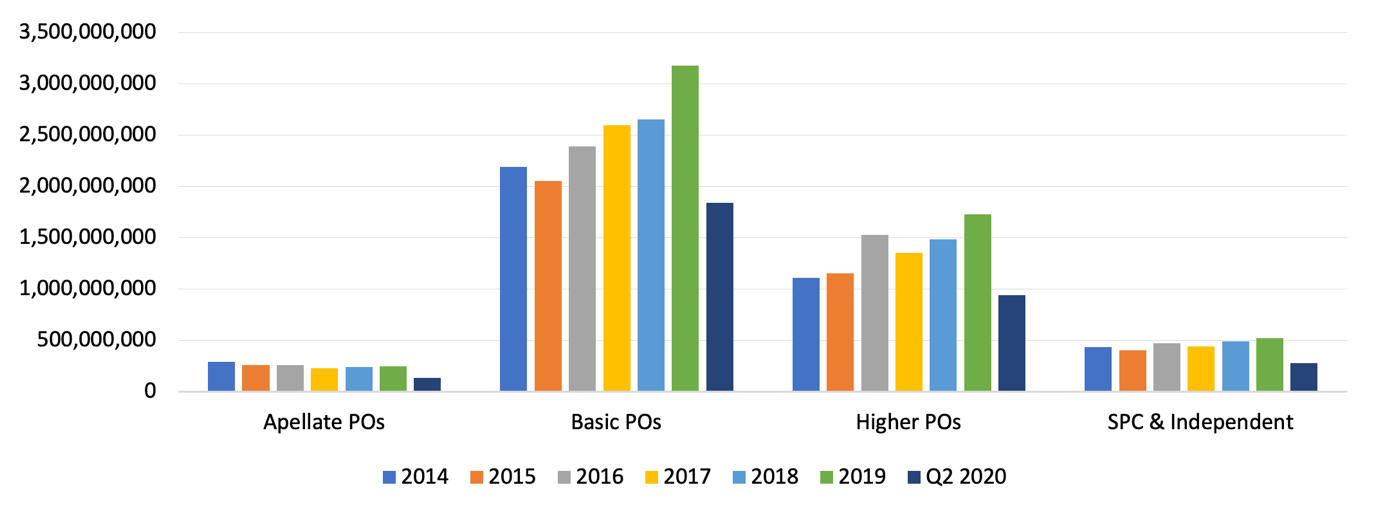

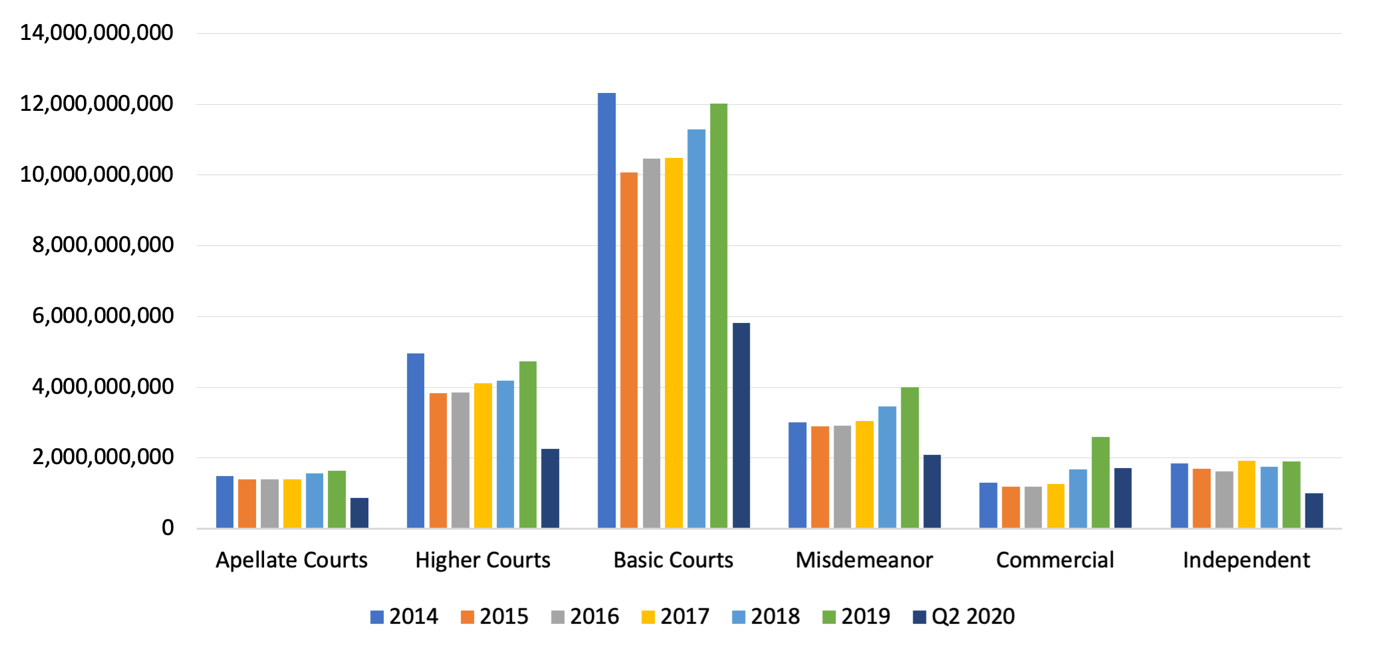

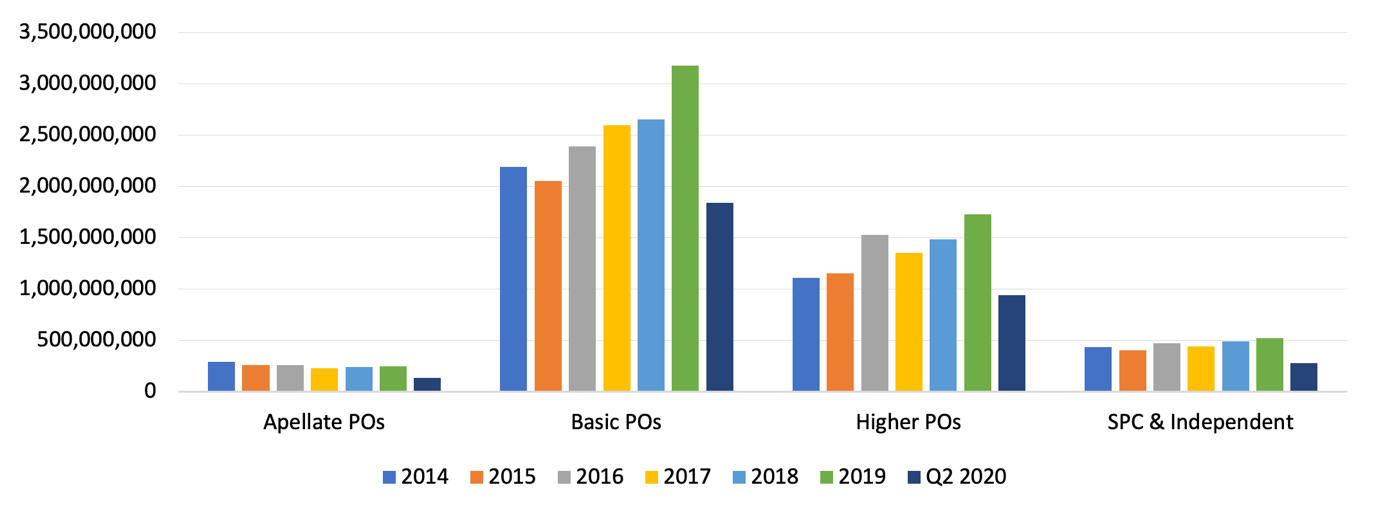

- Basic and Higher Courts absorbed most of the expenditure

cut in 2015, both in relative and absolute terms. Since these

two sets of courts are the largest components of the court system, their

salaries constituted almost half of the entire system budget. From the

total of RSD 2 billion salary decrease in 2015, 1.4 billion was taken

from the wage bills of these courts. All other courts (i.e. Appellate,

Misdemeanor, and Commercial) had smaller decreases in their

budgets.

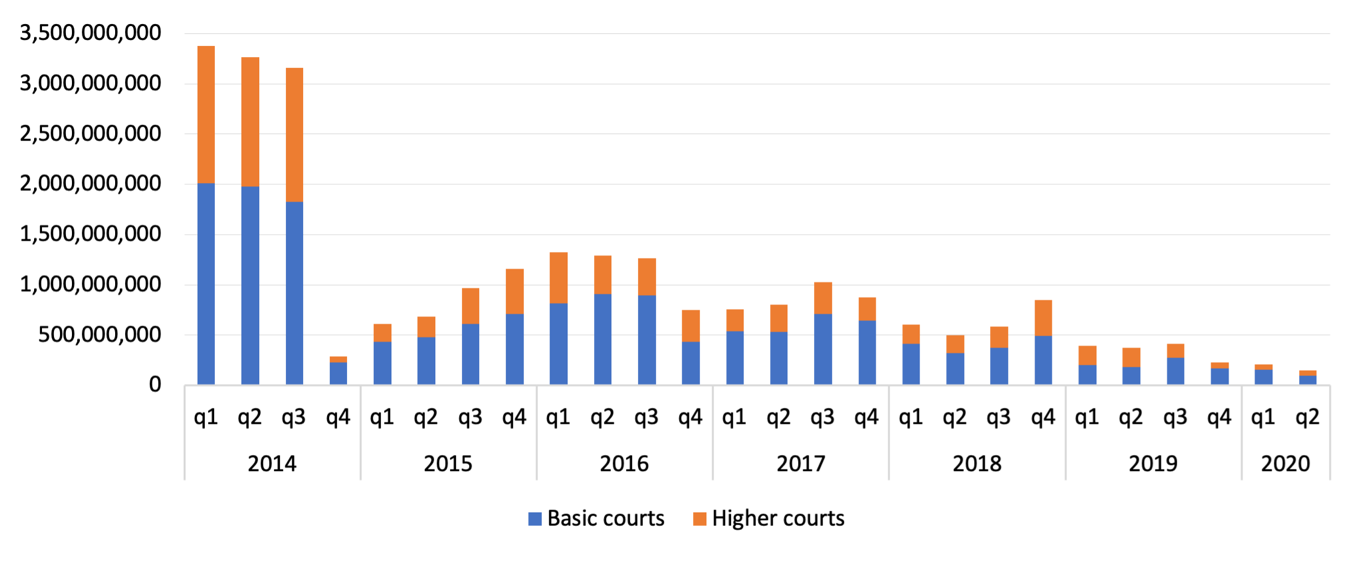

Figure 150: Court system total expenditure, by type of court, 2014-Q2

2020

Source: Budget execution reports of judicial institutions and WB

calculations

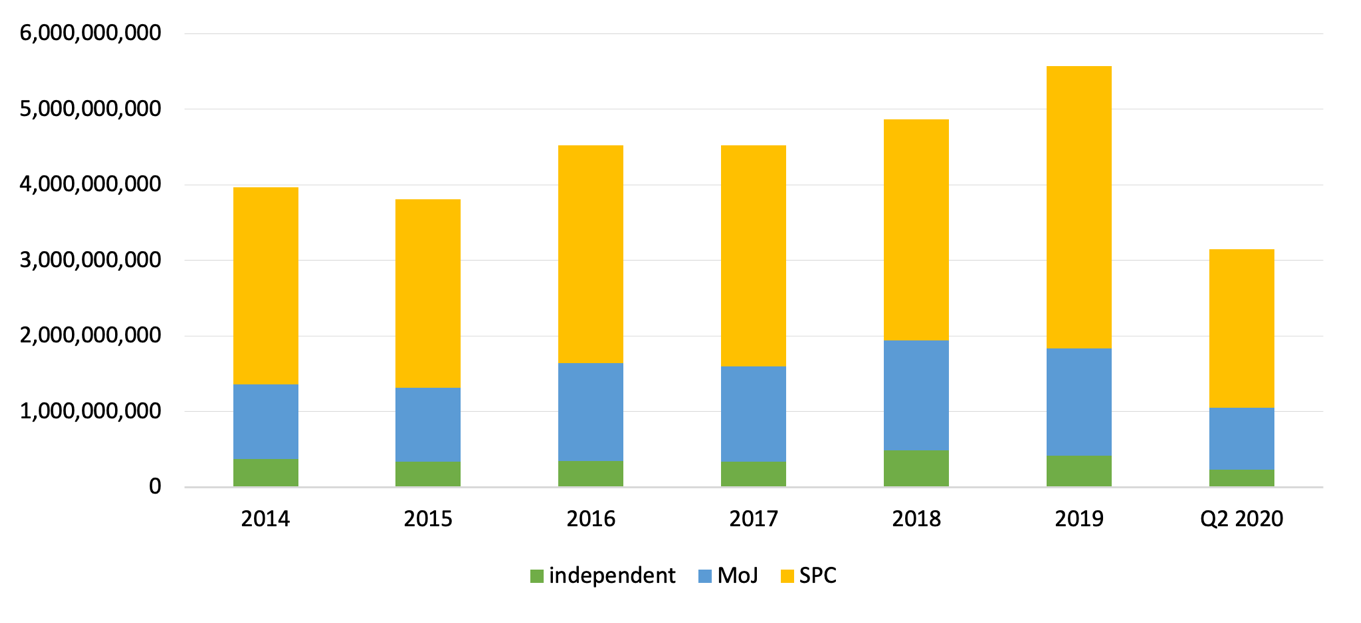

- Prosecutorial expenses also dropped in 2015, but this was

offset starting in 2016 thanks to increases in the service-related parts

of PPOs’ budgets. The increases were

due almost entirely to year-end transfers from budgetary reserves to

cover the significant arrears that PPOs generated each year, discussed

in more detail below, and which totaled more than 600 million in 2016.

The increase in expenditure levels continued at a stable pace of around

8 percent on average.

Figure 151: Prosecution system total expenditure, 2014-Q2 2020

Source: Budget execution reports of judicial institutions and WB

calculations

- Different types of PPOs had very different expenditure

patterns from 2014 to 2019. All PPOs had cuts in the gross

wages in 2015, but the transfer of investigative responsibilities

triggered an increase in Higher PPOs expenditures from RSD 169 million

in 2014 to RSD 319 million in 2015. On the other hand, Basic PPOs

services were kept steady in 2015 and increased from RSD 3443 million in

2015 to RSD 518 million only in 2016. The available data did not offer

an explanation of the one-year lag.

Figure 152: Prosecution system total expenditure, by type of PPO,

2014-Q2 2020

Source: Budget execution reports of judicial institutions and WB

calculations

Judicial System Financing

Sources ↩︎

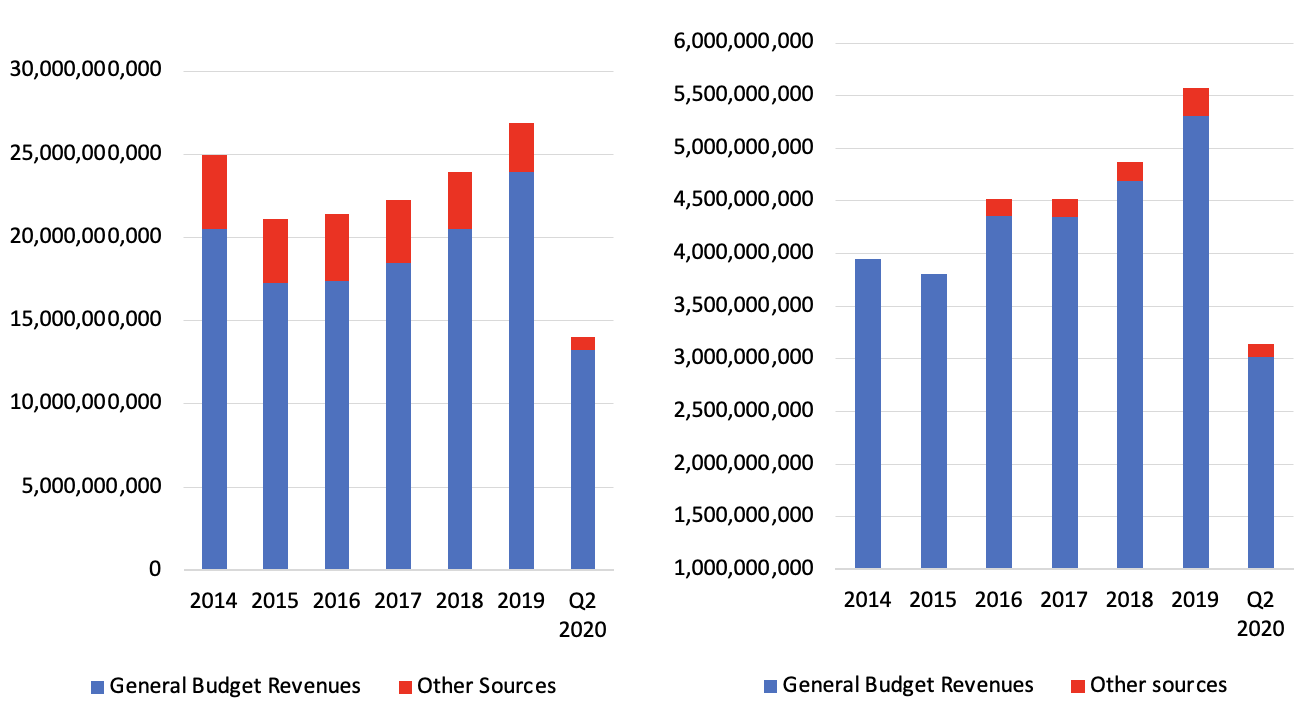

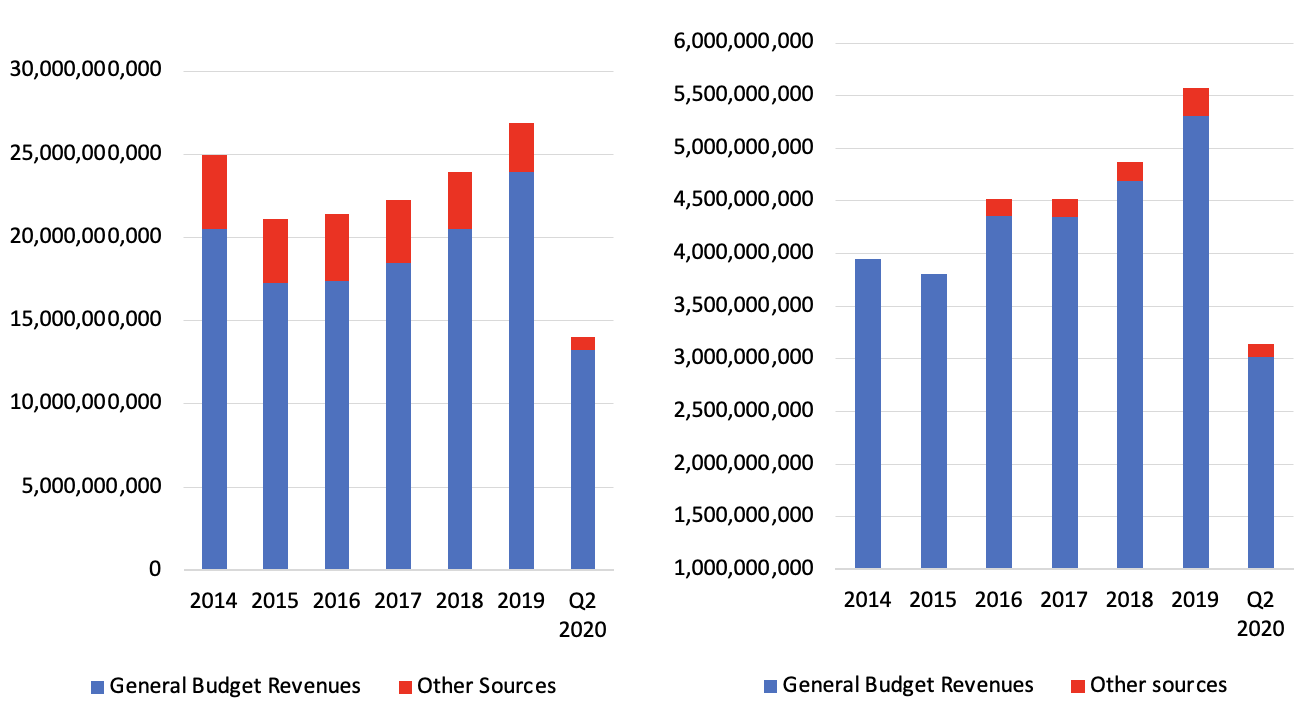

- The judicial system in Serbia was financed predominantly

from general budget revenues. These revenues moved in the narrow range

between 81.3 and 83 percent of the courts’ budgets from 2014 until 2019.

and between 96.1 and 96.4 percent of the share of the budget for the

prosecutorial system in the same period.

Figure 153:Total expenditure, by source, 2014-Q2 2020, court system

(left) and prosecutorial system (right)

Source: Budget execution reports of judicial institutions and WB

calculations

- Collected court fees, included in the “other sources”

category in Figure 152 above, made up close to 20 percent of court's

budgets and only around 3.5 percent of the prosecutorial system

budget. Collected court fees made up more than 90 percent of

the ‘other sources’ category; the rest of the revenues in this category

consisted primarily of donations, loans, and EU support used for capital

projects.

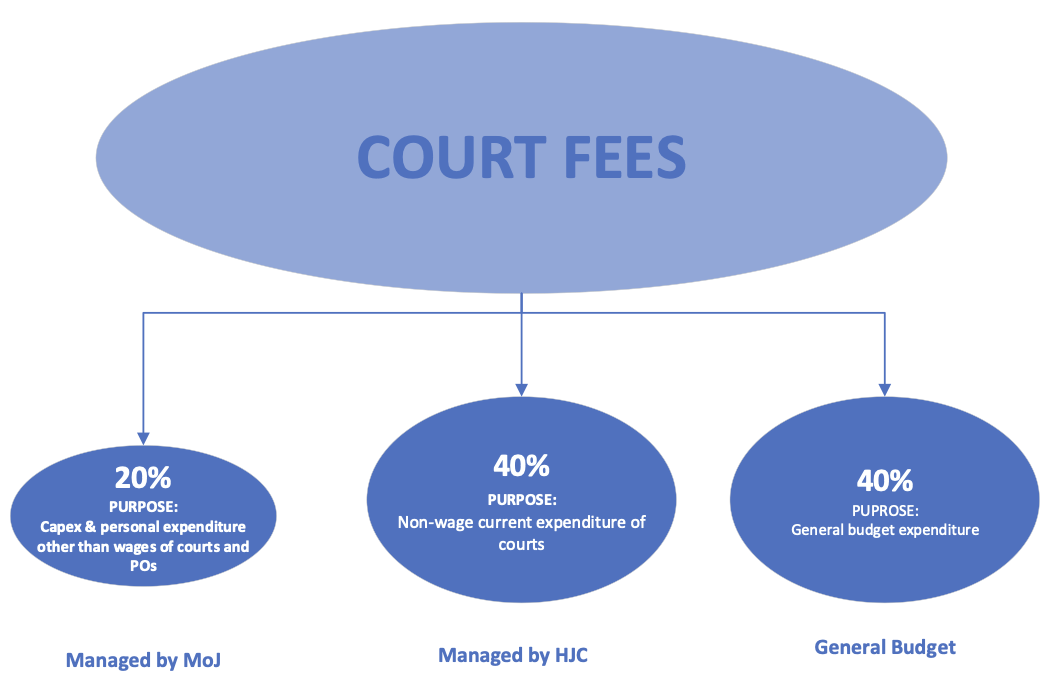

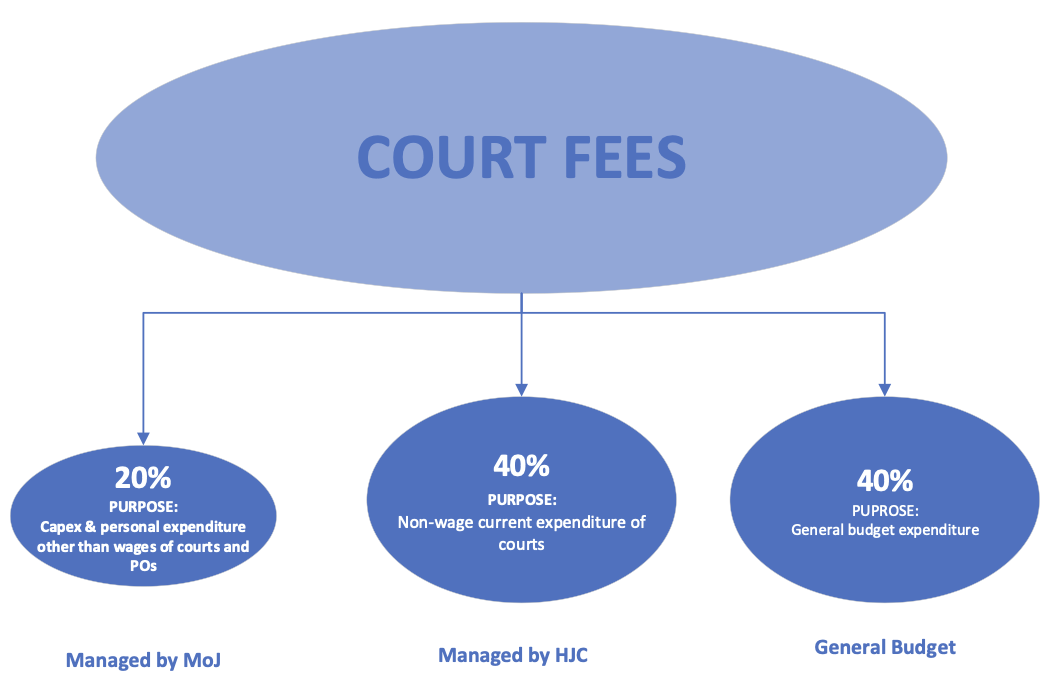

- Budgeting and expenditure allocation of own court fees is

unclear. According to the Law on Court Fees (LCF), 40 percent of court fees are to

be used for the current expenditure of courts, 20 percent is distributed

for non-wage related expenses of public servants from courts and PPOs

and capital expenditures, and the remaining 40 percent represent general

budget revenue and do not serve the purpose of judicial system financing

in any sense. However, court fees are shown only as a gross figure in

the budget and are not explicitly distributed to the appropriations

financed from this source that appear under budgets of different

segments of the court and prosecutorial system. Starting from 2017, they

are allocated across the budgets; for instance, each basic court and PPO

knows the gross amount they will receive. However, justice institutions

are still not aware of what will get financing from this source.

Finally, budget execution data shows that, in practice, the mix of

appropriations financed from court fees in favor of both courts and PPOs

includes virtually all expenditure types. There is no mechanism to

follow if the expenditure is in line with what the LCF

prescribes.

Figure 154: Court fees distribution matrix

- It is unclear what the distribution mechanisms are when

allocating the financing from court fees between courts and PPOs and

across individual courts and PPOs, rendering this procedure

untransparent. The distribution seems to consider institutional

size (i.e. staffing levels), but there is no formal argument to support

this observation. To the best of our knowledge, the MoJ and HJC have not

developed transparent criteria to perform these splits. It seems that

the distribution of funds is performed on a need basis where MoJ decides

arbitrarily on the priority level of individual requests. This should

not be interpreted as an issue of improper use of funds but rather a

practice that should be eliminated to increase transparency and

accountability.

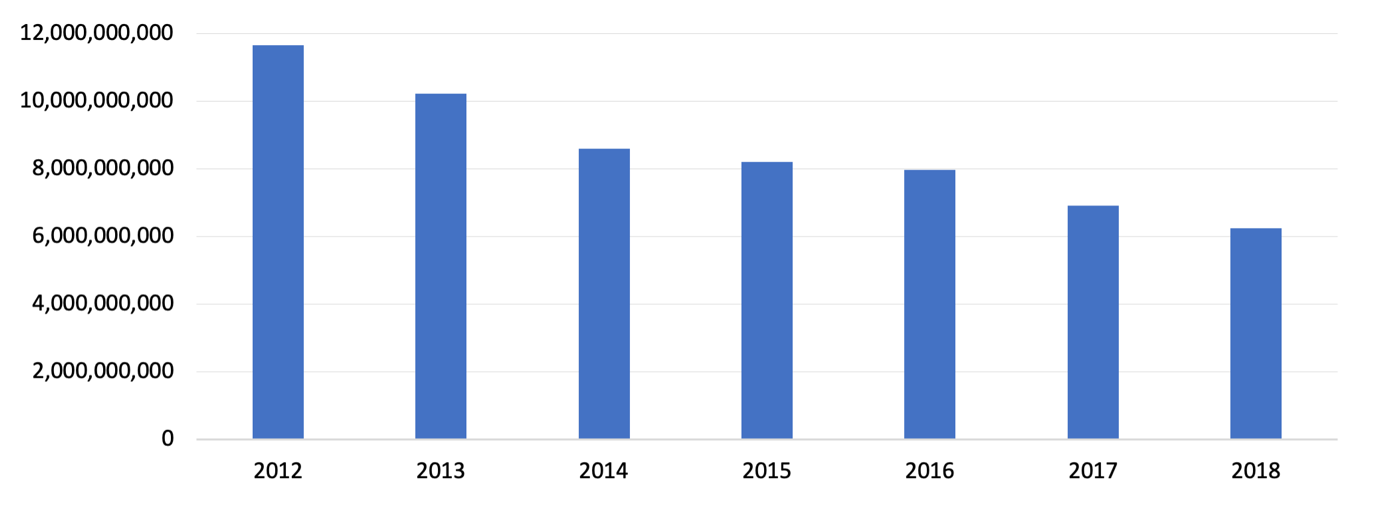

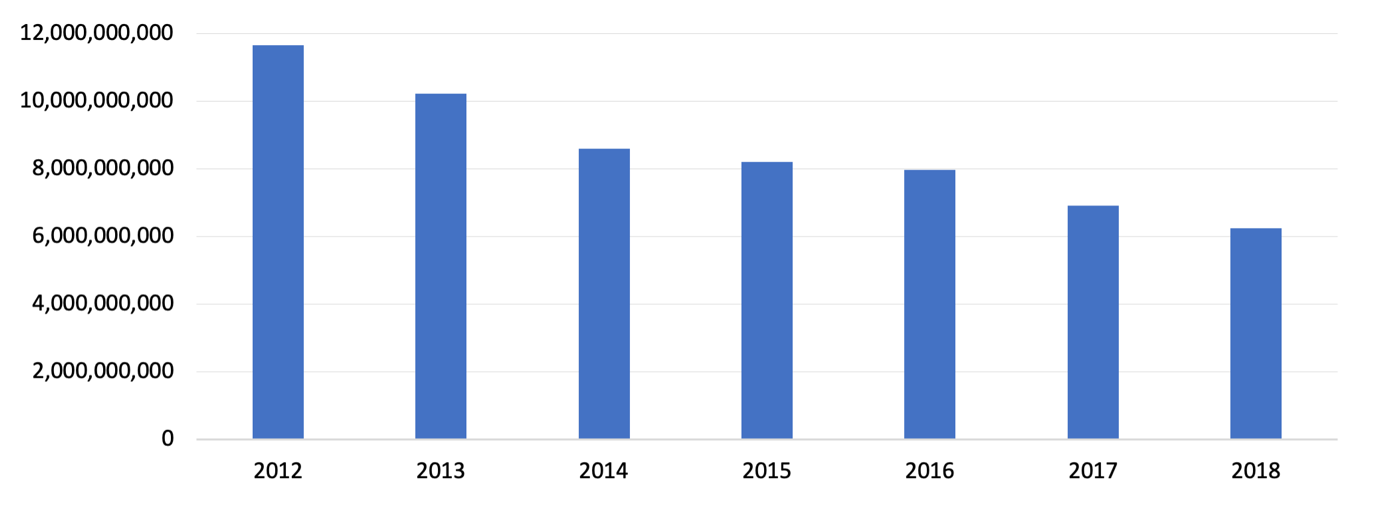

- The level of court fees declined by more than 46 percent

between 2012 and 2018, after the

introduction of enforcement agents in 2012 and private notaries in

2014. Court fees dropped by 26 percent from 2012 (RSD 11.6

billion) to 2014 (RSD 8.6 billion in 2014). Court fees then stabilized

at approximately RSD 8 billion until legislative changes to enforcement

procedures, including the introduction of enforcement agents, triggered

a further drop of more than RSD 1 billion in court fees in 2017. The

fall continued in 2018, in which collected fees dropped to RSD 6.2

billion.

Figure 155: Level of court fees, 2012-2018

Source: MoJ

- In the absence of detailed records, court representatives

estimated only 30-40 percent of assessed court fees were

collected. The Law on Court Fees requires

debtors to be told that a court fee must be paid within eight days, and

collection should be assigned to enforcement agents if it is not paid.

In practice, however, these provisions were not applied. There were

attempts to increase the rate of collection in recent years through

changes in the Law which now allows court fees to be paid through Tax

Stamps – however, the lack of records does not allow to measure the

extent to which this is reflected on the collection rate. This payment

method is definitely more practical, but the question remains whether it

increases fee payment discipline.

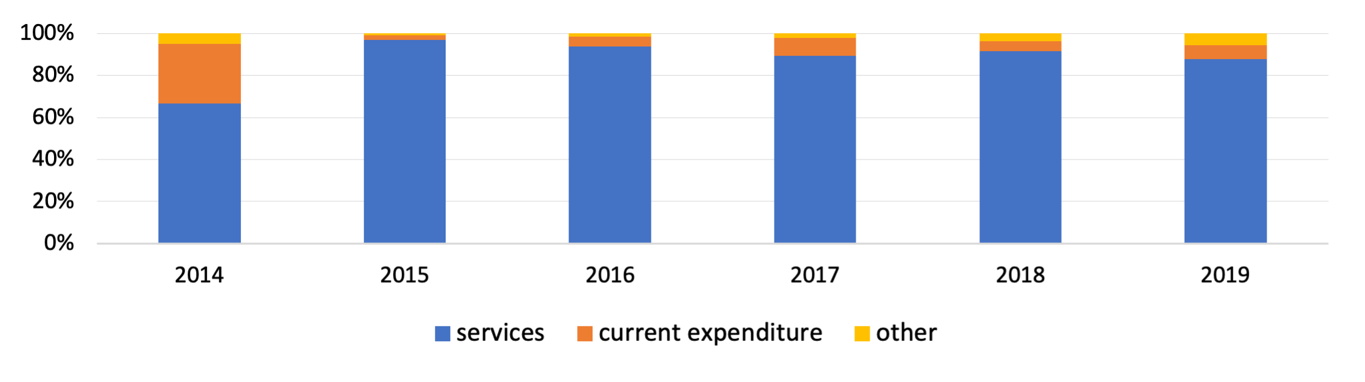

Budget Structure ↩︎

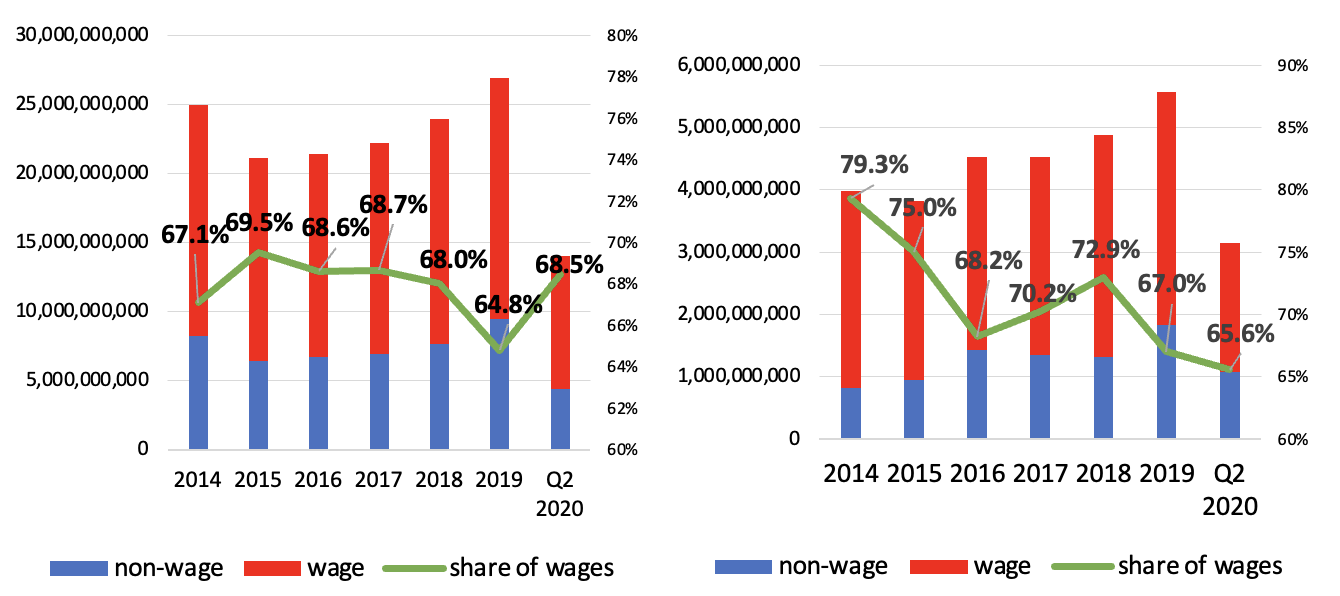

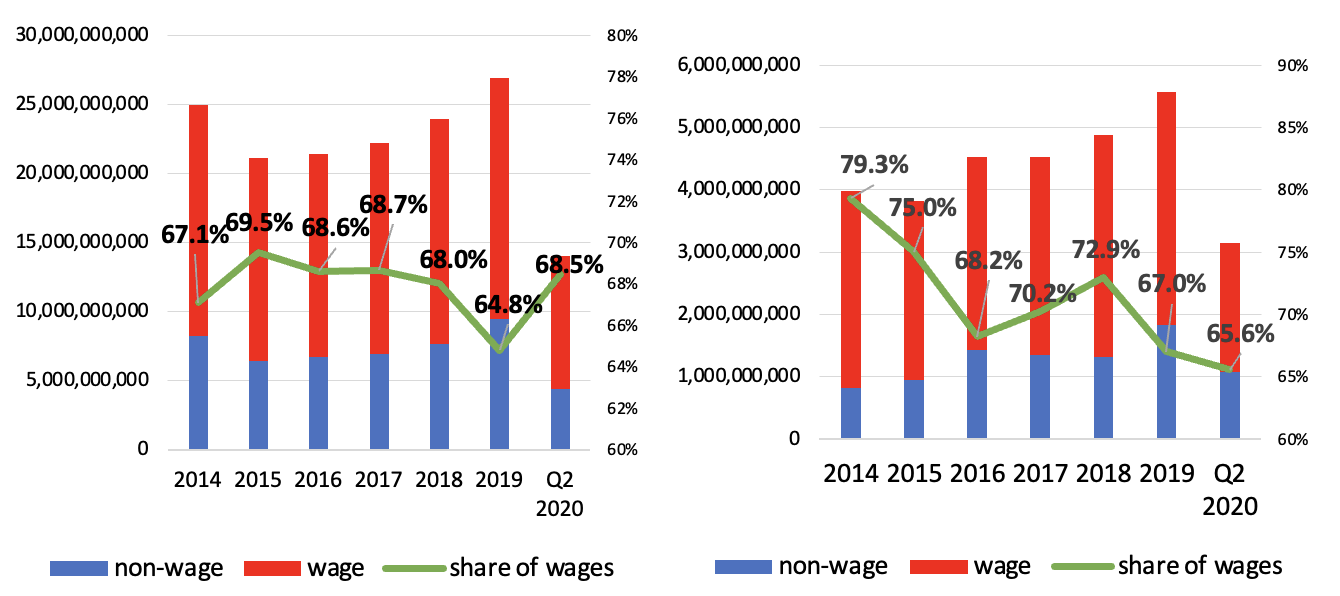

- The budget structure of the judicial system in Serbia is

strongly skewed towards wage and wage-related expenses. In the

case of courts, this share ranged around 68.5 percent over the 2014-2018

period (see Figure 156), while the prosecutorial system share dropped

significantly over time – from 79.3 in 2014 to 70.2 percent in 2017 and

started to recover to reach nearly 73 percent in 2018. This earlier drop

was a result of increased service-related expenditure due to the

transfer of investigation processing responsibility. The share of wage

expenses in the expenditure structure of the court's system was

maintained because the drop in services expenditure was matched by the

decrease in wages from 2015 onwards. At the same time, the service

expenditure that spilled over from courts to the PPOs system brought

down the share of wages in the prosecutorial system as non-salary

expenditures increased.

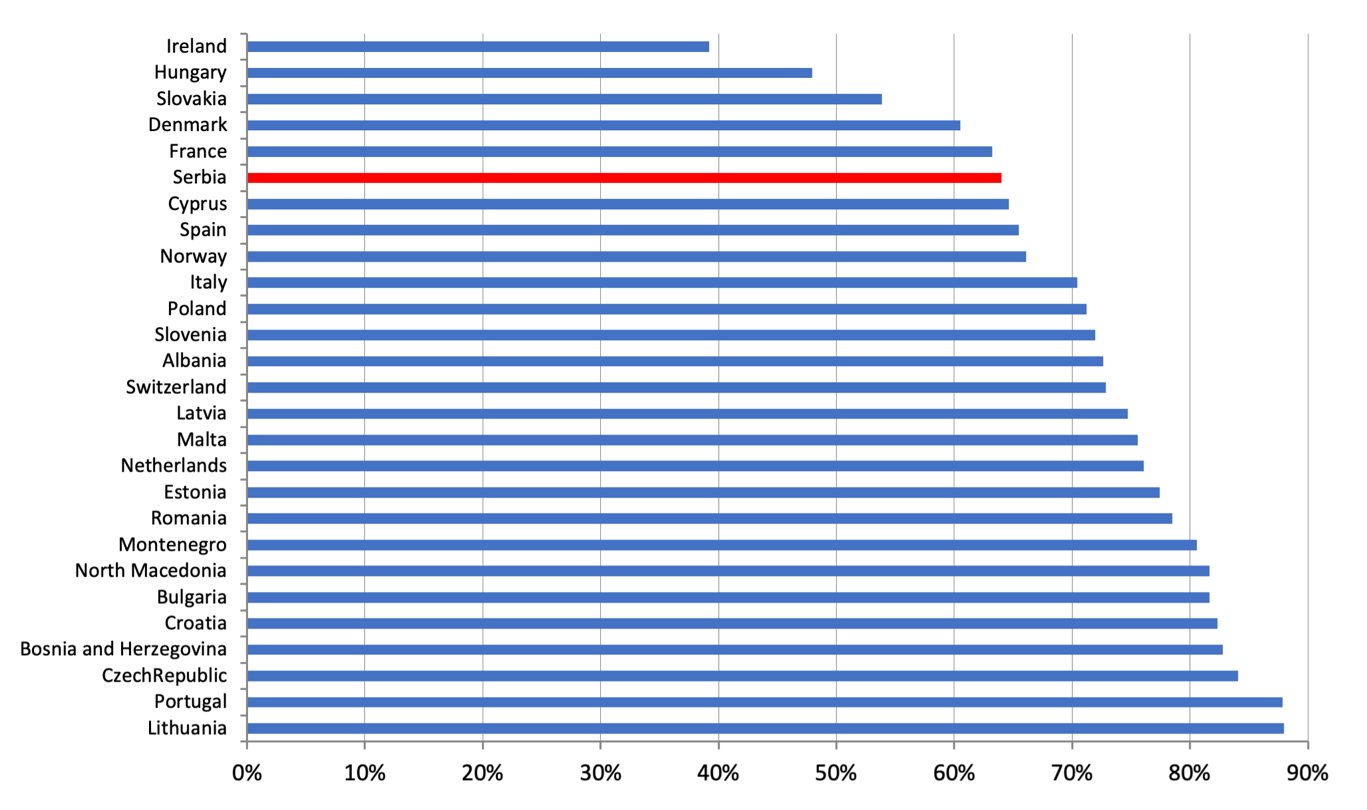

- Nonetheless, the percentage of court system expenditures

for wages was much lower for Serbia than it was for most other European

countries and most of Serbia’s regional peers. As shown by

Figure 155, wages for judges and court staff made up only 64.8 percent

in 2016, compared to the median figure of 72.9 percent. Wages and

wage-related expenses made up roughly 68.5 percent of courts’

expenditures from 2014-2020 (see Figure 156); the drop in expenditures

triggered by the transfer of investigative responsibilities was

accompanied by the drop in wage expenditures beginning in 2015.

Figure 156: Court system, share of wages, Serbia and EU, 2018

Source: CEPEJ 2020 Report and budget execution reports

- The share of wage expenses for the prosecutorial system’s

budget went from 79.3 percent in 2014 to 70.2 percent in 2017 due to the

transfer of investigatory expenses from the courts to PPOs and the

resulting increase in non-wage expenses. However, slower growth

of non-wage expenses in 2018 pushed the percentage back to just below 73

percent 2018. During 2019, however, services expenditure grew by almost

15 percent, which lowered the share of wages back to the level below 70

percent. This is also shown in Figure 156.

Figure 157: Court system (left) and prosecutorial system (right),

share of wages in total expenditure, 2014-Q2 2020

Source: Budget execution reports of judicial institutions and WB

calculations.

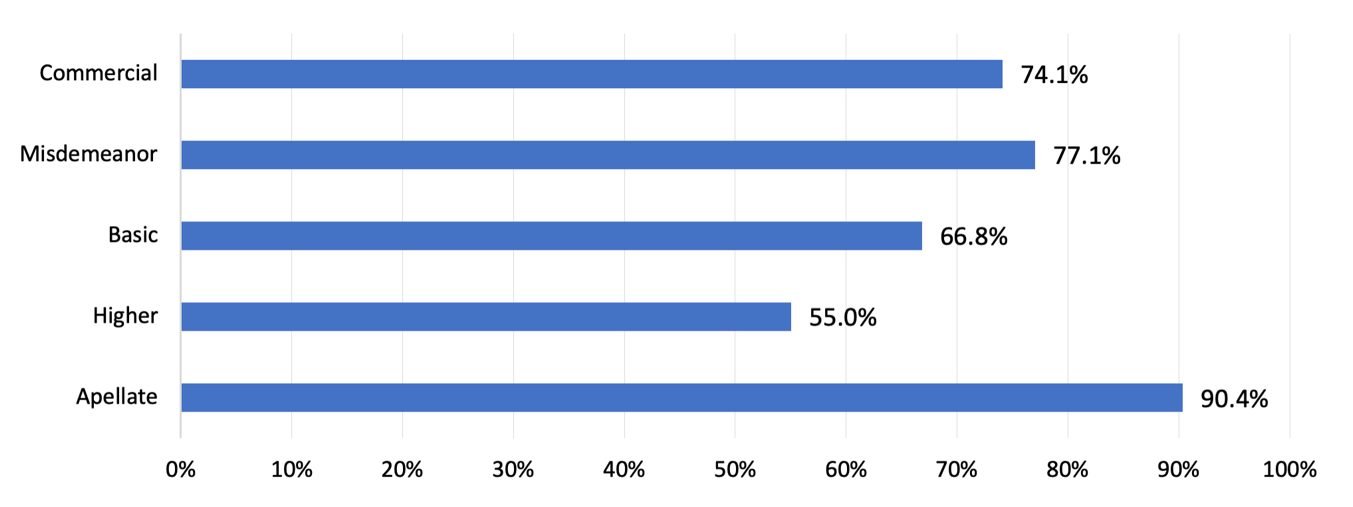

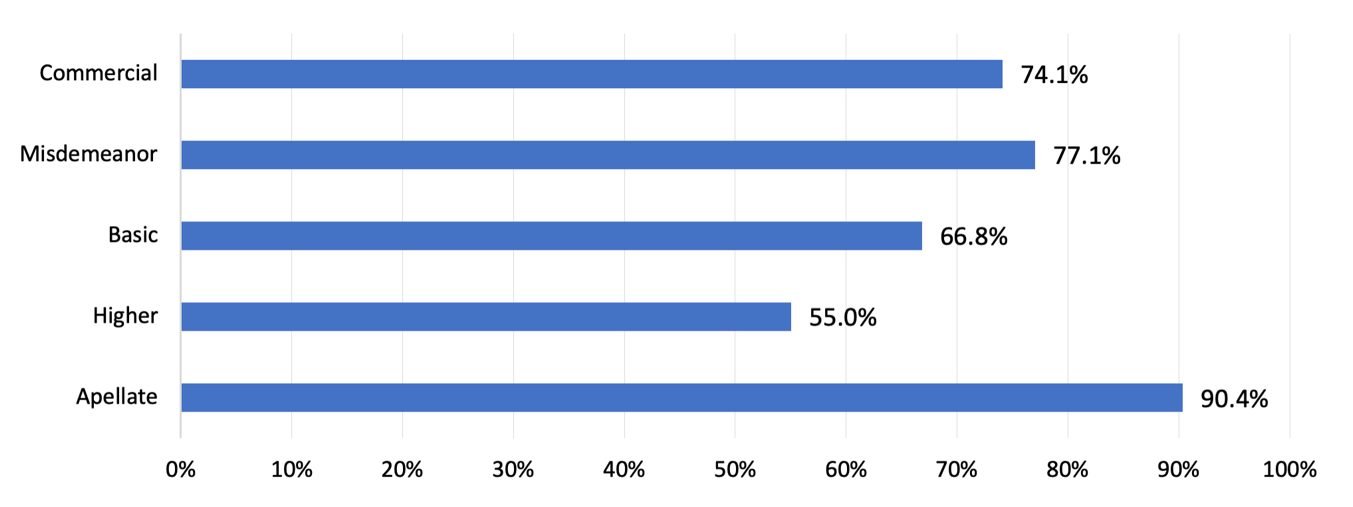

- Higher Courts had the lowest share of wages in their

expenditure structure (55 percent) since they handled more complex

cases, which tended to have high service (i.e., lawyer and expert

witness) costs. They were followed by Basic Courts, which had

66.8 percent spent on wages and other personal expenses. Appellate

Courts, which have less demand for the attorney and expert witness fees,

spend 90.4 percent of their expenditures on wages.

- There were large variations in the wage-to-budget ratios

among the same categories of courts, with courts in areas with lower

populations spending a greater share of their budgets on wages.

For example, the average four-year expense for wages among the Higher

Courts ranged from 36.4 percent in Kragujevac to 71.12 percent in

Valjevo. In the case of Basic Courts, the percentage spent on salaries

ranged from 47.6 percent in Novi Pazar to 79.1 percent in Mionica. This

is unsurprising as any court has certain staffing requirements,

regardless of size. It also reflects less focus on capital and IT

expenditures in smaller courts.

Figure 158: Court system, share of wages, per type of court,2014-2019

(average)

Source: Budget execution reports of judicial institutions and WB

calculations

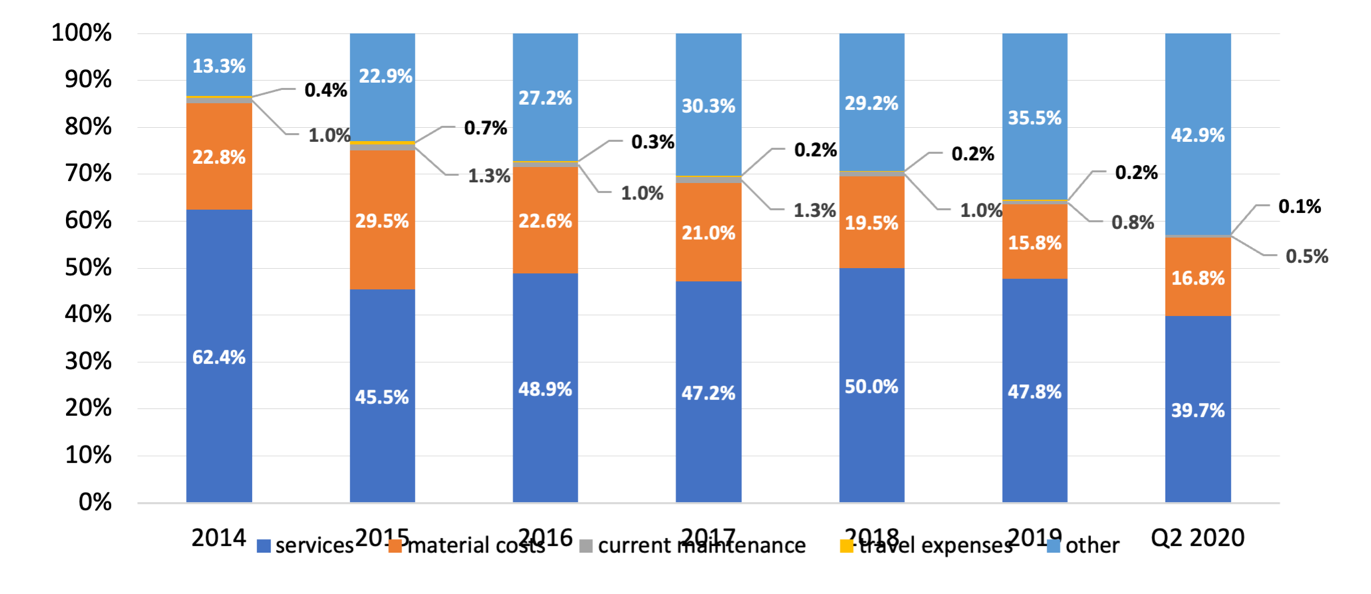

- Non-wage court expenses were relatively stable from

2014-2019, except for the steady increase in penalties and fines paid by

courts through the enforced collection process (discussed further below)

and a decline in the share of total expenses consisting of services

related to court proceedings, such as legal aid attorney fees and expert

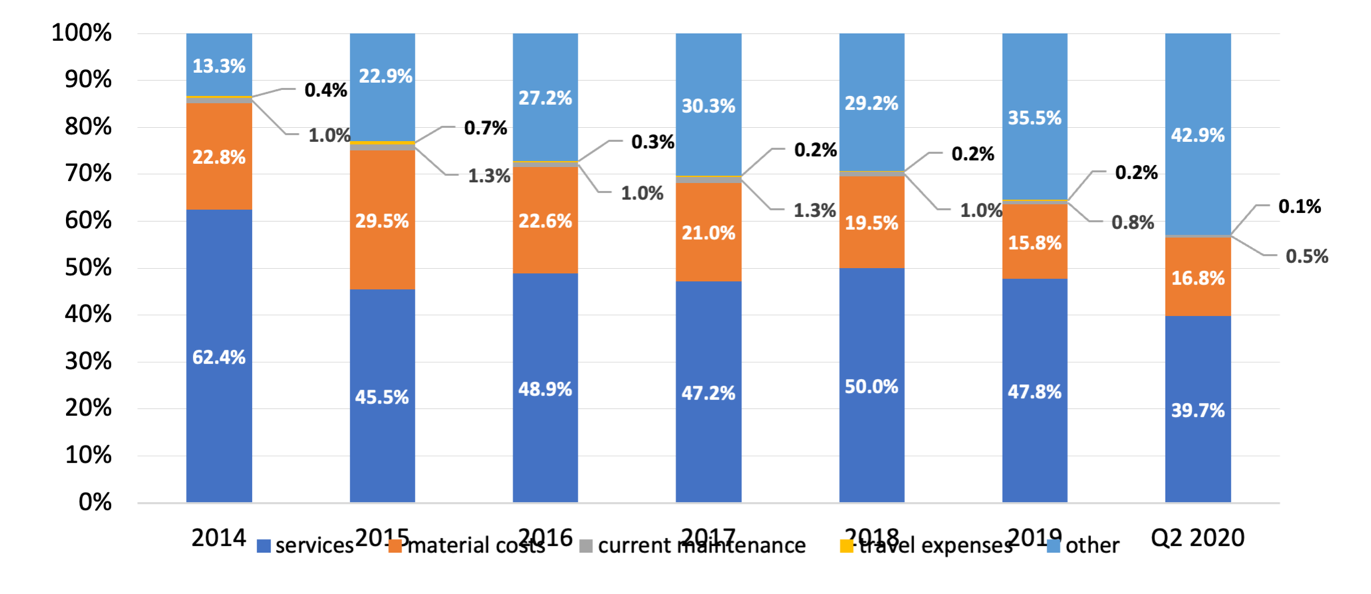

witness fees. In 2014, the ‘services’ item constituted 62.4

percent of the total non-wage court expenditure. However, the shift of

responsibilities over managing the criminal investigation process

between courts and PPOs resulted in a substantial decrease in these

expenditures in 2015, and hence their share of total expenses dropped to

an average of 47 percent in the period from 2015 to 2019. Penalties and

fees were included in “other expenses,” which increased from 13.3

percent in 2014 to around 30 percent in 2017 and 2018.

Figure 159: Court system, structure of current non-wage expenditure,

2014-2018

Source: Budget execution reports of judicial institutions and WB

calculations

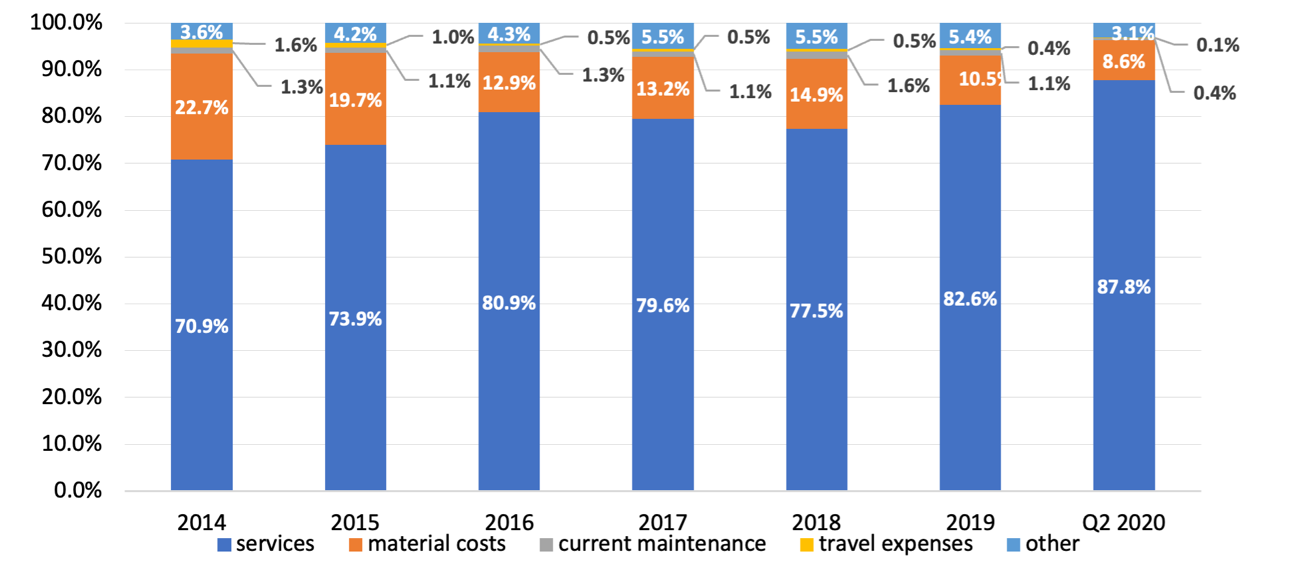

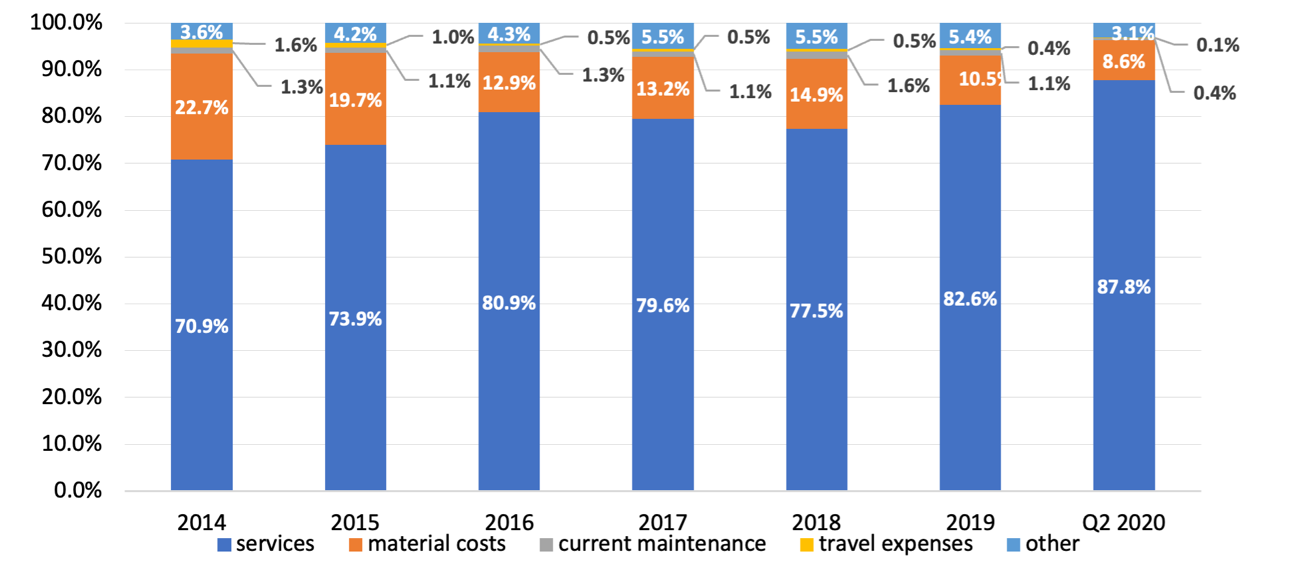

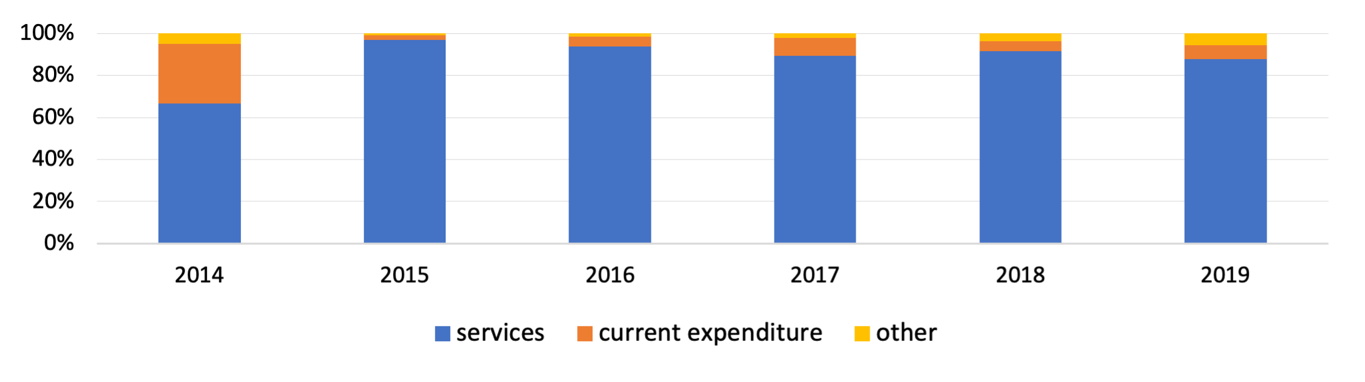

- The shift in investigatory responsibilities left the

prosecutorial system with an increase in its budget share for ‘services’

expenditure – from 70.9 percent in 2014 to almost 83 percent in

2019. The rise in services expenditures was responsible for the

entire increase in prosecutorial system expenditures over the four-year

period. Material costs such as utilities and office supplies, the

second-largest category, remained at around RSD 180 million, so their

share of expenses shrank from 22.7 percent in 2014 to 10.5 percent in

2019. Other categories of expenses included current maintenance and

travel expenses as well as ‘fees and penalties’.

- There were significant differences in the structure of

expenditures among PPOs within the same category due to the

varying interpretation of Article 261 of the Criminal Code and

its language about the payment of costs incurred during an investigation

by the courts or PPOs. In some cases, the prosecution offices took over

all expenses related to the investigation, while in some, courts are the

ones covering expenses if an indictment is issued. This is covered in

more detail in the following section.

Figure 160: Prosecutorial system, structure of current non-wage

expenditure, 2014-Q2 2020

Source: Budget execution reports of judicial institutions and WB

calculations

- There were significant discrepancies between the amount

deducted from court budgets and added to PPO budgets for investigatory

expenses. With some fluctuations, PPO budgets for services

increased by RSD 350 million from 2014 to 2017, while the court services

budgets decreased by RSD 1.45 billion in that period. This insufficient

funding for PPOs triggered the acceleration of arrears. Some individual

courts which retained responsibility for at least some increased

expenses also had increased arrears, as discussed in the following

section. This trend changed as in 2018, and 2019 services expenditure

increased in both courts and PPOs compared to 2017, predominantly to

settle previously accumulated arrears.

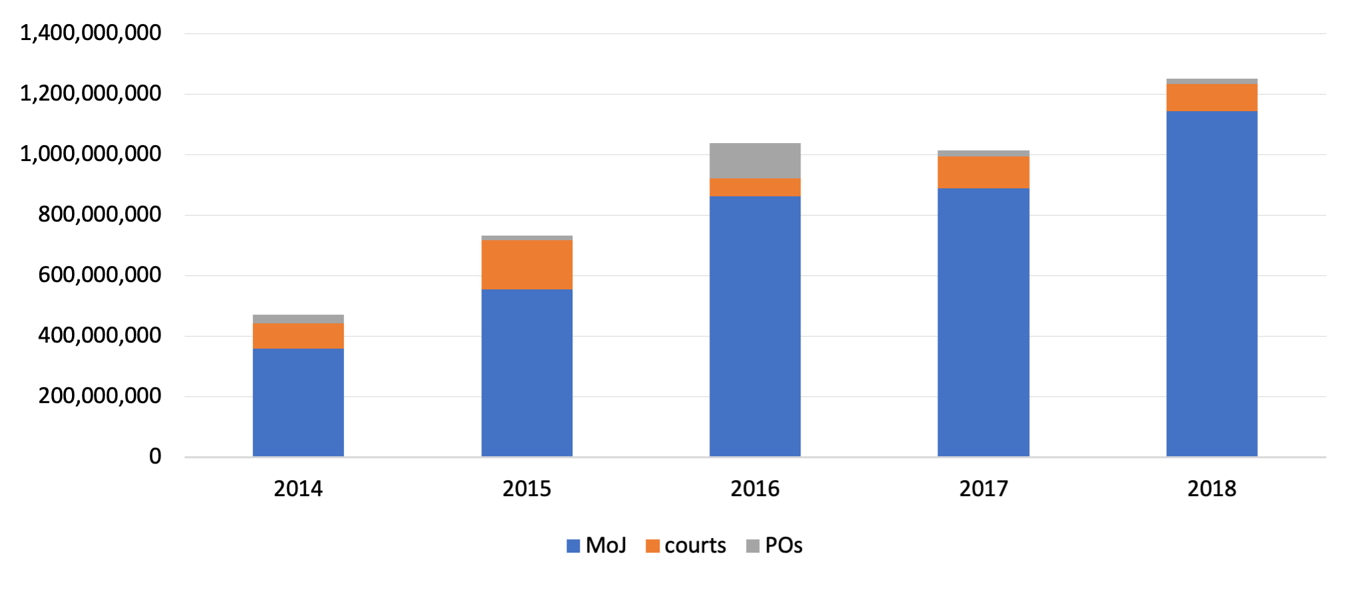

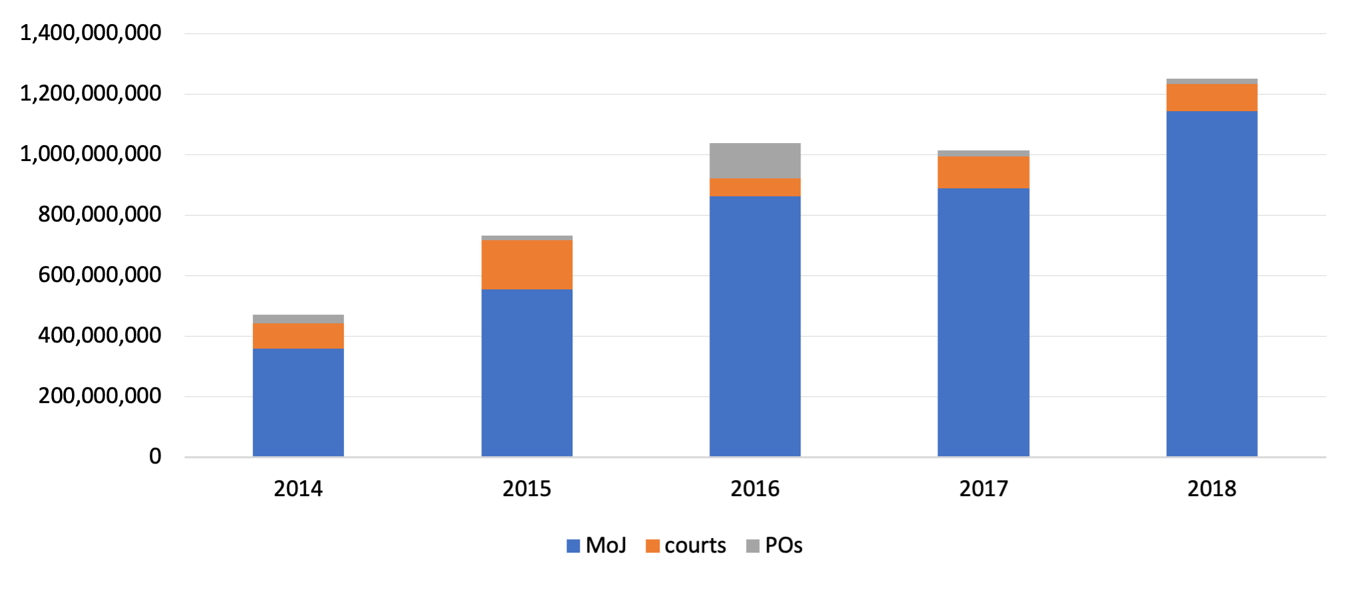

- Capital expenditure grew almost 300 percent from 2014 to

2019, from RSD 479 million to RSD 2.3 billion. This primarily

was due to the accelerated implementation of projects that had been

under consideration for several years, such as the reconstruction of the

Palace of Justice in Belgrade and the Judicial Building in Kataniceva,

which alone account for more than a half of the entire capital budget

over the period. In 2019, almost RSD 1 billion were invested in the new

judicial building in Kragujevac.

- There was substantial progress in the funding of judicial

infrastructure, primarily from external sources. The 2015

addition of the capital budget section of the Budget Law enabled the MoJ

to enter into multi-year contracts, which in turn allowed the

development of more reliable financial plans for capital investment

projects. However, there were still gaps in the capacity of the system

to handle large investment projects.

- The public investment system of the MOJ displayed the

same weaknesses as the overall Public Investment Management (PIM0

framework of the Republic of Serbia. There was a pronounced

pattern of weak project preparation and selection mechanisms leading to

backlogs and poorly performing projects, including those financed by

IFI. Overall, the system lacked formal mechanisms for pre-screening,

selection, prioritization, and monitoring of projects, which undermined

the execution and integrity of the processes.

- Serbia has to continue investments in judicial

infrastructure to prevent further deterioration of judicial buildings

and replacement of existing equipment, as discussed in the chapters on

ICT and Infrastructure Management. During the period under

study, the court system capital budget went from an average of 2.3

percent during the 2010-2013 period to more than seven percent in

2019.

Figure 161: Capital expenditure, judicial system, 2014-2020

Source: Budget execution reports of judicial institutions and WB

calculations

- The MoJ managed large capital investments on behalf of

all judicial institutions, while only a small portion of total capital

expenditures was managed by the judicial institutions

themselves. This is shown in Figure 160, above. Large capital

investment projects began appearing as separate items within the MoJ

budget only in 2015. However, most projects benefitted more than one

judicial institution as many institutions share a single building (e.g.,

a Basic and Higher Court and/or both a court and PPO in the same town).

Formulated as separate projects, it is possible to track their financial

implementation, but since the large majority of them benefit more than

one judicial institution, they cannot be allocated to any of these

institutions in particular but are kept in the financial records of the

MoJ. This adds to the complexity of the budgetary structure and makes it

difficult to assess the budgetary performance of the judicial

system.

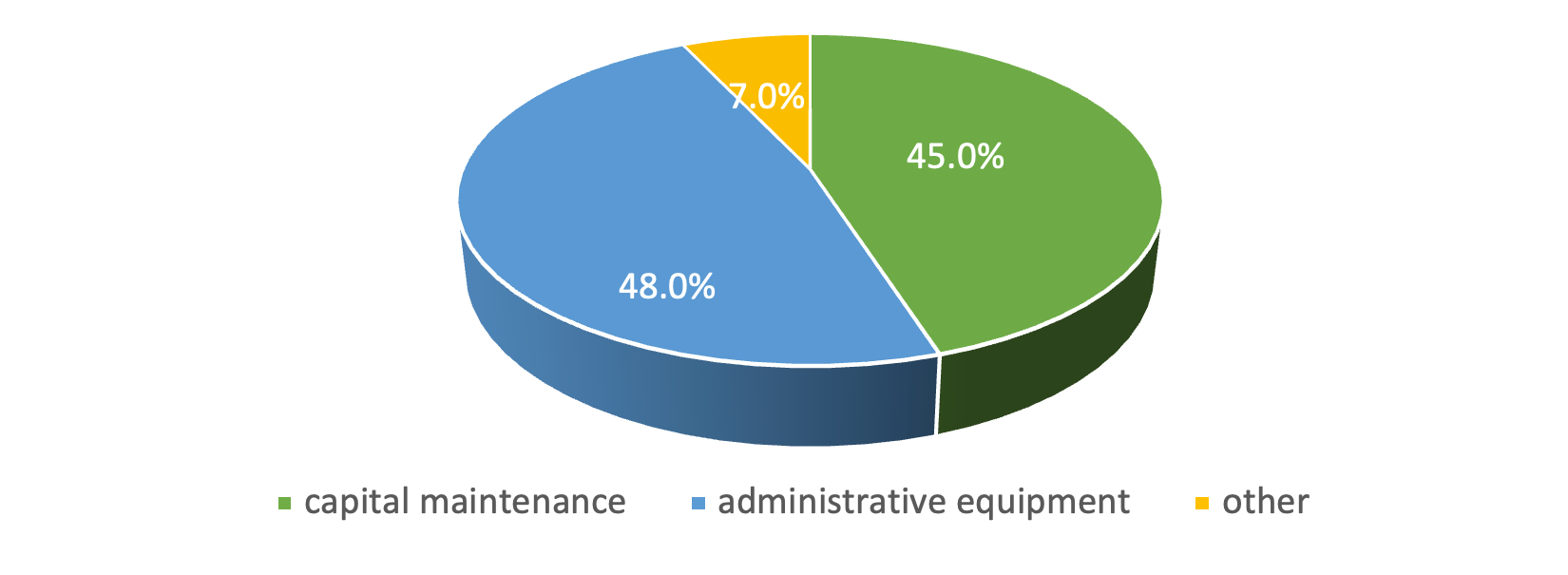

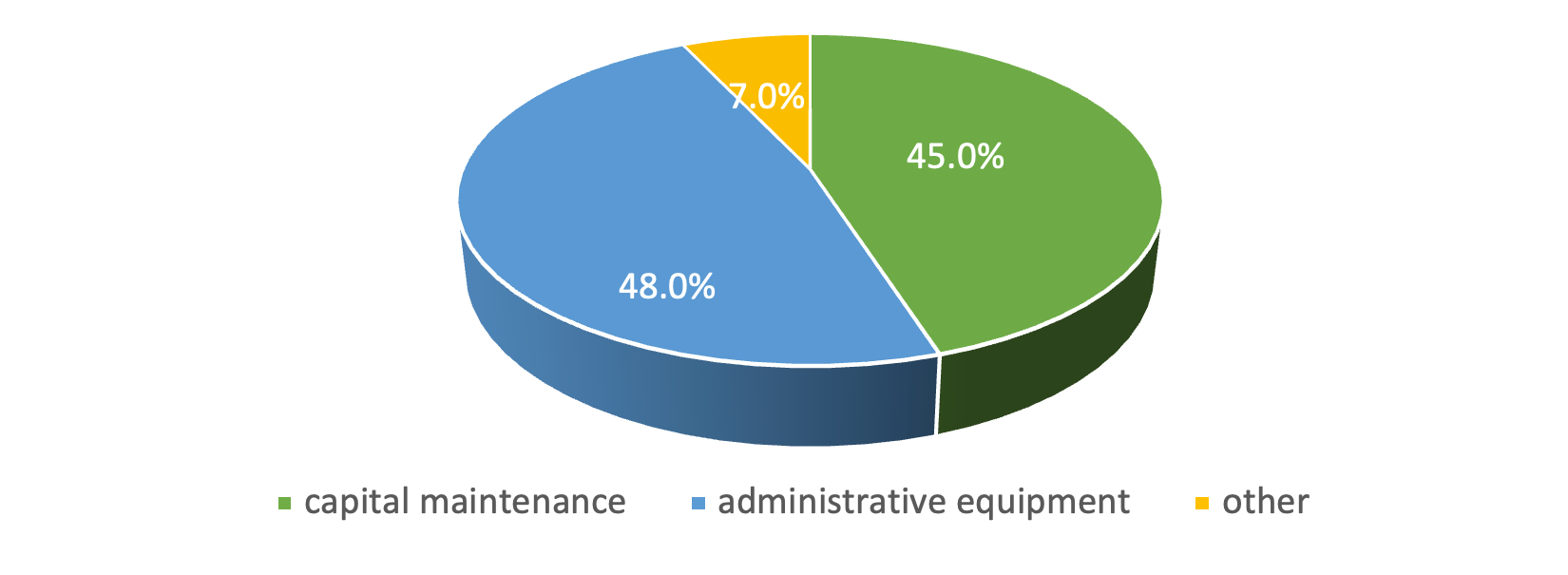

- Most of the MOJ-managed projects involved the

construction or reconstruction of buildings; capital expenditures

managed by courts and PPOs consisted primarily of capital maintenance

(48 percent) and purchase of administrative equipment (45

percent). This is shown in Figure 161 below.

The breakdown of capital expenditure is very stable over the period,

with one exception in 2016 when the “other” category included nearly RSD

89 million for the reconstruction of the Basic and Higher PPO building

in Sombor was reported in the budget of the Higher PPO Sombor. The

remaining portion of the “other” category consisted predominantly of

expenses related to preparing technical documentation for large capital

projects and purchasing security equipment and vehicles.

Figure 162: Structure of capital expenditure, aggregate, average

2014-2019

Source: Budget execution reports of judicial institutions and WB

calculations

- While the Law on Court Organization regulated the authority

over capital and current maintenance of the courts, there was no

official definition of what constitutes capital maintenance assigned to

the MOJ versus current maintenance assigned to the SPC. As a

result, to address emergency situations, the MoJ sometimes financed work

from own-source revenues, based on the provision of the Law on Court

Fees which allowed that “up to 20 percent of court fees can be used for

improving the material status of the employees, CAPEX, and other

expenses”. The 2017 version of the Law on Organization of Courts

consolidated authority for both types of court maintenance expenses in

the MoJ. However, the distinction between capital versus current

maintenance remains for PPOs.

Effectiveness in Budget

Execution ↩︎

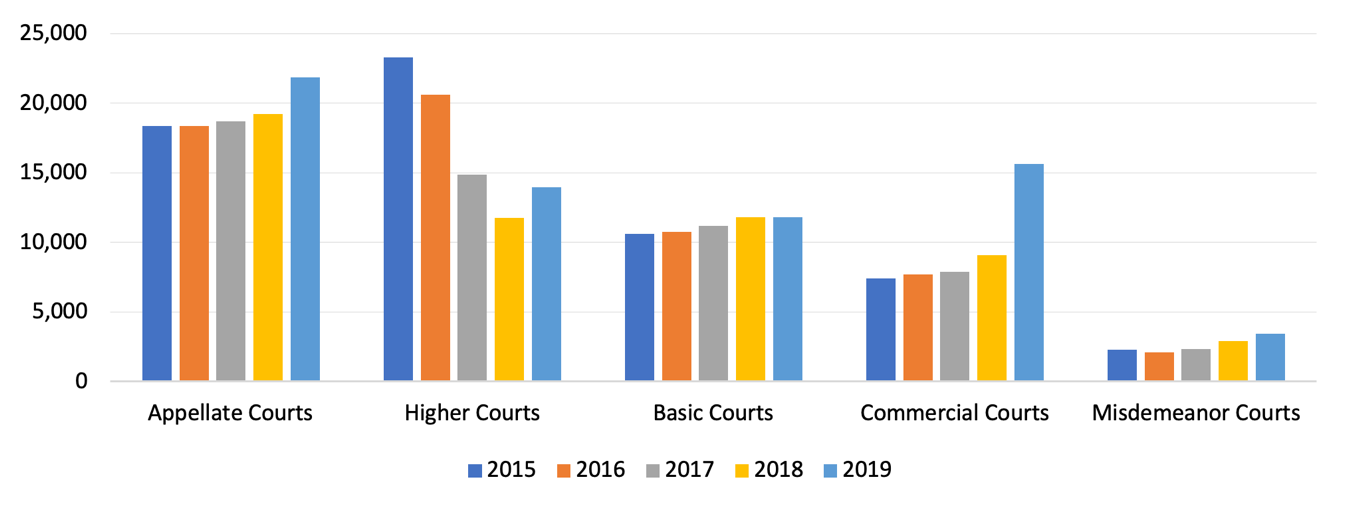

- The average cost for all active cases fluctuated from

2014-2018, with variances due to wage decreases in 2015 and 2016, ending

at RSD 9,038 in 2019. The average cost per

active case was RSD 10,515 in 2014, RSD 7,442 in 2015, RSD 7,136 in

2016, and RSD 7,393 in 2017, compared to RSD 8,016 in 2018. In 2018 and

2019, the cost per case rose due to an overall increase in court

budgetsand a relatively stable number of

active cases.

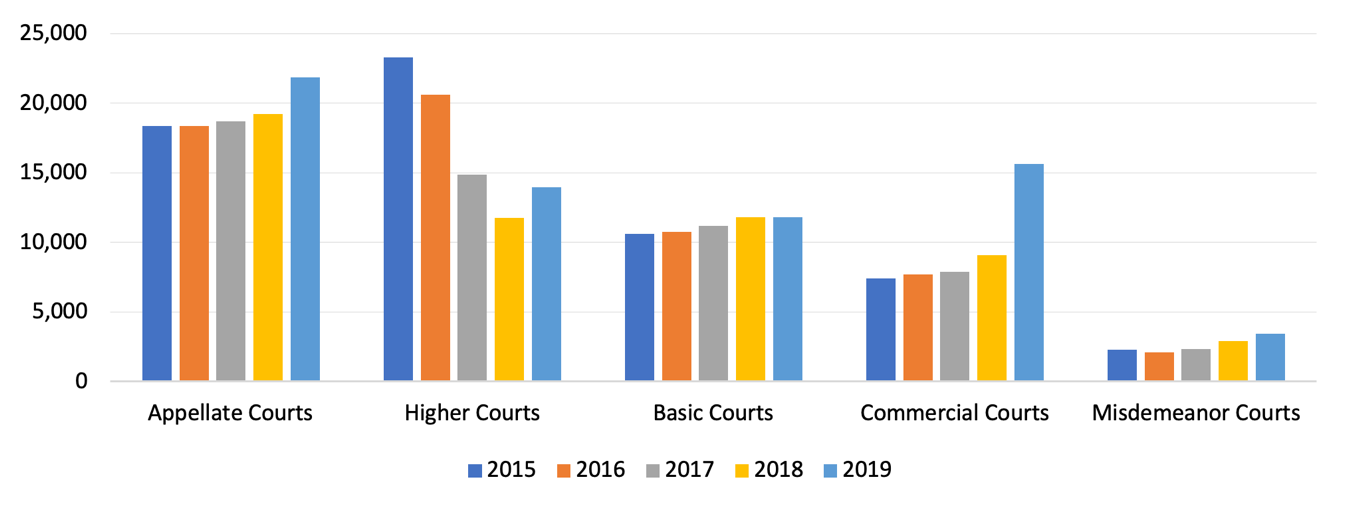

Figure 163: Aggregate cost per case per court category, 2014-2019

Source: Budget execution reports of judicial institutions and WB

calculations

- Almost all types of courts brought their average cost per

case down in the observed period. The primary sources of the

decrease for Higher and Basic Courts from 2014 to 2015 were the drop in

salaries and the drop in the cost of criminal cases once the

investigative responsibilities were transferred to PPOs. By 2018, as a

whole, the expenses of Higher Courts were less than 50 percent of their

expenses in 2014, based on the overall drop in expenditures and the

consistent increase in active (incoming plus unresolved) cases. Thus,

costs in the Higher Courts were not reduced because of efficiencies but

rather because of an increase in unresolved caseloads. Basic Courts

stabilized their expense per active case at RSD 11,000 from 2017

onwards. Their average number of cases was 916,000, without any

significant annual fluctuations.

- There were significant variations in the per-case

expenditures of individual courts within the same categories.

The expenditures for Higher Courts from 2014 to 2019 ranged from RSD

12,236 on average for HC Leskovac to as much as RSD 37,805 in HC

Negotin. For Basic Courts, the differences

were even higher. The minimum average expenditure per case was recorded

in BC Lebane (RSD 5,944), while BC Valjevo had the largest expenditure

level of RSD 21,192.

- In addition to possible inefficiencies within particular

institutions, different treatment of the split of investigation-related

expenses between the courts and PPO probably accounted for much of these

discrepancies. These differences are not being examined to

ensure consistency. Article 261 of the Criminal Code defines criminal

procedure costs as including “awards” to service providers (i.e.,

lawyers and expert witnesses) along with other costs, such as travel and

material costs (e.g. utilities, office supplies). The article also

specifies which expenses should be paid in advance of the investigation

process by “the institution managing the process”, but there were

different views of when the expenses should be paid and which

institution should pay. In some districts, PPOs paid the investigation

expenses they incurred regardless of whether an indictment was issued or

not. Other courts and PPOs, however, operated on the principle that once

an indictment was issued, the court became the “managing institution”

and was responsible for paying investigation expenses.

- Responsibility for examining these vast differences in

per-case costs has not been taken on by any governance

institution. The additional data are now available to evaluate

cost per case by type of institution should be utilized by MoJ and the

Councils to examine where efficiencies might be realized.

- The court system could not track cost-per-case trends in

the system or review other aspects of system performance as there are

inadequate systems to do so. Since there was no

interoperability between CMS and budget execution systems, it was not

possible to systematically link expenditure items to cases based on

their type, duration, number of parties involved, etc., and the HJC and

other authorities were severely hampered in their ability to spot and

address inefficiencies of different courts, or set standard ranges or

limits for expenditures for various case types or within different

levels of courts.

- The court system finally cut its arrears significantly in

2015 through a one-time intervention of allocating funds from the

budgetary reserve. Serbia’s Budget System Law prohibits

agencies from incurring liabilities that exceed current appropriations;

these liabilities are defined as arrears. Arrears represented 11.5

percent of total expenditure at the end of 2013 and only 1.5 percent at

the end of 2018. The assumption of responsibility for criminal

investigation expenses by PPOs was a major factor in the accumulation of

more arrears by the courts after the 2015 intervention.

Figure 164:Court system arrears, end of period, 2014-Q2 2020,

quarterly data

Source: Quarterly arrears reports of HJC

- Judicial authorities and the MoF also made less

successful attempts to tackle the issue of arrears and prevent them from

growing again. In 2015, the HJC issued an Act that intended to

have all courts in the system pay invoices for services rendered in the

criminal proceedings (the largest source of arrears in the system)

within 60 days. However, the requirement of payment within 60 days

already was part of the 2012 Law on Deadlines for Payments in Commercial

Transactions (LDPCT), so the 2015 Act effectively only clarified when

the 60-day period began. Greater monitoring of timely payments is not in

place.

- Lawyer and expert witness fees represented the largest

sources of arrears in the prosecutorial system and required more

examination and control. For both courts and PPOs, these fees

fell within ‘services,’ which also included costs for postal services,

fees for lay judges, arrest services, and compensation for lawyers and

expert witnesses providing their services during a trial.

Figure 165: Breakdown of arrears by type, end of period,

2014-2019

Source: Quarterly arrears reports of HJC

- The process of assuming commitments in courts and PPOs

generally was straightforward. Judges or prosecutors verified

service invoices for court proceedings and issued orders for payment of

the invoices. Once it was approved (and assuming the service provider

did not challenge the amount approved), the invoice was payable and

represented a liability of the court or PPO.

- The budget execution system did not require pre-approval

of commitments from budget authorities or the other procedures that

could have prevented the accumulation of excessive arrears. In

addition, the assumptions of commitments were not recorded against the

relevant appropriations, so there was no real-time tracking of the

accumulation of arrears.

- The enforced collection as a mechanism for settling

outstanding invoices was not used uniformly against all courts.

As confirmed by chief accountants of several courts and PPOs, individual

lawyers and expert witnesses make decisions about whether to force

collections. Lawyers and expert witnesses may hesitate to exercise this

right because they fear courts may cease engaging them. Although courts

and PPOs claim that lawyers are called for mandatory representation

according to an alphabetical list, in practice, there is nothing

stopping judges and prosecutors from calling a lawyer of their

preference. The same is true for expert witnesses. Such issue is more

pronounced in large courts and PPOs where the market for lawyers and

expert witnesses is abundant.

- One important feature of the LDPCT is it allowed the debt

of public sector entities to be settled through the enforced

collection. The introduction of enforcement agents, which

coincided with the LDPCT, set the stage for settling judicial

institutions’ debt through this mechanism. Interviews confirm that most

of the arrears come from debt to lawyers and expert witnesses combined

with benefits that accrue to lawyers during the process of enforced

collection, creating a network of incentives that boosts such practice.

There is an estimated 30 percent of unnecessary expenses on top of

original debt when an enforced collection is used to settle invoices.

These funds consist of various penalties and fees paid to the bailiff,

lawyer, NBS, court, etc.

- Commitments are recorded in two parallel ways – manually

(i.e. in notebooks or in MS Excel spreadsheets) and in the accounting

software used across the judicial system (ZUP). Both courts and

PPOs lack proper incentives to use ZUP since they report on their

financial operations on a cash basis. Reporting on arrears happens

through a separate procedure. Hence, it seems that the most accurate

records are kept manually. The lack of interoperability of these

‘sources’ of commitment and arrears records and BEX creates a world of

opportunities for excessive accumulation of uncovered commitments which

result in arrears growth.

- Although the stock of arrears is reported to HJC and SPC

quarterly, the accuracy and completeness of those figures are

questionable as it highly depends on the financial awareness and

responsibility of judicial staff. As a result, accounting

departments of courts and PPOs find out about a portion of their

unsettled bills only after they get paid through the enforced

collection. In practice, there are many cases when judges or prosecutors

never notify their accounting departments of an invoice or wait until

the end of the process to do that. A large portion of such invoices ends

up being settled through the enforced collection. Sometimes it even

happens that invoices are not settled regularly based on a verbal

agreement between the judge and service provider (i.e., lawyer or expert

witness) that it will be settled through enforced collection. It is

obvious that such examples of blunt disregard toward the financial

aspect of judicial function should be completely eliminated.

- The reduction in arrears seen in the 2014-2019 period is,

thus, partially due to an increase in them being settled instead through

the enforced collection, which is very costly and ineffective.

This only magnifies operational risks associated with arrears generation

as it complicates relationships with main service providers during

investigation and trial procedure. The FR team found out through

interviews with judges and prosecutors that, for instance, expert

witnesses, who are limited in number, are becoming reluctant to provide

their services because of the difficulty and uncertainty around settling

their invoices. These situations are more common in courts and PPOs

occupying smaller territories.

- Lack of data exchange (i.e. interoperability) between

accounting and financial systems on the one hand, and CMS on the other,

undermine efforts to obtain comprehensive, accurate, and reliable

financial information. If these systems were interconnected,

engaging a lawyer or expert witness would be an activity recorded in the

CMS, which would flow to the accounting system as an account payable.

From there, it would flow to the budget execution system, where such

commitment would be recorded and appropriate appropriation encumbrance

made. Although this is not easily attainable as it requires joint effort

from many parties (primarily MoF), achieving interoperability between

these platforms would prevent arrears accumulation and add significantly

to the quality of service delivery across the whole system.

- Budgets of judicial institutions should only be enhanced

once these institutions demonstrate awareness of the volume and type of

their financial operations. In other words, there has to be a

standard way of determining how much it costs to run a judicial

institution in Serbia with a certain number of judges/prosecutors

handling a certain number and types of cases. Only in these

circumstances can the requests for additional funds coming from judicial

institutions be assessed and decided properly. Increasing the budgets of

courts and PPOs linearly or continuing the practice of settling their

debts at year-end with a one-off outlay from the budget reserve is not a

solution. In fact, this represents a ‘reward’ for those who act

irresponsibly and assume financial commitments beyond what they are

allowed to. On the other hand, the more prudent institutions are

discouraged from continuing to act responsibly.

Recommendations and Next

Steps ↩︎

Examples of recommendations that inspired some reform activity over

the past seven years are: i) regular reporting on arrears and settling

existing levels of arrears, and ii) introduction of a binding

interpretation of financial responsibilities for the costs of

investigations. The majority of 2014 Functional Review recommendations

in data management, court fees collection, commitment and arrears

management, in-year budget management, and financial responsibilities

within the judicial system have not been implemented. Although there is

clear evidence of efforts made to address the issues of budgetary

responsibility and arrears management, these efforts were far from

sufficient to resolve them.

Recommendation 1: Improve the financial management

infrastructure and institutional framework to enhance operations,

improve transparency and efficiency, and add to the budgetary

independence of judicial institutions.

- Increase awareness of judges and prosecutors about budgetary

matters and public financial management in general. This is the key to

achieving better cost-effectiveness across both court and prosecutorial

systems. (HJC, SPC – short-term)

- Simplify the management structure of the judicial system budget.

This can be achieved by transferring the budget responsibilities of MOJ

to HJC and SPC, with the exception of capital budget management, which

should remain with MOJ because of: (1) MOJ’s greater capacity related to

procurement and (2) the challenge of allocating such costs and

responsibilities over multiple institutions occupying the same facility.

(MOJ, SPC, HJC, MOF – short-term)

- Introduce a standardized Budget Preparation Management tool

(i.e., software) across the entire judicial system, which is fully

compatible with the existing BMPIS used by MOF. (MOJ, SPC, HJC, MOF -

medium-term)

- Further strengthen the capacity to manage capital investments. In

order to maintain and improve current capital expenditure levels, MOJ’s

staff skill set needs to be enhanced in the following areas: project

preparation, appraisal and selection, and management and monitoring of

project implementation. Formulate and introduce project selection and

prioritization methodology. (MOJ – medium-term)

Recommendation 2: Strengthen the budget execution process to

enhance financial data integrity and completeness, improve current-year

monitoring capacities, and ensure standardization and consistency in

budget execution.

- Clarify the financial responsibilities of courts versus PPOs

within the criminal investigation procedure by modifying article 261 of

the Criminal Code and formulating accompanying bylaws to further clarify

the issue and ensure consistency in costing. (HJC, SPC –

short-term)

- Optimize and standardize all elements of invoice processing

(i.e., define precisely the document flow) across judicial institutions

to avoid excessive arrears accumulation and eliminate invoice settlement

through the enforced collection. (HJC, SPC – medium-term)

- Ensure accuracy and completeness of accounting records within

ZUP. This would eliminate the need for keeping parallel manual records

of various accounting categories for different purposes. (Courts, PPOs,

HJC, SPC, MOJ – short-term)

- Increase the insight of MOJ, SPC, and HJC into aggregate

accounting categories in ZUP to enhancetheir in-year analytical focus

and inform budgetary policy adjustment/formulation. (MOJ, HJC, SPC -

medium-term)

- Enable data exchange (i.e., enable formulation and transfer of

payment request and retrieval of transaction settlement information)

between ZUP and the budget execution system. (MOJ, HJC, SPC –

medium-term).

- Gradually reduce the “buffers” (i.e., reserves) from

appropriation management. Increase the financial responsibility of

judicial institutions by allocating the full amount of their annual

appropriations at the beginning of the year. (HJC, SPC –

medium-term)

- Increase transparency of allocation of court fees across courts

and PPOs. The subjectivity in distributing the shares of court fees by

MOJ and HJC should be eliminated through the introduction of a coherent

and comprehensive allocation methodology in line with the Law on Court

Fees. (MOJ, HJC – medium-term)

Recommendation 3: Strengthen the budget preparation process.

Since budgets of judicial system segments are not based on

performance-related criteria, they cannot be used to assess performance,

which is the cornerstone of responsible budget management. The following

recommendations are designed to: i) enable judicial authorities to

determine a credible baseline budget, ii) formulate their budgets based

on case-related performance criteria, and iii) measure performance in

order to inform decision-making based on reliable data.

- Ensure interoperability between CMS, the budget execution system,

and the budget preparation system. Ensuring data exchange between them

is an instrumental precondition for introducing performance-based

budgeting. (HJC, SPC, MOJ – medium-term)

- Introduce case-costing methodology. This methodology should be

able to answer the question of what is an expected range of costs for

different types of cases and thus feed into the budget formulation

process. (HJC, SPC – medium-term)

- Introduce performance-based budgeting. Develop a baseline budget

based on the data retrieved from the CMS and the case-costing

methodology. Analysis of the budget will subsequently enable

cost-effectiveness and free up resources for other purposes. (HJC, SPC –

medium-term)

- As a transitional measure, engage with MOF to gradually increase

the investigation services budget. At present, arrears are settled by

one-off increases in judicial budgets at the end of the year. This

amount should be made available at the beginning of the year to avoid

unnecessary fees and penalties paid by courts and PPOs in the process of

enforced collection. (SPC, MOF – short-term)