Public Prosecutors’ Offices

Efficiency,

Timeliness, and Productivity of Prosecutors’ Offices

- Serbia’s system of prosecution has undergone substantial

change since an adversarial system was introduced in 2013, but

performance measurement for Serbia’s prosecutors is too basic to

evaluate the impact of these reforms or the overall performance

of prosecutors’ offices. Prosecutors still lack support on using

performance measurement data to improve case management, develop

successful funding requests, foster public support, and respond to

criticism.

- Available data for prosecutorial services still was far

less extensive than it was for courts, and the data that was reported

was of limited use because of the collection methods and

formats. There was no unified electronic case management system

for the prosecutorial system in place by the end of 2019. Thus, the

preparation of those reports depended highly on manual data collection

and individual interpretation, which made the reports prone to

inconsistencies and inaccuracies.

- Serbian PPOs generally processed cases in a more timely

manner in 2018 and 2019 compared to previous years due to an increase of

nearly 25percent between 2016 and 2019 in the number of public

prosecutors working on cases. As a result, caseloads per

prosecutor decreased by 25 percent in Basic PPOs, by 33 percent in

Higher PPOs, and by 18 percent in Appellate PPOs.

- In 2017, the total number of PPO cases carried forward

from one year to the next also started decreasing after three years of

consistent increases. Cases carried forward from one year to

the next are characterized as backlogs. Appellate PPOs had very few

carried-forward cases. The number of carried-over cases in Basic PPOs

grew until 2016-2017, then declined. However, the number of

carried-forward cases in Higher PPOs grew every year between 2014 and

2019.

- Related to backlogs, clearance rates consistently

increased from 2014 through 2019.

The improvement in clearance rates for Basic PPOs was notable. The

average clearance rates for Higher PPOs were over 90 percent, but there

was an increasing trend of backlogs. The four Appellate PPOs each had

clearance rates of 100 percent over the six years from 2014 through

2019.

- Clearance rates do not indicate whether the oldest and/or

most complicated cases were concluded within reasonable

timeframes. The pressure to resolve more cases as quickly as

possible may mean that older and more difficult cases continue to age.

This result undercuts public confidence in prosecutors and the judicial

system overall, especially considering the impending statute of

limitations expiration.

- There is still no concrete data on the age structure of

pending cases. Also, the

information on aging cases would be very different if ‘unknown

perpetrators cases,’ also known as KTN cases, were included.

- There is room for improvement in the congestion ratio, a

measure of delay that addresses the ratio of resolved to unresolved

cases at the end of a year. Although they were improving, Basic

PPOs continued to have the highest congestion ratios among the three PPO

categories, with results two to six times higher than those of Higher

PPOs. There was no congestion in Appellate PPOs.

- Time to disposition is not tracked by Serbian

PPOs. Estimates suggest that disposition times vary greatly,

from less than a month to more than a year, depending on the level and

location of PPOs. Disposition times are longer in Basic PPOs, but some

Higher PPOs need improvement as well.

- Across all PPO types, average dispositions per prosecutor

were very similar to the trends for caseloads per prosecutor.

From 2014 to 2019, there was an increase of 10 percent for average

dispositions per prosecutor in Basic PPOs, and decreases in Higher and

Appellate PPOs by 29 and 17 percent, respectively.

- Because the responsibility for investigation has been

transferred from courts to PPOs, there is a concern among prosecutors as

to whether they have sufficient resources to process cases

efficiently. The increase in prosecutors’ responsibilities must

be followed by adequate resource allocation, which was not the case in

Serbia.

- There are significant and unexplained differences in the

performance of different PPOs at the same level. Appellate

PPOs, overall, are the most efficient of the three levels of PPOs. This

suggest that, on average, their resources are matched appropriately with

the demands for their services. Others specialized PPOs and specialized

departments in Serbia faced performance issues.

Introduction ↩︎

- Caseload numbers for Serbian PPOs generally were higher

than caseload numbers for the corresponding courts since PPOs identify

their cases by individual perpetrators

while courts, as a rule, identified their cases by the event,

which forms the basis of the charges and which could have involved many

defendants. The FR 2014 identified efficiency in the delivery

of prosecution services as a concern, but a lack of data inhibited more

detailed analysis. Despite the shortcomings in data availability that

still exist, enhanced data availability in this FR provides much more

insight to prosecution services than it was possible in FR 2014.

- Due to the lack of more extensive data that covers all of

2014 to 2019, this report has focused on criminal complaints (adult,

juvenile, and legal persons) and commercial

offenses. Criminal complaints against

unknown perpetrators are shown separately due to a substantial pending

stock accumulated over the years that would distort the overall figures.

Other specific case types are also analyzed separately and excluded from

the totals.

- Appellate PPOs data for 2014 to 2019 were collected

specifically for this report from the PPOs via the RRPO and the

SPC. The data includes the following case types or case stages:

second- and third-instance criminal complaints, “various criminal

cases”, complaints by injured persons, indictments, “corruption criminal

offenses” and other cases.

- Due to the nature of their caseloads, the work of

specialized PPOs has been analyzed separately in this FR.

Although the Special Prosecutor’s Office for War Crimes and the Special

Prosecutor’s Office for Organized Crime handle relatively few cases

compared to other Higher PPOs, their cases generally are complex and

generate significant public interest. The higher caseloads of the

specialized department for high-tech crime and the specialized

departments to combat corruption also are examined separately.

Caseloads and Workloads ↩︎

Overall Demand for

Prosecutors’ Services ↩︎

- As was true for the earlier FRs, overall demand for

prosecutorial services is assessed through caseloads and workloads,

with ‘caseload’ defined as the number of incoming cases

for a given year and ‘workload’ as the sum of the number of incoming and

pending cases for a given year.

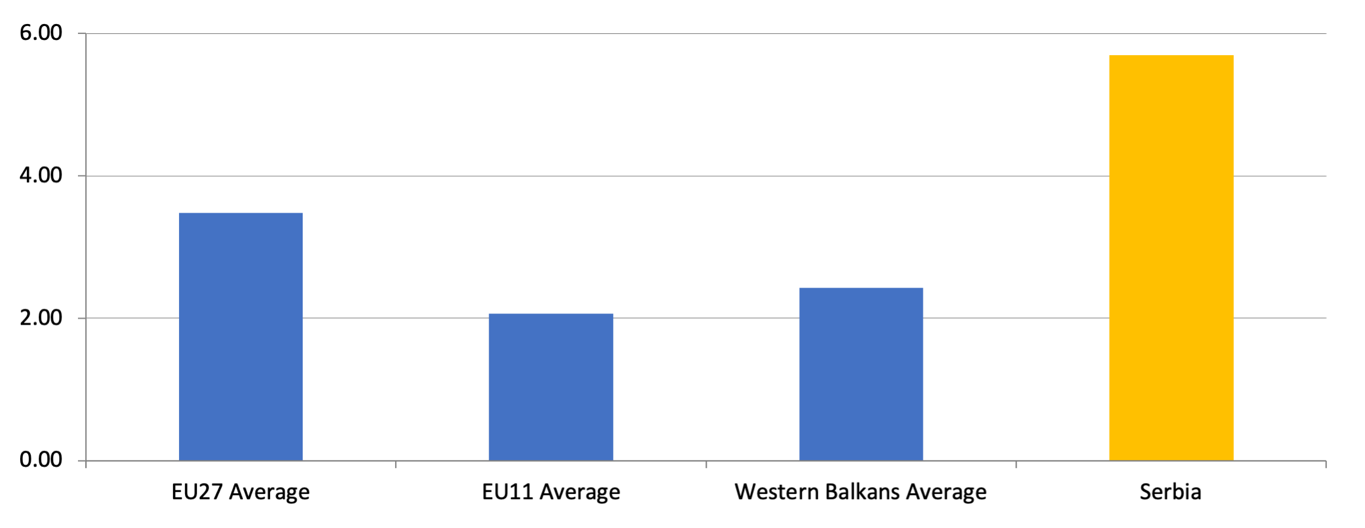

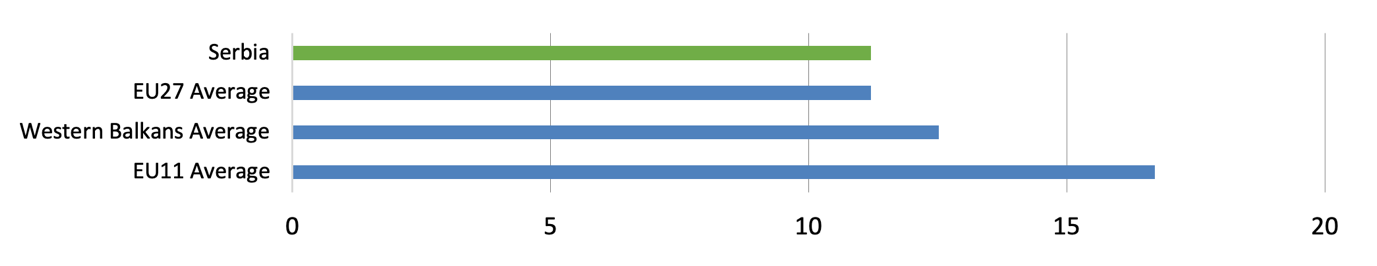

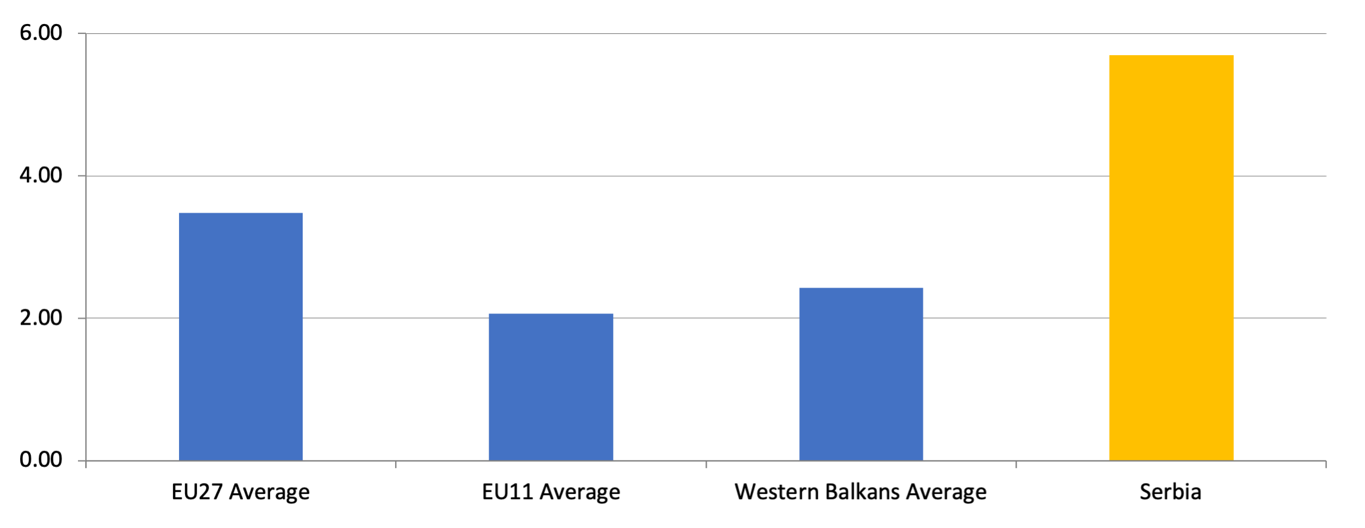

- According to the CEPEJ 2020 report, based on 2018 data,

the incoming caseloads of prosecutors in Serbia were significantly

higher than in the EU27, the EU11 Member States, and the Western

Balkans. Serbian prosecutors in 2018

received 5.70 cases per 100 inhabitants, while the average of EU27 was

3.48. The EU11 Member States and Serbia’s Western Balkans peers reported

2.06 and 2.43 received cases per 100 inhabitants, respectively. See Figure 55 below.

Figure 55: Number of Cases Received by Public Prosecutors per 100

Inhabitants

Source: CEPEJ 2020 report (2018 data)

- The incoming caseloads of prosecutors in 2018, as

calculated by CEPEJ, increased by three and a half times compared to

2016, primarily due to the changes in the reporting methodology, i.e.,

the addition of case types to Serbia’s reported numbers.

Previously, the number of received cases per 100 inhabitants had been

decreasing; in 2014, it decreased from 3.15 to 2.77 and 1.61 in 2016. As

described earlier in this analysis, unknown perpetrators and various

other case types were introduced to cases reported to CEPEJ in Serbia’s

data for 2018. It also is not clear from the CEPEJ report what type of

cases may be included in the statistics provided from every country –

for instance, Croatia does not include unknown perpetrators in the

reported number of cases handled by its prosecutors. Serbia’s high

figures also caused the Western Balkans average based on 2018 to rise,

i.e., without Serbia’s numbers, the Western Balkans average would have

been 1.61 cases received by public prosecutors per 100

inhabitants.

Caseloads of PPOs ↩︎

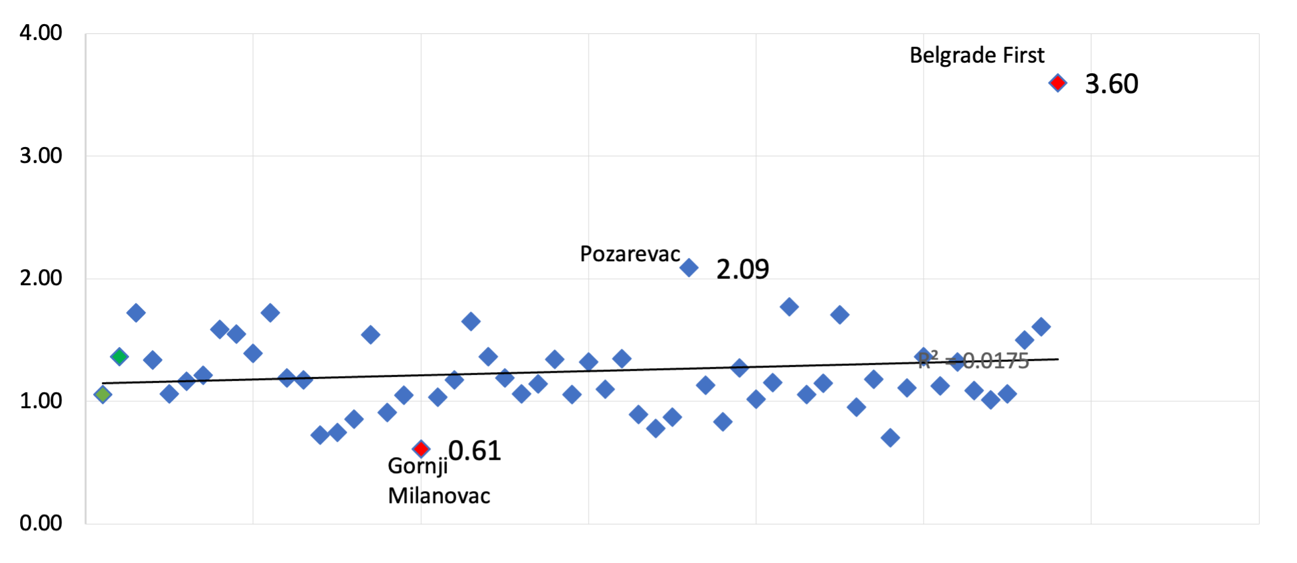

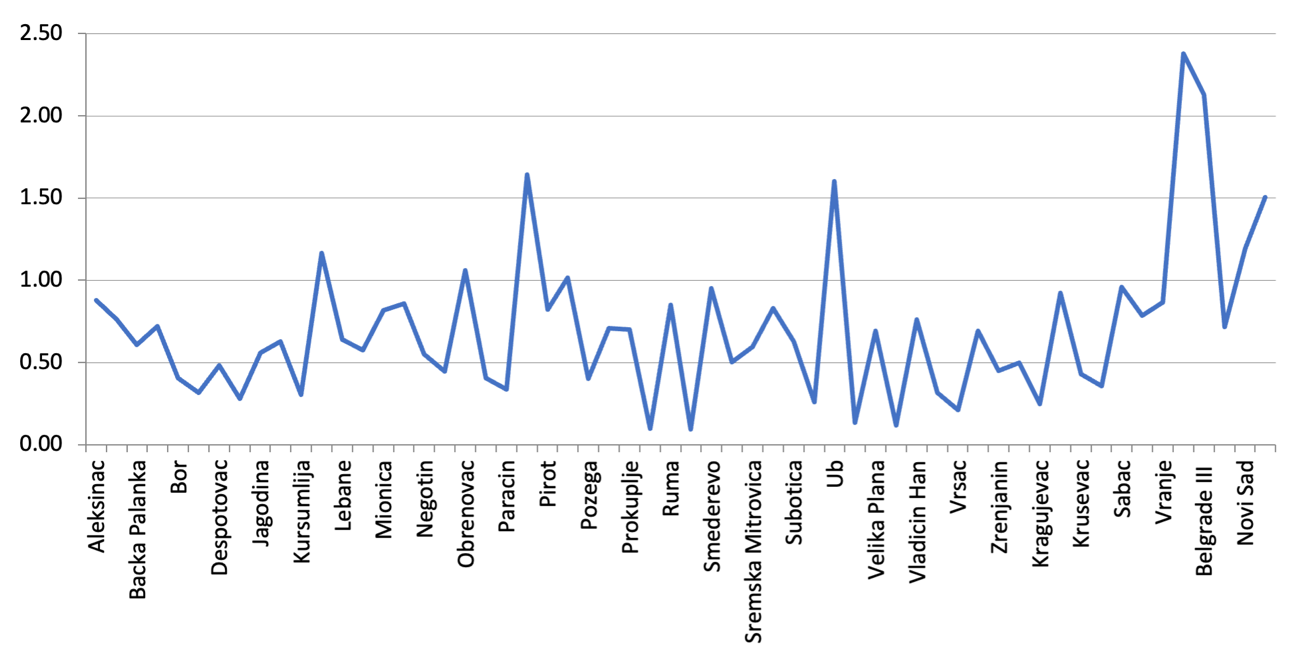

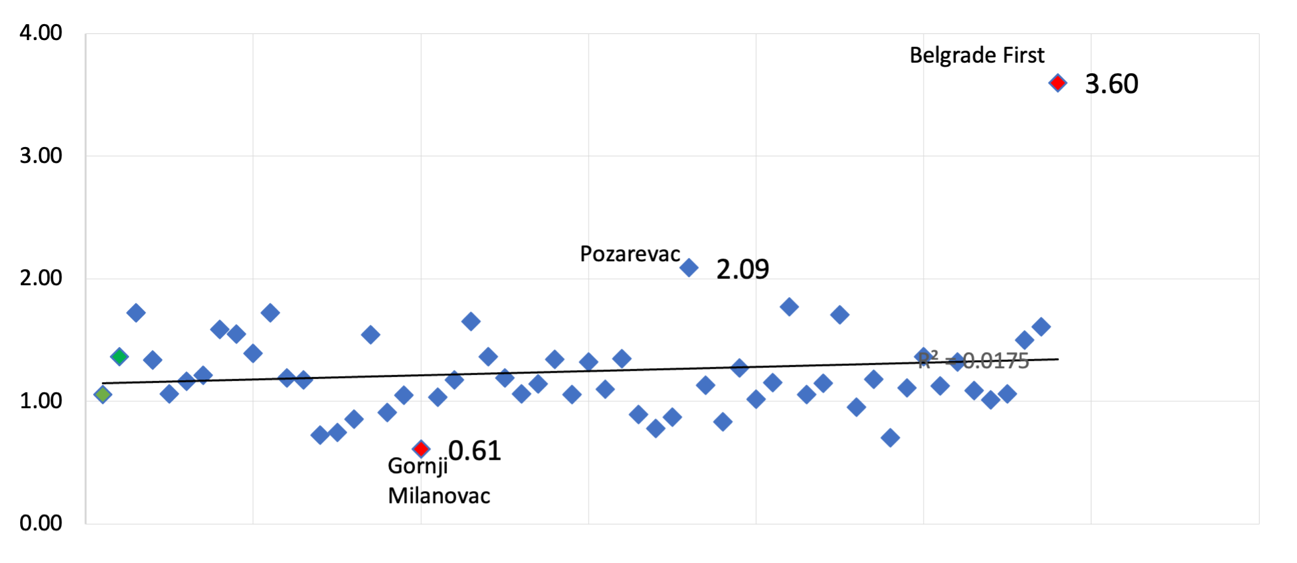

- PPOs in the country’s large urban areas did not always

have the largest relative caseloads, and there also was no concentration

of incoming cases in any particular region or for PPOs of any particular

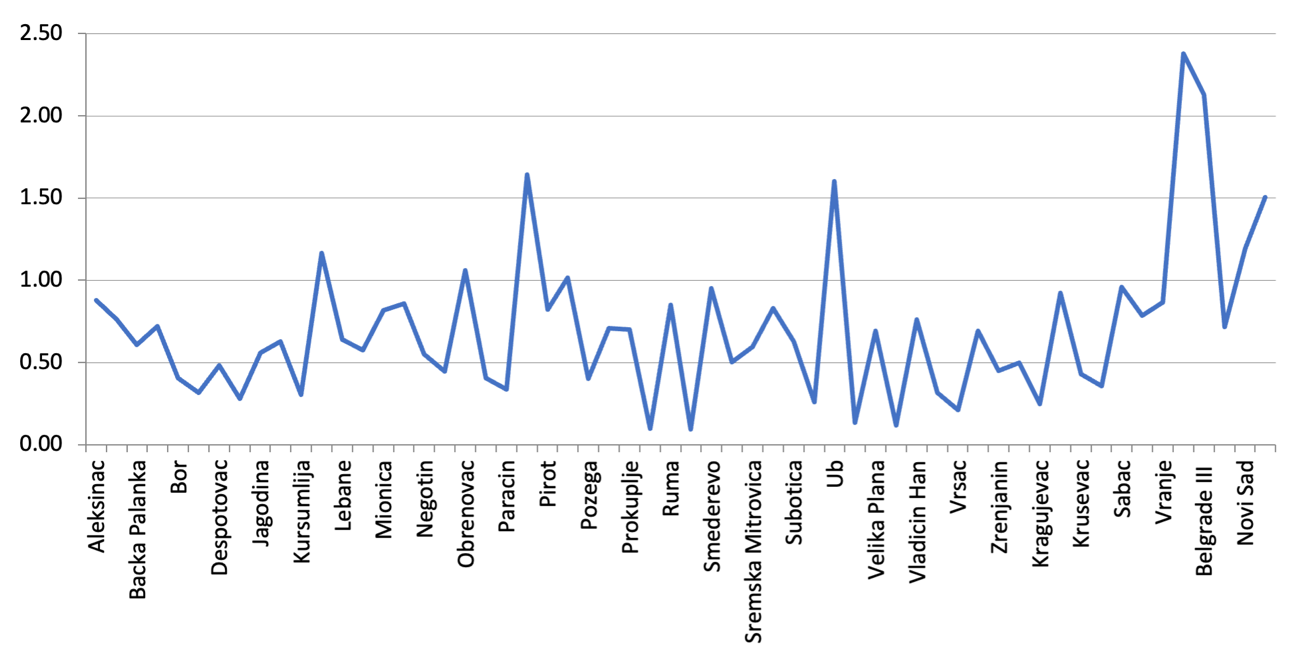

size. These conclusions are presented in Figure 56, below. For

instance, in 2014, the small Basic PPO in Senta had the highest relative

caseload, with 4.47 incoming cases per 100 inhabitants, while In 2015,

the highest caseload of 2.51 cases per 100 inhabitants was recorded in

the medium-sized Basic PPO in Vranje.

Serbia’s largest Basic PPO, the First Basic PPO in Belgrade, came in only sixth with 2.20

incoming cases per 100 inhabitants in 2014 and fifth with 2.21 in 2015,

but it held first place in terms of incoming cases per 100 inhabitants

from 2016 through 2019. Conversely, in 2019 the Second and Third Basic

PPOs in Belgrade, each with an area of roughly 500,000 inhabitants,

recorded only 2.12 and 2.33 incoming cases per 100 inhabitants,

respectively. The Basic PPO in Novi Sad, Serbia’s second-largest city,

was 19th in 2019, with 1.34 received cases per 100

inhabitants.

Figure 56: Incoming Caseloads of Prosecutors per 100 Inhabitants in

Basic PPOs in 2019

Source: RPPO Annual Report 2019 and Population Census

2011

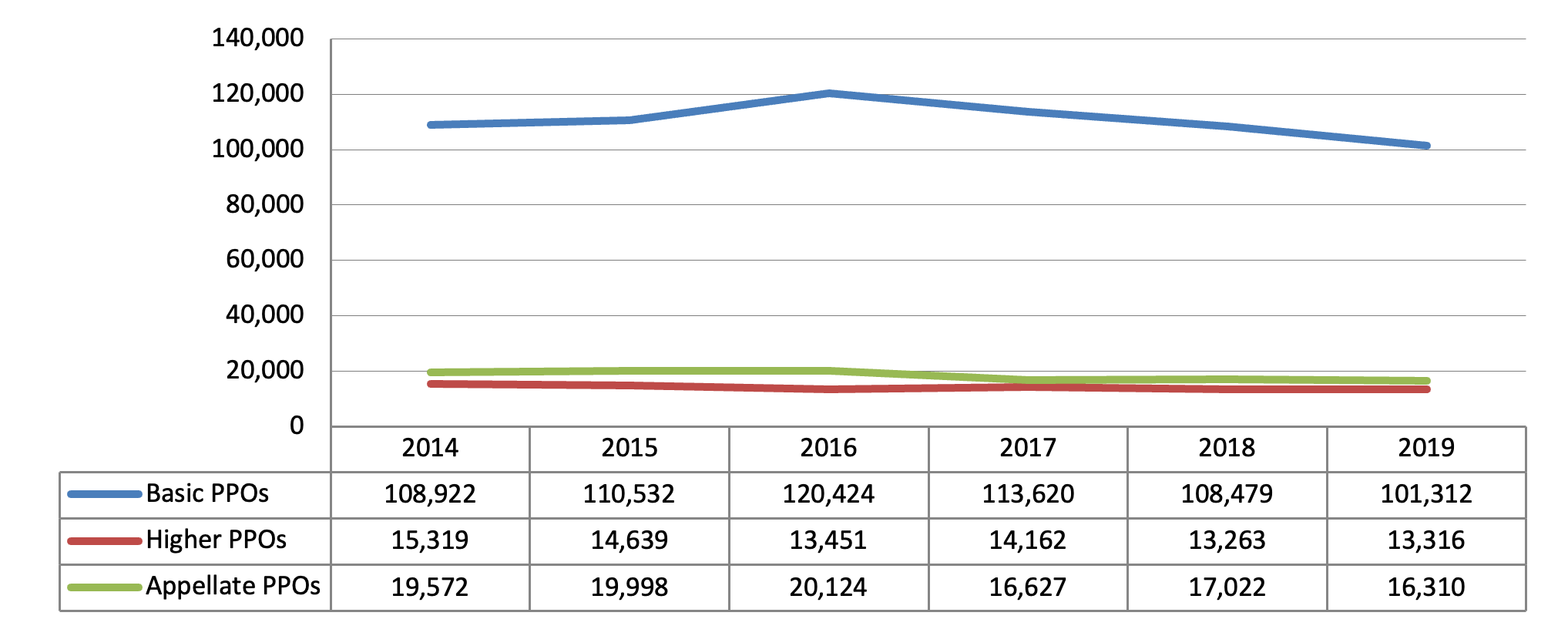

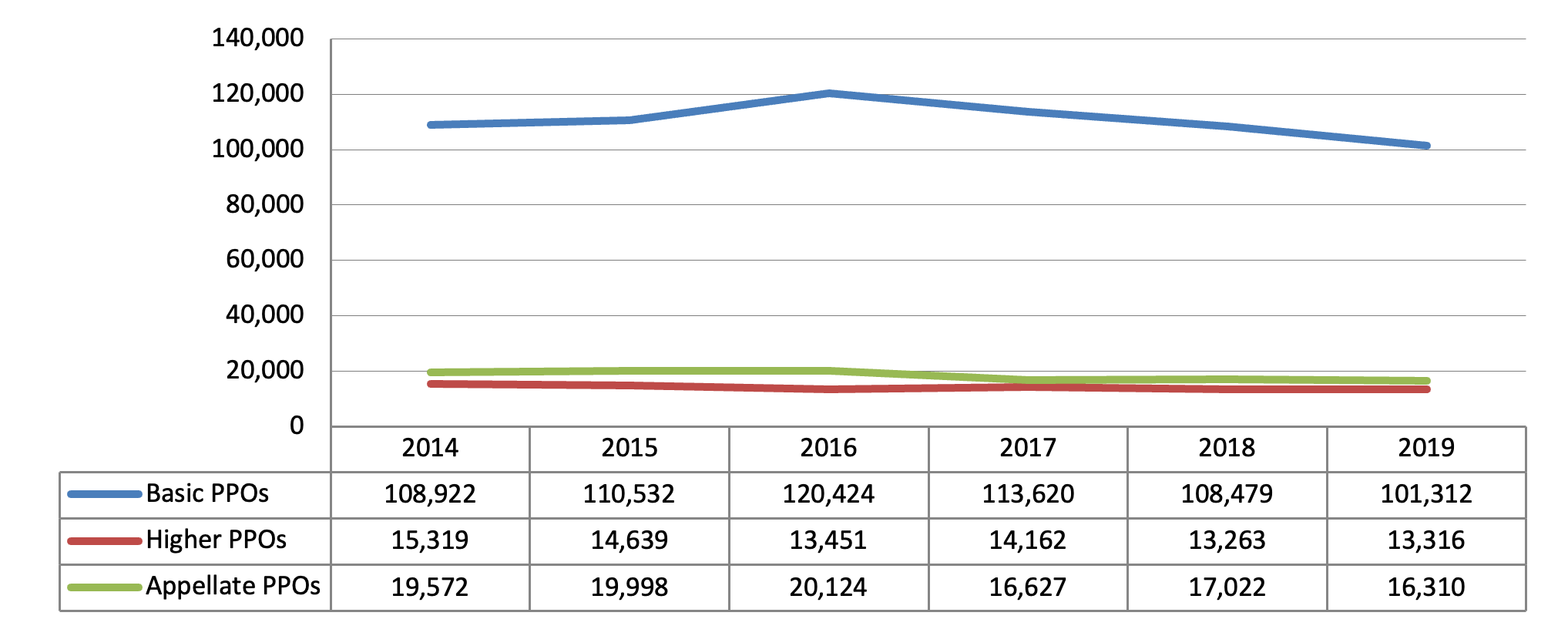

- In 2019, Basic, Higher, and Appellate PPOs received

130,938 new cases, which represented a seven percent increase in the

caseload from 2014. Seventy-seven percent of the 2019 total, or

101,312 cases, were received by Basic PPOs. This compared to 76 percent

in 2014. Higher PPOs received one-tenth or 13,316 cases in 2019,

compared to 11 percent in 2014. Just over one-tenth of the total, or

16,310 cases, were received by the Appellate PPOs, compared to 14

percent in 2014. See Figure 57.

Figure 57: Received Cases in Basic, Higher and Appellate PPOs from

2014 to 2019

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014 – 2019 and Appellate PPOs

Data

- The seven percent increase for all PPOs from 2014 to 2016

was driven by the increased caseload received by Basic PPOs, which grew

by 11 percent or 11,502 cases. In contrast, the caseloads of

Higher PPOs decreased by 1,868 or 12 percent during the same period. The

largest share of the cases received in 2016 were those involving adult

and juvenile criminal cases in Basic and Higher PPOs (68 percent of the

153,999 cases), followed by commercial offenses (14 percent), and the

0.13 percent involving legal persons

cases. Thirteen percent of the total incoming caseload was handled by

the Appellate PPOs, which was an increase of three percent from 2014.

From 2016 to 2019, the incoming caseload remained stable in Higher PPOs,

while a decrease of 16 percent and 19 percent was witnessed in the Basic

and Appellate PPOs, respectively. In 2020, Basic PPOs received 88,744

cases or 12 percent fewer cases than in 2019. Higher PPOs received

11,128 cases, a decline of 16 percent over the previous year. Both were

caused by declines in the most significant case types: criminal cases

and commercial offenses in Basic PPOs and criminal cases and juvenile

cases in Higher PPOs. Legal persons cases continued to occupy a

negligible portion of the PPOs caseloads in 2020.

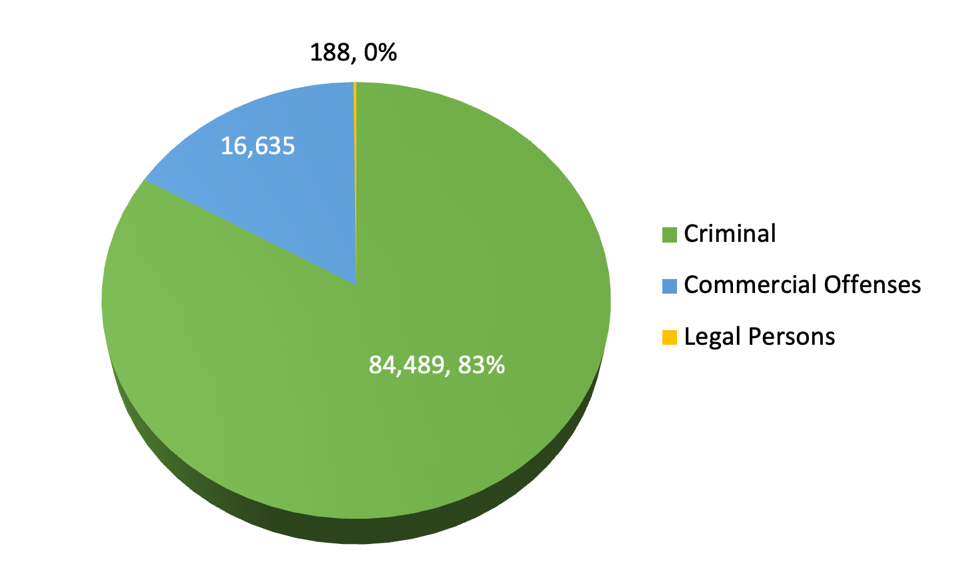

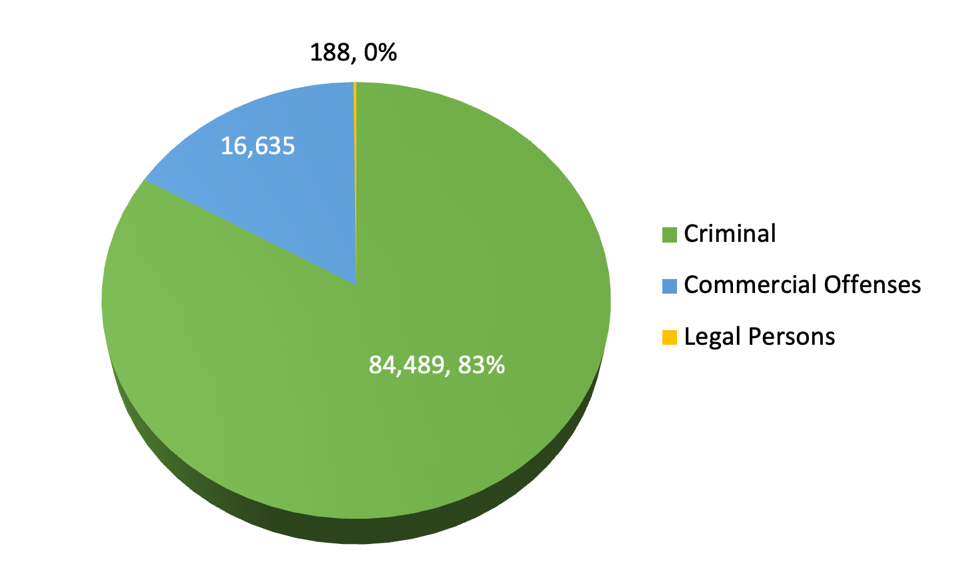

- The largest share of the incoming caseload in the Basic

PPOs in 2019 were criminal complaints, 88,489 thousand or 83

percent. Commercial offenses represented 16 percent of these

and the legal persons were 0,19 percent, as shown by Figure 58.

Figure 58: Received Cases in Basic PPOs by Case Type in 2019

Source: RPPO Annual Report 2019

Box 17: The continuing problems posed

by the “various criminal cases,” included in the KTR registry

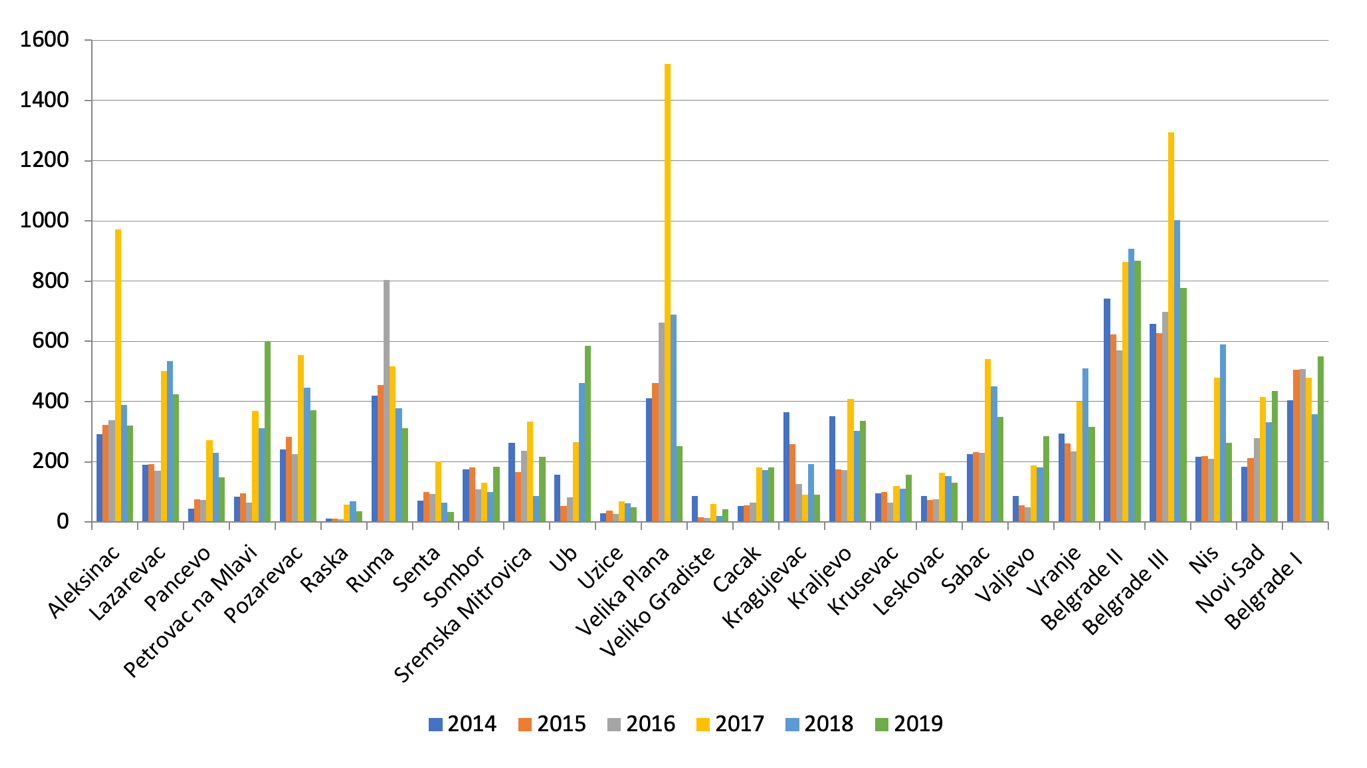

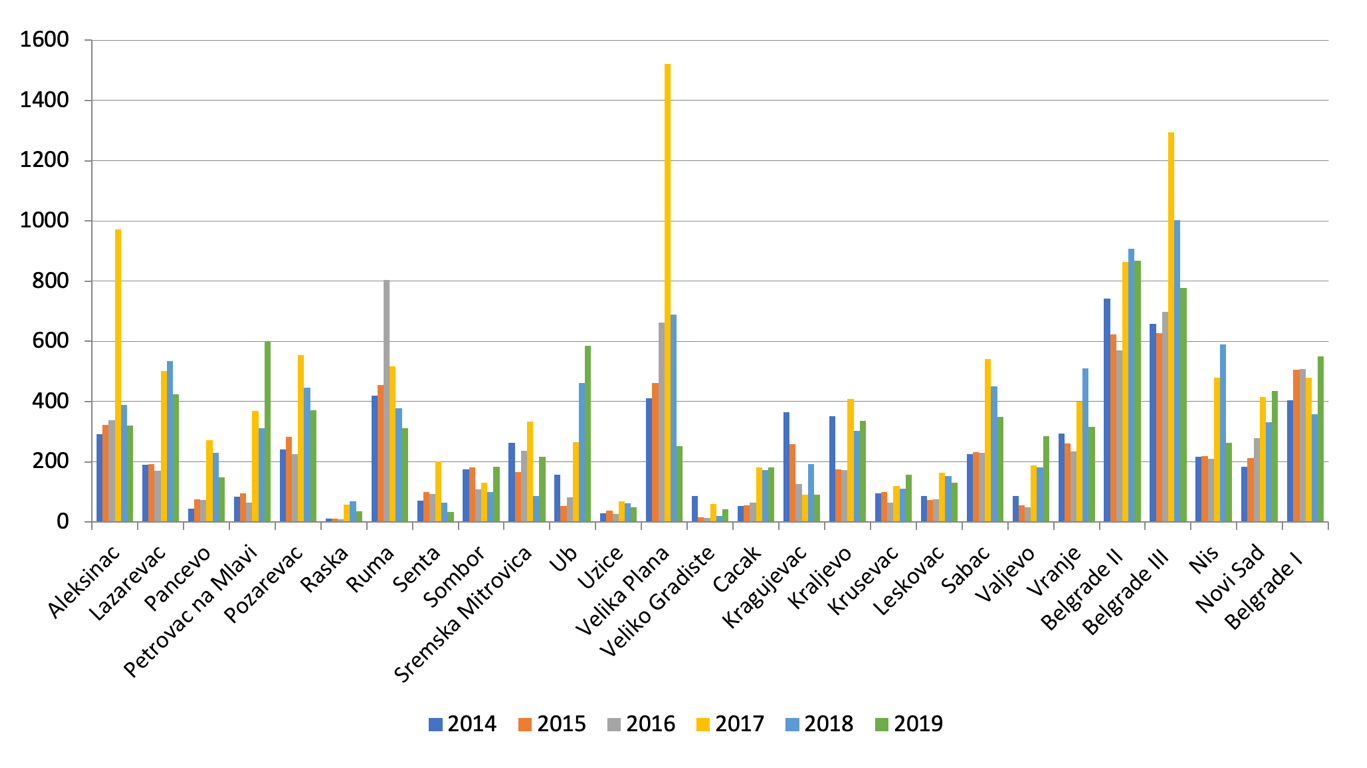

- Available data did not explain the most significant

caseload variations for individual Basic PPOs, and there was no analysis

by the RRPO or the SPC made available to the FR team of the reasons for

these differences. In general, the overall

number of received cases increased each year for until 2016 and then

stabilized, but there were exceptions. For example, the most significant

yearly variation – an increase of 206 percent – was reported for the

Basic PPO in Obrenovac in 2015 due to a jump in the number of criminal

complaints. More specifically, that Basic PPO received 574 criminal

complaints in 2014, 1,757 in 2015, 1,182 in 2016, 796 in 2017, 646 in

2018 and 798 in 2019.

- The caseloads for Higher PPOs declined by 13 percent

overall from 2014 to 2019, but the FR team also was not privy to any

official analysis of the reasons for this phenomenon. In

absolute numbers, 14 Higher PPOs saw an increase in their caseloads by a

total of 354 cases, while the remaining 11 Higher PPO caseloads

decreased by a total of 2,152 cases. As shown in Figure 59 below, 14 of

25 Higher PPOs received more cases in 2019 than in 2018. The highest

increases were recorded in the Higher PPOs in Jagodina, Novi Pazar,

Cacak, and Leskovac, by 41, 39, 29, and 18 percent, respectively.

Conversely, the most significant decreases were more modest, by 16

percent in Kraljevo, 15 percent in Novi Sad, 13 percent in Nis, and 12

percent in Sombor.

Figure 59: Received Cases in Higher PPOs from 2014 to 2019

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014 – 2019

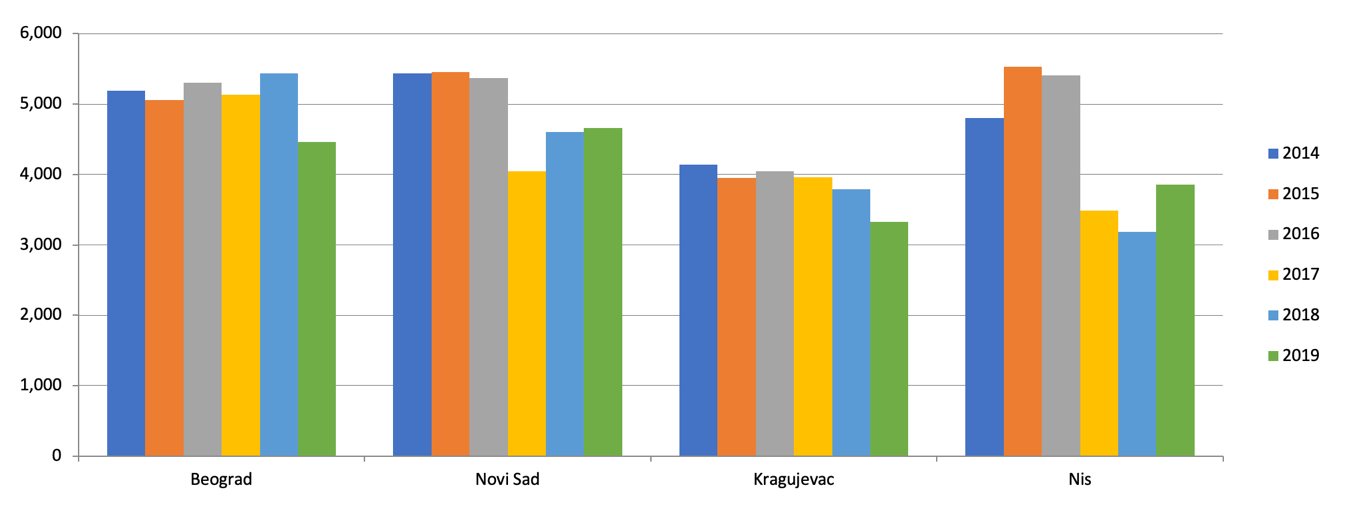

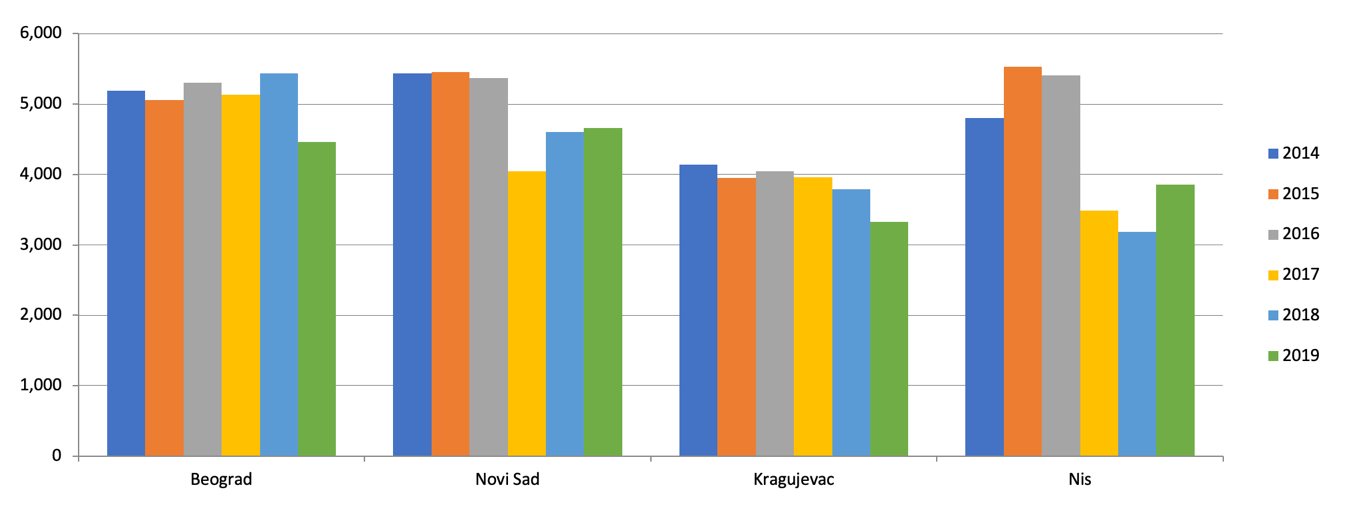

- From 2014 to 2019, the total appellate caseload fell by

17 percent and included most case types, but data did not reveal any

specific reason(s) for this drop. The marked decline began in

2017 when all Appellate PPOs received fewer cases, but the most

significant changes were recorded by the Appellate PPOs in Nis (with a

35 percent decline and 1,920 few cases) and Novi Sad (25 percent and

1,318 cases). By 2019, the Appellate PPOs in Belgrade and Kragujevac had

joined the trend; Belgrade had 18 percent fewer cases than it had in

2018, and Kragujevac had 12 percent fewer. In Novi Sad, the incoming

caseload remained stable from 2018 to 2019, while in Nis, it grew by 21

percent. See Figure 60 below.

Figure 60: Received Cases in Appellate PPOs from 2014 to 2019

Source: Appellate PPOs Data

Box 18: Second and Third Instance Prosecution Cases

Prosecutors’ Services by Case

Type ↩︎

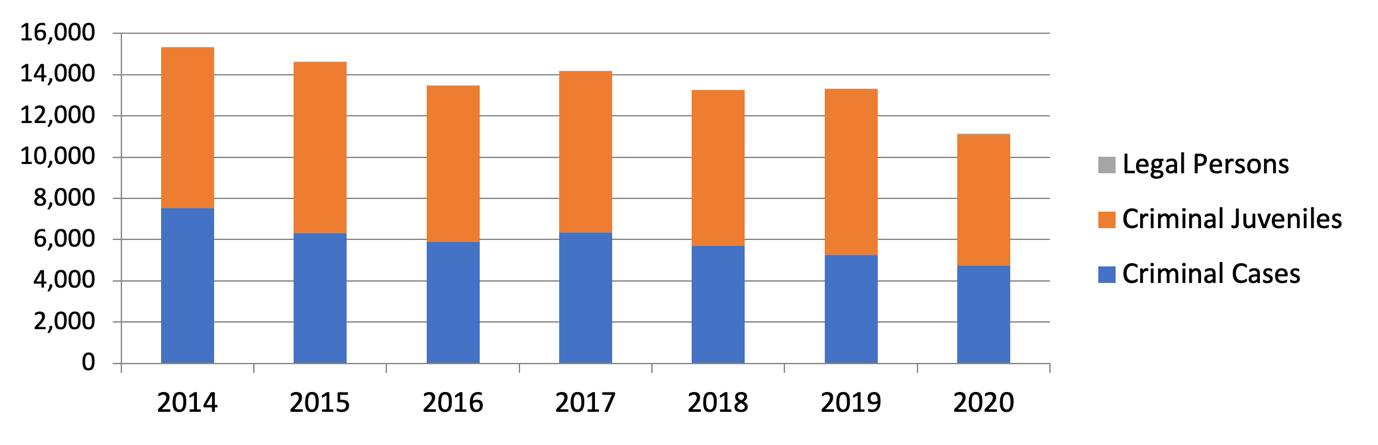

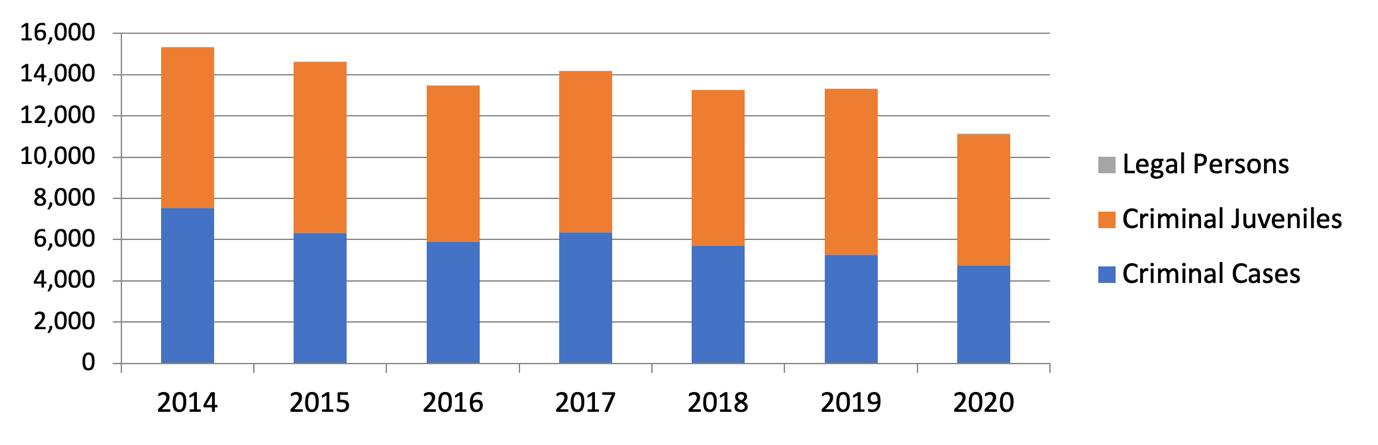

- In Higher PPOs, from 2014 to 2019, caseloads of criminal

cases against adult defendants decreased by 30 percent while the

criminal, and juvenile cases increased by three percent. There

was an increase from seven to 18 received cases for the category of

legal persons during the same period. In 2020, Higher PPOs received ten

percent fewer criminal cases and 21 percent fewer juvenile cases than in

the previous year, as shown in Figure 61 below. There were 43 newly

received legal persons cases in 2020, exclusively due to Higher PPO in

Belgrade incoming stock.

Figure 61: Received Cases in Higher PPOs by Case Type from 2014 to

2020

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014 – 2020

- A 10-fold increase in the caseloads for commercial

offenses from 2015 to 2016 was triggered by the implementation of the

new Accounting Act and caused a

bottleneck in PPOs that lasted through 2019. The Accounting Act

was passed and took effect before prosecutors could develop procedures

to handle these cases or seek the additional resources they needed to

handle them. The number of received commercial offense cases jumped from

1,732 in 2015 to 21,178 in 2016 and still stood at 23,321 in 2017,

19,900 in 2018, and 16,635 cases and 2019. A new Accounting Act entered into force on 1 January

2020 but it did not contain any significant changes related to

commercial offenses.

Workloads of PPOs ↩︎

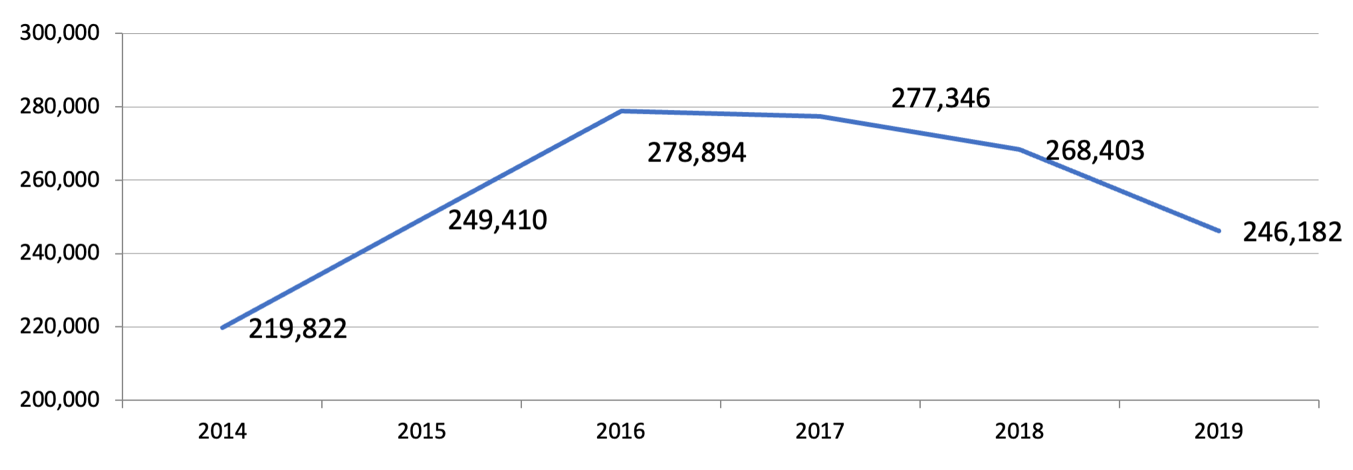

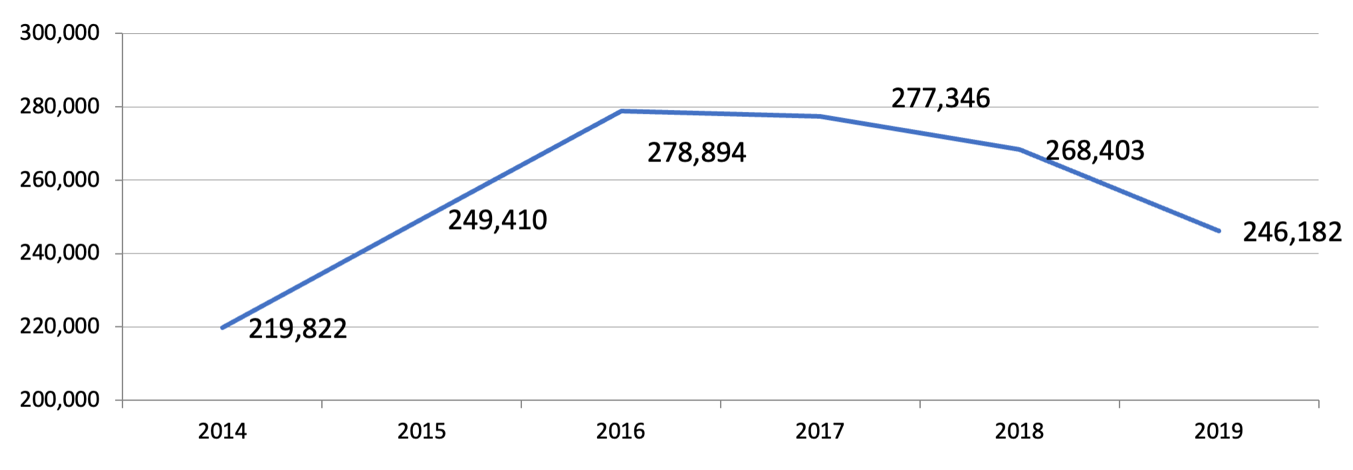

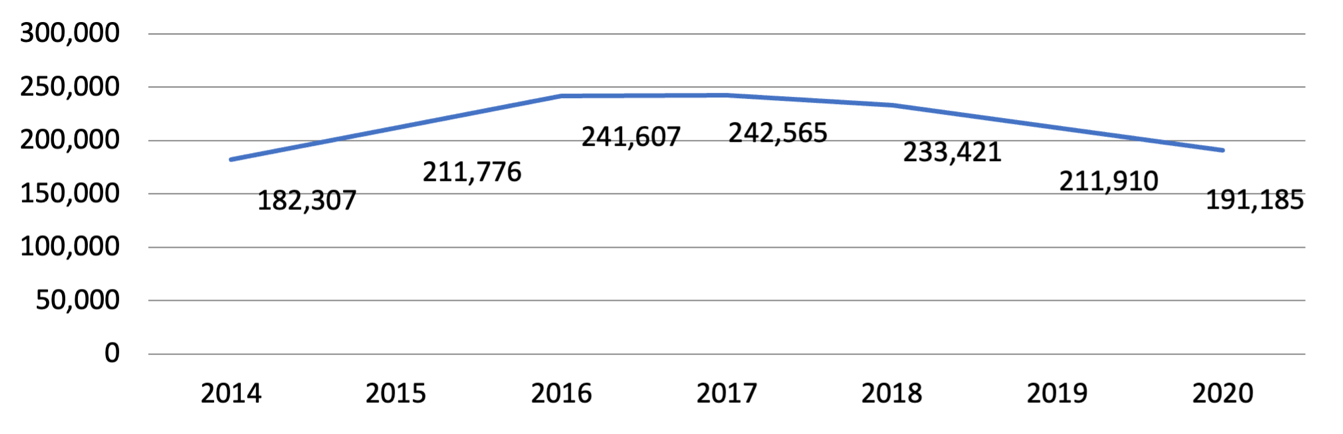

- The total workloads of Basic, Higher, and Appellate PPOs,

defined as the sum of received and cases carried over from previous

years, increased by a total of 12 percent from 2014 to 2019, as shown in

Figure 62. The workloads increased each year from 2014 to 2016

and then decreased gradually from 2017 to 2019, ending at a total of

246,182 cases.

Figure 62: Basic, Higher and Appellate PPOs Workload from 2014 to

2019

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014 – 2019 and Appellate PPOs

data

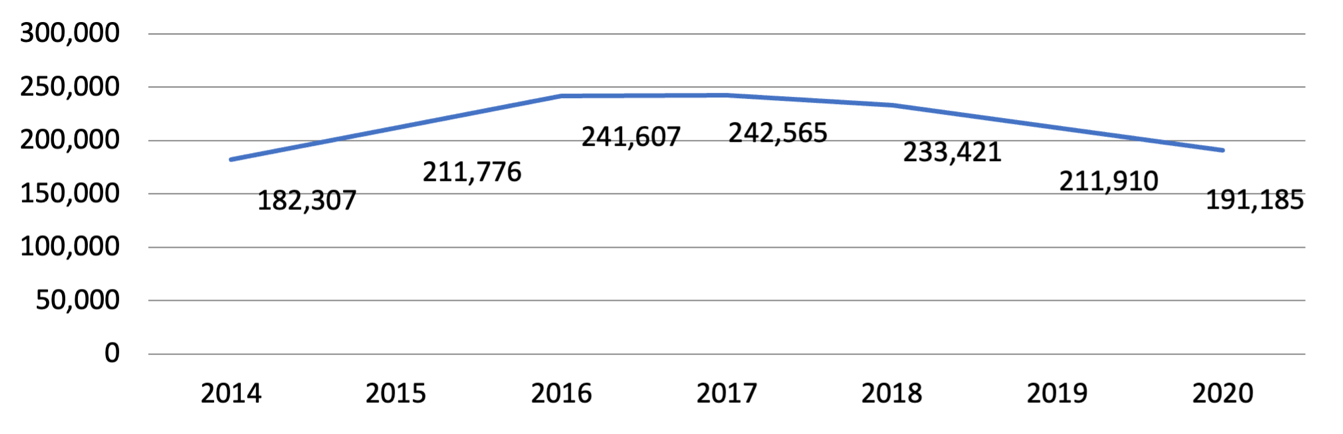

- The greatest workload increase occurred in Basic PPOs

from 2014 to 2017, a period which saw a 33 percent increase of

approximately 60,000 cases. The described increase was

connected to the new CPC and the transfer of investigation cases from

courts to PPOs. However, Basic PPO workloads decreased by four percent

in 2018 and nine percent in 2019. In 2020, Basic PPO workloads continued

to decrease, by ten percent. See Figure 63.

Figure 63: Basic PPOs Workload from 2014 to 2020

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014 – 2020

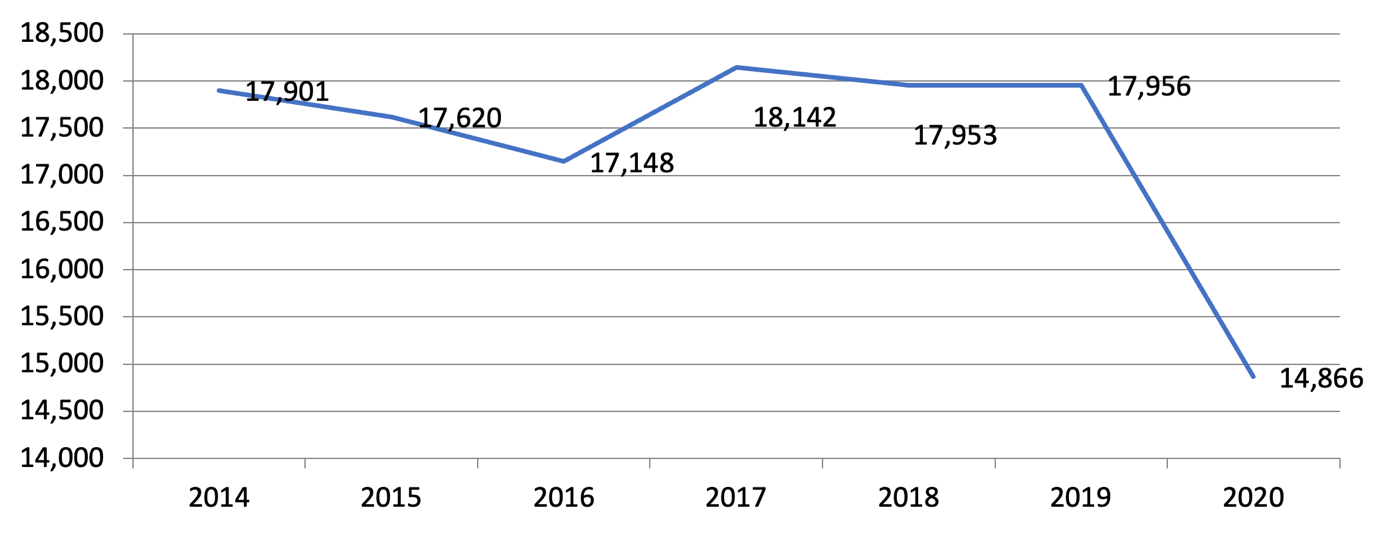

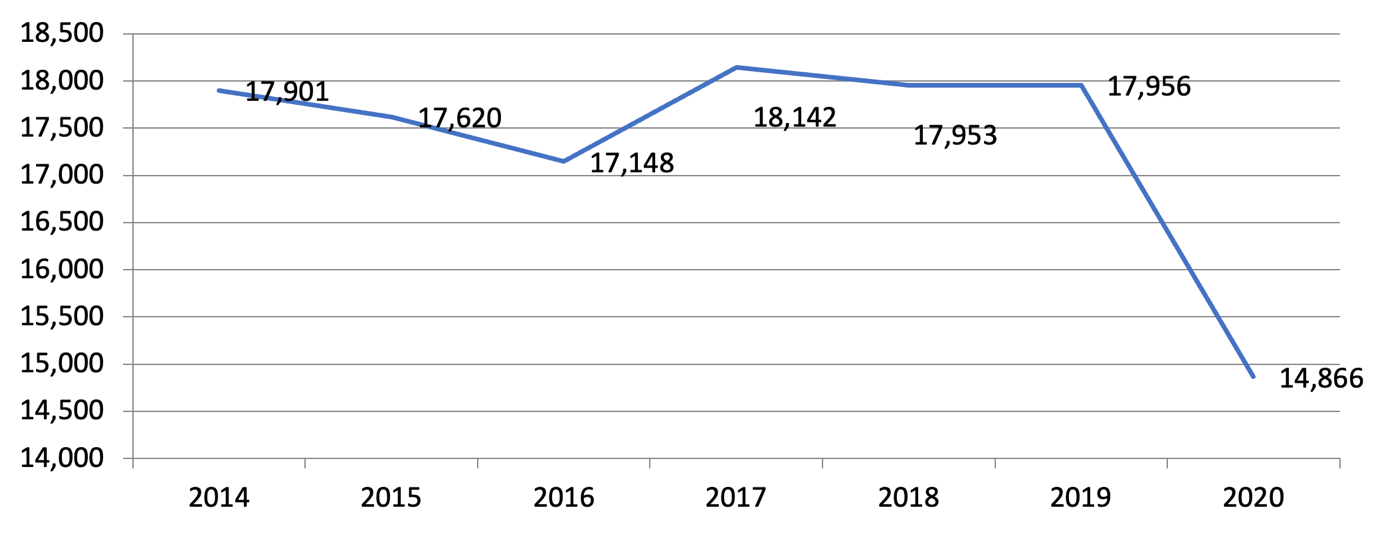

- Higher PPOs workloads were relatively stable from 2014 to

2019, ranging between 17,000 and 18,000 cases. Since the

clearance rates of Higher PPOs were between 93 and 96 percent (except

for 2018, when 100 percent was reported), the fall in the workloads in

2015 and 2016, as illustrated in Figure 64, were caused exclusively by

the lower numbers of incoming cases. With 14,866 cases in 2020, Higher

PPOs workloads decreased by 17 percent.

Figure 64: Higher PPOs Workload from 2014 to 2020

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014 – 2020

- The workloads of Appellate PPOs followed the same trends

as their caseloads, growing by three percent from 2014 to 2016 and then

dropping by 19 percent from 2016 to 2019

Efficacy and Efficiency ↩︎

Case Dispositions ↩︎

- Improved disposition rates from 2014 to 2019 were the

result of increased prosecutorial productivity overall, combined with

the continuously rising numbers of operatively active prosecutors.

Cases were disposed of by traditional dismissals, deferred prosecutions,

or indictment and trial. While the absolute number of dispositions in a

year is a measure of system productivity, a comparison of increasing and

decreasing dispositions overall by PPO, or PPO type, can contribute to

decisions about the distribution of resources and determine the impact

of reforms. The comparisons also can help identify problems or

bottlenecks within the system.

- Overall dispositions tended to track the incoming

caseloads and the workloads, i.e., increase and decrease

correspondingly. From 2014 to 2019, the number of cases

disposed of by all PPOs increased by 21 percent, including an increase

by 36 percent in Basic PPOs and decreases by 14 percent in Higher PPOs

and 17 percent in the Appellate PPOs. In Higher PPOs, the numbers of

dispositions almost always were slightly below the number of incoming

cases. In Appellate PPOs, however, the reduction was directly caused by

a fall in their workloads, and the Appellate PPOs resolved as many cases

as they received. See Figure 65. In 2020, both Basic and Higher PPOs

reported lower dispositions, by eight percent and 11 percent,

respectively.

Figure 65:Disposed Cases in Basic, Higher and Appellate PPOs from

2014 to 2019

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014 – 2019 and Appellate PPOs

Data

Clearance Rates ↩︎

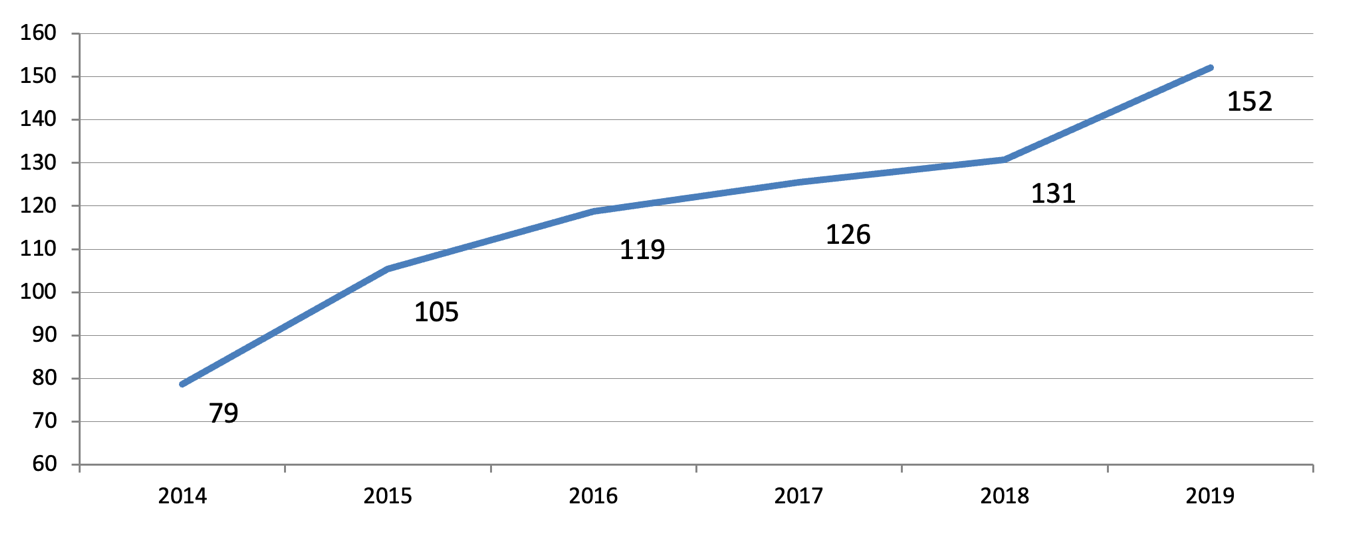

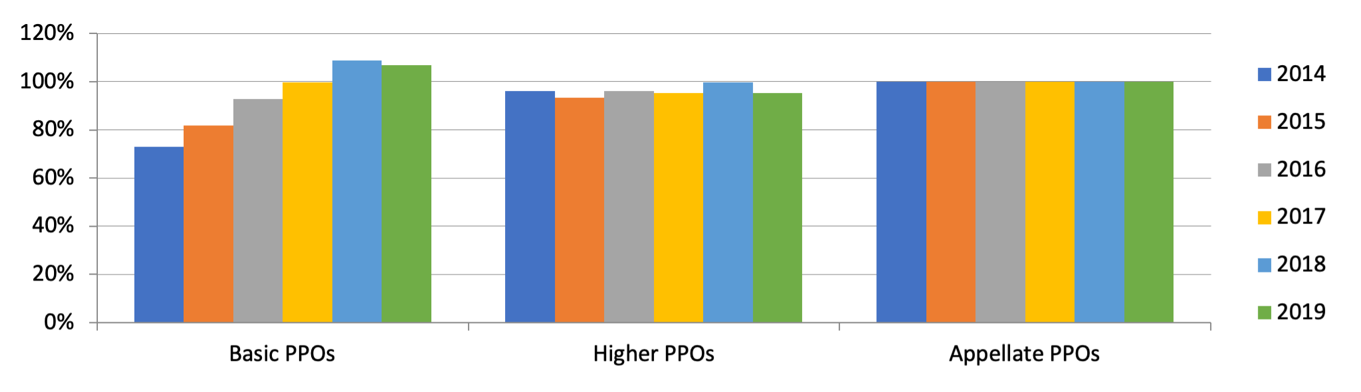

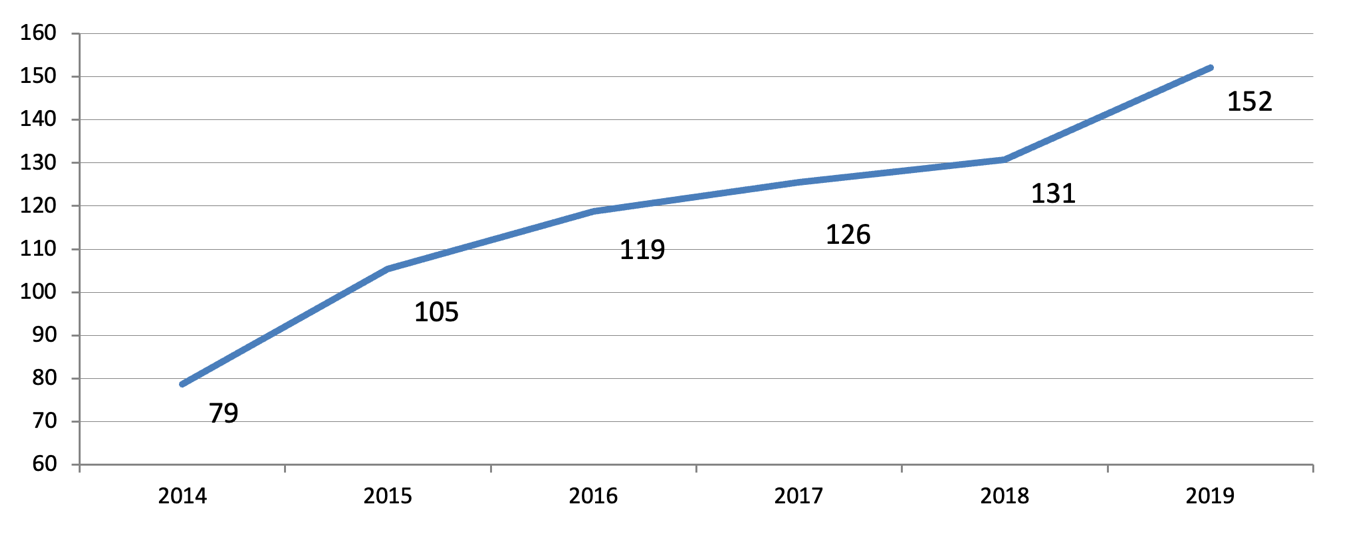

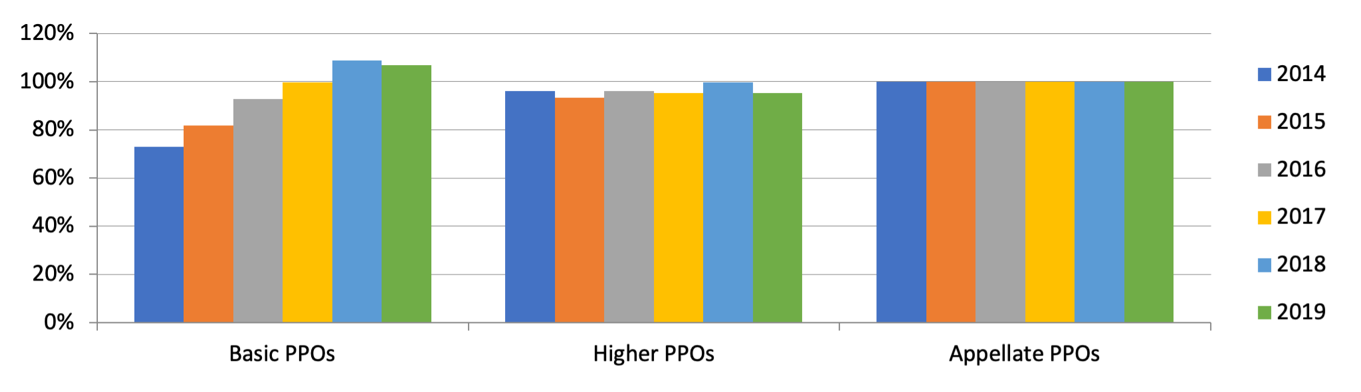

- Average total clearance rates of Serbian PPOs

consistently increased from 2014 through 2019, finally exceeding 100

percent in 2018 and 2019. Clearance rates are expressed as a

percentage, obtained by dividing the number of resolved cases with the

number of incoming cases. A clearance rate of more than 100 percent

demonstrates that the PPO resolved more cases than it received. If the

clearance rate was lower than 100 percent, the PPO disposed of fewer

cases than it received, causing the total number of cases to

increase.

- As prosecutors became more experienced in working with

the CPC that took effect in 2013, clearance rates grew consistently from

79 percent in 2014, to 86 percent in 2015, 94 percent in 2016, 99

percent in 2017, and finally to 107 percent in 2018 and 105 percent in

2019. Presumably, the increase in the number of operatively

active prosecutors in 2018 and 2019 contributed to the results for those

years, together with improved skills in the effective application of the

CPC acquired through training and consultations and the increased use of

deferred prosecution and plea bargaining.

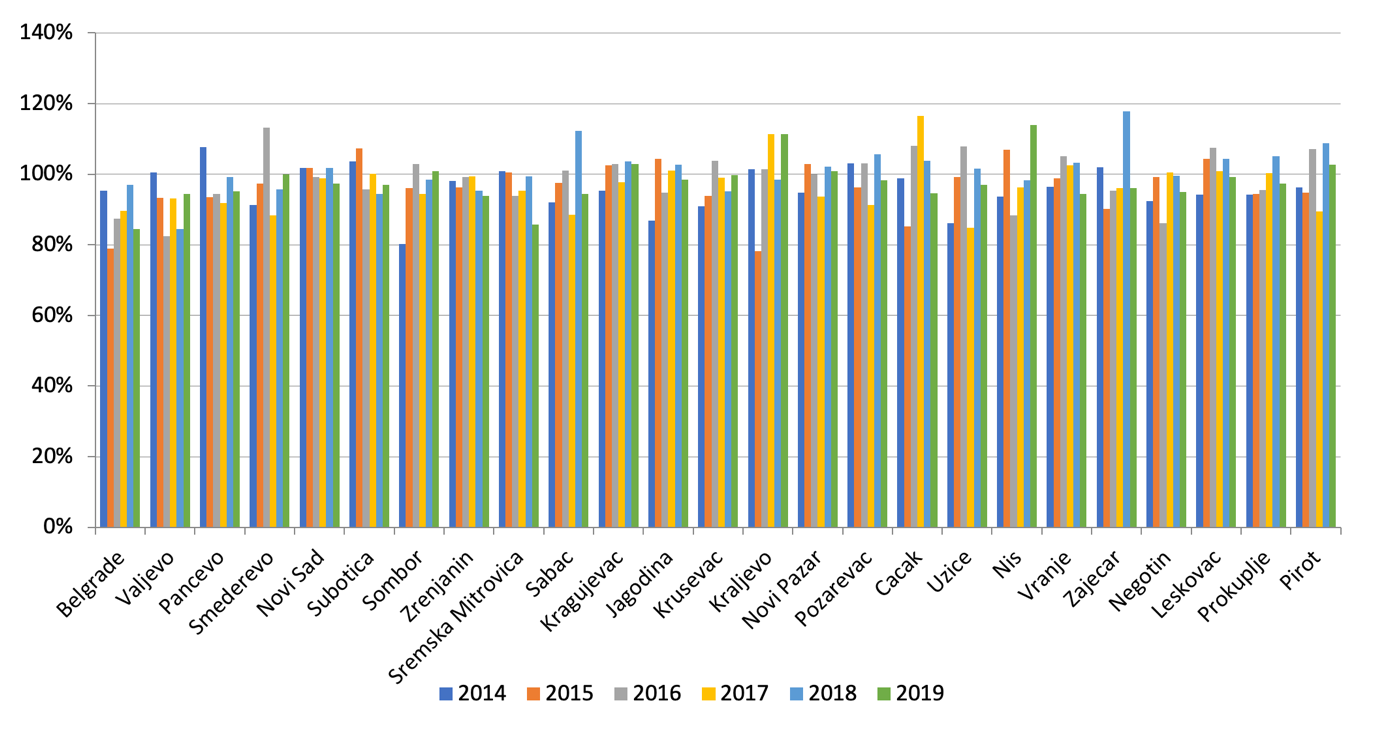

Figure 66: Clearance Rates by PPO Type from 2014 to 2019

Source: WB Calculations

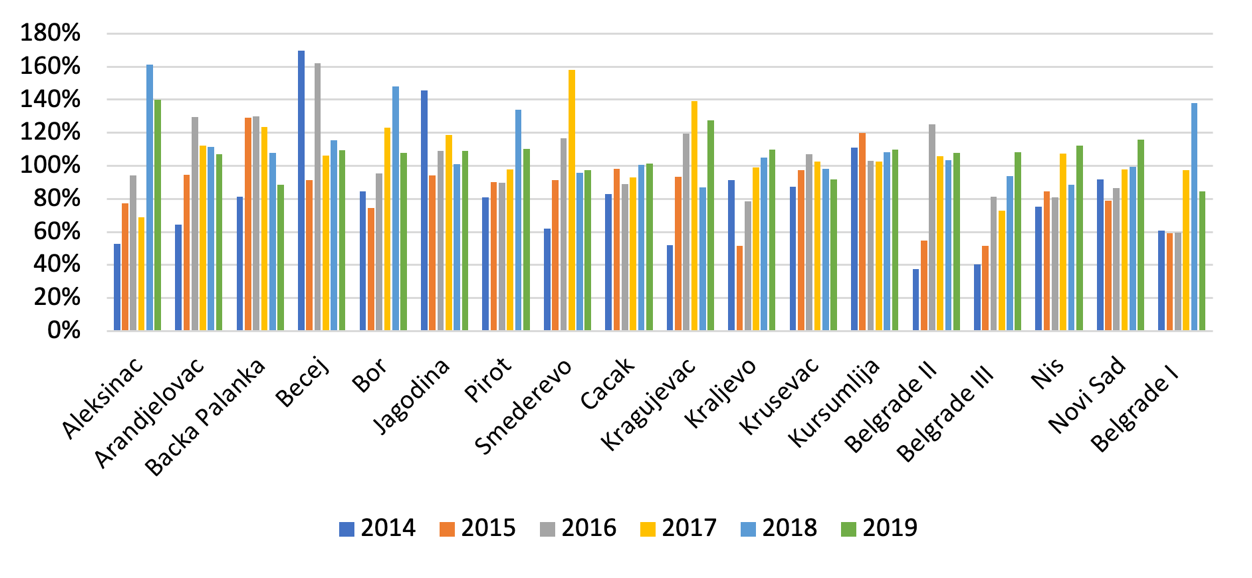

- As a group, Basic PPOs improved their average clearance

rates each year for an overall improvement of 34 percentage points from

2014 to 2019. The standout years were 2014, with a clearance

rate of 73 percent, and 2019 with a clearance rate of 107 percent. The

Basic PPO achievements in 2019, when three-quarters of the 58 Basic PPOs

achieved 100 percent or higher clearance rates in 2019, were a

significant improvement from 2014, when only one-fifth of the Basic PPOs

produced had clearance rates of at least 100 percent. See Figure 67 and

Figure 68, below. The 14 Basic PPOs making up the 24 percent were Basic

PPOs that did not reach favorable clearance rates and were mostly small

PPOs; the one exception was the First Basic PPO in Belgrade, with its

clearance rate of 84 percent in 2019. The only Basic PPOs with less

favorable clearance rates that year were the Basic PPO in Petrovac on

Mlava (68 percent) and the Basic PPO in Prijepolje (78 percent). Despite

lower dispositions in 2020, due to even lower incoming caseloads, Basic

PPOs produced a clearance rate of 112 percent.

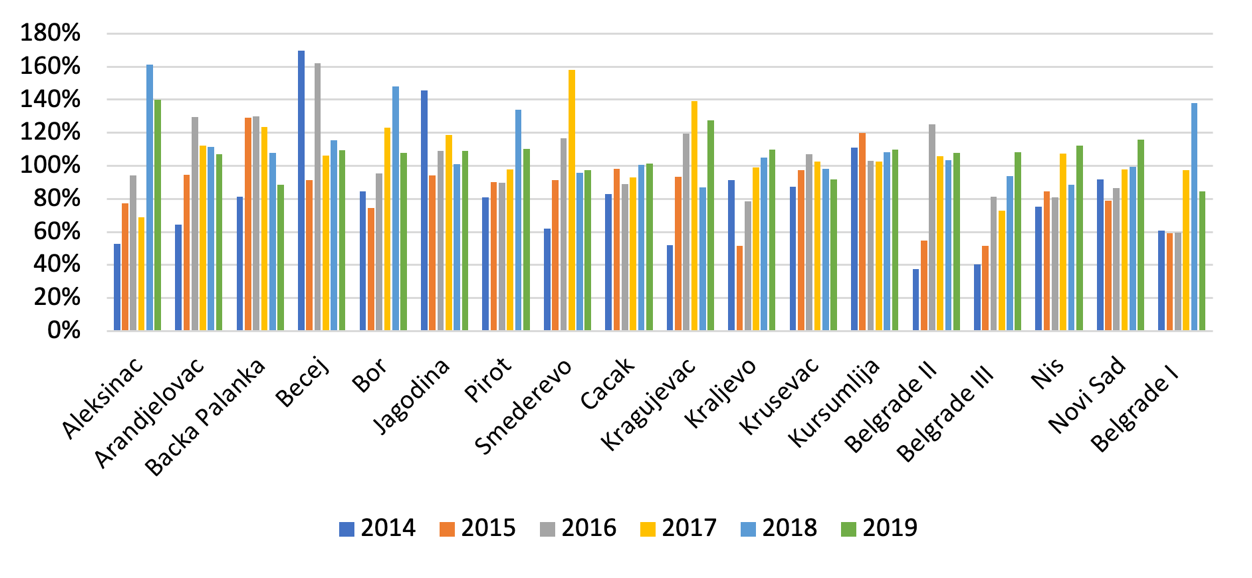

- The average clearance rates for Basic PPOs as a whole

improved despite remarkable variations among the clearance rates of

individual Basic PPOs, a phenomenon not examined in any official

analyses the FR team could locate. Only the Basic PPO in

Kursumlija achieved clearance rates of over 100 percent each year, but PPO size was no guarantee of

favorable clearance rates, as shown by the three Basic PPOs in Belgrade,

three of the four the largest PPOs in Serbia (the second largest being

Novi Sad). Belgrade’s First Basic PPO achieved a favorable clearance

rate only once from 2014 to 2019, at 138 percent in 2018. Belgrade’s Third Basic PPOs also

had only one year in which they resolved more than they received. In

contrast, clearance rates for the Second Basic PPO in Belgrade were

consistently above 100 percent from 2016 to 2019.

- Belgrade’s Basic PPO results probably were due at least

in part to their increased numbers of operatively active

prosecutors. From 2014 to 2019, the increase was 53 percent for

the First Basic PPO, 58 percent for the Second PPO, and 87 percent for

the Third.

Figure 67: Clearance Rates of Selected

Basic PPOs from 2014 to 2019

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014 – 2019 and WB

Calculations

- The overall average clearance rates for Higher PPOs

reached 100 percent only once in 2018 and otherwise ranged from 93

percent in 2015 to 96 percent in 2017. The rate for 2016 was 96

percent and the rate for 2019 was 95 percent. Although these figures

were relatively stable and relatively close to 100 percent, they show

that the pending stock consistently increased, as shown in Figure 68

below. Apart from the performance of the Higher PPO in Belgrade, there

were no other outliers among the Higher PPOs in Serbia. Another year in

which the overall average clearance rate for Higher PPOs reached the

favorable 101 percent was 2020, but as a direct consequence of the

significant drop in the Higher PPOs' incoming caseload.

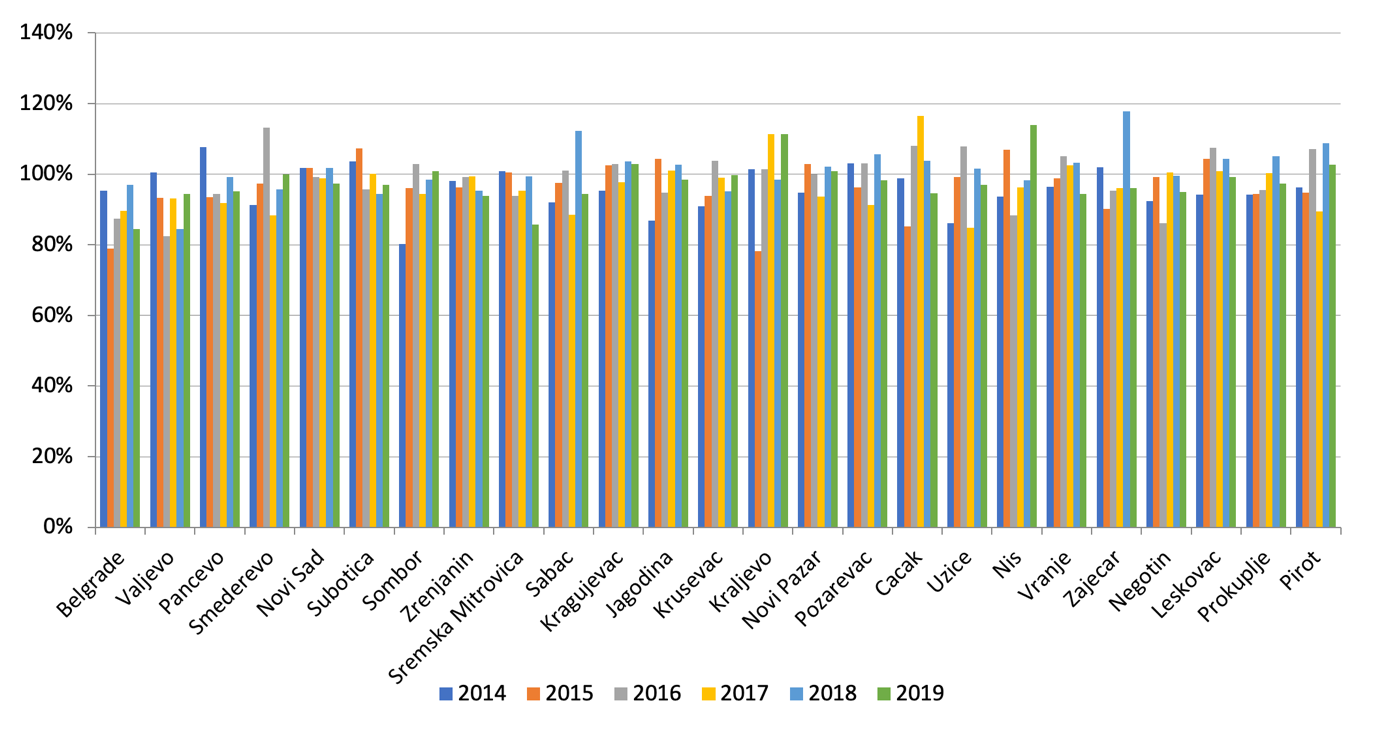

- Twenty-three of Serbia’s 25 Higher PPOs achieved

clearance rates of at least 100 percent at least once between 2014 and

2019, the outliers being the Higher PPOs in Belgrade and

Zrenjanin. The rates for the Higher PPO in Zrenjanin ranged

from 94 to 99 percent, but the variations were much more marked for the

Higher PPO in Belgrade. That office had a rate of 95 percent in 2014,

only 79 percent in 2015, 87 percent in 2016, 90 percent in 2017, 97

percent in 2018, and 84 percent in 2019.

Figure 68: Clearance Rates of Higher PPOs from 2014 to 2019 per

Higher PPO

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014 – 2019

- The four Appellate PPOs each had clearance rates of 100

percent over the six years from 2014 through 2019. As the other

data reported in this FR show, Appellate PPOs were able to perform well

with their approved levels of funding and personnel.

Timeliness in Case

Processing ↩︎

- Even clearance rates exceeding 100 percent did not

guarantee the oldest and/or most complicated cases were concluded within

reasonable timeframes. As the Prosecutorial FR noted, the

pressure to resolve cases as quickly as possible often means older and

more difficult cases continue to age, in many if not all judicial

systems, a result that undercuts public confidence in prosecutors and

the courts.

- The available statistics for Serbian PPOs still did not

provide for average times to disposition or age structure of the pending

and resolved cases. As a result, timeliness is analyzed here

using three sets of indicators: the number of carried-over cases,

congestion ratios, and disposition times as defined by the

CEPEJ.

Number of Carried-Over Cases ↩︎

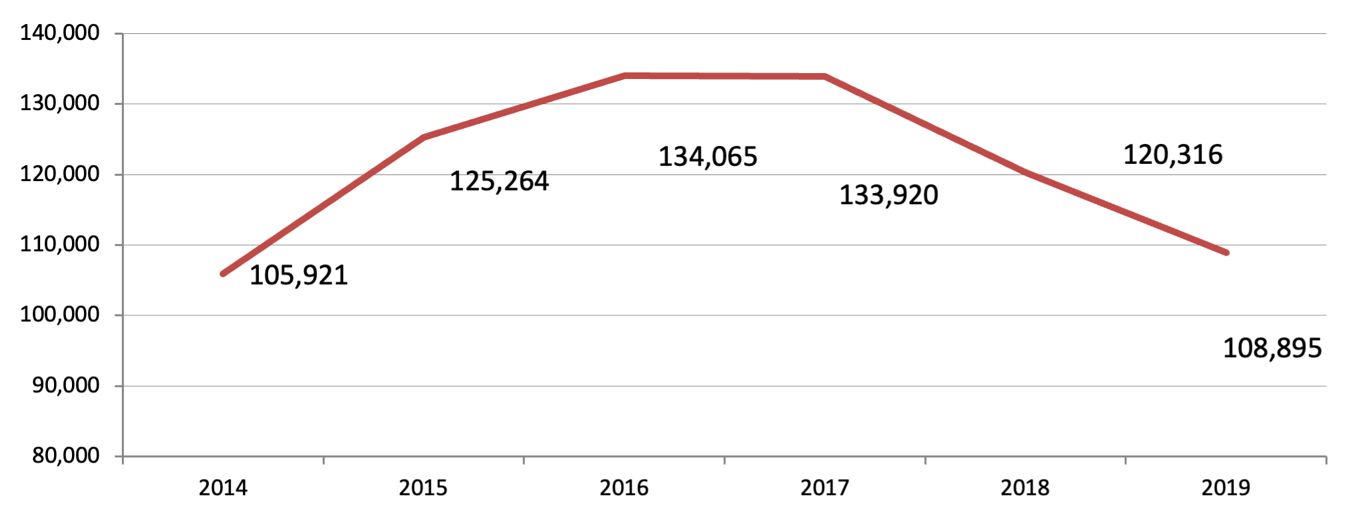

- In 2017, the total number of PPO cases carried forward

from one year to the next started decreasing after three years of

consistent increases. The increase from 2014 to 2017 was 27

percent, while in the following years, the pending stock declined by a

total of 19 percent and more than 25,000 cases, as shown by. Figure 69.

As expected given their share of the total number of cases in the

system, the carried-over cases in Basic PPOs influenced the totals the

most.

Figure 69: Carried-Over Cases in PPOs from 2014 to 2019

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014 – 2019

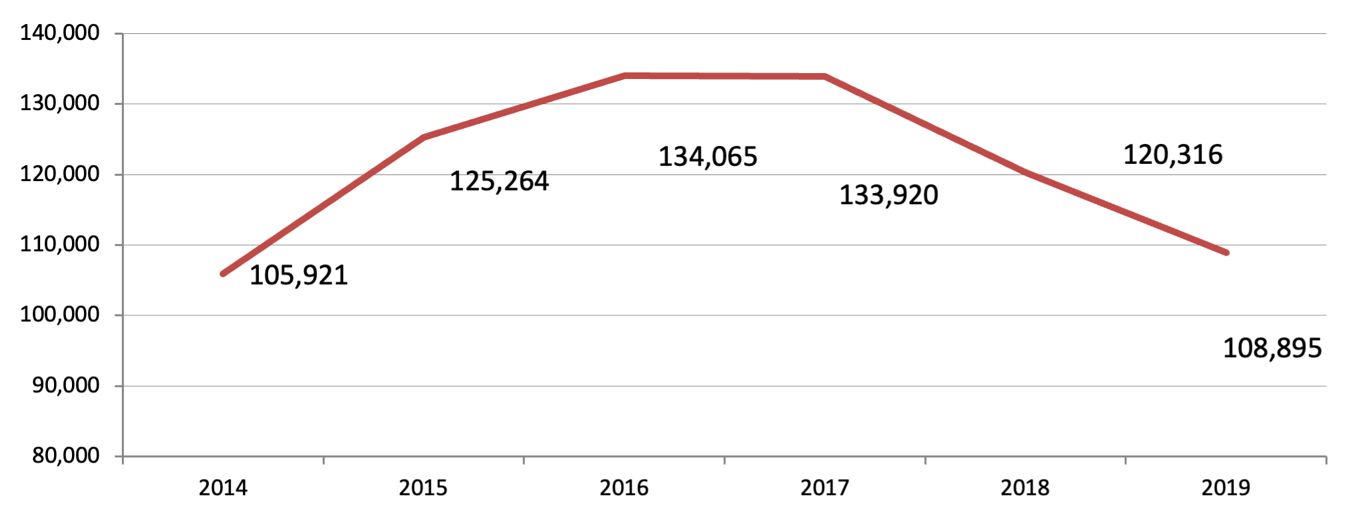

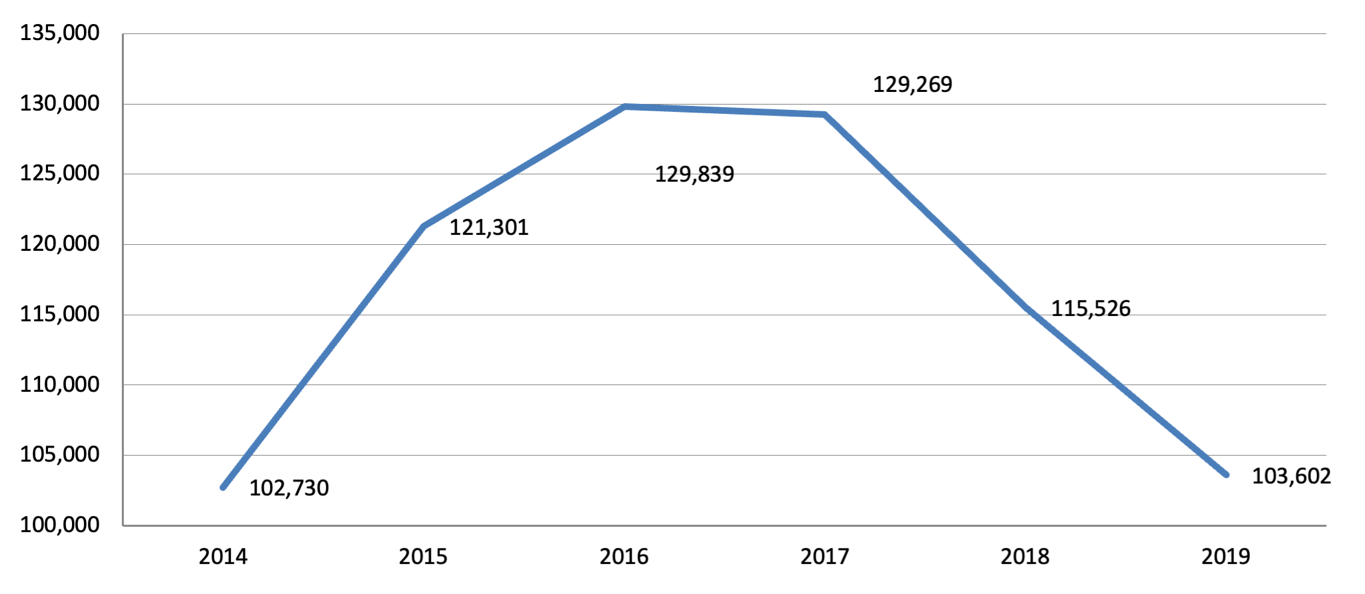

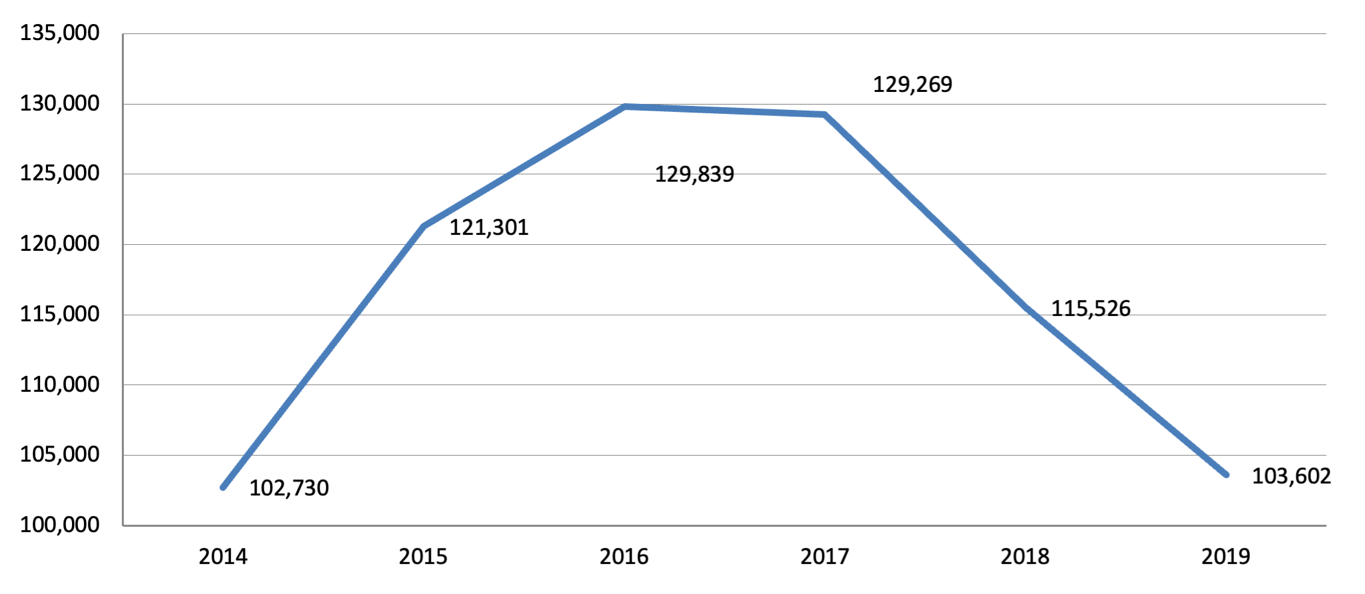

- The number of carried-over cases in Basic PPOs grew until

2016-2017, but the numbers for Higher PPOs grew persistently every year

between 2014 and 2019 for a total increase of 66 percent. The

pending stock of Basic PPOs declined by 11 percent in 2018 and 10

percent in 2019. The contrast between Basic and Higher PPOs is shown by

Figure 70 and Figure 71.

Figure 70: Carried-Over Cases in Basic PPOs from 2014 to 2019

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014 – 2019

Figure 71:Carried-Over Cases in Higher PPOs from 2014 to 2019

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014 – 2019

- These totals would be very different if ‘unknown

perpetrators cases,’ also known as KTN cases, were included. At the beginning of 2019, there

were 472,802 KTN cases pending in Serbian PPOs, of which 92 percent were

in Basic PPOs. The clearance rates for KTN cases in Basic PPOs was 64

percent in 2014, 48 percent in 2015, 79 percent in 2016, 128 percent in

2017, 93 percent in 2018, and 146 percent in 2019. Higher PPOs achieved

a clearance rate of 32 percent for KTN cases in 2014, 119 percent in

2015, 159 percent in 2016, 687 percent in 2017, 151 percent in 2018, and

100 percent in 2019.

- As noted in the discussion of clearance rates, from 2014

through 2019, Appellate PPOs had very few carried-over cases.

The Appellate PPOs in Kragujevac and Novi Sad resolved all of their

cases each year from 2014 to 2019, while the Appellate PPO in Nis

carried over six to 17 cases each year. The Appellate PPO in Belgrade

carried over 50 cases in 2018 and three cases in 2019. For both Nis and

Belgrade PPOs, the number of cases carried forward was negligible,

representing at most one percent of their workloads.

Congestion Ratios ↩︎

- Congestion ratios are calculated by dividing the total

number of unresolved cases at the end of one year by the number of

resolved cases during that same year. This ratio should

indicate what effect the number of carried-over cases had on PPO

performance. While there is no standard goal for prosecutorial

congestion ratios, larger numbers indicate higher congestion levels and

probable delays. A congestion ratio should be under 1.00 and ideally

under 0.50, to ensure there are far fewer unresolved cases at the end of

the year than the number of cases resolved during the year.

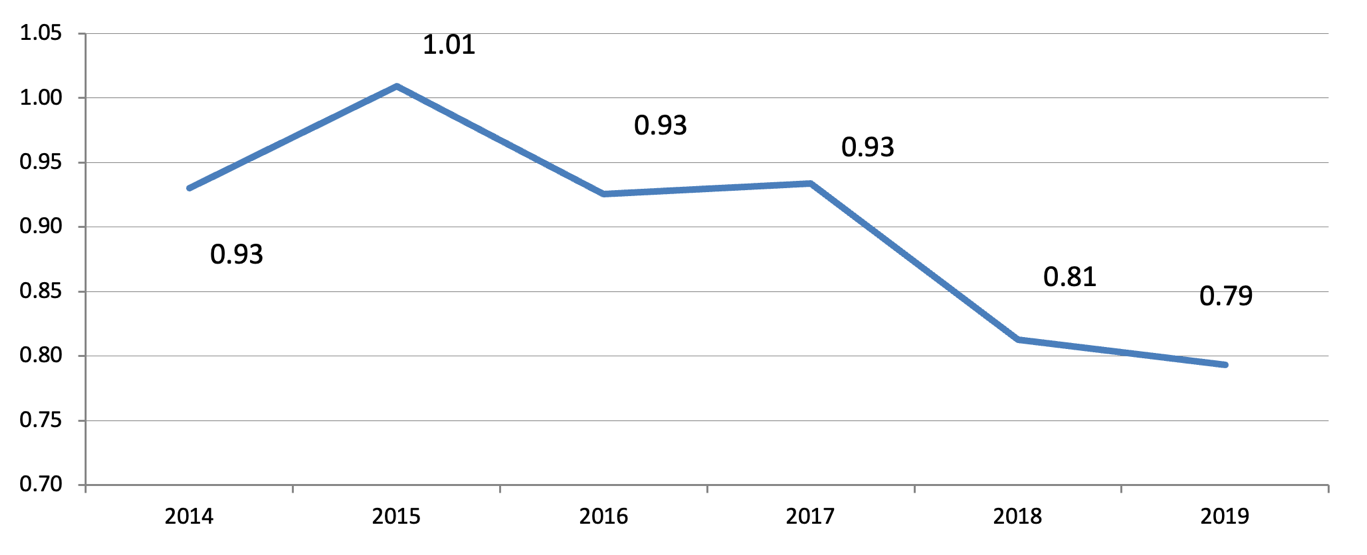

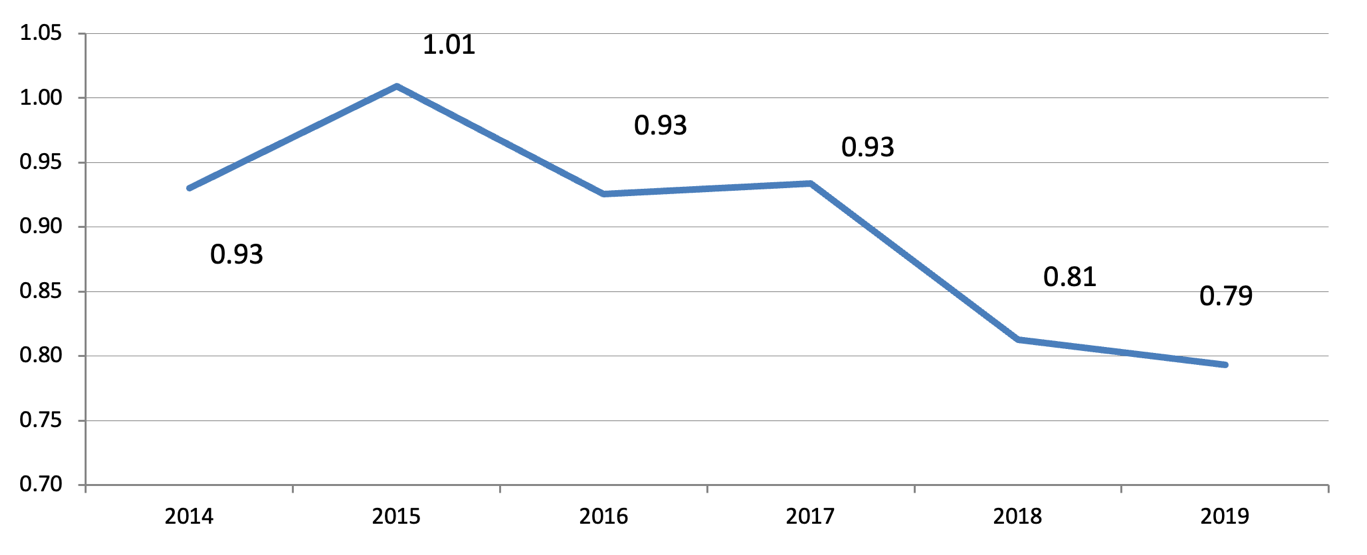

- Serbia’s overall prosecutorial congestion ratios from

2014 to 2019 ranged from 0.79 to 1.01, as shown in Figure 72 below, with

the most recent ratios leaving room for progress. The

congestion ratio in 2018 was 0.81, with 120,316 unresolved and 148,087

resolved cases at the end of the year. For 2019, the ratio was 0.79

based on 108,895 unresolved cases and 137,287 resolved cases.

Figure 72: Overall Congestion Ratios of Basic, Higher and Appellate

PPOs from 2014 to 2019

Source: WB Calculations

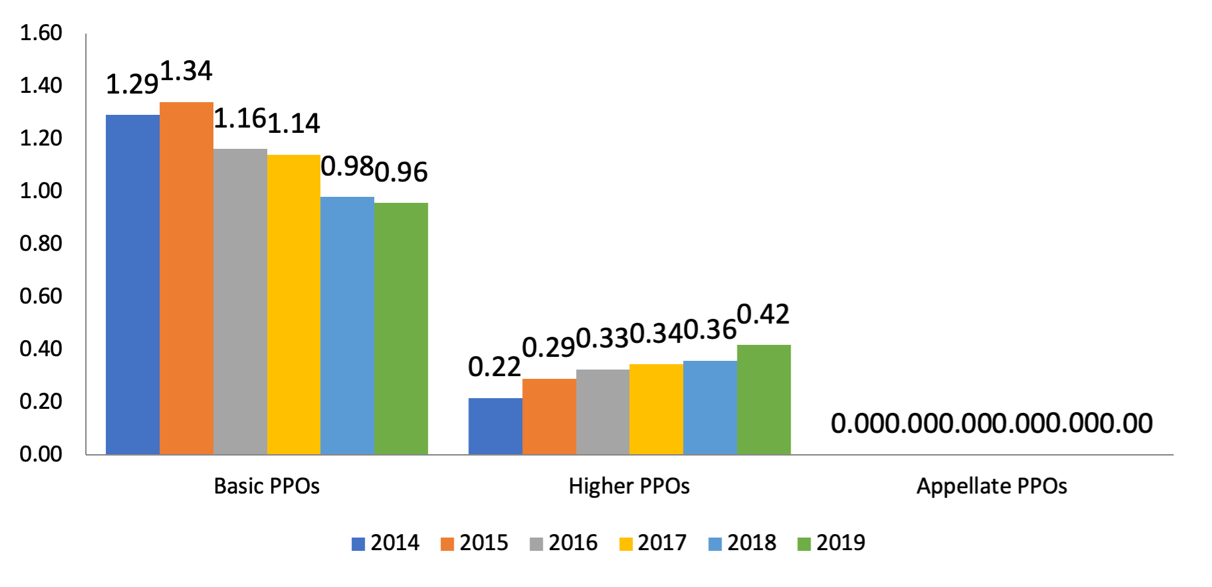

- Although they were improving, Basic PPOs continued to

have the highest congestion ratios among the three PPO categories, with

results two to six times higher than those of Higher PPOs.

There was no congestion in Appellate PPOs, as shown by Figure

73.

Figure 73: Congestion Ratios per PPO Type from 2014 to 2019

Source: WB  Calculations

Calculations

- Congestion ratios for individual Basic PPOs in 2019

continued to vary widely as shown in Figure 74 below, with nine of them

exceeding 1.00. The highest congestion ratios were recorded in

the Second and the Third Basic PPOs in Belgrade, at 2.38 and 2.13,

respectively. The PPO of Petrovac on Mlava followed with 1.64. In

addition to the Second and Third Basic PPOs in Belgrade and the office

in Petrovac on Mlava, the Basic PPOs with ratios exceeding 1.00 included

the Basic PPOs in Ub (1.60), Belgrade’s First (1.51), Novi Sad (1.19),

Lazarevac (1.16), Obrenovac (1.06), and Pozarevac (1.02). Nevertheless,

22 of the 58 Basic PPOs, or 38 percent, reported ratios equal to or

lower than 0.50 in 2019, showing that more efficient performance is

possible, at least in small and medium PPOs. For example, the Basic PPO

in Kragujevac had a congestion ratio of 0.25, the Basic PPO in Leskovac

0.36, and the Basic PPO in Senta 0.09.

Figure 74: Congestion Ratios of Selected

Basic PPOs in 2019

Source: WB Calculations

- The overall congestion ratios in Higher PPOs remained

under 0.50 every year from 2014 to 2019, although they increased

slightly each year. The overall ratios stayed within the

desired range of less than 0.50, although they almost doubled from 2014

to 2019 due to extraordinarily high congestion in Belgrade’s Higher PPO.

The ratio for Belgrade congestion deteriorated greatly after 2014, when

it was 0.34 even though the number of prosecutors for that office

increased from 43 in 2014 to 64 by 2019; the ratio was 0.73 in 2015,

1.00 in 2016, 0.96 in 2017, 1.12 in 2018, and 1.43 in 2019. In 2019, the

highest congestion ratio after Belgrade was reported in Sremska

Mitrovica, at 0.46. The greatest contrast to Belgrade and Sremska

Mitrovica was found in Leskovac, where the congestion decreased from

0.20 in 2014 to 0.02 in 2018 and 2019

Time to Disposition ↩︎

- Since Serbian PPOs still were not tracking the duration

of individual cases after the analyses done for the Prosecutorial FR,

this review continues to use the CEPEJ methodology for the calculation

of the theoretical time necessary for a pending case to be disposed of,

taking into consideration the then-current pace of work of

PPOs. The indicator is reached by dividing the number of

pending cases at the end of a particular period by the number of

resolved cases within that period, multiplied by 365 days. The resulting indicator is not an

estimate of the average time needed to process a case but a theoretical

average of the duration of a case within a specific system (e.g., by

individual PPO, types of PPOs, PPOs by region, or PPOs by

country).

- Disposition times of Serbian prosecutors decreased

gradually from 2014 to 2019, although they continued to be two to six

times higher in Basic than in Higher PPOs. Disposition times of

Higher PPOs are expectedly lower than in Basic PPOs as their cases are

mostly urgent since the defendants are in custody and their jurisdiction

is narrower. The overall disposition time for the system decreased from

339 days in 2014 to 290 days in 2019. The decrease in Basic PPOs was

from 471 to 349 days. The Third Basic PPO in Belgrade struggled the most

in terms of disposition time and was the only Basic PPO that exceeded

one thousand days for five years in a row from 2014 to 2018. Its

disposition almost halved from 2014 (1,374 days) to 2019 (777 days). The

Basic PPOs with the best disposition times in 2019 were those in Senta

(34 days), Raska (36 days), and Veliko Gradiste (42 days). Moreover,

Veliko Gradiste’s calculated disposition time of 20 days in 2018 was a

91 percent improvement over 2014. See Figure 75.

Figure 75: Disposition Times of Selected

Basic PPOs from 2014 to 2019

Source: WB Calculation

- The Higher PPO in Belgrade was responsible for the

consistently increasing average disposition times for Higher PPOs

overall, times that almost doubled from 2014 (79 days) to 2019 (152

days). There was no official analysis available to the FR team

to explain the cause of the increase for Belgrade. While most other PPOs

managed to keep their disposition times under 100 days,

for Belgrade, the disposition time of 124 days in 2014 quadrupled to 523

days in 2019. The Higher PPO in Belgrade had a 25 percent drop in the

number of resolved cases from 2014 to 2019, its clearance rate decreased

from 95 to 84 percent, and its carried-over stock increased from 1,174

cases in 2014 to 3,685 in 2019. See Figure 76 below.

Figure 76: Disposition Times of Higher PPOs from 2014 to 2019

Source: WB Calculation

- As with other efficiency indicators, disposition times of

Appellate PPOs were excellent from 2014 to 2019, since these PPOs

essentially resolved all of their incoming cases each

year.

Efficiency per Prosecutor ↩︎

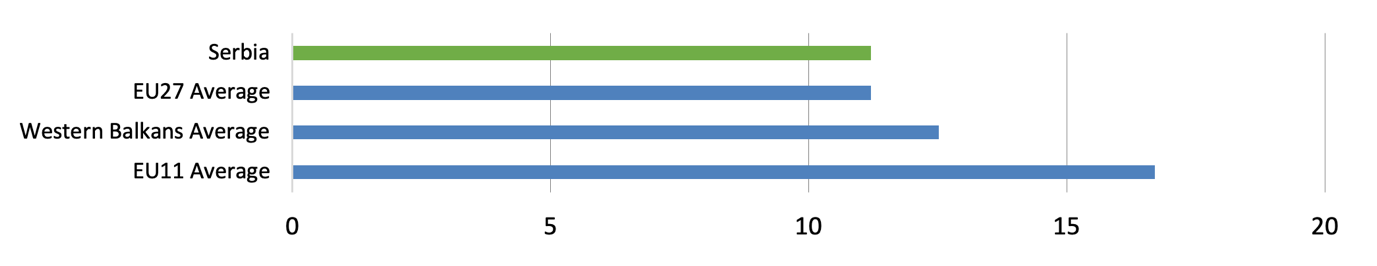

- According to the CEPEJ 2020 report (2018 data), the

number of Public Prosecutors per 100 thousand inhabitants in Serbia was

11.2, which was an increase of 2.4 prosecutors over the previous CEPEJ

report that examined 2016 data, and in line with the EU27

average. The EU11 average for 2018 was 16.7, and the Western

Balkans average was 12.52. When compared to individual regional peers

from the EU11 and Western Balkans, only Bosnia and Herzegovina had a

similar ratio of 10.7. See Figure 77 below.

Figure 77: Number of Public Prosecutors per 100,000 Inhabitants –

CEPEJ 2020 Report

Source: CEPEJ Report 2020 (2018 data)

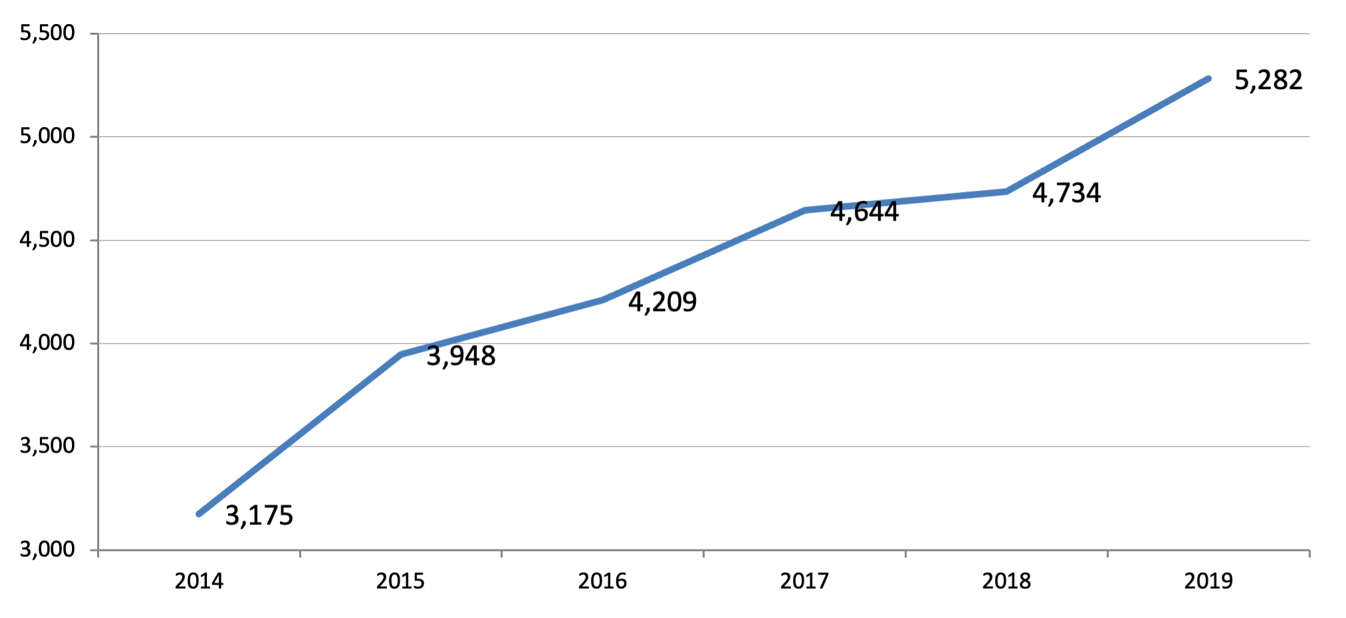

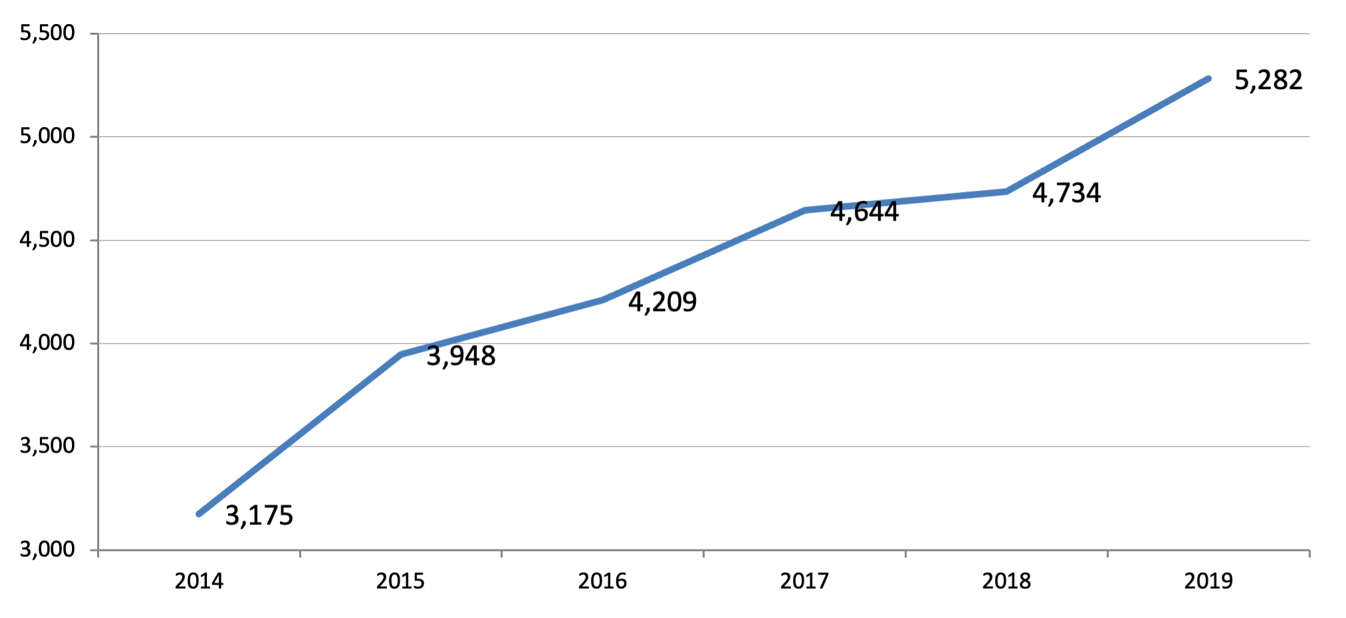

Caseloads per Prosecutor

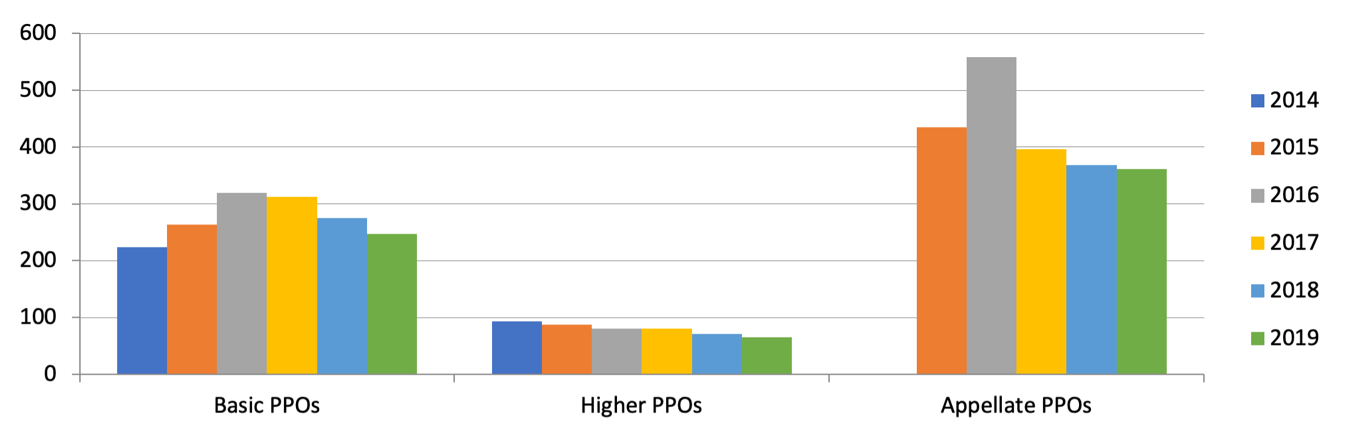

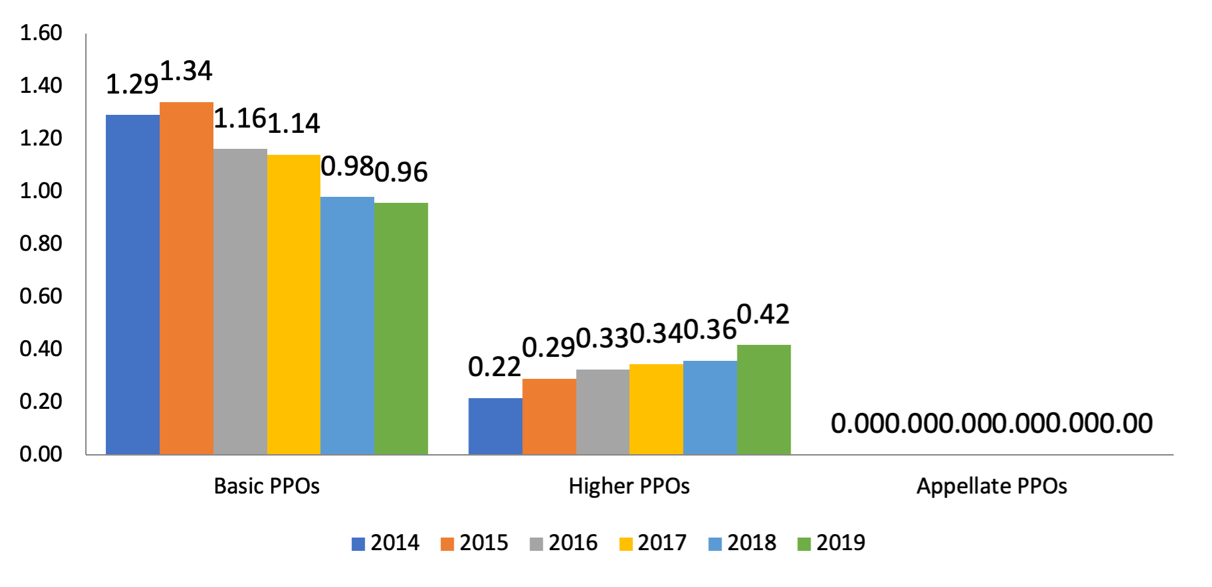

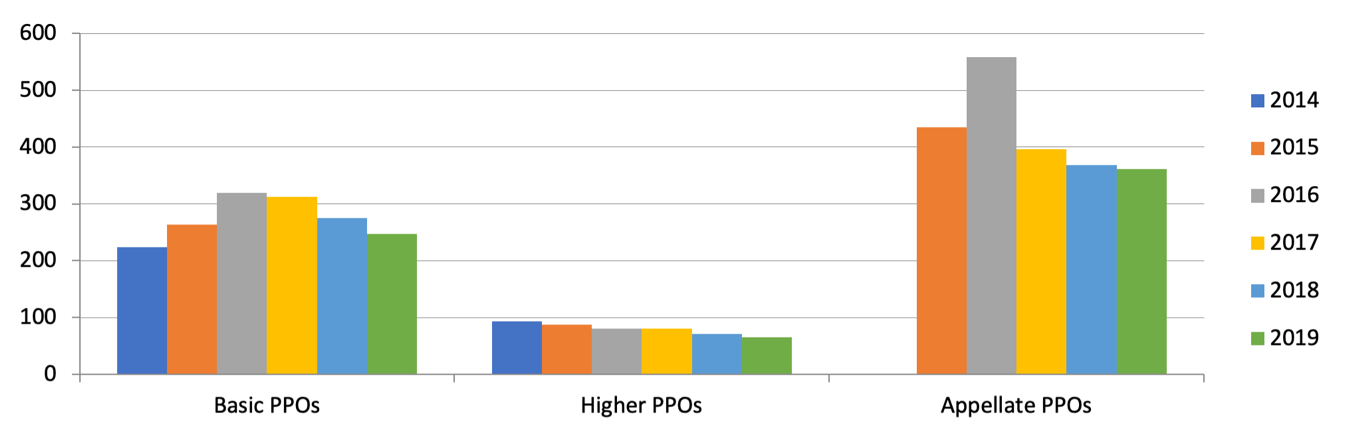

- The caseloads – meaning incoming cases -- for prosecutors

within all PPO types decreased from 2014 to 2019. Caseloads per

prosecutor decreased by 25 percent in Basic PPOs, by 33 percent in

Higher PPOs, and by 18 percent in Appellate PPOs, as presented in Figure

78 below.

Figure 78: Caseload per Prosecutor in Basic, Higher and Appellate PPOs from 2014 to 2019

Source: WB Calculations

- After three years of increases, the number of incoming

cases in Basic PPOs started dropping in 2017, as the number of

prosecutors working on cases increased by almost one quarter from 2014

to 2019. In Higher PPOs, the number of incoming cases varied

between 13,000 and 15,000 thousand, while the number of prosecutors grew

by 30 percent, causing the caseload per prosecutor to drop. However, the

increase in the number of Higher PPOs prosecutors primarily was

connected to the establishment of the four specialized anti-corruption

departments. These prosecutors could not be excluded from the total for

this calculation since it could not be determined how many of the

prosecutors in the four PPOs were working in the anti-corruption

departments versus other departments. See Table 13 below.

Table 13: Caseload and Prosecutors in Basic and Higher PPOs from 2014

to 2019

| Basic PPOs |

Caseload |

108,922 |

110,532 |

120,424 |

113,620 |

108,479 |

101,312 |

| Prosecutors |

355 |

344 |

350 |

350 |

429 |

439 |

| Higher PPOs |

Caseload |

15,319 |

14,639 |

13,451 |

14,162 |

13,263 |

13,316 |

| Prosecutors |

158 |

157 |

161 |

167 |

186 |

206 |

Source: RPPO Annual Reports 2014 – 2019

- By 2019, each prosecutor in Basic PPOs had an average of

231 incoming cases, but the substantial caseload differences among

prosecutors in Basic PPOs described in the Prosecutorial FR

persisted. Prosecutors in Higher PPOs generally had lower

numbers of incoming cases in 2019, ranging from a low of 23 cases in

Kraljevo to a high of 194 cases in Zrenjanin. Of the 25 Higher PPOs, in

17 (68 percent) prosecutors had caseloads below the national

average.

- Caseload per prosecutor decreased in Appellate PPOs to

248 cases in 2019. While Appellate PPOs in Belgrade and

Kragujevac reported a drop in incoming cases over the past two years,

the number of these cases were up in Nis and Novi Sad.

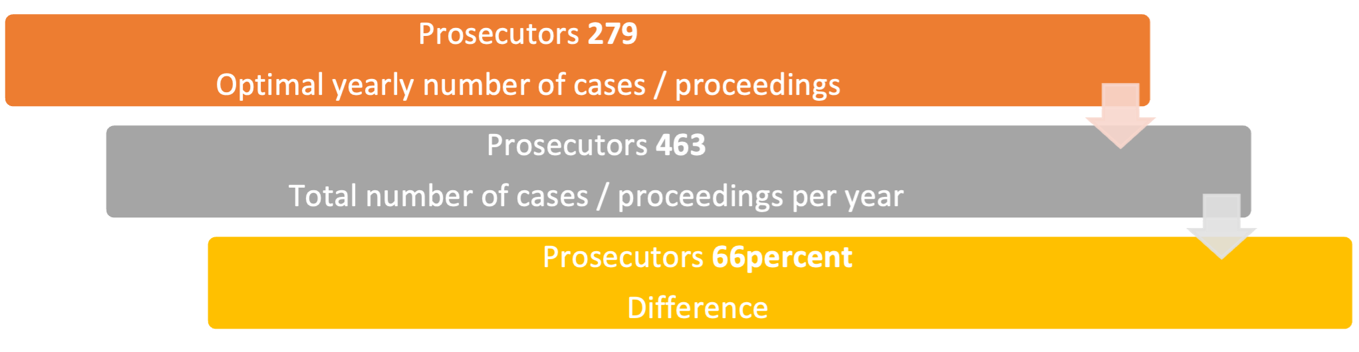

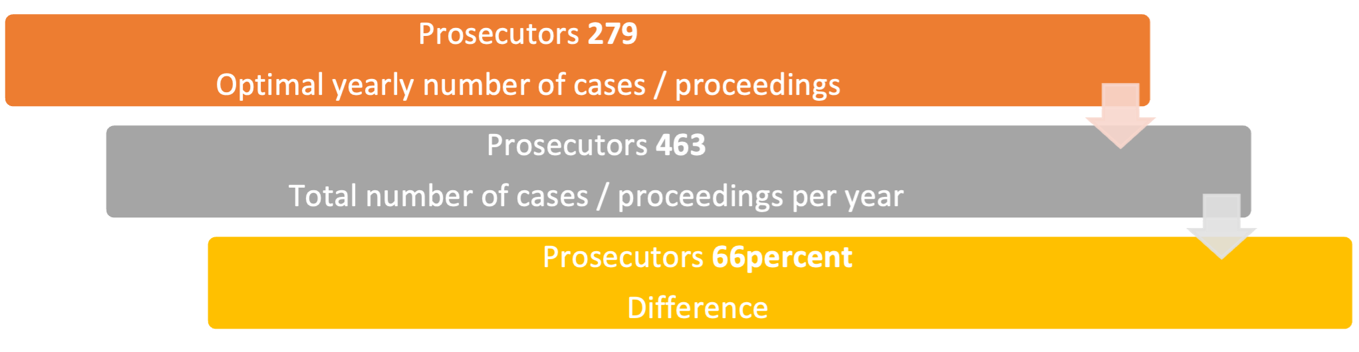

- Although the number of prosecutors has increased over the

last few years, the prosecutors evaluated that their annual caseload

considerably exceeds the optimal one. The difference between

the actual caseload and the caseload that prosecutors perceive as

optimal is significant. According to prosecutors, the actual caseload

exceeded the optimal one by 66percent on average. The perceived range of

actual and optimal caseload varies among different types of courts and

prosecutor offices. Prosecutors from basic prosecutor offices cite a

higher number of cases they usually work on.

Dispositions per Prosecutor

- Across all PPO types, average dispositions per prosecutor

were very similar to the trends for caseloads per prosecutor.

From 2014 to 2019, there was an increase of 10 percent for average

dispositions per prosecutor in Basic PPOs, and decreases in Higher and

Appellate PPOs by 29 and 17 percent, respectively. See Figure 79

below.

Figure 79: Dispositions per Prosecutor in Basic, Higher and

Appellate PPOs from 2014 to 2019

Source: WB Calculations

- Dispositions per prosecutor in Basic PPOs grew each year

from 2014 to 2016 and then declined from 2017 to 2019, with stable or

increasing dispositions per prosecutor for most, but not all, Basic PPOs

from 2014 to 2019. Some PPOs, like the three Basic PPOs in

Belgrade, increased their numbers of prosecutors while others lost

prosecutors (e.g., the Basic PPOs in Leskovac, Pancevo, and Sabac). On

the other hand, the Basic PPO in Novi Sad added four prosecutors in 2019

compared to 2014, its caseload of incoming cases decreased by six

percent, and the number of disposed of cases per prosecutor fell by 18

percent.

- Average dispositions per prosecutor in Basic PPOs varied

more than the caseloads per prosecutor by a factor of four.

They ranged from 131 in Prijepolje to 562 in Kursumlija. More than

one-half or 31 of the Basic PPOs achieved lower-than-average

dispositions per prosecutor. In eight Basic PPOs, dispositions per

prosecutor were average, and in one-third or 19 Basic PPOs, the

depositions per prosecutor were above average.

- However, as was true for caseloads, disposition numbers

per prosecutor in Basic PPOs still did not correlate to PPO

size. Small PPOs reached some of the highest disposition rates

per prosecutor, and PPOs with consistently above-average disposition

rates were all small in size, with six or fewer prosecutors.

- The decreasing disposition rates per prosecutor in Higher

PPOs indicated that at least some of the Higher PPOs were receiving the

additional staff they needed. Disposition rates for Higher PPOs

overall were half those of Basic PPOs and Appellate PPOs, and reduced

consistently over time. However, based on interviews conducted by the FR

team, the decreased disposition times probably were due to the increased

number of Higher PPO prosecutors assigned to specialized

departments.

- Appellate PPO prosecutors managed to dispose of the same

number of cases they received.

Efficiency

of Specialized PPOs and Specialized PPOs Departments in Higher PPOs ↩︎

- With the notable exception of the PPO for Organized

Crime, Specialized PPOs and PPOs’ specialized departments in Serbia were

burdened by performance issues, unstable and low clearance rates, high

congestion rates, and high disposition times.

- Based on all the efficiency indicators discussed in this

Chapter, procedures used by the PPO for Organized Crime to achieve its

results from 2014 to 2019 should be adopted by other PPOs as often as

possible. The organized crime PPO’s relatively low caseload of

474 cases in 2019 was almost double its caseload for 2014 when 238 cases

were received, but the office still moved its cases through the system

well. The clearance rate reached 102 percent in 2014 and stood at 99

percent in 2015, 92 percent in 2016, 97 percent in 2017, 95 percent in

2018, and 98 percent in 2019. Disposition times varied from 50 days in

2017 to 111 days in 2016; in 2019, the time was 89 days. The congestion

rates were in the ideal category, below 0.50 from 2014 to 2019.

- Conversely, results for the PPO for War Crimes varied

significantly from a clearance rate of 380 percent in 2015 to 25 percent

in 2017. In 2018 and 2019, its clearance rate stabilized at 107

and 100 percent, respectively. Congestion rates followed the erratic

variations, but the congestion was regularly well over 1.00; in 2019, it

was 1.58. Only in 2015 did this value drop to a satisfactory 0.37.

Similarly, disposition times were high, 967 in 2014, 134 in 2015, 557 in

2016, 1,590 in 2017, 706 in 2018, and 576 in 2019. However, all these

variations relate to very small workloads; 20 cases were received in

2014, 10 in 2015, 34 in 2016, 56 in 2017, 29 in 2018, and 28 in

2019

- The Special Prosecution Office for High Tech Crime within

the Belgrade Higher PPO more than quadrupled its pending stock/workload

from 226 cases in 2015 to 952 cases in 2019, primarily due to low

clearance rates. Its clearance rate

was 68 percent in 2015, 42 percent in 2016, 67 percent in 2017, 58

percent in 2018, and 67 percent in 2019. Low clearance rates (68 percent

in 2015, 42 percent in 2016, 67 percent in 2017, 58 percent in 2018, and

67 percent in 2019) were accompanied by high congestion ratios and high

disposition times. The congestion ratio jumped from 1.47 in 2015 to 4.96

in 2019, while the disposition times ranged from a low of 536 days in

2015 to a high of 1810 days in 2019. Although this could not be verified

from the available data, the high congestion rates, high disposition

times and low clearance rates well may have been due to the complex

nature of many of the cases. The caseload for 2014 was illegible in that

Annual Report; in 2015, the caseload was 226, 322 in 2016, 252 in 2017,

324 in 2018, and 287 in 2019.

- The specialized departments to combat corruption,

established in 2018 in four Higher PPOs received 9,682 criminal

complaints in their first year of operation, most of which had been

started by Higher PPOs before 2018. The transfer of these cases

from other Higher PPOs probably enhanced the workloads and disposition

numbers of the original PPO. In total, 3,696 criminal complaints were

resolved in 2018, of which 75 percent were dismissed. Also, during 2018,

465 days were needed to resolve a criminal complaint, while the

clearance rate was only 44 percent. In 2019, the departments disposed of

5,146 more cases and raised their overall clearance rate to 78 percent.

However, due to the increased workload, the average disposition time

increased to 545 days.

Efficiency Perceived by

Stakeholders ↩︎

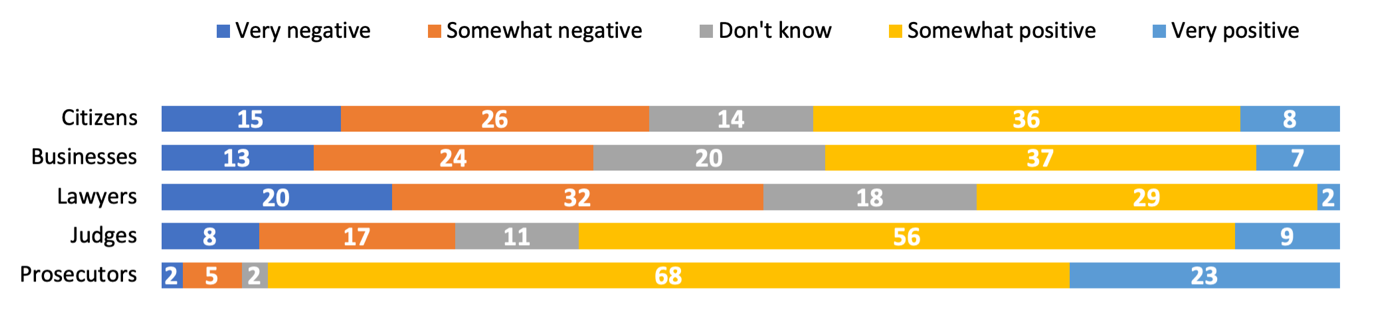

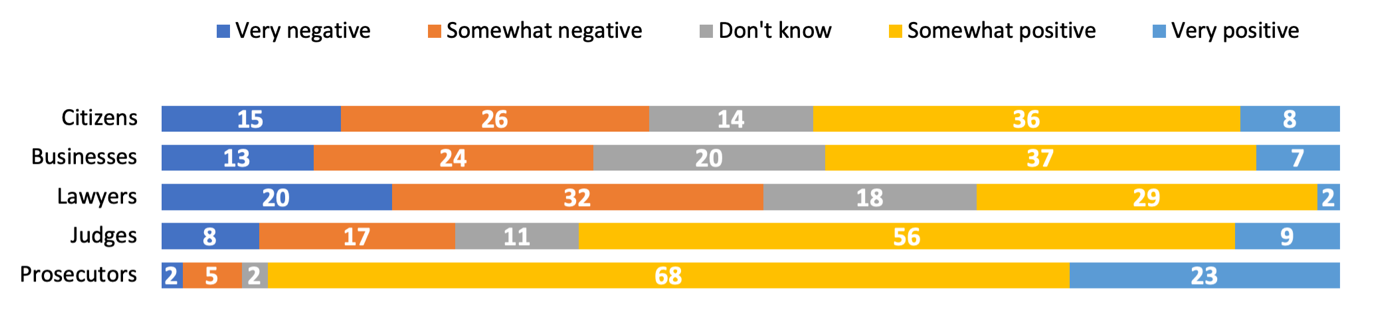

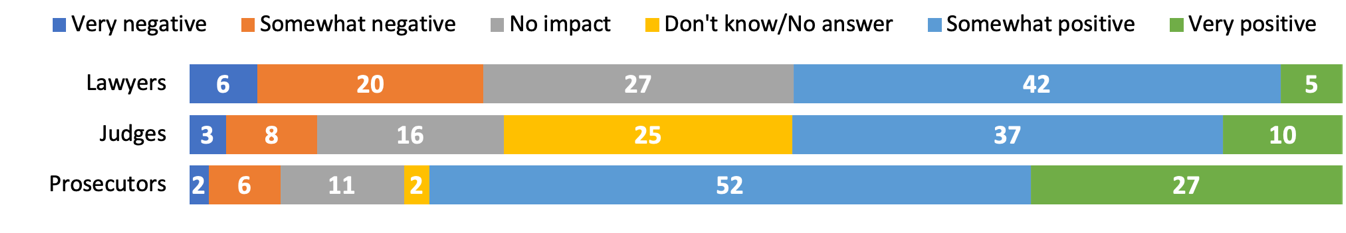

- According to the Regional Justice Survey, the highest

level of satisfaction with the efficiency of public prosecutors is

present among prosecutors themselves and judges, while lawyers are the

least satisfied. Court service users stand somewhere in

between. Nine out of ten prosecutors believe that their institution

efficiently performs designated tasks (91percent). Judges predominantly

agree with them, with two-thirds of those satisfied with the public

prosecution’s efficiency (65percent). The general public and businesses

have very similar views – 44percent of both populations positively

evaluate prosecution’s efficiency.

Figure 80: CITIZENS, BUSINESSES, LAWYERS, JUDGES AND PROSECUTORS:

GENERAL PERCEPTION OF PROSECUTION EFFICIENCY

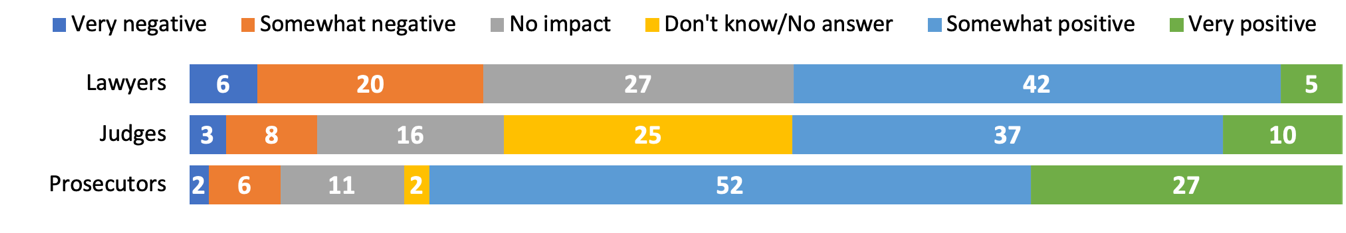

- Cooperation with other investigative bodies is recognized

by public prosecutors as the most important element that contributes to

the efficiency of prosecution service. As many as 79 percent of

prosecutors point out a positive impact of that collaboration, 11

percent do not consider it has any impact, while only 8 percent assess

it as negative. Judges and lawyers do not perceive cooperation between

prosecutors and other investigative bodies as relevant for the

efficiency of prosecution service.

Figure 81:LAWYERS, JUDGES AND PROSECUTORS: IMPACT OF COOPERATION

BETWEEN PUBLIC PROSECUTION AND OTHER INVESTIGATIVE BODIES

- Experience with prosecution makes citizens’ perception of

their efficiency more negative. 44 percent of citizens without

experience with public prosecutors have a positive opinion of their

efficiency, while only 37 percent of those with experience have the same

opinion. Unlike citizens, business representatives with personal

experience have at least a somewhat more positive view of the efficiency

of all public prosecutors.

- The majority of public prosecutors agreed that measures

for improving of efficiency of their work are increased the number of

prosecutors, investigators, and other staff, but also improvement of

infrastructure and cooperation with investigative bodies.

Prosecutors are almost completely uniform in the opinion that a larger

number of employees in the prosecution’s administration would primarily

lead to the higher efficiency of their office (97percent). Most of them

also underline an increase in the number of prosecutors themselves

(88percent), improved infrastructure (86percent) and better cooperation

with Police (84percent).

Impact

of the Covid-19 Pandemic on PPOs Efficiency in 2020 ↩︎

- The preliminary assessment of the impact of the pandemic

on the efficiency of PPOs indicates that there were no immediate effects

on Serbian PPOs, however, such impacts undoubtedly did occur and will

reveal themselves in the upcoming years. The declared state of

emergency from mid-March to mid-May 2020 halted prosecution proceedings

that were not deemed urgent and caused caseloads

and dispositions to decline. The overall clearance rates in 2020

remained favorable primarily due to the falling number of incoming

cases.

- The pandemic also forced changes in some of the

prosecutors’ work processes which may have affected both the quality and

efficiency of their work. For instance, some hearings had to be

held online, such as for violation of self-isolation measures. As of

December 2021, it was still hard to predict the extent of additional

congestion that would arise after the pandemic ends (or at least is

under greater control). They may be many proceedings ‘stuck’ in the

system in the meanwhile, and some new cases may appear as a direct

influence of the pandemic.

Recommendations and Next

Steps ↩︎

Recommendation 1: Improve and extend prosecutors’ use of

automatic CMS.

Automatic CMS for PPOs should be fully developed and rolled out,

including a detailed, flexible reporting module.

The new CMS (SAPO II) should allow the generation and use of these

recommended features:

- Perform gap analysis to identify which data, reports, alerts, and

searches will be needed for sole reliance on the CMS. (SPC, RPPO –

short-term)

- Specify which reports should be automatically and regularly

produced by CMS, aligned with internal and external reporting needs.

(SPC, RPPO – short-term)

- Specify which alerting mechanisms in the CMS would facilitate

case processing and enable prosecutors to manage their workload more

efficiently. (SPC, RPPO – short-term)

- Amend bylaws and rules accordingly. (SPC, RPPO –

medium-term)

- Migrate all existing data to the system. When necessary, enter

legacy data manually through simplified forms. Transfer all relevant

hard copy data to the digital system. (MOJ, RPPO, SPC, and PPOs –

medium-term)

- Eliminate paper registries in PPOs. (SPC, RPPO –

long-term)

Recommendation 2: Establish specialized investigation

departments.

The specialized investigation department established in the First

Basic PPO in Belgrade has been beneficial, and its implementation in

other Basic PPOs and in Higher PPOs is worth exploring.

- Conduct a study in the First Basic PPO in Belgrade to determine

what aspects of that department should be established in other Basic and

Higher PPOs, for what case types, and the resources necessary to do so.

(RPPO, SPC – short-term)

- Provide the necessary resources for the new departments to

operate. (SPC, RPPO, MOJ – medium-term)

Recommendation 3: Improve monitoring of caseloads and

performance.

Regularly monitor prosecutors’ tasks to assess their caseload and

performance. This addresses prosecutors’ concerns that their work on

cases that significantly increase their workload is not adequately taken

into account during the distribution of cases and their performance

assessments.

- Identify these tasks and analyze their impact on the performance

of PPOs. (SPC, RPPO – short- term)

- Unify data entry and tracking of ‘KTR’ cases among PPOs and avoid

double-registering cases (RPPO

- – short-term)

- Quantify how much work prosecutors are investing in ‘KTR’ cases.

(SPC, RPPO – short-term)

- Consider using CMS for the classification of ‘KTR’ cases in order

to evaluate their impact on performance. (RPPO, SPC –

medium-term)

- Enter and manage data on ‘KTR’ cases in a way that will continue

to identify them once a prosecutor has begun a formal investigation of

the matter and moved the case to a different registry. (RPPO, SPC –

medium-term)

- Track time to disposition in all case types. (RPPO, SPC –

medium-term)

Recommendation 4: Improve processing of cases about unknown

perpetrators.

- Regularly archive ‘KTN’ cases so they do not burden the system

once their statutes of limitation expire. (RPPO – medium-term)

Recommendation 5: Develop a backlog reduction plan to reduce

the significant number of carried-over cases, particularly cases that

have been pending for over two years.

The judiciary should be included in most if not all of the following

as needed. However, there may be policies or programs that prosecutors

can pursue internally to monitor the timeliness and reduce backlogs in

PPOs.

- Establish a permanent working group to draft and monitor the

implementation of the backlog reduction plan. Membership of the group

may change over time, but its function should not since backlogs are a

permanent threat to the efficiency and quality of all prosecutorial

systems. (RPPO – short-term)

- Develop and update a list of aging cases being handled by each

PPO. The lists would contribute to the detailed design of a CMS and

backlog reduction plans for all PPOs. These lists should be updated at

least every six months. (RPPO short-term) Publicize results. (RPPO –

medium-term)

Recommendation 6: Identify, disseminate, and incentivize

sharing of good practices.

Conduct a detailed study of the investigation, case handling,

management, and administrative practices of the most efficient PPOs in

each size category. The study would identify processes or policies that

could help other PPOs improve their case disposition times and numbers

and reduce the age and number of cases carried over from one year to the

next.

- Prepare a report detailing the most efficient practices and the

preconditions for putting them into practice in other PPOs. (RPPO, SPC –

short-term)

- Prepare relevant Rules and ‘bench books’ to record the steps

necessary to implement the recommended practices. (SPC, RPPO –

short-term)

- Roll out efficient practices to lower-performing PPOs through

peer exchange programs, workshops, JA training, etc. (SPC, RPPO, JA –

medium-term)

- Develop incentives for the highest performing and most improved

prosecution offices. This could be modeled on the existing award program

for the best-performing courts. (RPPO, SPC – medium- term)

Recommendation 7: Allocate prosecutorial resources based on

demand for services rather than population to equalize the number of

cases per prosecutor (RPPO, SPC – medium-term)

Calculations

Calculations